1st murderer executed in U.S. in 1979

2nd murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Florida in 1979

1st murderer executed in Florida since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

| |

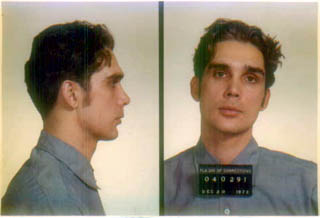

John Arthur Spenkelink

W / M / 23 - 30 |

Joseph J. Szymankiewicz W / M / 45 |

Summary:

On February 4, 1973, the 24 year old Spenkelink, a twice convicted felon and an escapee from a California correctional camp, picked up Joseph J. Szymankiewicz, a hitchhiker, while traveling in the midwest. Both men had criminal records, and both were heavy drinkers. They checked into a hotel room in Tallahassee. After Spenkelink left to wash the car, he returned and shot Szymankiewicz while he slept in bed, once in the head just behind the left ear and a second time in the back. He then told a cover story to the hotel proprietor, paid for an extra day, and left with Frank Bruum, another hitchiker. Spenkelink claimed that he shot Szymankiewicz in self-defense in that he forced sexual relations on him earlier, and forced him to play "russian roulette." He also claimed that the gun went off accidentally during a fight between the two. Less than one week later, Spenkelink and Bruum were arrested for suspicion of armed robbery in Buena Park, California. The murder weapon was found in an apartment leased to Bruum and others. Upon their return to Florida both were tried for First Degree Murder. Spenkelink was found guilty and Bruum was acquitted.

Spenkelink was the first murderer executed in Florida, and the second nationwide, following the reinstatement of capital punishment in 1976. Unlike the first, Gary Gilmore, Spenkelink contested his execution to the end.

Citations:

Spinkellink v. State, 313 So.2d 666 (Fla.1975) (Direct Appeal).

Spinkellink v. Florida, 428 U.S. 911, 96 S.Ct. 3227 (1976) (Cert. Denied).

Spenkelink v. State, 350 So.2d 85 (1977) (State Habeas).

Spinkellink v. Florida, 434 U.S. 960 (1977) (Cert. Denied).

Spinkellink v. Wainwright, 578 F.2d 582 (5th Cir. 1978) (Habeas).

Spinkellink v. Wainwright, 442 U.S. 1301 (1979) (Stay).

Final / Special Meal:

(Prior to execution, an inmate may request a last meal. To avoid extravagance, the food to prepare the last meal must cost no more than $40 and must be purchased locally)

Last / Final Words:

"Capital punishment -- Them without the capital get the punishment."

Internet Sources:

Florida Department of Corrections

Inmate:Spenkelink, JohnRace / Gender: White Male

DOB: 03/29/49

Date of Offense: 02/03/73

Date Sentenced: 12/20/73

Date Received: 12/20/73

Date of Execution: 05/25/79

Years on Death Row: 5.43

County of Conviction: Leon

John Spenkelink

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

John Arthur Spenkelink (March 29, 1949 in Le Mars, Iowa, – May 25, 1979 in Starke, Florida) was the first person executed in Florida (and the second one nationwide) since the re-introduction of the death penalty in the United States in 1976. Unlike the first execution (that of Gary Gilmore in Utah), Spenkelink legally fought his execution until the very end. The last man executed in Florida had been in 1964, and the last execution nationwide had been in Colorado in 1967.

After serving in a California prison for petty crimes, he travelled to Florida with another prison inmate. He was condemned to death in 1973 for murdering a traveling companion (named Joseph J. Szymankiewicz) who, Spenkelink alleged, had offered him homosexual relations and then forced him to play Russian roulette in a Tallahassee, Florida, motel.

Spenkelink's case raised some controversy since he claimed that he shot his victim in self-defense. According to Spenkelink's attorney, there was a good chance the sentence would be commuted. Spenkelink had been offered a chance to admit to second-degree murder and to receive a life-in-prison sentence, but he refused to do so.

In 1977, Governor Reubin Askew of Florida signed his first death warrant, but the Supreme Court stayed the execution. In 1979, the new governor of Florida, Bob Graham, signed a second death warrant and, despite the temporary ruling of Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, this was the final death warrant, since the full U.S. Supreme Court overturned Marshall's stay of execution.

Among those who were protesting against his execution outside gubernatorial mansion were for example former Florida Governor LeRoy Collins, actor Alan Alda and singer Joan Baez.

