Executed March 8, 2012 at 11:26 a.m. by Lethal Injection in Arizona

8th murderer executed in U.S. in 2012

1285th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

2nd murderer executed in Arizona in 2011

30th murderer executed in Arizona since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(8) |

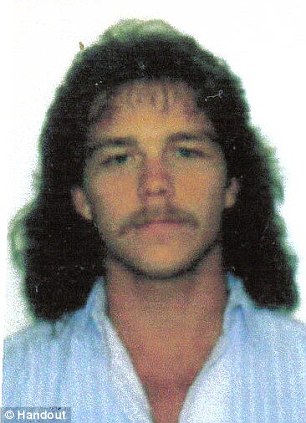

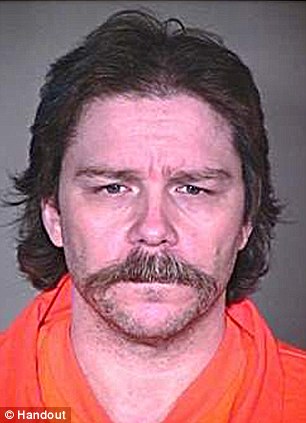

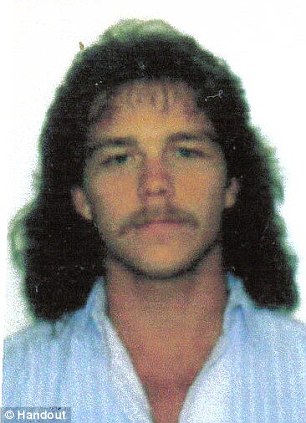

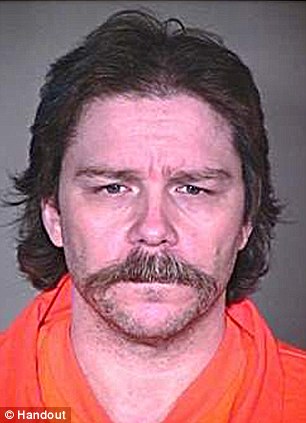

Robert Charles Towery W / M / 27 - 47 |

Mark Jones W / M / 69 |

In exchange for his testimony, accomplice Barker pled guilty to second degree murder, served only 10 years in prison and was released.

Citations:

State v. Towery, 186 Ariz. 168, 920 P.2d 29 (Ariz. 1996). (Direct Appeal)

Towery v. Schriro, 622 F.3d 1237 (9th Cir. 2010). (Habeas)

Final Words:

Towery apologized to his family and to the victims. He talked about bad choices he had made. Then he said, as he appeared to be crying, "I love my family. Potato, potato, potato." His reference to potatoes was a message to a nephew who witnessed the execution, and referred to the sound made by a Harley-Davidson motorcycle. Towery's attorney, Dale Baich, said it was Towery's way of telling his nephew that everything was OK.

Final / Special Meal:

Porterhouse steak, Sauteed mushrooms, Baked potato with butter and sour cream, Steamed asparagus, Clam chowder, Pepsi, Milk, and Apple pie with vanilla ice cream.

Internet Sources:

Arizona Department of Corrections

INMATE #051550 TOWERY ROBERT, C

Date of Birth July 20, 1964

Executed March 8, 2012

Defendant: Caucasian

On September 4, 1991, Towery and Randy Barker went to the home of Mark Jones to rob him. Jones knew Towery, and let Towery and Barker into the home. Towery pulled a pistol on Jones, and Barker handcuffed him. Towery took valuables from the house and loaded them into Jones' vehicle. Barker took Jones to the bedroom. Towery told Jones that he was going to give him injections with something that would make him sleep. Towery then injected Jones with battery acid. Jones was not struggling because he trusted Towery. Towery then sought to strangle Jones to death. When the first try failed, he tried again and succeeded. Towery and Barker then left in Jones' car, unloaded Jones' property at their home, and left the car in a nearby parking lot. On September 5, 1991, Jones' body was discovered. On September 12, 1993, Jones' car was recovered. As a result of a tip given to the silent witness program, Towery and Barker were later arrested. Some of Jones' property was recovered from Towery's and Barker's homes.

PROCEEDINGS

Presiding Judge:Hon. Cheryl K. Hendrix

Prosecutor:John Ditsworth

Defense Counsel:James Hazel, Jr.

Start of Trial:August 3, 1992

Verdict:August 14, 1992

Sentencing:November 20, 1992

Aggravating Circumstances:

Prior convictions punishable by life imprisonment

Prior convictions for crimes of violence

Pecuniary gain

Especially heinous, cruel or depraved

PUBLISHED OPINIONS

State v. Towery, 186 Ariz. 168, 920 P.2d 290 (1996).

State v. Towery, et. al., 204 Ariz. 386, 64 P.3d 828 (2003).

Inmate: TOWERY ROBERT C

DOC#: 051550

DOB: 07/20/1964

Gender: Male

Height 70"

Weight: 165

Hair Color: Brown

Eye Color: Blue

Ethnic: Caucasian

Sentence: DEATH

Admission: 12-10-1992

Conviction Imposed: MURDER 1ST DEGREE

County: MARICOPA

Case#: 9192648

Date of Offense: 09-04-91

Prior Commitment: Armed Robbery, Kidnapping (4 Counts), Maricopsa County LIFE 1991

Robert C. Towery

Date of Birth: July 20, 1964.

On Sept. 4, 1991, Towery and Randy Barker went to the home of Mark Jones to rob him. Jones knew Towery and let Towery and Barker into the home. Towery pulled a pistol on Jones, and Barker handcuffed him. Towery took valuables from the house and loaded them into Jones' vehicle. Barker took Jones to the bedroom. Towery told Jones that he was going to give him injections with something that would make him sleep. Towery then injected Jones with battery acid. Jones was not struggling because he trusted Towery. Towery then sought to strangle Jones to death. When the first try failed, he tried again and succeeded. Towery and Barker then left in Jones's car, unloaded Jones's property at their home, and left the car in a nearby parking lot. On Sept. 5, 1991, Jones's body was discovered. On Sept. 12, 1993, Jones's car was recovered. As a result of tip given to the Silent Witness program, Towery and Barker were later arrested. Some of Jones's property was recovered from Towery's and Barker's home.

Trial

Convicted: Aug. 14, 1992.Sentenced to death: Nov. 20, 1992.

Mitigating Circumstances None sufficient to call for leniency

Source: "Profiles of Arizona Death Row Inmates," Arizona Attorney General's Office.

"Inmate facing execution loses appeals," by Michael Kiefer. (Mar. 07, 2012)

Robert Towery spent the first half of his life not thinking and the last half of his life thinking about the thoughtless act that put him on death row.

Thursday morning, he will be strapped to a table at the Arizona State Prison Complex-Florence and executed for killing a Paradise Valley man during a 1991 armed robbery.

He was 27 that year, an ex-con with a raging methamphetamine addiction, a man — he told his attorneys — who just reacted to stimuli without reflecting on what he was doing.

“I can’t make sense of it,” he said at his clemency hearing last week. “It was just one mistake after another. It ended with taking a man’s life. I wish I could change it, but I can’t.”

He did time for running a chop shop. He robbed a restaurant at gunpoint and then planned to rob Mark Jones, an acquaintance who had been kind enough to lend him money.

He knew he didn’t have to kill Jones, he told the state clemency board. He just did. He put a plastic zip tie around Jones’ neck and pulled it tight until he thought Jones was dead. And when he realized Jones was still breathing, he did it again.

At his trial, prosecutors claimed Towery tried to inject Jones with acid taken from a car battery with a syringe. That’s what Towery’s accomplice told investigators, though the theory was not proved at trial and has since been questioned.

Towery admitted at his clemency hearing that he killed Jones, but he didn’t remember a syringe.

Over the past 20 years, Towery has thought about the murder and spoken about it to best-selling novelist Jodi Picoult, who interviewed him for her 2007 novel “Change of Heart.”

“We have kept up a pen-pal relationship, where he asks me about my kids or talks to me about the plots of ‘Lost’ and ‘Grey’s Anatomy,’ ” Picoult wrote on her website.

“He is an accomplished artist who makes his paints from the pigments of shells of Skittles and M&Ms, or from diluting coffee and ink on the pages of magazines. He’s taught me how you make a knife in prison, or a stinger to heat up your soup. He’s a very nice guy – except for the fact that he was convicted in 1991 of armed robbery, during which he told the victim that he was going to sedate him and instead injected the man with battery acid and killed him.”

According to his clemency petition, Towery started drinking at age 6. That same year, he was raped by a male neighbor and wounded by a stray bullet.

When he was 8, the petition said, his mother tied him up and made him lie on the floor of the car. When he was 12, it said, his mother made him steal to help support the family.

