53rd murderer executed in U.S. in 2005

997th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

4th murderer executed in North Carolina in 2005

38th murderer executed in North Carolina since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

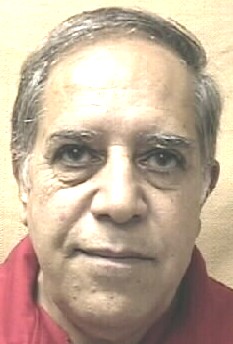

Elias Hanna Syriani Arab / M / 52 - 67 |

Teresa Yousef Syriani Arab / F / 40 |

Summary:

Syriani and his wife, Teresa Yousef Syriani, were separated. Syriani was living in a motel, and his wife with their children in their home. There was evidence of past physical abuse by Syriani against his wife. One night shortly before midnight, Syriani drove to their home. As his wife drove her car onto a nearby street, Syriani blocked her way with his van. Defendant got out of his van, gestured, and chased after her car as she put it in reverse. As his wife sat in her car, defendant began stabbing her with a screwdriver through the open door or window, while their ten-year-old son, John, sat in the seat beside her. John was unable to stop his father, got out and ran home to get his older sister. At least two neighbors watched from their homes as defendant stabbed his wife and then walked away. Teresa Syriani died twenty-eight days later. She suffered numerous stab wounds in the attack, the fatal wound a three-inch deep puncture wound to the right temple. Syriani stopped at a nearby fire station for first aid, claiming he was battered by his wife. He was covered in blood, but had only some light scratches on his arm and shoulder. Police were called and he was arrested. The murder weapon, a screwdriver, was never found.

Citations:

State v. Syriani, 333 N.C. 350, 428 S.E.2d 118 (N.C. 1993) (Direct Appeal).

Syriani v. Polk, 118 Fed.Appx. 706 (4th Cir. 2004) (Habeas).

Final Meal:

Declined.

Final Words:

"I love you," he said to the Egglestons. "I love everybody." Over the next 10 minutes he smiled, grimaced, cried. Mostly he talked to the Egglestons. He mouthed each word carefully. We could pick up only fragments.

"I want them to be happy." "Fifteen years." "I hope ... I hope ... I really loved her."

(Prepared Statement: "I want to thank God first for everything that happened in my life. I want to thank my children. I want to thank my family, especially my sister, Odeet. I want to thank all the beautiful friends who share with me my sufferings for 15 years and four months and they so encouraged me, specifically Mr. and Mrs. Meg Eggleston who become a sister to me. She helped me a lot to accept everything. I thank everyone from the staff, nurses, chaplains. I thank everyone.")

Internet Sources:

SYRIANI, ELIAS H.

DOC Number: 0398002

DOB: 01/07/1938

RACE: OTHER

SEX: MALE

DATE OF SENTENCING: 06/12/91

COUNTY OF CONVICTION: MECKLENBERG COUNTY

FILE#: 90062527

CHARGE: MURDER FIRST DEGREE (PRINCIPAL)

DATE OF CRIME: 07/28/1990

North Carolina Department of Correction (Chronology / Press Release)

Elias Syriani - Chronology of Events

10/13/2005 - Correction Secretary Theodis Beck sets November 18, 2005 as the execution date for Elias Syriani.

10/3/2005 - U.S. Supreme Court denies Syriani's petition for a writ of certiorari.

3/12/1993 - North Carolina Supreme Court confirms Syriani's conviction and sentence of death

6/12/1991 - Elias Syriani sentenced to death in Mecklenburg Co. Superior Court for the murder of Teresa Yousef Syriani.

North Carolina Department of Correction

For Release: IMMEDIATE

Contact: Public Affairs Office

Date: Oct 13, 2005

Phone: (919) 716-3700

Execution date set for Elias Hanna Syriani

RALEIGH - Correction Secretary Theodis Beck has set Nov. 18, 2005 as the execution date for inmate Elias Hanna Syriani. The execution is scheduled for 2 a.m. at Central Prison in Raleigh. Syriani, 67, was sentenced to death June 12, 1991 in Mecklenburg County Superior Court for the 1990 murder of Teresa Yousef Syriani.

Central Prison Warden Marvin Polk will explain the execution procedures during a media tour scheduled for Monday, November 14 at 10:00 a.m. Interested media representatives should arrive at Central Prison’s visitor center promptly at 10:00 a.m. on the tour date. The session will last approximately one hour.

The media tour will be the only opportunity to photograph the execution chamber and deathwatch area before the execution. Journalists who plan to attend the tour should contact the Department of Correction Public Affairs Office at (919) 716-3700 by 5:00 p.m. on Friday, Nov. 11.

ATTENTION EDITORS: A photo of Elias Hanna Syriani (#0398002) can be obtained by using the "Offender Search" function on the Department of Correction Web site at www.doc.state.nc.us. For more information about the death penalty, including selection of witnesses, click on “The Death Penalty” link.

"N.C. man executed for 1990 murder of wife," by Estes Thompson. (Associated Press Nov. 18, 2005)

RALEIGH, N.C. - A 67-year-old immigrant who stabbed his wife to death with a screwdriver after she threatened divorce was executed by injection Friday after the governor rejected his children's' plea for clemency.

Elias Syriani was pronounced dead at 2:12 a.m. at Central Prison, where he had visited and hugged his children beforehand after 15 years locked away from their touch. The children - including a son who witnessed the attack and testified against Syriani - argued that letting him live would allow them to restore their connection to their mother, Teresa.

In his final statement, Syriani thanked his family and friends who shared "with me my sufferings for 15 years and four months and they so encouraged me." Syriani looked into the witness room, just on the other side of thick glass panes, when he was wheeled on a gurney into the death chamber and smiled at a couple who had visited him regularly for the past four years. His children, brother Tony Syriani and sister Odeet Syriani weren't there, nor were the children.

Two Charlotte detectives, six prison employees and five reporters watched the execution in addition to the two friends. Syriani was the fourth execution this year in North Carolina. In an animated conversation through the glass, Syriani appeared to say that he wanted his children to be happy and that he loved his wife, who said she wanted a divorce before she was killed. "This is a day of overwhelming sadness," defense lawyer Henderson Hill said after the execution. "Tonight we punished four innocent children already scarred by family violence. ... By taking the life of a man in the process of giving life back to his kids, we betray our own humanity."

Russ Sizemore, a lawyer representing the children, said it was "incomprehensible" that Easley denied clemency after hearing from Rose, Janet and John Syriani and Sarah Barbari, who had been raised by their aunt and uncle in Chicago after their mother died.

At the time of the killing, Syriani was living apart from his family and was under a restraining order. The children "have traveled so far in the process of healing from the terrible wounds of a horrible domestic tragedy that it is nothing short of cruel that their journey would be violently interrupted tonight by another death, a death entirely within our power to prevent," Sizemore said.

Easley said in a statement that he found "no convincing reason to grant clemency and overturn the unanimous jury verdict affirmed by the state and federal courts."

Syriani was convicted in the death of his wife, Teresa, 40, who was stabbed 28 times with a screwdriver in Charlotte. She died 26 days later from the attack that happened after her husband stopped her as she drove home from work and tried to get away from him. The children hadn't seen their father on death row until two years ago and have since said they have forgiven him. Part of their forgiveness stemmed from learning about his traumatic upbringing as an Assyrian Christian in Jerusalem and Jordan.

Easley has granted clemency twice since taking office in 2001, but has not spared the life of any death row inmate since January 2002. North Carolina governors have granted clemency only three other times since the state resumed executions in 1984 after a hiatus while the U.S. Supreme Court determined its constitutionality.

Nationally, clemency was granted 186 times - including 167 commutations by the Illinois governor in 2003 - between 2001 and 2005, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

"Eyewitness to a killer's execution - Charlotte man, 67, executed today," by Tommy Tomlinson. (Nov. 18, 2005)

RALEIGH (6:40 a.m.) - The door opened at the back of the death chamber and they wheeled Elias Syriani in. He was smiling. He was strapped to a gurney, lying on his back, a blue sheet covering his body, two pillows propped under his head.