At Towery’s clemency hearing, his two sisters told of the beatings they suffered at the hands of their mother, how she would hang Towery’s bedsheets outside the house so his friends could see he was a bed-wetter.

When he was 15, his mother threw him out of the house and had him arrested when he sneaked in to take a shower before school.

By 17, he was using methamphetamine, barbiturates, marijuana, angel dust, cocaine and LSD.

A doctor at his clemency hearing said Towery was taking enough meth on a daily basis to kill a normal person.

At the hearing, however, a clemency-board member cut to the point: They hear similar stories in nearly every clemency hearing. She noted that Towery seemed to be a nice person.

“But the issue is the crime,” she said. “Why should we look at you as any different from anyone else?”

The crime took place on Sept. 4, 1991. Towery was running his own mechanic business: One of his clients was Jones, 68, a Paradise Valley philanthropist with a transplanted heart who had lent him money and offered business advice.

“He was actually quite nice to me,” Towery said.

Nonetheless, Towery and an accomplice, Randy Barker, planned the robbery and the possible killing of Jones.

They took a cab to Jones’ house and told Jones they needed to use a phone because their car broke down. Then, they held Jones at gunpoint and ransacked the house. According to the court record and testimony at Towery’s clemency hearing, they forced Jones into a bedroom.

There, Barker claimed, Towery injected Jones with battery acid, telling him it would make him sleep. Barker claimed that Jones pretended to sleep and that Towery strangled him.

Barker was given a 10-year prison sentence in exchange for his testimony against Towery and was released from prison in 2001.

"Robert Towery Executed By Lethal Injection," by Paul Rubin. (Thu Mar. 8 2012 at 1:12 PM)

Robert Towery, a 47-year-old Mesa man who spent the last two decades of his life on death, was executed late this morning at the state prison in Florence. Towery's last-minute appeals didn't pass muster, and prison officials injected the inmate with the poisonous chemicals that killed him.

He was charged in the brutal 1991 killing of 69-year-old philanthropist Mark Jones, a Paradise Valley man known for providing dozens of University of Arizona students with scholarship funds. Jones as we noted in a Valley Fever blog post yesterday, invited Towery--an acquaintance--and another man into his residence. The pair were there to rob Jones, and according to Towery's accomplice, Towery also had designs on killing him.

Jones died of manual strangulation with a plastic tie, and Towery's cohort, Randy Allen Barker, later told police (and a Maricopa County jury) that Towery had injected the victim with battery acid. Prosecutors never could definitively prove the latter, but they had more than enough evidence to win a conviction on first-degree murder and other charges.

In return for his testimony against Towery, prosecutors cut co-conspirator Barker a pretty sweet deal. Barker was released from prison in 2001 after serving about ten years. As we wrote yesterday, Robert "Chewie" Towery, a violent criminal with a yen for meth, ad pulled himself together behind bars in recent years, and reconnected with family members, including his college-age son. We corresponded with Towery in recent months, and he invited us to attend his execution, which he fully expected would occur as scheduled.

We declined, having no desire to watch the government stick a needle into a condemned man behind a glass retaining wall. Our old colleague Mike Kiefer of the Arizona Republic reported that Towery's last meal consisted of a porterhouse steak, baked potato with sour cream, asparagus, mushrooms, milk, Pepsi and apple pie a la mode.

If we still have a death penalty in place at this late date, and it is supposed to be reserved for the worst of the worst, Robert Towery had it coming to him. He may not have died as the worst person around, but the vile and violent acts he perpetrated upon Mr. Jones put him in that category when it counted--when he chose to murder.

But, just saying, locking Towery up, throwing away the key, and letting him exist in that netherworld known as the Arizona State Prison until he died would have been just fine with us.

"Arizona kills man for '91 murder in 2nd execution in 9 days," by Michael Kiefer. (Mar 8, 2012 06:42 PM)

Arizona death-row inmate Robert Towery was executed by lethal injection Thursday for the 1991 murder of a Paradise Valley philanthropist during a robbery.

Towery, 38, was pronounced dead at 11:26 a.m., nine minutes after the lethal-injection procedure began at the Arizona State Prison Complex-Florence.

Towery's execution came just eight days after Arizona executed another inmate, Robert Moormann, for killing and dismembering his mother 28 years ago.

Wednesday night, Towery was served a last meal of porterhouse steak, baked potato with sour cream, asparagus, mushrooms, clam chowder, milk, Pepsi and apple pie a la mode.

Towery met with his attorneys Thursday before the execution began. The execution was scheduled to start at 10a.m., but his attorney's visit ran long and the executioner discovered he had to insert a catheter in the femoral artery, suggesting that they could not raise a vein in his arm.

Witnesses were not led into Housing Unit 9, where executions are carried out, until a few minutes after 11 a.m.

The execution began at 11:17 a.m. Towery looked to his family and attorneys. In his last words, he apologized to his family and to the victims. He talked about bad choices he had made. Then he said, as he appeared to be crying, "I love my family. Potato, potato, potato."

His reference to potatoes was a message to a nephew who witnessed the execution, and referred to the sound made by a Harley-Davidson motorcycle. Towery's attorney, Dale Baich, said it was Towery's way of telling his nephew that everything was OK.

But Baich said there were other messages buried in other of Towery's last words -- which puzzled journalists witnessing the execution -- including a suggestion that Towery had asked to call his attorney before his execution and was not allowed.

Once the injection was administered, he took several hard breaths, one witness said, and then slipped into unconsciousness.

Towery was sentenced to death for killing Mark Jones during an armed robbery at Jones' home.

Towery was Jones' mechanic, and Jones had even lent him money on two occasions. On Sept. 4, 1991, Towery and an accomplice went to his house, pretending they needed to use the phone to make a call because their car broke down. They held Jones, 68, at gunpoint and ransacked his house. Then Towery strangled him with zip ties. The accomplice testified that Towery also injected Jones with battery acid from a syringe. Then the two made off in one of Jones' cars with a television set, cash and credit cards.

In exchange for his testimony, the accomplice served only 10 years in prison and was released.

At Towery's clemency hearing last week, Towery claimed no memory of any syringe and said he could not understand why he took Jones' life.

His attorneys and doctors described at that hearing Towery's horrific childhood and his severe addiction to methamphetamine. The clemency board did not feel that those circumstances outweighed the seriousness of the crime, and it refused to grant him a commutation or a reprieve.

Late Wednesday, the Arizona and U.S. Supreme Courts denied Towery's last-minute requests for a stay of execution.

Convicted murderer Robert Towery was executed Thursday morning for the 1991 murder of Paradise Valley philanthropist Mark Jones.

Beginning Feb. 2, the day he was taken from his regular cell at the Arizona State Prison Complex-Eyman in Florence and put on "Death Watch," Towery chronicled his life for his attorneys. There, he was housed with fellow Death Row inmate Robert Moormann, who was executed Feb. 29.

On March 7, his last night on Earth, Towery was taken a few miles down the road to "Housing Unit 9," in the main prison, where Arizona carries out executions by lethal injection. He made his last diary entry the next morning.

These are excerpts from that diary - Towery's words, his descriptions of the tedium, the rituals, the security, the indignities and the humanity, precisely as he wrote it - right up to the morning of his execution.

Feb. 2

And so it begins... First let me apologize for the messiness of these first letters as I was not allowed my reading glasses as they had a crack in them and I was holding them lens in with tape. So I can't see. [...] Furthermore, I was not given my watch, so for the most part, all times will be best guesses.

6 a.m. They came to my cell, stripped me out and then took me to the shift commander's office where I waited for about 20 min for everyone to show up. [...]

The unit warden began to read the warrant only to discover they were missing pages, So I offered my copy and they sent a (correctional officer) to my cell who brought back the box containing my copy. In the meantime, the unit warden went over the changes in my confinement. How I could have access to indigent supplies, and could have one box of legal work/personal papers, and one religious box. For everything else I would have to put in a written request.

[...]

At noon [...] they took me back to medical where the nurse went over my daily meds with me and how the meds, which have been coming to me in monthly supply packs for fifteen years or so are somehow now so dangerous that the nurse has to bring them to me every morning on a "watch swallow basis."

[...]

A few notes about my cell. They have a TV pushed up in front of the cell, so looking through the holes (in the security screen) is difficult at best, and nauseating/vertigo inducing to the point where I really just want to listen to it, but there is a problem there. The earbud extension they stretch through the hole barely reaches to the table, a good five or six feet short of the bunk.

[...]

Feb. 3

6:30 a.m. They asked me if I wanted rec or a shower. I asked for a shower. They stripped me out with a female officer present. (Now, personally, I'm not the shy type, but having a female officer on death watch is just one more humiliation.) Anywho, as I came out the nurse was there to take my vitals. [...] they also took my temperature and pulse. Don't know why they were.