You could see a pink-and-blue beaded necklace around his neck. You could see the edges of a white curtain at the sides of the window. You could not see the IVs in his arms. The tubes ran behind him, out of sight, and in a few minutes they would deliver the chemicals that would kill him. The clock in the witness room at Central Prison said 1:50 a.m. Friday.

An execution is such a huge thing but it happens in such a small space. The preparation room, just outside the death chamber, is so tiny you can stand in the middle and touch both walls. The death chamber, maybe half again as big. The witness room, the size of a walk-in closet.

Fifteen of us crowded in there – six prison employees, five reporters, two Charlotte-Mecklenburg police detectives, two of Syriani’s friends. All that separated us from him was two panes of glass. His eyes settled on his friends, Meg and Donald Eggleston, sitting on the front row. They were close enough to touch. But no one on our side could hear him. All we could do was try to read his lips.

"I love you," he said to the Egglestons. Then: "I love everybody." This is why he was there on the gurney.

Elias and Teresa Syriani were married 15 years and had four children. Syriani had been beating his wife. She got police to remove him from their Charlotte home. She filed for divorce. One night in 1990, as she drove home from work, he waited for her near the home they used to share. He blocked her car with his van. He got out and reached into the car and stabbed her 28 times with a screwdriver. Their son was in the car with her. Syriani spent his last day on earth with his children.

After the murder, the kids – Rose, Sarah, John and Janet – wrote their father out of their lives. But two years ago, after an emotional visit, they chose to forgive. Last week they met Gov. Mike Easley at their father’s clemency hearing. They asked him to stop the execution. When the kids arrived at the prison Thursday morning, Easley still hadn’t decided. Russell Sizemore, the kids’ lawyer, gave this account: They visited their father from 10 a.m. on, stopping only for short breaks. It was the first time they had touched him in 15 years.

About 7:30 p.m., Henderson Hill – Elias Syriani’s lawyer – got word from the governor’s office. He went up to see his client. Guards moved the kids out so Hill could go in. They crossed paths in the hallway and they saw the news in his eyes. Their last chance, gone. They left the prison at 11 p.m., crying so hard they could barely stand. Syriani’s family decided they would not witness the execution.

He did not want a last meal. At 1 a.m., he stripped to his shorts and was strapped to the gurney. He gave a short statement to prison officials, thanking God and his family and his friends and the prison staff. At 1:40, in the witness room, they dimmed the lights. At 1:50, Syriani was wheeled into the death chamber.

Over the next 10 minutes he smiled, grimaced, cried. Mostly he talked to the Egglestons. He mouthed each word carefully. We could pick up only fragments. "I want them to be happy." "Fifteen years." "I hope ... I hope ... I really loved her."

At 2 a.m., three unseen executioners plunged syringes into IV tubes. One of the tubes led to an empty bag. The executioners will never know which two of them sent chemicals into Syriani’s veins. The first chemical was sodium pentothal, to put him to sleep. He smiled at the Egglestons one last time. "With all my heart," he said.

He looked up at the ceiling. Under the blue sheet, his chest heaved once. Then his mouth opened and his eyes closed and his head sank into the pillows. Meg Eggleston stood up, hands fluttering. A guard helped her leave the room.

The next chemical was Pavulon, a paralyzing drug. The last was potassium chloride, which stops the heart. The blue sheet no longer moved. Donald Eggleston whispered: "Oh, dear God." The heart monitor in another room had to run flat for five minutes before death was official.

For a long quiet time, there in the dark room, we watched him lie still. Fifteen years ago, Elias Syriani killed his wife. Friday morning, the state of North Carolina killed Elias Syriani. At 2:12 a.m., the curtain closed.

"Dad killed Mom, but they can't picture him gone," by Tommy Tomlinson. (Sun, Nov. 13, 2005)

RALEIGH -- Sarah holds the bag close so the memories won't fall out. It's a plain black tote bag but on the outside are clear plastic sleeves. Room for five photos. The top row has one of Sarah's husband, and one of them dancing at their wedding, and an ultrasound of the baby she's due to deliver in April. The bottom left has a photo of Sarah with her siblings -- John, Janet and Rose. The last photo shows their parents. Teresa and Elias Syriani. A smiling young couple. That picture was taken a long time ago.

In 1990, Elias killed Teresa. He blocked her car in the street near her Charlotte home and he stabbed her 28 times with a screwdriver. In 1991, he was sentenced to death. On Friday, he is due to be executed.

For years the children hated him. They burned with fury when people said his name. But now they are trying to save their father's life. And they know people are wondering why. Why have they traveled the state, pleading for support, weeping in front of strangers? Why did they shake off their nerves and go on "Good Morning America" and "Larry King Live"? Why are they begging Gov. Mike Easley to spare the man who killed their mother? Why are they doing this to themselves?

They don't have the words. But they do have pictures.

Memories in soft focus

"I can see these things in my head, so vividly," Sarah says, and the other kids nod, they can see them, too.They remember this: Elias Syriani worked at a machine shop. He would come home with steel shavings in his hair. He would sit in his chair and corral the kids in his arms and they would pick the shavings out. They remember this: Some nights he would give the kids tweezers and they would pluck the hair from his ears. He would squeal, acting like they were hurting him, and the kids would lose their breath laughing. Janet remembers her dad coming to school to have lunch with her. John remembers staying up all night with his dad so they could put together Janet's pink bike. This was the life they had. Their father was a part of it.

On Wednesday, when they visited him at Central Prison, he reminded them of the time they took a vacation to Myrtle Beach. Rose had a dog named Cookie and she wouldn't leave without it. But when they got there they couldn't find a hotel that took pets. They went to a campground but the dog started barking and other campers complained. So their dad took the dog to the beach at 4 in the morning so everybody else could sleep. "I had forgotten how much I loved that dog," Rose says. "That was my childhood. That was a piece of me."

They have even more stories about their mom. How she used to wait with Rose every day at the school bus stop. How she chased down Janet's bus one morning because Janet forgot the potato chips with her lunch. These days, sometimes Sarah has a dream. All four kids are at home, sitting at the kitchen table. Their dad is sitting with them. Their mom is in the kitchen making dinner. "We're looking around the table at each other," Sarah says. "She's not supposed to be here. She's dead. But we don't say anything. Because we don't want her to go away."

Inescapable images

These pictures belong in the album, too. Nobody wants them there but they are glued to the pages. Elias Syriani beat his wife. Police were called to the house 10 times in two years. Teresa told neighbors that Elias hit her with a table leg. Once he went after her with a baseball bat. She got a restraining order and he was forced to leave their southwest Charlotte home. She filed for divorce. On a summer night in 1990 she drove home from her job at a convenience-store deli. John was with her. He was 10.

A block from home, Elias blocked her car with his van. He took the screwdriver in his hand and reached in through her door. The car shook. John tried to push his father away. Then he ran home and told Rose to call the police. Witnesses said Elias attacked Teresa, went back to his van, then started walking back toward the car. He left only when he saw a neighbor heading toward him. Teresa died after 26 days in a coma. By then the kids were living with their aunts. And Sarah was cutting her father's face out of the family photos.

Raising and lifting each other

Look at this picture, just a few days ago, the kids in their Raleigh hotel room -- joking, finishing one another's stories, arguing about who's the best Ping-Pong player.Their aunts raised them, but just as much, they raised one another. Janet remembers winning a school award in eighth grade and needing to bring a parent for dinner with the principal. She went to her oldest sister and said: Rose, you've got to be my mama tonight.

Janet's 23 now and studies accounting. John's 25 and sells Hondas at a car dealership outside Chicago. Sarah's 27 and lives with her husband near San Francisco. Rose, who's 29, just got a job doing consumer research in the same part of the country; she's moving in with Sarah until she finds a place of her own.

They try to explain how they came to forgive their father for what happened 15 years ago. They say it's a miracle. They say it's their mother watching over them, telling them it's OK. Every so often they just shrug. They don't have the words. It happened so fast last summer. The four of them decided to visit their father together. Sarah was about to get married and wanted to see if she could cleanse her heart. Rose wanted to show her father how far she had made it without him.

They had read a report prepared for his court appeals. It told them things they had never known. It told how Elias had grown up poor near Jerusalem, how his father had been sent to prison and exiled to Jordan, how the family was torn up with anger and guilt. They felt sorry for him. They did not yet forgive. But they got to the prison and he smiled at them behind the glass and their hate fell away. "I don't quite know how to say this," Rose says. "None of this justifies what he did. There is no way to justify it. "But now we're able to pick up these wonderful pieces of our lives, these things we had put away. It's not our fault any of this happened. We just have to find out a way to live. "Our mom and dad did love each other. And the love they had together -- " Sarah breaks in: " -- created us." "Yes. Created us."

A talk with the governor

There's no chance that Elias Syriani will be freed. His best hope is life without parole. Clemency from the governor is his main chance at escaping execution. North Carolina has no clemency board; Gov. Easley makes the decision on his own. The hearing was Thursday at the Capitol. Normally, Easley focuses on the legal arguments in the case. So the Syriani kids weren't scheduled to talk with him; instead they had a meeting with his chief legal counsel, Reuben Young. The kids showed up early, just in case. The hearings are closed to the public. Mecklenburg County and state prosecutors spoke to Easley first. (They wouldn't comment on what they said in the hearing.) Henderson Hill, Elias Syriani's lawyer, went next. He said he made the case he has made through years of appeals: that the jury didn't get to hear about the hard life Syriani had growing up, or about possible evidence of mental illness.

As Easley listened to the legal arguments in his office, the kids spoke to Young in a room on the other side of the hallway. They finished. They waited. Then they were asked to come across the hall. The governor showed them pictures of his children. Rose and Sarah did most of the talking. They told the governor that they lost the most when their mother died. But now they have their father back, and they have the most to lose again. Easley usually waits until the final hours to decide on clemency. Since he took office, he has stopped executions twice. Twenty-one times he has let them proceed.

Later Thursday, about 12 hours after he spoke to the kids, Easley denied clemency in the case of Steven Van McHone. McHone died by lethal injection Friday morning.

There is a videotape of John and Janet's christening. The images on the screen are the only moving pictures the family has left. The kids tried to watch 10 years ago but they couldn't take it. Then the tape went into evidence at their father's trial. Finally, two weeks ago, they watched. The tape shows a party that the Syrianis had in their yard. Dozens of people came. Elias -- who sang on the radio back in Jordan -- is singing in Arabic: This life that I'm living is a beautiful life. Teresa comes up and wraps her arms around him, runs her fingers through his hair, wipes the sweat from his face. All around them, children dance.

For years the Syriani children cut their father out. Now, at the end, he is back in the picture. They don't know if you can understand. Sometimes they don't understand. But this is what they have. Memories, an old blurry tape, some photos on the side of a bag.

Snapshots.

You take the snapshots, and you arrange them a certain way. And out of that you try to make a life.

Elias Syriani From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Elias Hanna Syriani (January 7, 1938 – November 18, 2005) was a convicted murderer executed by the U.S. state of North Carolina by lethal injection. He was convicted of the July 28, 1990 murder of his wife, Teresa Yousef Syriani, in Charlotte, North Carolina. At 67, he was one of the oldest people executed in the United States since 1976. He was also one of the people used by Benetton in their anti-death penalty advertising.

Youth and marriage

Syriani was born in Jerusalem, which at the time was part of the British Mandate of Palestine, into an Assyrian Christian family.[1]

When he was 12 his father developed cancer, forcing Syriani, the eldest son, to leave school and go to work. The family moved to Amman, Jordan, where he worked as a machinist. After working in the Jordanian Army for nine years, he left and worked as a machinist for a company in Jordan and also for a radio station, singing in Arabic. In the mid-1970s he decided that he was now financially able to marry. He met Teresa through a mutual friend. She had emigrated to the United States and they exchanged letters and photographs for about three months. She returned to Jordan only two or three weeks before the wedding.

They then moved to the United States, living in Chicago, Illinois, where Teresa lived and dressed according to Middle Eastern tradition. But after moving in 1986 to Charlotte, North Carolina, she took a job at a gas station, dressed in a more American fashion and made friends. Syriani disapproved and the two argued over it.

Crime

Teresa had received a protective order from a North Carolina court requiring that Syriani move out of their home and stay away from her and their four children. Around 11:20 p.m. on July 28, 1990, he drove to the house and found that Teresa was not home so he waited in the driveway. When she returned from work, he blocked her access with his van. After getting out of the van he went over to the car where, through an open window, he stabbed Teresa 28 times with a screwdriver, with their 10-year-old son, John, in the passenger seat. John tried to stop his father but was unable.

John ran from the car and summoned help from his older sister, Rose. He then went to a friend's house and on returning they found Syriani still at the car and still stabbing Teresa. She was still alive, and Syriani stopped his attack, got into his van and left. He drove to a nearby fire station to receive medical attention for cuts and scratches. A fireman testified that Syriani told him that Teresa had assaulted him. The police arrived shortly afterwards and arrested him.

Teresa survived for 28 days before succumbing to a 3-inch (80-mm) deep wound in her brain. One neighbour who saw her in the car said that it looked like she had been shot in the face with buckshot.

Syriani gives a different version of events, testifying at his trial that he did not block Teresa's path, nor did he intend to hurt or kill her on the night. He said that she scratched at his face when he approached the car and then slammed the car door open onto his leg. He claims to only remember striking her three or four times with the screwdriver.

Trial and appeals

Before Teresa's death, Syriani was charged with assault with a deadly weapon with intent to kill. This charge was changed to capital murder after her death. On June 12, 1991 he was sentenced to death in Mecklenburg County Superior Court, with the jury finding as an aggravating factor the crime being especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel. This outweighed the eight mitigating circumstances they also found.

Syriani testified that his wife had hit him almost every day in front of their children and had called the police about him several times. He did admit to hitting her three or four times during their first five years of marriage. The children contradicted him, saying that the marriage was full of instances of domestic violence from both sides. Their middle daughter, Sara, testified in the penalty phase of the trial that during one argument Syriani chased after Teresa with a pair of scissors, in another instance back-handed her while they were in the car and one time threw her down the stairs by her hair. John said that another time, his father threatened Teresa with a bat.

Syriani petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus, arguing that his trial counsel was ineffective and denied him a fair trial. His children said they had forgiven their father and asked that his sentence be commuted. An appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States was denied in October 2005 and the execution date subsequently set for November 18, 2005.

An appeal for clemency was denied by Governor Mike Easley on November 17.

Execution

Syriani was pronounced dead at 2:12 a.m. on November 18, 2005 at the Central Prison. None of his children witnessed the execution, though they did meet him during the previous day, leaving about 11 p.m..

In his final statement he said: "I want to thank God first for everything that happened in my life. I want to thank my children. I want to thank my family, especially my sister, Odeet. I want to thank all the beautiful friends who share with me my sufferings for 15 years and four months and they so encouraged me, specifically Mr. and Mrs. Meg Eggleston who become a sister to me. She helped me a lot to accept everything. I thank everyone from the staff, nurses, chaplains. I thank everyone."

It was the 997th execution in the United States since the Gregg v. Georgia decision.

"NC governor denies clemency for Elias Syriani in wife's killing," by Estes Thompson. (AP November 17. 2005) 9:10PM

Gov. Mike Easley denied clemency Thursday for Elias Syriani, the Charlotte man condemned to death for the 1990 stabbing death of his wife. The decision came despite pleas from the Syriani children, who had asked the governor and prosecutors to spare their father's life so they could forge a relationship with him and restore family memories that were severed by the killing. "After careful review of the facts and circumstances of this crime and conviction, I find no convincing reason to grant clemency and overturn the unanimous jury verdict affirmed by the state and federal courts," Easley said in a statement.

Syriani, 67, was scheduled to die at 2 a.m. Friday by injection at Central Prison in Raleigh. The children - three daughters and a son, who witnessed the attack in the family car - began visiting with their father at the prison Thursday morning. They left him shortly before 9 p.m. and the daughters were sobbing. Thursday's visit was the first time the children had been able to touch their father in 15 years, said Russ Sizemore, an attorney for the children. "The contact visit, literally, that's the first contact they've had with their father in 15 years, touching," said Russ Sizemore, an attorney for the children.