So I take a shower with the generic soap and shampoo they provide. I asked about conditioner, there is none. [...] so after my shower I asked for a palm brush. No. Asked for a comb. There isn't one. [...] So I told them I could just use the clippers and shave my head. No big deal to me. If I can't take care of my hair properly, I'd rather shave it. I usually do for the summer. [...]

Approx 9:00 a.m. or so, psych dr came in and asked me if I was alright. I told him I was all good and sent him on his way.

Approx 11:00 a.m., assistant deputy warden woke me up with "I heard you wanted to shave your head." (I guess the COs made it sound like I was flipping out when I was completely calm. Long hair, bald, I'm fine with either.)

[...]

The feeling of complete helplessness and hopelessness grows by the hour because of the way all of this is done. Every time you want to blow your nose or go to the bathroom you have to ask for toilet paper. [...] 3:00 p.m. (approx) the psych nurse just came with the same questions. Are you suicidal? Homicidal? Anything you want to talk about?

[...]

You are allowed one book. Okay, I got Jodi's novel (Towery was pen pals with the novelist Jodi Picoult), which I will read as soon as I get my glasses.

[...]

No way I can work out without my knee braces, shoes, ankle sleeves, all the things my busted old body needs. Oh, and motivation. Don't have that either to be honest.

[...]

Feb. 12

5:00 a.m. Oh my gosh! Now a nurse is in here. Bob [Moormann] was feeling a bit out of it (his blood sugar), so she's come in to check. He is speaking in ultra-hushed tones, and she is practically yelling, "What? I can't hear you Mr. Moormann, I'm really hard of hearing."

[...]

Look at Bob. As I was saying on the phone, Bob is one of the meekest, polite and quiet man I have ever met. I truly believe they are committing a crime against nature if they execute him. He doesn't get this. Sure, he knows right from wrong. He knows they are going to kill him. He knows he committed a horrific crime. Sure. But he knows these things as a child does. I'm not a doctor, but I can tell you from knowing Bob for nearly 20 years now, he doesn't really get it. He is guilty, no doubt, but there is no way he is culpable in it. What I mean is, he should have been in a hospital from the very beginning. His stepmother and what she did to him broke him in a way that made him a man-child. I liken him to Lenny in the old book Of Mice and Men.

[...]

6:33 a.m. My weight, 221, officially 10 lbs lost since coming here on the 2nd. My B.P. was 138/80. I have my phone call with [blacked out] at 10:15 and a visit at 11:00 a.m. Woo hoo!!! Today is going to be a great day!!

[...]

Feb. 13

Oh! One more observation, and for me, it's a good one!! I have not seen a single roach, water bug, scorpion, stink beetle or spider. Woo-hoo!! Over on the other side I lived next to the rec pen and I went on Safari daily!

[...]

Feb. 15

Okay, this is funny. Exactly who is watching whom? I'm sitting here watching the news, and happen to glance up to see both COs with their chins on their chests and their eyes closed. Good for them! Second to the stress I feel, my family feels and of course the stress you'll feel, I'm sure this has to be stressful to them too. So a moment's relaxation is well earned. I also enjoy the irony.

[...]

Feb. 16

8:50 a.m. They just called an ICS. Something is wrong with Bob. He had told the nurse this morning that he had problems sleeping last night, and then he was throwing up and barely responsive. They took him to medical in a wheelchair, and the officer went in and cleaned up his cell.

10:14 a.m. It just came across the radio. Bob is leaving the unit to go to the hospital.

[...]

Feb. 18

4:16 p.m. They just brought Bob back in a wheelchair!! He's been up at medical the last two hours, but I don't have any details yet. What amazes me is that he can barely walk or respond, and still they make him come to the front of his cell after they close the door to remove his restraints.

[...]

Feb. 21

6:40 p.m. Bob called and asked me what ya'll had to say from today's [federal court] hearing. I let him know we figured about right as to Judge [Neil] Wake's position. But I told him that if Wake rules tonight or tomorrow against us, that we will appeal to the 9th [U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals]. He asked me, "Then who will give a stay?" I told him it would be up to the 9th. He said, "Yeah, but what judge will give me a stay?" and I told him we would have a 3 judge panel most likely and they would rule on the injunction. He said "Okay, you know I don't understand this legal stuff. I'm sorry if I bothered you." I told him it was no bother and he could call me any time. He's so lost!

[...]

Feb. 27

6:09 p.m. WORST NIGHT YET! [...] They just did shift change and we have a female on watch! Which I think is completely inappropriate! I don't have an issue with women working the prison, or anywhere, generally. But, in a situation like this when you can't go to the bathroom without someone being 10 feet away staring at you, it's just not right.

[...]

Feb. 28

Bob is gone. May God forgive them.

March 1

6:52 a.m. The Sgt. asked me what happened with Bob, and of course I told him I wasn't here when they took Bob out. He said that apparently Bob started freaking out and made himself sick. I think his system just wasn't used to the food and two pints of ice cream.

[...]

March 2

The [clemency] hearing went as I expected. [...] My sisters were amazing, but the board had no intention of granting clemency. [...]

The staff was visibly upset by it. They remained professional, but they were clearly affected. They are human after all.

[...]

March 7

Hey now! I hope this, my last log finds you doing great! As for myself? Well, things are about as I imagined. They showed up at about 10:20 p.m. to strip me out. They did the whole naked dance and the squat and cough. Then they gave me a pair of boxers and a pair of deck shoes. I was grabbed on both sides, firmly, but not roughly. I was taken to the boss chair, and from there I was taken to a day cell, given a pair of socks, t-shirt, and a pair of pants with A BUTTON + ZIPPER!! Woo-hoo!!

Anywho, I was then put in a belly chain, shackles and then led out to a waiting van. Again, I went nowhere without hands on me. Even when they were putting the cuffs on, someone was holding my arm. We rode over here. Nice ride, and they kept up the small talk. It was cool watching one of the COs with what I assume was an iPhone.

Once arriving here, they ushered me in. All the while they are telling me they will be respectful and ask that I be. The warden warned me about my final words. I've been told that I should think about my statement and that he will (or someone will) rehearse it with me in the morning.

[...]

One more thing: there are four officers watching me, carrying on conversations and two are female. AND I'M SUPPOSED TO SLEEP?!

The two female officers disappeared around the corner, so I took the opportunity to urinate. But they came right back. The male officer said I was using the restroom, and the response was, "I work in an all male prison." True, but still, there can be respect! Then I had to ask for some soap and a towel. I was given a bar of soap and one paper towel. And had to give them back!!

[...]

March 8

7:00 a.m. Good morning! Well, I actually slept well. I woke up about 5:00 a.m. I was given a doughnut and a fairly large container. [...] The orange juice was great! (First orange juice I've had in I don't know how long!) The doughnut was prison issue. Enough said.

I just finished my visit with Deacon Ed and receiving communion. Now I'm just waiting for y'all, at which point I'm going to give you my legal work and my Bible. Please give my Bible to [name blacked out].

As this is my last entry, I just want to say thank you. Thank you all for the kindness. Please give everyone my best and know that I will carry y'all on my lips to God.

My best wishes to you all. Take care. May God Bless!!

Sincerely, Robert Charles Towery.

"Robert Towery's Death Row Writings." (Wednesday, March 14, 2012)

Towrey was executed in Arizona last week. His Death Watch Diary is now available in a free Kindle edition from Amazon. This description is from Amazon:

For the last 35 days of his life, Robert was placed on “Death Watch” where his every move was recorded and chronicled by prison officials.

Robert also kept a diary which he gave or mailed to his attorneys as installments. He detailed the ironies and absurdities of life in prison. He reveled in simple pleasures, such as a good meal or a sports event on television. He longed for human contact from his last visitors, and he touchingly tried to comfort his pod-mate, who doesn’t really understand that he was going to his death.

Beginning Feb. 2, the day he was taken from his regular cell at the Arizona State Prison Complex-Eyman in Florence and put on "Death Watch," Towery chronicled his life for his attorneys. There, he was housed with fellow Death Row inmate Robert Moormann, who was executed Feb. 29.

On March 7, his last night on Earth, Towery was taken a few miles down the road to "Housing Unit 9," in the main prison, where Arizona carries out executions by lethal injection. He made his last diary entry the next morning.

These are excerpts from that diary - Towery's words, his descriptions of the tedium, the rituals, the security, the indignities and the humanity, precisely as he wrote it - right up to the morning of his execution.

In the weeks before he was executed for strangling a man to death, Arizona inmate Robert Towery kept a diary.

His writings began Feb. 2, when he was transferred to a “death watch” cell in state prison, and ended Thursday, shortly before he was put to death by lethal injection at 11:26 a.m. The Associated Press described the execution -- and the events leading up to it.

Towery, 47, had been convicted of killing Mark Jones during a robbery in 1991; he was the second inmate put to death in Arizona in a two-week period.

Towery’s entries, some of which the Arizona Republic published, are striking in their banality. He asked prison officials for conditioner, and there was none. A brush or comb? Nope. He couldn’t find the motivation to work out, either.

Towery looked for bits of humor, such as when he saw two correctional officers doze off. “Exactly who is watching whom?” he wrote. He joked about his new living quarters being cleaner than his old ones. “I have not seen a single roach, water bug, scorpion, stink beetle or spider. Woo-hoo!!”

That evening, Towery and Barker drove in Barker’s car to a Denny’s Restaurant and from there took a taxi to be dropped off in Mark Jones’s neighborhood. They knocked on Mark’s door, and Towery asked if they could use his telephone because their vehicle had broken down. Towery said, “Do you remember me? I’m from R and D Automotive.” Mark Jones had been introduced to Towery on a prior occasion when Towery sought counseling about his new business enterprise. Mark invited them in and showed them the telephone. After the two were let in, Barker pretended to make a telephone call, while Towery pulled a gun out of his briefcase. The briefcase also contained gloves, plastic tie wraps, handcuffs and a large veterinary syringe apparently filled with battery acid. Towery told Mark that they were robbing him, both men put gloves on and Barker handcuffed Mark.

Over the course of about two hours, Barker kept watch on Mark while Towery rummaged through the house, took Mark's car keys and collected about $1,200 in cash from his wallet and drawers in the home. Towery loaded Mark’s Lincoln with jewelry, electronics, cameras and other items. Towery and Barker then led Mark to the master bedroom at gunpoint, uncuffing him while he used the bathroom along the way. They asked him whether he expected anyone soon and Mark said no. Towery asked Jones whether he preferred to be tied up or to be injected with a drug that would put him to sleep. Mark chose the latter option and was laid face down on the bed. At his request, Mark's shoes were removed to make him more comfortable.

Towery then tried several times to inject Jones with a large veterinary syringe that Barker believed contained battery acid but pushed the needle all the way through the vein. Believing Jones was pretending to have fallen asleep, Towery created a noose using a set of tie wraps from his briefcase and slipped it over Mark's head and began to strangle him. Mark did not struggle, but made choking and gagging sounds. After cutting and removing the noose, Towery determined that Mark was not yet dead, made another noose and repeated his previous action. Towery and Barker then loaded a large television into Mark's other car, a Dodge convertible. While trying to start the Dodge, Barker set off its alarm. Barker and Towery jumped into the Lincoln and Towery drove to the Denny’s to get Barker’s car. Barker threw the syringe out the window into an oleander hedge along the way. They unloaded the goods at their house and removed the compact disk player from the car before they abandoned it in the parking lot of an apartment complex.

A security guard at the complex saw the men and later identified Towery in a photo lineup. Mark Jones’s body was discovered the next morning. Towery testified and offered an alibi. He said he dropped Barker off at the Denny’s and saw him get picked up by someone else. Towery then drove Barker’s car to meet Tina Collins at an adult book shop. Towery drove with Collins to another parking lot, where they talked for about two hours. Afterward, not finding Barker at their planned meeting spot, Towery drove home. Barker arrived at the house with Jones’s car and property, and Towery helped him unload the goods and dispose of the car. Towery also claimed that he bought the stolen items that the police found in his possession from Barker. Collins’ videotaped deposition was admitted to corroborate Towery’s story. She said they had first met a couple of weeks earlier and arranged to meet on September 4. She did not talk with Towery again until February 9, when she visited the prison at the suggestion of a friend of hers who happened to be visiting Towery’s cellmate.

Wikipedia: List of People executed in Arizona Since 1976

1 Donald Eugene Harding White 43 M 06-Apr-1992 Lethal gas Allen Gage, Robert Wise, and Martin Concannon

State v. Towery, 186 Ariz. 168, 920 P.2d 29 (Ariz. 1996). (Direct Appeal)

FELDMAN, Chief Justice.

On October 3, 1991, Robert Charles Towery ("Defendant") and Randy Allen Barker were charged in Maricopa County on six counts: first-degree murder, armed robbery, first-degree burglary, kidnapping, theft, and attempted theft. About six months before trial, the trial judge granted Defendant's motion to sever. Defendant's murder trial began on August 3, 1992. Eleven days later, the jury found him guilty of felony murder and all other counts. At the sentencing hearing, the trial judge sentenced Defendant to death for the murder and to concurrent prison terms of five to twenty-one years for the other counts.

This automatic appeal of the death sentence followed. Ariz. Const. art. 6, § 5(3); A.R.S. §§ 13-4031 and 13-4033(A).

STATEMENT OF FACTS

In exchange for a reduced charge of second-degree murder, Barker testified against Defendant and provided much of the State's evidence. Other witnesses corroborated some critical features of Barker's story and connected Defendant with the charged offenses. Nevertheless, the State's case rested on Barker's testimony. His version of the facts follows.

A. Barker's story

Defendant, Barker, and John Meacham rented a three-bedroom house in Scottsdale, Arizona. Defendant occupied one bedroom with his girlfriend, Diane Weber, and her infant daughter. Barker occupied another bedroom with his then- girlfriend, Monique Rousseau. For several weeks, Defendant and Barker had discussed "pulling off a robbery" of one of two possible victims known to Defendant. On September 4, 1991, they decided to rob Mark Jones at his home.

That evening they drove in Barker's car to a Denny's Restaurant where they called a taxi. The taxi dropped them off near Jones' home. They walked to the house and knocked on the door. When Jones answered, Defendant said his car had broken down and asked if he and Barker could come in to use the telephone. Defendant asked Jones, "Do you remember me? I'm from R and D Automotive." Jones had been introduced to Defendant on a prior occasion when Defendant sought counseling about his new business enterprise. Jones invited them in and showed them the telephone. While Barker faked a telephone call, Defendant opened his briefcase and pulled out a gun. The briefcase also contained gloves, plastic tie wraps, handcuffs, and a large veterinary syringe apparently filled with battery acid. After Defendant and Barker put on gloves, Barker handcuffed Jones. Defendant rummaged through the house, took Jones' car keys, and loaded Jones' Lincoln with a television, photocopy machine, cameras, jewelry, and other items. Defendant removed Jones' wallet from his back pocket and took about $200 and credit cards. They also took $1,000 from a desk drawer.

Before leaving, Defendant and Barker took Jones to the master bedroom at gunpoint, uncuffing him while he used the bathroom along the way. They asked him whether he was expecting anyone soon, and Jones said no. According to Barker, Defendant offered Jones "about two choices in the matter of how we could leave him. One was ... [to] tie him up, ... the other was to introduce a drug into him to make him sleep instead of being tied up." Jones chose to be put to sleep and was laid face down on the bed with his hands bound behind his back. Contrary to his statement to Jones, Defendant apparently believed the injected substance would kill Jones.

At his request, Jones' shoes were removed to make him more comfortable. Defendant made several attempts to inject the contents of the syringe into Jones' arm, pushing the needle all the way through a vein. The drug having no effect, Jones pretended to sleep by snoring. Determined to kill Jones, Defendant made a noose out of plastic tie wraps from his briefcase, slipped it over Jones' head, and pulled tightly on its end to strangle Jones. Jones did not struggle but made choking and gagging sounds. Defendant then cut and removed the tie-wrap noose from Jones' neck. Believing Jones was not yet dead, Defendant made another noose "like the first one ... popped [it] over the head, and pulled tight with a 'zip' sound," explained Barker.

The two men then loaded a large television into Jones' other car, a Dodge convertible. While trying to start the Dodge, Barker set off its alarm. Barker jumped into the Lincoln and the two men drove away with Defendant at the wheel. Barker allegedly threw the empty syringe out the window into an oleander hedge [FN1] as they drove back to Denny's to get Barker's car. They returned to their home, unloaded the goods, putting some into Meacham's bedroom, and removed a compact disk player from the Lincoln's dash. Defendant then drove the Lincoln to the parking lot of an apartment complex while Barker followed in his car. They parked the Lincoln there and returned home. A security guard at the complex saw the men and later identified Defendant in a photo lineup.

FN1. Police later searched the area for the syringe but never found it.

The next morning, Meacham returned from work to discover in his bedroom items he had not seen before. Defendant, Barker, and Diane were also in the house. Meanwhile, two employees of the golf club that Jones frequented had looked for Jones and found his body about mid-morning that day.