Sizemore said Easley's decision not to grant clemency was inexplicable. to He said he gave research to the governor showing that clemency would help the family heal from the domestic violence. "It had greater depth and implications than just a sob story for four people," Sizemore said. "They've traveled such a long distance that it is just inexplicable in some ways to have the journey end this way."

Syriani did not request a last meal, said Pam Walker, spokeswoman for the state Correction Department.

The children, all of whom live out of state, had been vocal public advocates for clemency, but grew more private as the execution day approached and inmate Steven Van McHone was put to death ahead of their father. McHone's execution brought the reality of the death chamber home to them, Sizemore said.

Easley has granted clemency twice since taking office in 2001, but has not spared the life of any death row inmate since January 2002. North Carolina governors have granted clemency only three other times since the state resumed executions in 1984 after a hiatus while the U.S. Supreme Court determined its constitutionality. Nationally, clemency was granted 186 times - including 167 commutations by the Illinois governor in 2003 - between 2001 and 2005, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Syriani was convicted in the death of his wife, Teresa Syriani, 40, who was stabbed 28 times with a screwdriver in Charlotte. She died 26 days later from the attack that started when she told her husband as they drove home that she wanted a divorce. The couple was separated and she had gotten a restraining order against him.

Syriani's lawyer, Henderson Hill, said he dropped all legal action in the case, pursuing clemency. Prosecutors, who also have talked to the children, refused after meeting with Easley to say whether they favored execution.

The Syrianis hadn't seen their father on death row until two years ago and have since said they have forgiven him. Part of their forgiveness stems from learning about his traumatic upbringing as an Assyrian Christian in Jerusalem.

"Governor is killer's only hope; With no appeals filed, Elias Syriani's children seek commutation for the man who killed their mother; Syriani is to be executed Friday," by Andrea Weigl. (November 17, 2005)

The children of Elias Syriani had to reconcile with their murdering father to reconnect with memories of their mother, whom he killed 15 years ago. Now, Gov. Mike Easley is their only hope of not losing that newfound connection to their mother. Syriani, 67, is scheduled to be executed at 2 a.m. Friday at Raleigh's Central Prison. Syriani's appellate lawyers decided not to file any last-minute appeals seeking a stay from the courts. Therefore, Syriani's sole chance to escape lethal injection rests with Easley.

At the time of the killing, the couple lived in Charlotte with their four children, who are all asking that their father's death sentence be commuted. The governor met last week with the Syriani children -- Rose, Sarah, John and Janet, all now in their 20s.

Syriani was sentenced to death for stabbing his wife, Teresa, more than 25 times with a screwdriver. Their son, John, 10 years old at the time, witnessed the attack. All of the children lived with the escalating domestic violence in the family's home before the killing. Last year, they all reconciled with their father and have since reveled in the memories of their mother that writing to and visiting with their father have restored.

"In this case, it is the kids' healing that's the issue," said Charlotte lawyer Russell Sizemore, who represents the four siblings. "It's the children of domestic violence saying, 'We have a chance to recover our lives; please don't stop that healing process.' "

Elias Hanna Syriani, 67, was scheduled to be executed Nov. 18 for the 1990 murder of Teresa Yousef Syriani in Mecklenburg County. Fifteen years ago, the four Syriani children - Rose, Sarah, John and Janet -- lost their mother. Now, they are just weeks away from losing their father: 67-year-old Elias Syriani, who is scheduled to be executed next month for the July 1990 murder of his wife and the mother of his children, Teresa and they are pleading with Gov. Mike Easley to save their father's life. "We're just begging that this does not get carried out," daughter Rose Syriani said during a press conference at the Legislature on Tuesday. "This is four lives that will be destroyed."

Teresa Syriani was stabbed 28 times with a screwdriver as she sat in her car with her son, John, in Charlotte, police said. Three of the children testified against their father either during the guilt or penalty phase of the trial. After more than a decade of estrangement, the children, who are now adults, met with their father at Central Prison in August 2004. "I've always thought of him as a murderer that took my mom. But when I saw him for the first time waving and smiling like a kid in Disneyland, I saw my dad," daughter Sarah Barbari said. Over the past year, the children have developed a new relationship with their father. All four children said their change from anger and bitterness to forgiveness and love is a "miracle" they believe is the work of God and their mother.

The U.S. Supreme Court and Easley will look at the law surrounding the case. Defense attorneys, who have lost their appeals in lower courts, claim Elias Syriani did not have a competent attorney at trial. Syriani's attorneys said they have one more appeal to file with the courts. On Nov. 8, they also plan to meet with Easley during a clemency hearing in which they will ask the governor to stop the execution. Syriani is scheduled to be executed at Central Prison on Nov. 18.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Elias Hanna Syriani faces execution in North Carolina Nov. 18 for the July 28, 1990 murder of his wife in Mecklenburg County. Syriani and his wife had recently separated. Witnesses at Syriana’s trial disagreed with each other regarding whether his marriage was a violent one.

The murder weapon, a screwdriver, was never found. Two witnesses testified that, while he was seeking treatment for wounds to his face and leg, Syriani claimed that his wife assaulted him the evening of the murder. A number of witnesses close to, or familiar with, Syriani and his family testified that he was an honest, hospitable, mild-mannered man who was head of a loving and happy family.

Trial counsel failed to present mitigating evidence of Syriani’s harsh upbringing in a poor and abusive household in Palestine and Jordan. When Syriani was 12 years old his village was annexed by Israel and his father was among the men held indefinitely in a camp. More than a year later his father returned, but was not the same. After his trial, a psychiatrist claimed that Syriani was suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder at the time of the crime.

The defendant expressed his sorrow and remorse for the crime. He presented evidence at trial that he had been well-behaved in jail. He also suggested that he was under emotional and mental distress at the time of the crimes because he feared losing his wife and children. Syriani is now 67 years old.

Please write Gov. Michael Easley requested that Elias Hanna Syriani’s sentence be commuted to life in prison.

People of Faith against the Death Penalty

A Family's Journey Through Tragedy to Forgiveness

Elias Syriani was sentenced to death in Mecklenburg County for the 1990 murder of his wife, Teresa. The State of North Carolina has scheduled Elias Syriani's execution for November 18, 2005. Today, the living victims of this crime, Elias and Teresa's adult children—Rose, Sarah, John and Janet—urgently plead for their father's life to be spared.

Rose, Sarah, John and Janet Syriani were children when their father murdered their mother. Their lives were torn apart by their father's actions and they were left to raise themselves, burdened with loss, hate and confusion. Nevertheless, two years ago, after a decade of silence, they felt a need to confront this man who had caused them so much pain. In a remarkable encounter at Central Prison, Rose, Sarah, John and Janet experienced the beginnings of a healing process that continues to this day. They say the courage to confront and ultimately forgive their father came from their mother, Teresa. They found a different man than they expected, and they have been transformed as well, by learning of his sorrow, his love for them, and the power of their forgiveness. This transformation is not yet over.

Teresa Syriani's children understand more powerfully than anyone the loss and pain their father caused. Yet for Rose, Sarah, John and Janet, the arc of healing from their terrible loss now bends toward forgiveness, and a new relationship with their father and newly recovered memories of their mother. That healing is now threatened by another hurtful final loss. Here the death sentence will inflict a new wound on those who have already suffered from the crime. Recently speaking out against her father's death sentence, Sarah pleaded for mercy, for her father, and for her siblings, saying, “We've suffered enough.”

Please support Rose, Sarah, John and Janet Syriani's efforts, by asking Governor Easley to grant clemency for Elias Syriani.

State v. Syriani, 333 N.C. 350, 428 S.E.2d 118 (N.C. 1993) (Direct Appeal).