B. Defendant's version

Defendant testified and offered an alibi. According to Defendant, on the night of the robbery he had driven Barker to Denny's in Barker's car. He had a soda until Barker's taxi arrived, then drove to Zorba's, an adult book store, where he had arranged to meet Tina Collins. While waiting, Defendant went inside to buy a book and returned to his car. Tina arrived at Zorba's about fifteen minutes after Defendant. They then drove and parked near Defendant's home, talking for about two hours in the car. Defendant returned to Zorba's, dropped Tina off, and went to meet Barker at a Circle K near their house. Because Barker was not there as planned, Defendant went home. Barker soon arrived home with a stolen car and stolen property. Defendant claimed he helped Barker unload the goods and dispose of the stolen car. To account for the stolen property police found in his possession, Defendant claimed he had bought the items from Barker.

Tina Collins testified by videotape and gave the following story, corroborating Defendant's version. She first met Defendant about two weeks before the murder at a party, where they discussed performing a sex act on Defendant's girlfriend and arranged to meet again on September 4. They talked over the telephone on September 4 and planned to meet at nine o'clock that night to negotiate a deal. Tina did not arrive until 9:10 or 9:15 and joined Defendant in a black TransAm he was driving. They drove to the parking lot of an office building, talked for an hour, went to a convenience store for sodas, and returned to the parking lot to talk some more. After meeting for a couple of hours, Defendant drove Tina back to Zorba's. When asked whether she saw any unusual equipment in the car, Tina said she saw a gun and a police scanner, which she first thought was a walkie-talkie. Nothing in the record disputes Tina's professed observations. (FN2)

FN2. Tina said she did not talk with Defendant again until February 9, when she visited him in prison. According to Tina, she learned from her friend Judy that Defendant was in prison. Judy had been visiting Defendant's cellmate, a man named Paul. While Judy visited Paul, she telephoned Tina and told her that Paul had a friend who wanted to meet her. Tina had previously visited and befriended inmates she did not know. When Defendant got on the telephone, he and Tina recognized each other. Thereafter, Tina visited Defendant in prison regularly.

The prosecutor suggested in closing argument that Tina had never met Defendant until she visited him in prison after the murder and that she therefore fabricated her alibi testimony to help Defendant. Reporter's Transcript, Aug. 13, 1992, at 61.

The jury apparently believed Tina and Defendant less than Barker and found Defendant guilty of first-degree murder. At the sentencing hearing, the trial judge found three statutory aggravating factors and two mitigating factors. In aggravation, the State proved that Defendant (1) had been convicted of a crime for which a life sentence was imposable, [FN3] (2) committed the murder for financial gain, [FN4] and (3) committed the murder in an especially cruel, heinous, or depraved manner. [FN5] The judge found that the mitigating factors, Defendant's drug-impaired capacity to conform his conduct to the law and his codefendant's lenient plea-bargained sentence, were not sufficiently substantial to call for leniency. Accordingly, the judge sentenced Defendant to death.

FN3. A.R.S. § 13-703(F)(1) and (2). Defendant had been convicted of committing four counts of armed robbery while on parole. A life sentence for the conviction was therefore mandatory.

FN4. A.R.S. § 13-703(F)(5).

FN5. A.R.S. § 13-703(F)(6).

DISCUSSION

Defendant takes issue with a number of the trial judge's procedural rulings, arguing that they constituted reversible error. He also challenges the trial judge's findings at the sentencing hearing and the constitutionality of Arizona's death penalty scheme. We consider each of Defendant's arguments.

TRIAL ISSUES

Defendant contends that by twice limiting his cross-examination of Barker, the trial judge violated his right under the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments to confront a key witness. In one instance the judge prohibited the defense from asking Barker what his attorney had said to him about his chances of receiving the death penalty without a plea bargain. In the second instance, the judge barred the defense from probing Barker about his belief in the occult. Defendant charges that both of these rulings infringed his right to effectively cross-examine an important witness and were fundamental error.

1. The confrontation right and the attorney-client privilege

To show Barker had a motive to testify for the State and inculpate Defendant, even if he had to lie, Defendant cross-examined Barker about benefits he expected in return for his plea agreement. Defendant asked Barker whether his attorney had told him that the State might seek the death penalty if Barker did not cooperate with the prosecutor. Barker's lawyer was present and objected on grounds of attorney-client privilege, and the judge sustained the objection.

A defendant has great latitude to cross-examine an "accomplice or co- defendant who has turned State's evidence and testifies on behalf of the State in a trial of his co-defendant." State v. Morales, 120 Ariz. 517, 520, 587 P.2d 236, 239 (1978) (citations omitted). A trial judge who excludes testimony that would show bias and interest in this circumstance may commit reversible error. Id. Even if the defendant fails to object or give an offer of proof when such testimony is precluded, error may be found if the context of the questions makes their purpose clear. Ariz. R. Evid. 103(a).

If cross-examination into privileged areas is necessary to show a witness' bias, the United States Supreme Court has held that the interest of confidentiality can be "outweighed by [the defendant's] right to probe into the influence of possible bias in the testimony of a crucial identification witness." See Davis v. Alaska, 415 U.S. 308, 319, 94 S.Ct. 1105, 1111, 39 L.Ed.2d 347 (1974). In the few reported cases in which the confrontation right has collided with the attorney-client privilege, courts have employed a fact- specific balancing test to resolve the competing interests of confidentiality and the defendant's right to impeach an important government witness. See, e.g., State v. Cascone, 195 Conn. 183, 487 A.2d 186, 190-91 (1985) (trial court's exclusion of a co-defendant's pretrial statement to his attorney that would exculpate the defendant was not harmless error).

In United States ex. rel. Blackwell v. Franzen, the court balanced the relevant interests:

[T]he question in each case must finally be whether defendant's inability to make the inquiry created a substantial danger of prejudice by depriving him of the ability to test the truth of the witness's direct testimony. To answer that question the court must look to the record as a whole and to the alternative means open to the defendant to impeach the witness. The court must ultimately decide whether the probative value of the alleged privileged communication was such that the defendant's right to effective cross- examination was substantially diminished.

688 F.2d 496, 500-01 (7th Cir.1982) (citations omitted), cert. denied, 460 U.S. 1072, 103 S.Ct. 1529, 75 L.Ed.2d 950 (1983).

In Franzen, the defendant cross-examined his accomplice, who had agreed to testify for the state. The defendant elicited testimony from the witness that he had told his own attorney "he was beaten [by the prosecutor] into making that statement [that inculpated defendant]" to show that the prosecutor had induced the accomplice to incriminate the defendant. Id. at 499. The state objected, and the trial court sustained the objection on grounds that the attorney-client privilege "overrides any relevancy it may have to the issues in [the] case." Id. However, because there was already ample evidence in the record to impeach the accomplice's testimony, the circuit court upheld the trial court's ruling. Id. at 501; see also Neku v. United States, 620 A.2d 259, 263 (D.C.1993), cert. denied, 510 U.S. 1003, 114 S.Ct. 577, 126 L.Ed.2d 476 (1993).

As long as the jury heard evidence relevant to Barker's possible motives for testifying against Defendant, we assume it could then fairly assess Barker's truthfulness. No doubt Barker's plea agreement was relevant to his bias and interest. The jury apparently realized this and sent a note to the judge during deliberations asking what benefits Barker received in exchange for his testimony. Reporter's Transcript (R.T.), Aug. 13, 1992, at 110. The jury's note asked, "Does Randy Barker have anything to gain if Towery is convicted? Are we allowed to see the plea agreement?" In response to the note, the judge told the jurors they had all the evidence and instructed them to rely on their personal recollections and collective notes.

At issue then is whether the jury knew what benefits Barker would receive from his plea bargain. If the statement made to Barker by his lawyer was sufficiently probative of Barker's credibility to outweigh the interests protected by the attorney-client privilege, [FN6] then the judge abused her discretion in prohibiting Defendant from asking about a privileged communication.

FN6. The attorney-client privilege, the "oldest of the privileges for confidential communications known to the common law," has been rigorously guarded "to encourage full and frank communication between attorneys and their clients and thereby promote broader public interests in the observance of law and administration of justice." Upjohn Co. v. United States, 449 U.S. 383, 389, 101 S.Ct. 677, 682, 66 L.Ed.2d 584 (1981).

The record shows that even without disclosure of whether Barker's lawyer told Barker that the State would seek the death penalty if he did not cooperate, other evidence informed the jury that Barker knew he could escape death by cooperating and testifying. The jury knew that the State would have pursued the death penalty if Barker were convicted of first-degree murder. Earlier in the day, the jury heard a stipulation that prior to Barker's plea agreement the State had filed a notice of intent to seek the death penalty if Barker were convicted of first-degree murder. The jury knew that Barker then made a plea agreement with the State for second-degree murder. In short, although the jury questioned Barker's benefits if Defendant were convicted, as evidenced by the note to the judge, the jury must have understood all of the benefits Barker received from his plea agreement and testimony when it decided Defendant's guilt. The evidence would have been merely cumulative had the judge permitted Defendant to ask about Barker's privileged communication with his attorney. Moreover, in protecting the attorney-client privilege, the judge did not impair Defendant's ability to obtain the information he wanted. Defense counsel could have established a motive for Barker to lie without invading the attorney-client privilege. He simply could have asked if Barker knew or believed he would have been eligible for the death penalty or a life sentence had he not agreed to testify. In upholding the privilege, therefore, the judge did not abuse her discretion.

2. Cross-examination of Barker's belief in satanism

On cross-examination, the defense asked Barker about his belief in the occult after he revealed that he had dialed straight sixes while feigning a telephone call from the victim's house. [FN7] The judge sustained the State's objection on grounds of relevance, basing her ruling on Ariz. R. Evid. 610 and art. 2, § 12 of the Arizona Constitution. [FN8] These provisions bar questioning a witness about religious beliefs as a way to enhance or attack the witness' credibility. On appeal, Defendant contends that testimony about Barker's religious beliefs, if such they were, was not offered to impeach his credibility but to show that the antisocial tenets of his beliefs disposed Barker to engage in criminal conduct and to commit the murder.

FN7. During cross-examination, Barker was asked what number he dialed when he pretended to use the telephone in Jones' house. Barker responded, "I dialed straight sixes." The testimony continued:

Q: Why did you dial those numbers?

A: Because of--I used to have an old belief in the occult.

Q: When did you do away this that belief?

Mr. Ditsworth [for the State]: Relevance, Your Honor.

The Court: Sustained.

Mr. Hazel [for Defendant]: Pardon me, Your Honor, I didn't--

The Court: Sustained.

Mr. Hazel: Your Honor, can we approach on that point?

The Court: Later.

Mr. Hazel: But, in fact, you had an alter [sic] in your--a Satanic alter in your room; is that correct?

Mr. Ditsworth: Same objection.

The Court: Sustained.

R.T., Aug. 5, 1992, at 112-13.

After excusing the jury, the judge asked defense counsel why the ruling should be reversed. Counsel explained that he had seen what looked like a satanic altar in a photograph of Barker's bedroom and wanted to ask Barker to confirm its identity. He continued, "I think it's important that the jury know that he has some different type of beliefs that other people may not." The trial judge asked for case law showing that satanism was an exception to the rule prohibiting a party from introducing evidence of a witness' religious beliefs. Id. at 140-41. Counsel agreed to find authority but never offered any.

FN8. Ariz. R. Evid. 610 provides:

Evidence of the beliefs or opinions of a witness on matters of religion is not admissible for the purpose of showing that by reason of their nature his credibility is impaired or enhanced.

(Emphasis added.)

Art. 2, § 12 of the Arizona Constitution states:

No ... person [shall] be incompetent as a witness or juror in consequence of his opinion on matters of religion, nor be questioned touching his religious belief in any court of justice to affect the weight of his testimony.

(Emphasis added.)

A witness' religious beliefs are admissible if offered for some legitimate purpose other than attacking witness credibility. See State v. West, 168 Ariz. 292, 296, 812 P.2d 1110, 1114 (1991) (reference to religion is proper when used to justify defendant's conduct); State v. Stone, 151 Ariz. 455, 458, 728 P.2d 674, 677 (App.1986) (if evidence of religious belief "is probative of something other than veracity, it is not inadmissible simply because it may also involve a religious subject as well."). Defendant argues that the evidence was relevant to an issue other than Barker's veracity. Had he been allowed to develop testimony about Barker's satanic beliefs, the jury might have been persuaded to believe that Barker, not Defendant, was the killer. In addition, although the jury nevertheless could have found Defendant's involvement sufficient to convict him for felony murder, his death eligibility was not a foregone conclusion. Although the judge found beyond a reasonable doubt that Defendant was the killer, evidence that Barker was profoundly touched by some satanic belief might have altered that finding.

Defendant, however, made no offer of proof of what Barker's testimony would have shown. Nor does the context of the question indicate the nature of Barker's satanic belief or show it was substantively relevant. When an objection to the introduction of evidence has been sustained, an offer of proof showing the evidence's relevance and admissibility is ordinarily required to assert error on appeal. State v. Bay, 150 Ariz. 112, 115, 722 P.2d 280, 283 (1986); MORRIS K. UDALL ET AL., ARIZONA PRACTICE: LAW OF EVIDENCE § 13, at 20 (2d ed.1982). Given that counsel normally does not know in advance what a hostile witness will say on cross-examination, the offer-of-proof requirement for considering a claim on appeal may be relaxed when the court sustains an objection to a question asked on cross-examination. JOHN W. STRONG, ET AL., 1 MCCORMICK ON EVIDENCE § 51, at 197 (4th ed.1992). Even so, something more than speculation about possible answers is required to show prejudice. At a minimum, an offer of proof stating with reasonable specificity what the evidence would have shown is required. See id. at 197-98. In Arizona, it has been suggested that counsel be required to discover evidence that would make the proffered testimony relevant and make it known to the court. State v. Quinn, 121 Ariz. 582, 585, 592 P.2d 778, 781 (App.1978).

We recognize, however, that discovery in criminal cases is much more limited than in civil cases. Victims of crimes, for example, can refuse interview requests by defense counsel under the Victims' Bill of Rights. Ariz. Const. art. 2, § 2.1; Ariz. R.Crim. P. 39(b)(11). Nonetheless, when the context of the examination fails to reveal the nature of the expected answer, the proponent of the precluded evidence must seek permission from the trial judge to make the offer of proof so that the reviewing court can determine whether the trial judge erred in precluding the evidence. STRONG, ET AL., supra § 51, at 197 n. 10; see also State v. Affeld, 307 Or. 125, 764 P.2d 220, 222 (1988). It is remotely conceivable that Barker might have revealed he was driven by a satanic force or some other evil belief to commit criminal acts. The only hint of a satanic motive for Barker's participation in the crime, however, was his dialing sixes on the telephone. That alone has little probative value in establishing a motive to kill. Assuming Barker had a satanic altar in his room, Defendant failed to discover how often Barker used it and how its use was related to his criminal conduct. In fact, Barker's claim that he used to believe in the occult indicates that the alleged altar no longer had any religious significance to him. Defendant's failure to establish the connection between Barker's old belief in the occult and the crime by an offer of proof in the record makes it impossible to evaluate whether the trial judge unfairly limited Defendant's cross-examination of Barker. On this record, we see no probative value in the precluded evidence apart from its effect on Barker's credibility. Thus we find no error in the judge's precluding it.

B. Defendant's right to a free transcript of a previous, unrelated trial

Before trial, Defendant asked the court by written motion to provide a free transcript of a prior trial in which he had been convicted of armed robbery. That trial took place in mid-March 1992, about six months after Jones' murder and about five months before Defendant's homicide trial. He stated that he needed the transcript because the prosecutor had filed notice that the State intended to call witnesses from the armed robbery trial. [FN9] The judge denied his request on grounds that "no good cause has been shown for the need of the trial transcripts," advising him to renew his motion "setting forth some facts which demonstrate an actual need other than the bare conclusion that he needs the transcript 'to prepare a defense'." Minute Entry, June 13, 1992, at 19. Defendant made no further request for the transcript. On appeal, Defendant claims that in denying him valuable defense information, the judge violated his equal protection and due process rights.

FN9. Defendant used plastic tie wraps, like the ones used during Jones' murder, during the armed robbery. He had also used a police scanner in the armed robbery. Barker told police that Defendant took a police scanner to Jones' house. The State wanted to call the armed robbery victim to prove the identity of Jones' killer and filed a motion to admit prior bad acts. The State later withdrew its motion.

The United States Supreme Court has held that requiring an indigent defendant to demonstrate a particularized need for a free transcript of a prior mistrial or preliminary hearing can violate equal protection. Britt v. North Carolina, 404 U.S. 226, 227, 92 S.Ct. 431, 433- 34, 30 L.Ed.2d 400 (1971); Roberts v. LaVallee, 389 U.S. 40, 88 S.Ct. 194, 19 L.Ed.2d 41 (1967); Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12, 17, 76 S.Ct. 585, 590, 100 L.Ed. 891 (1956) ("In criminal trials, a State can no more discriminate on account of poverty then on account of religion, race, or color."). Only financial need, not particularized need, must be shown. Britt held that two factors are relevant in determining if a trial court has erred by refusing an indigent defendant a free trial transcript: (1) the value of the transcript to the defendant for an effective defense at trial or on appeal, and (2) "the availability of alternative devices that would fulfil the same functions as the transcript." Britt, 404 U.S. at 227, 92 S.Ct. at 434. [FN10] The transcript from a prior mistrial has been recognized as a valuable resource for impeaching witnesses, guiding discovery, and developing trial strategy. Id. at 232, 92 S.Ct. at 436 (Douglas, J., dissenting). Thus, when a transcript from a mistrial is requested for use at the retrial, the value of the transcript is generally presumed without a showing of specific need. United States v. Rosales-Lopez, 617 F.2d 1349, 1355-56 (9th Cir.1980), aff'd, 451 U.S. 182, 101 S.Ct. 1629, 68 L.Ed.2d 22 (1981). A preliminary hearing transcript may also be presumed to have value in connection with a pending trial. See id.