Following jury trial before the Superior Court, Mecklenburg County, Robert M. Burroughs, J., defendant was found guilty of first-degree murder of his wife and sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, Whichard, J., held that: (1) excusing prospective juror for cause because of his views on death penalty did not deny defendant's constitutional rights; (2) children's testimony regarding defendant's specific instances of prior misconduct toward them and their mother was properly admitted to show motive, opportunity, intent, preparation in absence of mistake or accident; (3) cross-examination of defendant with regard to both specific and general misconduct toward his wife was proper; (4) state was properly permitted to question defendant's character witnesses regarding specific acts of misconduct by defendant; (5) color photographs of victim's body were properly admitted to illustrate testimony; (6) evidence was sufficient to sustain conviction of first-degree murder; (7) aggravating circumstance that murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel, was properly submitted, instructions were not too vague, and evidence supported determination of existence of circumstance; (8) defendant's testimony alone that his judgment was affected by emotional disturbance did not support reasonable inference that defendant's capacity to appreciate criminality of his conduct was impaired, lessened or diminished such as to require submission that mitigating circumstance; and (9) imposition of death penalty was not disproportionate. No error.

WHICHARD, Justice.

Defendant was tried on an indictment charging him with the first-degree murder of his wife, Teresa Yousef Syriani. The jury returned a verdict finding defendant guilty upon the theory of premeditation and deliberation. Following a sentencing proceeding pursuant to N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000, the jury recommended that defendant be sentenced to death. For the reasons discussed herein, we conclude that the jury selection, guilt, and sentencing phases of defendant's trial were free from prejudicial error, and that the sentence of death is not disproportionate.

State's evidence tended to show the following: Defendant and his wife were living apart, defendant in a motel, and his wife with their children in their home. On 28 July 1990, around 11:20 p.m., defendant drove to their home, but his wife had not returned from work. As she drove her automobile onto a nearby street, defendant blocked her way with his van. Defendant got out of his van, gestured, and chased after her car as she put it in reverse. As his wife sat in her car, defendant began stabbing her with a screwdriver through the open door or window, while their ten-year-old son John sat in the seat beside her. John was unable to stop his father; he got out of the car and ran home to get his older sister. At least two neighbors watched from their homes as defendant stabbed his wife and then walked away. Teresa Syriani died twenty-eight days later due to a lethal wound to her brain.

David Wilson testified that he lived in the Syrianis' neighborhood. He knew defendant's son but only knew defendant by sight. On 28 July 1990, around 11:20 p.m., Wilson was at home when he heard children hollering. He looked out his window and saw a van parked across the street with the interior lights on and the door open. He looked again and watched defendant come toward the van, get into the driver's seat, and fumble with something. Then he saw defendant go back down the street and cross the street to a car in the driveway of the house next to Wilson's. Defendant leaned over inside the car. Wilson saw the car shaking. Then Wilson went outside, whereupon he saw defendant back in the van. He also saw two young boys, John Syriani and John's friend. Wilson heard a young woman hollering "somebody help my mother" and went to the car. A woman in the car was covered in blood. A neighbor wiped her face. She looked to him "like somebody [who] had been shot in the face with a load of buckshot."

Thomas O'Connor testified that he lived near the Syrianis but did not know them. On 28 July 1990, around 11:20 p.m., he received a phone call from a neighbor prompting him to look out his window. O'Connor saw a man standing at a car halfway in a driveway holding what appeared to be a screwdriver and "stabbing into the car." O'Connor ran outside, yelling, and made eye contact with the man. The man kept stabbing into the car. O'Connor ran back inside to phone the police, then ran outside. He saw the van pulling away. The van stopped and the man, screwdriver in hand, got out and walked toward the car. The man saw O'Connor, turned back to the van, and drove away.

Defendant's eleven-year-old son, John, testified that the family had lived in the house in Charlotte since 1986 except for a week in the summer of 1988 when the police took him, his sisters, and his mother to a Battered Women's Shelter. Then they stayed with his mother's sister in New Jersey for about a month. When defendant came to take them back, they returned to Charlotte. In July 1990 he, his three sisters, and his mother lived in a motel. They moved back to their home when defendant moved out.

28 July 1990, John went with his mother to the Crown gas station. His father came by and asked him to go out with him. John rode home with his mother and saw his father's van stopped ahead as they approached their home. As his mother approached the turn onto the main street before their house, defendant moved the van to block her way. Then defendant got out of the van, gestured, and chased the mother's car. She put the car in reverse. Defendant opened the door and started stabbing John's mother, who started screaming. John tried to push his father's hands off her, but he could not stop his father. John ran home to get his older sister and told her, "Dad is killing Mom." John then ran to his friend's house. John and his friend ran back to his mother's car, now in a neighbor's driveway. Defendant was kneeling at the open door, stabbing into the car. Defendant then walked back to the van and yelled, "Go home bastard," in Arabic, to John. Frightened, John ran back down the street. Neighbors took John into their home.

On cross-examination, John testified that his father worked long hours. His father always carried a screwdriver as part of his work tools. His mother had never worked, had dressed according to Arabic tradition, and had worn no makeup or lipstick before they moved to Charlotte. His parents had argued, but mostly over the children. In 1988 or 1989, John's mother decided she did not like staying at home and wanted to get a job. At her second job at a gas station, she worked some nights. When his mother worked nights, his older sister babysat. Starting in 1990, his parents argued more frequently. Defendant did not like the fact that John's mother was working; he wanted her to stay home with the children. In July 1990, defendant moved into a motel.

When he first spotted the van the night of 28 July 1990, John thought the motor was turned off because the headlights were turned off. Defendant, however, turned on the headlights and turned his van to the right across the street. Defendant had stabbed John's mother once before the car came to a complete stop in a driveway. On redirect examination, John recalled seeing his father slap his mother when he was five and hit his mother in "the ear" on Easter Sunday, 1989. John also recalled seeing his mother "screaming and running out of the house" while his father stood at the door in the summer of 1988. Finally, John testified that his mother was a good mother. She and his father argued about three times a week, and his father called her names, for example, "whore."

Defendant's eldest daughter, Rose, testified about the events leading up to the stay at the Battered Women's Shelter in the summer of 1988. Rose and her mother were at home when defendant came in and threw the groceries at them. Defendant started to scream at his wife, jumping up and down and breaking a table with his foot. Then defendant went into the garage and returned with a large wooden bat. He ran upstairs after her mother, who had left the house. The police showed up shortly thereafter and took the mother and children to the shelter. Contrary to John's testimony, Rose testified that her parents fought constantly in Illinois. In the summer of 1990, her mother was sleeping in the younger daughter's bedroom. In July, they moved to a motel.

28 July 1990, John came to the front door banging and screaming, "Dad is trying to kill Mom." Rose called the police, saw her brother coming back, and ran to her mother. She saw her father enter his van, look at her, and drive away. When she reached her mother, her mother said, "Ma Ma, shut up." "Ma Ma" is Arabic for "honey."

On cross-examination, Rose maintained that her parents were always arguing and defendant would jump and yell at her mother, although there were times when her parents did not argue. Sometimes her father "would go downstairs around three o'clock in the morning ... and just start breaking things downstairs." During arguments between January and July 1990, her mother would say she would quit her job if defendant would buy food the children liked to eat. Rose also testified about the time defendant started yelling at her in Arabic and grabbed her around her throat, saying he was going to kill her. Rose remained angry with her father in 1988, 1989, and 1990 because he constantly disciplined the children--for example, they were not allowed to play outside after 5:00 p.m.--and he argued with her mother.

On redirect, Rose testified that her mother told her to "shut up" because she was screaming, holding her mother's hand, trying to sit her mother up, and shaking her to see if she were still alive. Once her mother spoke, she stopped shaking her and went for help. Rose then testified about a number of specific instances of verbal and physical abuse by her father. When defendant thought she had scratched his new van, he grabbed her and started to kick her. Crying, she ran out of the house. She testified: "[H]e got me on the floor and kicked me ... into the ground. People were walking by and my mom pulled his leg off me." Defendant told her mother he would kill her if she ever left him, that she would not live without him, and that he would "f--- up our world."

On recross-examination, Rose testified that the children were always scared of their father even though he provided well for them. Jeane Allen, a registered nurse at the Carolinas Medical Center, testified that she saw Mrs. Syriani at 12:24 a.m. on 29 July 1990. The victim was covered in blood and suffered from lacerations to her arm, right side, and face. As she was being moved, she grasped her jaw and complained, "It hurts." Monitors showed she had difficulty breathing, so someone inserted a tube through her nose into her lungs to facilitate breathing. On cross-examination, Allen testified that the cuts below the victim's temple area were superficial but the ones above were not.

Kenneth C. Martin, an attorney, testified that the victim had asked Martin to represent her in a domestic action against defendant in November, 1989. He prepared a complaint against her husband, but she only decided to file it on 27 June 1990. An ex parte domestic violence order was issued on 5 July 1990. Alice Safar, the victim's older sister, testified that she visited her sister at the hospital on 29 July 1990. Mrs. Syriani squeezed her hand when Safar spoke to her. On cross-examination, Safar testified that the marriage between her sister and defendant had been arranged.

James Sullivan, a forensic pathologist and medical examiner, testified that he performed an autopsy on the victim's body on 24 August 1990. Seven healed wounds were located on her left cheek, five wounds on the left side of her neck, five wounds on her right cheek and around her mouth, and five wounds to the back of her right hand and arm. There were visible healed wounds in the mouth where the victim's jaw had been fractured, and several of her teeth had been fractured or lost. Several of the wounds had been sutured. All of the wounds had a linear or rectangular configuration.

However, in Sullivan's opinion, the chronic penetrating brain wound caused the victim's death. A three-inch deep puncture wound to the right temple, to the right of her right eye, penetrated the victim's brain, going through the right temporal lobe and into the deep central area of her brain known as the basal ganglia area. Such a wound would cause brain dysfunction, unconsciousness or coma, infarct or stroke, and paralysis on the left side of her body. There was a small rectangular defect in the approximately one-eighth-inch-thick bone. The wound was caused by a narrow instrument like a squared-off pick, screwdriver, or knife. Sullivan opined that it would take a substantial amount of force to penetrate an adult's skull. On cross-examination, Sullivan testified that none of the arm or hand wounds were life threatening.

Charlotte Police Department Investigator Hilda M. Griffin testified she arrived at the scene around 11:37 p.m. She found the victim alive, sitting in the car with her head laid back. Blood was everywhere. Mrs. Syriani tried to speak, but Griffin could not tell what she was saying. When Griffin arrived at the fire station where defendant had stopped for first aid, defendant had already been arrested, and his van had been searched. He appeared sober. There was blood all over him, but only some light scratches on his arm and shoulder. Griffin testified that a team searched for, but never found, the murder weapon.

Dr. Richard C. Stuntz, Jr., the first witness for the defendant, testified that on the morning of 29 July 1990, he treated defendant in the emergency room of Carolinas Medical Center. Defendant's hand was bruised. There was an abrasion on his lower left leg, and there were scratches on his nose and shoulder which could have been caused by a fingernail. His hand was X-rayed, and he was treated with a tetanus shot and pain medicines. On cross-examination by the prosecutor, Stuntz testified that defendant told him he had been assaulted by his wife.

Charles M. Stanford, a fireman, testified that around 1:00 a.m. on 29 July 1990 defendant walked into his station. Stanford tended to scratches on defendant's face, arms, and chest. Defendant told him he had been in a fight. On cross-examination, Stanford testified that defendant said his wife had assaulted him. Walid Bouhussein testified that he lived two or three blocks from the Syrianis and had known them almost three-and-one-half years. Their families exchanged visits and ate together a number of times. He had never seen any arguments between defendant and his wife. His children felt "a warmth" toward the defendant. Both defendant and his wife were very nice people, neither appearing violent nor showing temper. Defendant was very hospitable, a "mild-mannered man." On cross-examination, Bouhussein admitted that Mrs. Syriani had told his wife that defendant mistreated her.

On redirect, Bouhussein testified that defendant was known in the community as a very hard-working, mild-mannered man. He did not have a reputation for violence, but he did have a reputation for truth and veracity. Upon recross-examination, the prosecutor questioned Bouhussein about specific instances of defendant's misconduct toward his wife and children. Michael Carr, a domestic law attorney, testified that he had talked with defendant about the ex parte domestic violence order. At the 12 July 1990 hearing defendant and his wife agreed to joint counseling, but a few days later Mrs. Syriani changed her mind and no longer wanted it. Carr testified that defendant had wanted very much to be reconciled with his wife.

David D. Stevens testified that he first met defendant in 1983 when they worked at Kerr Glass in Chicago. Defendant was a good worker. When Kerr Glass closed, Stevens moved to Charlotte, became a supervisor at Midland Machine Corporation, and hired defendant. During the time he knew them, he never noticed a problem between the Syrianis. The children did not appear to be afraid of their father. Further, defendant never argued with, abused, or fought with any fellow employees. On cross-examination, however, Stevens conceded that he had told defendant's current boss not to hire defendant because he had a "terrible temper and the men were afraid of him."

Harold Linn testified that he had been a plant superintendent with Protective Door Manufacturing Company and had met defendant in 1977. Defendant was looking for work, and Linn hired him. Linn considered defendant a terrific employee, one of the hardest workers at the plant, capable of "great, beautiful production." Even after Linn retired and moved to North Carolina, he maintained contact with the Syriani family. He was very close to defendant. He respected him very much as a man who had earned everything for himself, having come to this country with only a few dollars in his pocket. Linn also testified that there seemed to be a great deal of love in the Syriani household, and the Syriani children always seemed to enjoy having the Linns visit. They were "bright kids, very well trained. You couldn't ask for a better family." The prosecutor cross-examined Linn with regard to specific acts of misconduct by defendant toward his wife and children. Linn replied that he could not believe any of those things occurred, that it was not in defendant's nature, and that all he ever saw was that defendant had "good and deep family devotion, the kind that most of us would envy."

Florence Linn, Harold Linn's wife, testified that when the Linns visited the Syriani home they never observed discord or arguments. She never noticed abusive conduct by defendant toward his wife or children, only "loving conduct." She thought a better family atmosphere could not have been asked for, and that the children were bright, healthy, and well-loved.

Odett Syriani, defendant's older sister, testified that the Syriani children now live with her in Illinois. Her brother's marriage had been arranged. Teresa Syriani, the victim, had been living in New Jersey. Teresa and Odett's brother were married in Jordan, and he followed his wife back to the United States. Odett visited the family for six months in 1987, and later the family visited Odett in Chicago. She did not notice any problems between defendant and his wife. They seemed to get along very well together.

Defendant testified on his own behalf. Born in Jerusalem in 1938, he had to leave school at age twelve when his father, a laborer, became sick. He worked to help his mother support his three sisters and two brothers. He learned the machinist trade. He entered the Jordanian Army at age nineteen as a civilian machinist. His sisters did not work because "their job was to finish school, then they engage and then they get married." After leaving the army, he worked in a garage and then as a singer on a radio station. At the age of thirty-six he married Teresa in Amman, Jordan. She was twenty-four. Friends had arranged the marriage. She returned to the United States, and he followed. They lived in Washington, D.C., where he worked as a busboy and learned English at night. They then moved to Chicago, where defendant found work as a machinist with Protective Door.

When Protective Door closed some six years later, defendant went to work for Kerr Glass Manufacturing, where he stayed almost six years. Although Mrs. Syriani had worked at Woolworth's, she had stayed at home after the birth of Rose, their first child. Defendant purchased a home for his family in Calumet, Illinois, near Chicago. When Kerr Glass closed in 1986, defendant moved to North Carolina, found a job and a place to live, and brought his family to Charlotte. While in Chicago, he and his wife rarely argued. When they did, it was nothing of a serious nature. They spoke Arabic in their home. Whenever he was away, he called the family every night, and they missed him very much. In Charlotte, Mrs. Syriani asked if she could take a part-time job. He bought another car for her use. Her first job was in a restaurant, but she quit and found work at a local service station. After she began working, she changed "fast[,] very fast." Although he loved his wife, he was not happy with the change. Despite the problems caused by his wife's deviation from Arabic tradition, defendant did not strike his wife. Rather, he tried to make her "more happy."