FN10. In Britt the Court upheld the trial court's decision not to provide a transcript to the defendant. The same judge presided, and the same counsel appeared. Because the same court reporter, who knew the attorneys and the judge, was present and could have readily provided defense counsel with transcriptions from the prior mistrial if informally asked, the Court found that the defendant had adequate alternative devices available. See State v. Tomlinson, 121 Ariz. 313, 589 P.2d 1345 (App.1978) (reviewing state and federal cases on whether the defendant had an adequate alternative device for a trial transcript)

In this case, however, Defendant asked for a free transcript of his trial on an unrelated charge. Our cases have held that there is no presumed value to the defense in the transcript of a co-defendant's trial. See State v. Tison, 129 Ariz. 526, 540, 633 P.2d 335, 349 (1981) (indigent defendant must show special need in requesting a transcript of co-defendant's trial), cert. denied, 459 U.S. 882, 103 S.Ct. 180, 74 L.Ed.2d 147 (1982); State v. Razinha, 123 Ariz. 355, 358, 599 P.2d 808, 811 (App.1979) (citing cases). But see State v. Campbell, 215 N.W.2d 227 (Iowa 1974). Although the present question is one of first impression for this court, we partially answered it in Tison. Tison claimed the trial judge erred in denying him a free transcript of his co-defendant's trial on the same charges. In holding that there is no presumed value of a co-defendant's trial transcript even when the same witnesses are called, we emphasized that the constitution does not require the State to provide every service that "might be of benefit to an indigent defendant ... but only to assure the indigent defendant an adequate opportunity to present his claims fairly...." Tison, 129 Ariz. at 540, 633 P.2d at 349, quoting Ross v. Moffitt, 417 U.S. 600, 616, 94 S.Ct. 2437, 2447, 41 L.Ed.2d 341 (1974).

Because a mistrial effectively serves as a "dry run" of the State's case, a transcript is ordinarily considered invaluable as a discovery device and tool for impeaching prosecution witnesses at the subsequent trial. Britt, 404 U.S. at 228, 92 S.Ct. at 434. But when the transcript sought is that for an unrelated charge--even against the same defendant--the crime, victim(s), time, place, facts, and witnesses are ordinarily different. Thus, the rationale for the presumption of need does not apply to a transcript of the defendant's trial on unrelated charges. Its value must be established, and unless the defendant demonstrates a specific need for the trial transcript, the court does not err in concluding that the transcript is not necessary for an effective defense. The mere fact that a witness who testified at the first, unrelated trial may be called at the second is not sufficient for a presumption of value. See Fisher v. Hargett, 997 F.2d 1095, 1098 (5th Cir.1993) (free transcript of a prior trial involving a different victim and offense at a different time not constitutionally required); McAllister v. Garrison, 569 F.2d 813, 815 (4th Cir.1978) (holding that defendant must make a reasonable showing of transcript's value even though common witnesses called), cert. denied, 436 U.S. 928, 98 S.Ct. 2824, 56 L.Ed.2d 771 (1978). When asking for a free transcript of an unrelated trial, therefore, a defendant may be required to demonstrate some reasonable probability of defense value.

Defendant said he needed the robbery trial transcript because the State intended to call common witnesses from the armed robbery trial. Despite the judge's request, Defendant made no further showing of particularized need for the transcript. Without a sufficient showing of the transcript's value for an effective defense, the judge did not err in denying Defendant a free copy. We reach this conclusion, as we must, the same way the judge did, on the record as it then existed.

Although the robbery victim did not testify at the homicide trial, three other witnesses testified at both trials. At the murder trial, one of these witnesses, Defendant's roommate John Meacham, testified that he overheard Defendant make an inculpatory statement. The same prosecutor had elicited similar testimony from Meacham at the robbery trial. Defendant argues that the statements attributed to him by Meacham refer to the same incident but were introduced at two separate trials to prove two separate crimes. Because Defendant had different lawyers at each trial, his trial lawyer in the present case may not have known about Meacham's previous testimony without reading the transcript.

Defendant is correct that the transcript of Meacham's robbery trial testimony might have alerted defense counsel that the State was making inconsistent use of Meacham's testimony. Thus the transcript might have helped impeach Meacham at the murder trial. [FN11] His testimony at both trials was offered to prove Defendant's culpability in unrelated crimes. But neither Defendant nor the trial judge could have reasonably anticipated that the prosecutor would make inconsistent use of the same testimony. Because the prosecutor did not inform the court of his intent to elicit the same testimony from an unrelated trial, the court had no way of knowing that the requested transcript might help the defense. If the transcript would have been valuable to Defendant, any prejudice caused by the denial of a free copy was attributable not to the trial judge, who ruled correctly on the record before her, but to the prosecutor. Thus, we find no equal protection violation.

FN11. We note that the transcript would have been of no value to Defendant insofar as it pertained to the testimony of two of the common witnesses. These witnesses were police officers who had been involved in the robbery and murder investigations. They testified at this trial only about items seized in the murder investigation. The robbery trial transcripts of these two witnesses would have been useless to the defense for discovery or impeachment purposes.

C. Defendant's inculpatory statement--judicial estoppel and prosecutorial misconduct

At Defendant's prior armed robbery trial Meacham testified that he overheard Defendant say, "I tried to get this old man to do what I wanted him to do, but he wouldn't do it." State v. Towery, Maricopa County No. CR 91- 02512, R.T., Mar. 10, 1992, at 98. At the homicide trial, Meacham was again called to testify. His testimony approximated the testimony he gave in the armed robbery trial: he said that he heard Defendant tell Barker that he was "having a hard time with an old man so he had--he had a hard time tying him up, so he had to knock him down." The victims of both crimes were older men.

Because Defendant had different counsel at the two trials and was denied a transcript of the robbery trial, we must assume that his trial attorney in the present case did not know the substance of Meacham's testimony at the robbery trial. Moreover, before putting Meacham on the stand in the murder trial, the prosecutor failed to notify the court or defense counsel that he would present evidence of the same admission Meacham described in the robbery trial. The context of Meacham's testimony at both trials makes it quite clear, and the State concedes, that Meacham heard one admission about one crime. But the admission was used in two trials to help prove two unrelated criminal acts. Defendant claims that by presenting evidence of a single incident at two separate trials to prove two separate, unrelated crimes, the prosecutor violated Defendant's due process rights and the doctrine of estoppel by engaging in misconduct.

1. Judicial Estoppel

Defendant argues that "the prosecutor [used] the same evidence to convict the appellant of two separate crimes ... attempting to prove a fact in one trial and seeking to prove an inconsistent fact in another trial with the same evidence." Opening Brief at 32. The error in using the evidence, in Defendant's words, is that it " 'perverts' the integrity of our system of jurisprudence." Id. at 35. Protecting the integrity of the judicial process is the universally recognized purpose of judicial estoppel. See, e.g., 18 C. WRIGHT, A. MILLER & E. COOPER, FEDERAL PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE § 4477 (1981 and Supp.1990); 1B J. MOORE, J. LUCAS & T. CURRIER, MOORE'S FEDERAL PRACTICE 405[8], at 239, 240 (2d ed.1988); Scarano v. Central R.R., 203 F.2d 510, 513 (3d Cir.1953).

Judicial estoppel prevents a party from taking an inconsistent position in successive or separate actions. This court has long recognized that

[a]s a general rule, a party who has assumed a particular position in a judicial proceeding is estopped to assume an inconsistent position in a subsequent proceeding involving the same parties and questions.

Martin v. Wood, 71 Ariz. 457, 459, 229 P.2d 710, 711-12 (1951) (citing 31 C.J.S. ESTOPPEL § 119, at 381). Judicial estoppel is not intended to protect individual litigants but is invoked to protect the integrity of the judicial process by preventing a litigant from using the courts to gain an unfair advantage. See 31 C.J.S. ESTOPPEL § 121, at 260; see also Yanez v. United States, 989 F.2d 323, 326 (9th Cir.1993); Yniguez v. Arizona, 939 F.2d 727, 739 (9th Cir.1991); Russell v. Rolfs, 893 F.2d 1033, 1037 (9th Cir.1990), cert. denied, 501 U.S. 1260, 111 S.Ct. 2915, 115 L.Ed.2d 1078 (1991); In re Cassidy, 892 F.2d at 641. Although judicial estoppel is usually invoked in civil cases, [FN12] courts have also applied it in criminal cases. See, e.g., State v. Washington, 142 Wis.2d 630, 419 N.W.2d 275, 277 (App.1987).