Defendant recalled receiving papers from a lawyer about his wife's request for a divorce. In July 1990, she came home with police officers and told defendant he had to leave his keys and move out of the home. Defendant packed his clothes and moved into a hotel room. Defendant visited the neighborhood several times. He saw John skateboarding outside and asked John to tell his mother he wanted to talk with her. John did not respond. Another time, defendant asked John to ask his mother for the small television because he did not have one in his hotel room. Mrs. Syriani refused his request.

On 27 July 1990, defendant worked his normal half day. Late that evening, he saw his son outside the gas station. He asked John whether he could go to lunch with him the next day. Mrs. Syriani said John could not go with his father. On 28 July 1990, defendant went to the gas station and asked whether John could go out to lunch, but Mrs. Syriani refused to let the child go. Defendant returned to his motel room. Around 8:00 p.m., he went to the supermarket near the gas station. He did not see his wife's car pass by and believed that his wife was still working at 11:00 p.m. Concerned about the family's safety, he left the supermarket and went to their home, but his wife was not there. On his way to the gas station to ascertain why his wife was late in coming home, he saw her car. She stopped her car, and he went up to ask about his children and who was supervising them. She scratched his face, and he pushed her away. She opened the driver's side door, hitting him in the leg. He grabbed the door, and she placed the car in reverse. He struck at her through the open window with a screwdriver he had in his pocket, trying to get her to stop moving the car. He never had any desire to hurt or kill his wife and remembered hitting her only three or four times. He loved his wife very much.

On cross-examination, defendant recalled the time in 1985 when he thought his daughter Rose had scratched his new van. He did not drag her by the hair and kick her. He spanked her on the "butt." It was the first spanking he had ever given her. Defendant denied pulling hair out of his wife's head over an argument about a washing machine. He denied knocking Sara down and kicking her in the summer of 1989. She had lost her tennis shoe, and he only spanked her on the bottom. He denied ever putting his hands around Rose's throat. Defendant admitted he had hit his wife when they had lived in Illinois and had hit her on the hand while driving in the van on Easter Sunday, 1989. They had been arguing about lamps, and she had put her hand on the door as if to open it. Defendant testified that during the last three months of their marriage his wife beat him, sometimes in front of the children. On the night she told him she would leave him, she hit him and then called the police to escort her and the children away from their home. Fifty minutes later, defendant called the police and told them his wife had assaulted him but he did not want her arrested. Defendant stated that he loved his wife and children, and up until the end he hoped he and Teresa would reconcile.

Cindy Smith testified for the State on rebuttal. She lived next door to the Syrianis in Charlotte. Smith thought Mrs. Syriani was a gentle person, but her husband had a violent temper. Upon cross-examination, Smith admitted that she had never heard an argument, that the Syrianis were a discreet family and conducted their business within their home, but she could see that defendant had an incredible temper "from the fear and the terror in the children's faces and Teresa['s]." Defendant moved to dismiss at the close of the State's evidence. The trial court denied the motion. The jury found defendant guilty of first-degree murder based on premeditation and deliberation.

At the capital sentencing hearing, defendant testified that he had been out on bond for a short time, during which he had arranged for the care of his children. He testified that he felt "real, very terrible" about what had happened, that he loved his wife and missed her very much, and that he was very sorry for what he had done. He reiterated that at the time of the confrontation with his wife, he was very emotional and upset, feeling he was going to lose his wife and family. Finally, he testified that in his eleven months in jail he had never been cited for any misconduct or caused trouble for anyone.

Michael Thomas McCarn, a deputy with the Mecklenburg County Sheriff's Department, testified that during defendant's eleven months of incarceration he never gave anyone trouble, was "very cooperative," and was a model prisoner.

In rebuttal, Sara Syriani, defendant's second oldest daughter, testified for the State that on one occasion her father threatened her mother with a pair of scissors. On Easter Sunday, 1988, he hit her mother. Further, her father had yelled at her, pushed her down, and kicked her. Finally, on her graduation from sixth grade, he had yelled at the victim, followed her upstairs, grabbed her by her hair, thrown her down the stairs, and dragged her into the kitchen, ripping her shirt. Following the capital sentencing hearing, the jury found one aggravating circumstance--that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel--and eight mitigating circumstances. Among these was one statutory mitigating circumstance, that the murder was committed while defendant was under the influence of mental or emotional disturbance. The remaining nonstatutory mitigating circumstances pertain to defendant's understanding of the severity of his conduct, defendant's demonstrated ability since his incarceration to abide by lawful authority, defendant's history of good work habits, defendant's history of being a good family provider, defendant's good character or reputation in the community in which he lived, defendant's upbringing in a different culture, and defendant's aggravation by events following the issuance of the ex parte domestic violence order.

Upon finding that the mitigating circumstances were insufficient to outweigh the aggravating circumstance, and that the aggravating circumstance was sufficiently substantial to call for the death penalty, the jury recommended a sentence of death.

* * *

Defendant contends that the trial court erred in overruling his objections and allowing testimony by his children--John, Rose and Sara Syriani--about defendant's specific instances of prior misconduct toward them, contrary to Rules 404(b) and 403 of the North Carolina Rules of Evidence. John Syriani, age eleven, testified for the State. During cross-examination, John responded to many questions about how well his parents got along. John testified that his father was a giving person and his parents got along, but sometimes they argued. Beginning in 1990, they argued more and more. In July 1990, defendant moved out of the house. During redirect examination, John testified, over objection, that when he was five, he saw his father slap his mother. Further, he frequently heard his parents arguing and heard defendant call the victim "whore." John further testified, without objection, that his parents argued a lot, his father backhanded the victim during an argument on Easter Sunday, 1989, and that in 1988, prior to the stay at the Battered Women's Shelter, John saw her screaming and running from the house while his father stood in the doorway.

Rose Syriani, age fourteen, testified on direct examination, without objection, that in Illinois her parents were constantly fighting. Sometime during the summer of 1988, she left the house with her mother and siblings and went to the Battered Women's Shelter. Rose recalled, without objection, that on the day before, defendant had entered the house, thrown down the groceries he was carrying, and started screaming at her mother. Jumping up and down, defendant broke a table with his foot and called her and her mother "nasty" names. Defendant left the house but returned with a big wooden bat, with which he threatened them, trying to scare them. Rose got in front of her mother, trying to keep her father away from her mother. "[A]nd he was over me with a bat trying, you know, trying to scare us." Rose recalled that defendant later chased her mother out of the house with the bat.

During cross-examination, Rose testified that her parents would always get into bad arguments, that defendant would jump at her mother, start screaming for no reason, slam doors and break tables. In the six months before her mother's death, her parents argued about her mother's working. Then defense counsel asked Rose, "Has he ever beat you?" She replied affirmatively. While living in Charlotte, he started yelling at her, grabbed her by the throat, and said he was going to kill her.

During redirect examination, Rose testified, over objection, that defendant had also grabbed her by the hair and kicked her sometime two or so years before. Also over objection, Rose testified that defendant told her mother he would kill her if she ever left him. "He told her that she would not live without him. She wouldn't live at all." Finally, Rose recalled, over objection, that shortly before killing her mother, defendant had said that if her mother ever left him he would mess up the children's world.

Defendant contends that the evidence of specific instances of misconduct toward his wife and children was elicited from his children only to prove defendant's character, to show that he acted in conformity therewith, or alternatively, that the incidents were too remote in time, some more than two years prior to the killing, or insufficiently similar in nature to defendant's assault on their mother, to be admissible. See State v. Artis, 325 N.C. 278, 299, 384 S.E.2d 470, 481 (1989) (use of evidence under Rule 404(b) is guided by two constraints, similarity and temporal proximity), sentence vacated, 494 U.S. 1023, 110 S.Ct. 1466, 108 L.Ed.2d 604 (1990), on remand, 329 N.C. 679, 406 S.E.2d 827 (1991). Defendant failed to object to the testimony about several incidents, and our review of that testimony is limited to consideration of whether its admission constituted plain error.

We conclude that the testimony about defendant's misconduct toward his wife was proper under Rule 404(b) to prove motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, absence of mistake or accident with regard to the subsequent fatal attack upon her. Rule 404(b) provides that while "[e]vidence of other crimes, wrongs, or acts is not admissible to prove the character of a person in order to show that he acted in conformity therewith," such evidence "may ... be admissible for other purposes, such as proof of motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, plan, knowledge, identity, or absence of mistake, entrapment or accident." N.C.G.S. § 8C-1, Rule 404(b) (1992).

"Rule 404(b) state[s] a clear general rule of inclusion of relevant evidence of other crimes, wrongs or acts by a defendant, subject to but one exception requiring its exclusion if its only probative value is to show that the defendant has the propensity or disposition to commit an offense of the nature of the crime charged."

* * *

The trial court submitted one aggravating circumstance, that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel, N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(e)(9) (1988), and two statutory mitigating circumstances, that the defendant had no significant history of prior criminal activity, N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(f)(1) (1988), and that the capital felony was committed while the defendant was under the influence of mental or emotional disturbance, N.C.G.S. § 15A-2000(f)(2) (1988). Further, the trial court submitted the eight requested non-statutory mitigating circumstances, as follows: the defendant understands the severity of his conduct; the defendant has demonstrated remorse; the defendant, since his incarceration, has demonstrated an ability to abide by lawful authority; the defendant has a history of good work habits; the defendant has a history of being a good family provider; the defendant has been a person of good character or reputation in the community in which he lived; and any circumstance or circumstances arising from the evidence which the jury finds to have mitigating value.

* * *

In conducting proportionality review, we "determine whether the death sentence in this case is excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering the crime and the defendant." Brown, 315 N.C. at 70, 337 S.E.2d at 829. We compare similar cases in a pool consisting of all cases arising since the effective date of our capital punishment statute, 1 June 1977, which have been tried as capital cases and reviewed on direct appeal by this Court and in which the jury recommended death or life imprisonment or in which the trial court imposed life imprisonment after the jury's failure to agree upon a sentencing recommendation within a reasonable period of time. State v. Williams, 308 N.C. 47, 79, 301 S.E.2d 335, 355, cert. denied, 464 U.S. 865, 104 S.Ct. 202, 78 L.Ed.2d 177, reh'g denied, 464 U.S. 1004, 104 S.Ct. 518, 78 L.Ed.2d 704 (1983). This pool includes only those cases found to be free of error in both phases of the trial. State v. Jackson, 309 N.C. 26, 45, 305 S.E.2d 703, 717 (1983). We do not, however, "necessarily feel bound ... to give a citation to every case in the pool of 'similar cases' used for comparison." Williams, 308 N.C. at 81, 301 S.E.2d at 356. Rather, we limit our consideration to those cases "which are roughly similar with regard to the crime and the defendant...." State v. Lawson, 310 N.C. 632, 648, 314 S.E.2d 493, 503 (1984), cert. denied, 471 U.S. 1120, 105 S.Ct. 2368, 86 L.Ed.2d 267 (1985). If, after making such a comparison, we find that juries have consistently been returning death sentences in the similar cases, then we will have a strong basis for concluding that a death sentence in the case under review is not excessive or disproportionate. On the other hand if we find that juries have consistently been returning life sentences in the similar cases, we will have a strong basis for concluding that a death sentence in the case under review is excessive or disproportionate. Id.

Characteristics distinguishing the present case include (1) a murder of a wife preceded by many years of physical abuse and threats to her; (2) fear on the part of the victim; (3) a calculated plan of attack by the defendant; (4) a senseless and brutal stabbing in front of other people, found to be "especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel" by the jury; (5) a period of time in which the victim suffered great physical and psychological pain before death; and (6) a distinct failure by the defendant to exhibit remorse after the killing. The jury found only one statutory mitigating circumstance, that the crime was committed while the defendant was under the influence of mental or emotional disturbance. It found five non-statutory mitigating circumstances: that defendant understands the severity of his conduct; that he has, since his incarceration, demonstrated an ability to abide by lawful authority; that he has a history of good work habits; that he has a history of being a good family provider; and that he has been a person of good character or reputation in the community in which he lived. It found two circumstances under the catchall: that the defendant was raised in a different culture and that he was aggravated by events following the issuance of the ex parte domestic violence order.

Of the cases in which this Court has found the death penalty disproportionate, only two involved the "especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel" aggravating circumstance. State v. Stokes, 319 N.C. 1, 352 S.E.2d 653 (1987); State v. Bondurant, 309 N.C. 674, 309 S.E.2d 170 (1983). Neither is similar to this case. In Stokes, the defendant and several others planned to rob the victim's place of business. During the robbery one of the assailants severely beat the victim about the head, killing him. Stokes, 319 N.C. at 3, 352 S.E.2d at 654. We find the dissimilarities between Stokes and this case significant. First, the defendant in Stokes was seventeen-years-old; defendant in this case is fifty-two-years-old. Second, the defendant in Stokes was convicted on a felony murder theory. There was virtually no evidence of premeditation and deliberation. In the present case, defendant was convicted on a theory of premeditation and deliberation, and there was substantial evidence of both premeditation and deliberation. There was also no evidence in Stokes showing who was the ringleader in the robbery, or that the defendant deserved a death sentence any more than did an older confederate who received a life sentence.

In Bondurant, the defendant shot the victim while they were riding together in a car. Bondurant, 309 N.C. at 677, 309 S.E.2d at 173. The Court "deem [ed] it important in amelioration of defendant's senseless act that immediately after he shot the victim, he exhibited a concern for [the victim's] life and remorse for his action by directing the driver of the automobile to the hospital." Id. at 694, 309 S.E.2d at 182. He then went inside to secure medical treatment for the victim. The defendant also spoke with the police at the hospital, confessing that he shot the victim. In the present case, by contrast, the defendant offered neither comfort nor help to his wife, nor did he attempt to secure help from others. As his son returned to his mother, after running off to seek help, defendant yelled at him in Arabic, "Bastard." Then defendant left the scene and drove to a nearby fire station, where he told a fireman that he needed medical attention because he had been in a fight. His later expressions of remorse at the trial are not comparable to the actions taken by the defendant in Bondurant.

There are three similar cases in the pool in which the jury recommended a sentence of death after finding as an aggravating circumstance that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel. State v. Spruill, 320 N.C. 688, 360 S.E.2d 667 (1987), cert. denied, 486 U.S. 1061, 108 S.Ct. 2833, 100 L.Ed.2d 934 (1988); Huffstetler, 312 N.C. 92, 322 S.E.2d 110; State v. Martin, 303 N.C. 246, 278 S.E.2d 214, cert. denied, 454 U.S. 933, 102 S.Ct. 431, 70 L.Ed.2d 240, reh'g denied, 454 U.S. 1117, 102 S.Ct. 693, 70 L.Ed.2d 655 (1981). Further, we believe that another case--State v. Boyd, 311 N.C. 408, 319 S.E.2d 189 (1984), cert. denied, 471 U.S. 1030, 105 S.Ct. 2052, 85 L.Ed.2d 324 (1985)--is similar, and comparison to the present case is warranted.

In Huffstetler, defendant beat his mother-in-law to death with a cast iron skillet after an argument. The victim had multiple wounds on her head, neck and shoulders. Her jaw, neck, spine and collarbone were fractured. After beating the victim, the defendant went home to change his bloody clothes, returned to the scene to remove the skillet, and went to visit a woman friend. Huffstetler, 312 N.C. at 98-100, 322 S.E.2d at 115-16. The jury in Huffstetler found as the single aggravating circumstance that the murder was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel. Id. at 100, 322 S.E.2d at 116. The jury also found three mitigating circumstances: that the defendant's capacity to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law was impaired; that the killing occurred contemporaneously with an argument and by means of an instrument acquired at the scene and not taken there; and that the defendant did not have a history of violent conduct. Id. Notwithstanding the fact that defendant suffered from an emotional or mental disorder, this Court concluded that the sentence of death was not disproportionate, based on evidence similar to that in the present case, including the brutal nature of the killing, the lack of remorse shown by the defendant, and the defendant's cool actions after the murder.