FN12. See, e.g., State v. Ellison, 26 Ariz.App. 547, 549, 550 P.2d 101, 103 (1976).

The doctrine's application to criminal cases usually involves a defendant who asserts one position at trial and another on appeal. See Harrison v. Labor & Indus. Review Comm'n, 187 Wis.2d 491, 523 N.W.2d 138, 140 (App.1994). Nonetheless, criminal courts have indicated that judicial estoppel would preclude the state from changing its version of the facts in separate proceedings involving the same matter to protect the defendant's right to due process. See People v. Gayfield, 261 Ill.App.3d 379, 199 Ill.Dec. 123, 128-29, 633 N.E.2d 919, 924-25 (1994) (suggesting that the state would be estopped from inconsistently claiming in separate proceedings that different defendants shot the same victim); Russell v. Rolfs, 893 F.2d at 1037-39 (state prohibited from arguing that criminal defendant's appellate petition is procedurally barred in state court after successfully arguing in district court that defendant had an adequate state remedy).

We believe the doctrine of judicial estoppel is no less applicable in a criminal than in a civil trial. Any other rule would permit absurd results. For example, if the state had evidence that a defendant admitted robbing the convenience store, absent judicial estoppel the state could use that evidence to convict the defendant of every convenience store robbery in the city, affirming the evidence as relevant in each case, all the while knowing that the defendant made only one admission of a single act.

Three requirements must exist before the court can apply judicial estoppel: (1) the parties must be the same, (2) the question involved must be the same, and (3) the party asserting the inconsistent position must have been successful in the prior judicial proceeding. See Standage Ventures, Inc. v. State, 114 Ariz. 480, 562 P.2d 360 (1977). In the present case the parties are the same. Because Defendant's admission could only pertain to one of the crimes, the question involved in both proceedings is also the same: did Defendant admit committing the charged crime in Meacham's presence? However, even though the parties and the questions are the same, a majority of courts, including Arizona, refuse to invoke judicial estoppel unless the position first asserted was successfully maintained. [FN13] Taylor v. State Farm Mutual Auto. Ins. Co., 182 Ariz. 39, 44, 893 P.2d 39, 44 (App.1995),vacated in part, 185 Ariz. 174, 913 P.2d 1092 (1996).

FN13. The minority view allows judicial estoppel "even if the litigant was unsuccessful in asserting the inconsistent position, if by his change of position he is playing 'fast and loose' with the court." Keenan v. Allan, 889 F.Supp. 1320, 1360 (E.D.Wash.1995), quoting Morris v. California, 966 F.2d 448, 452-53 (9th Cir.1991), cert. denied, 506 U.S. 831, 113 S.Ct. 96, 121 L.Ed.2d 57 (1992).

The prior position was successfully maintained only if the party gained judicial relief as a result of asserting the particular position in the first proceeding. See id. at 44, 893 P.2d at 44; Standage, 114 Ariz. at 484, 562 P.2d at 364; State Farm Auto. Ins. Co. v. Civil Service Employees Ins. Co., 19 Ariz.App. 594, 600, 509 P.2d 725, 731 (1973). Prior success has also been defined as requiring that the court in the prior action accepted the first position. Edwards v. Aetna Life Ins. Co., 690 F.2d 595, 598 (6th Cir.1982); see also Chaveriat v. Williams Pipe Line Co., 11 F.3d 1420, 1427 (1993) (litigant must obtain victory on prior ground); Rand G. Boyers, Precluding Inconsistent Statements: The Doctrine of Judicial Estoppel, 80 NW. U.L. REV. 1244, 1256 (1986) (the requirement of prior judicial acceptance "is satisfied whenever a prior court 'has adopted the position [contrary to that now] urged by that party, either as a preliminary matter or as part of a final disposition.' ") (citations omitted) (alterations by author).

Prior success is a prerequisite to the application of judicial estoppel because absent judicial acceptance of the prior position, there is no risk of inconsistent results. See Edwards, 690 F.2d at 599; see also Boyers, supra, 80 NW. U.L. REV. at 1253. Because the judicial process is unimpaired absent inconsistent results, and because judicial estoppel is recognized to protect the integrity of the judicial process, invocation of the doctrine is unwarranted without prior success on--or judicial acceptance of-- the first position. See USLIFE Corp. v. U.S. Life Ins. Co., 560 F.Supp. 1302, 1305 (N.D.Tex.1983) (citing Edwards, 690 F.2d at 599); C. WRIGHT, A. MILLER & E. COOPER, FEDERAL PRACTICE & PROCEDURE § 4477 (1983).

The guilty verdict on the armed robbery charge establishes that the jury accepted the State's position that Defendant committed that crime. The robbery verdict does not, however, establish that Defendant's admission to committing the armed robbery was a key element of the guilty verdict. Indeed, it is entirely possible that the jury in that case gave little or no consideration to Meacham's testimony, especially if his testimony constituted only an insignificant fraction of the total evidence offered to establish Defendant's guilt. See Boyers, supra, NW. U.L. REV. at 1257. For this reason, judicial estoppel is generally not applied when the first inconsistent position was not a significant factor in the initial proceeding. Id. at 1263.

Rather, the court, keeping in mind the 'unnecessary hardship' that may result from invoking judicial estoppel when the position was unimportant in the initial proceeding, determines whether the importance of the issue in the particular case justifies invocation of the doctrine.

Id. (citations omitted).

Thus, to determine if the prior success requirement for invocation of judicial estoppel was met in the armed robbery trial, this court must examine the record of that trial to determine whether Meacham's testimony was arguably significant to the jury's determination of Defendant's guilt. Id. In other words, can we conclude that the judicial relief obtained by the State in the armed robbery conviction was arguably due to Meacham's testimony? See Standage, 114 Ariz. at 484, 562 P.2d at 364. [FN14)

FN14. Although Defendant supplemented his brief with the portion of the transcript of the armed robbery trial containing Meacham's examination, he did not provide this court with the entire transcript. We later ordered that the record of Defendant's prior armed robbery trial be produced in its entirety and included as part of this record.

Having reviewed the entire record of the armed robbery trial, it is clear that Meacham's testimony was an insignificant factor in obtaining a conviction in that trial. All four robbery victims separately identified Defendant from a photographic line-up. They also testified at trial. When Defendant was arrested for the armed robbery, he had four credit cards of one of the victims in his wallet. In his home police found a gun identified by one of the victims as the gun used in the robbery, as well as clothing similar to that worn by the perpetrator of the robbery. Defendant also had a police scanner on his person when arrested; the robbery victims noted that the robber had an identical police scanner with him at the time of the crime. The license plate of the car Defendant drove to the robbery matched that of Barker's car, and Meacham testified that Defendant had access to Barker's car. Meacham's testimony about Defendant's admission came in as an unresponsive answer to a single question and was never mentioned again in the examination of Meacham or any other witness. The prosecutor never referred to Defendant's alleged admission in his opening statement or closing argument.

We conclude that Meacham's testimony about Defendant's inculpatory statement was at most an insignificant factor in light of the overwhelming evidence of Defendant's guilt on the armed robbery charge. Because judicial estoppel is to be invoked cautiously, on these facts we are unprepared to say that the prior position was successfully maintained. We therefore decline to invoke judicial estoppel here to preclude Meacham's testimony at the murder trial. Thus, we examine whether the prosecutor's actions constituted misconduct justifying reversal.

2. Prosecutorial misconduct

At oral argument before this court, the State conceded that the prosecutor elicited testimony of an admission about a single incident to help establish Defendant's guilt of two unrelated crimes. The prosecutor justified his actions by telling this court that he had been mistaken about presenting Defendant's admission at the robbery trial. As the murder investigation developed, the prosecutor became less convinced that Defendant's admission related to the armed robbery and more convinced that Defendant had been describing events of the murder. The State supported its use of Defendant's admission at the murder trial because it was made after the murder, better fit the facts of the murder, [FN15] and was therefore relevant evidence in the murder trial. The State submits it was for the jury to decide what weight to give Meacham's testimony. Further, the State argues that Defendant was free to ask Meacham questions that would have explained the alleged admission, thereby attributing the admission to the robbery rather than to the murder.

FN15. The prosecutor explained at oral argument that the oldest victim of the previous crime was 55 years old. Jones was 68 years old when he was murdered. Defendant's reference to an "old man" convinced the prosecutor that Defendant had been discussing Jones rather than the robbery victim when Meacham overheard him.