After the execution, unfounded rumors spread that the fighting, shouting Spenkelink was dragged to the electric chair, gagged, beaten, and had his neck broken. The rumors caused Spenkelink's body to be exhumed for an autopsy, and the State of Florida further ruled that autopsies be performed on all executed inmates. Some witnesses believe that Spenkelink was already dead when placed in the electric chair. In David Von Brehle's book on the Florida death row system, Among the Lowest of the Dead, the author presented several interviews with eyewitnesses who saw Spenkelink alive in the electric chair before his death. According to these witnesses, Spenkelink did not resist being put into the electric chair by the officers in charge.

In 1989, Ted Bundy occupied the same cell at Florida State Prison that Spenkelink had occupied.

"Execution to mark death penalty anniversary; Florida reinstated the death penalty 25 years ago." (AP May 23. 2004 6:01AM)

STARKE - Twenty-five years after convicted killer John Spenkelink died in the electric chair, Florida will mark the anniversary by preparing for the death of an inmate who claims he killed in prison so he could be executed.

It was an unsure time in the late 1970s when Florida prepared to carry out the first involuntary execution of a convicted felon since a U.S. Supreme Court ban on capital punishment was overturned. Florida did not have an executioner. It had not used the electric chair in 15 years. It had no written procedures on how to conduct an execution.

Despite those problems, on May 25, 1979, Spenkelink was put to death for the 1973 slaying of Joseph Szymankiewicz in a Tallahassee motel room. Szymankiewicz had been shot twice and beaten in the head after Spenkelink said the man forced him at gunpoint to commit a homosexual act.

Since executions resumed, 910 people have been executed in the United States, including 58 in Florida, according to the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington, D.C.

In Florida, serial killers Ted Bundy and Gerald Stano, "black widow" killer Judy Buenoano and Death Row sage Willie Darden were among the 44 inmates strapped in the same three-legged oaken electric chair known as "Old Sparky." Another 14, including Aileen Wuornos, one of the few female serial killers, have died by injection. In that same quarter century, Florida also leads the nation in the number of inmates freed from Death Row with 25.

On the 25th anniversary of Spenkelink's death, the state is preparing to execute John Blackwelder, a 49-year-old convicted child molester who originally was sentenced to life in prison. That the execution is set to fall on the death penalty anniversary is a coincidence, state prison officials say.

David Kendall, a Washington, D.C., lawyer who represented Spenkelink, thought his client had a good chance to avoid execution. "We believed this was an excellent case for a commutation of sentence," Kendall said in a telephone interview. "Everyone expected something to happen so John Spenkelink would not be executed."

Prior to trial, Spenkelink rejected an offer to plead guilty to second-degree murder and avoid the death penalty. "He felt it was not murder, but self-defense," Kendall recalled.

At Spenkelink's clemency hearing a month before his execution, chief prosecutor Anthony Guarisco disputed the self-defense theory, and was quoted in David Von Drehle's book, "Among the Lowest of the Dead," saying, "So what we have is an individual sneaking up on the victim, who is asleep, and shooting him. Shooting him in the back of the head! Shooting him in the back! Bashing in his head with some unknown instrument! So this is really not a case of self-defense!"

Michael Mello, a professor at the Vermont Law School, who worked on the cases of Bundy and Unabomber Theodore Kaczynski, said Spenkelink's case helped establish the procedures used for post-conviction appeals in capital cases. "For better or worse, it became the template of what came afterwards," Mello said.

After the Supreme Court blocked executions nationwide in 1972, Florida was the first to draft a new state law. It was declared constitutional in 1976. The following year, Gov. Reubin Askew signed Spenkelink's first death warrant, but courts stayed the execution. Nearly two years later, Gov. Bob Graham - who is now a U.S. senator - signed the warrant that would end Spenkelink's life. Demonstrators protested outside the governor's mansion beating a drum and then filled the lobby of Graham's office the next day.

"What a nightmare that was," said Jim Smith, who was Florida attorney general at the time. "We were doing what we had to do to make sure that the execution occurred. . . . This was the law of the state and it was my job to see that it was carried out."

Both David Brierton, who was Florida State Prison superintendent at the time, and Richard Dugger, the assistant superintendent who went on to become state corrections secretary, declined to be interviewed for this report. Brierton was criticized for his plans to keep the blinds drawn in the execution chamber until Spenkelink was strapped in. Brierton hoped to prevent a circus-like atmosphere at the prison like that when Gary Gilmore asked to be executed before Utah's firing squad in 1977. Instead, the closed blinds led to accusations that Spenkelink had been mistreated and prevented from making a last statement. An investigation found no evidence he had been mistreated.

Brierton said earlier he had two fears - the chair wouldn't work or the governor would call five minutes after it was over and say there was a stay. But there would be no stay. After being served two shots of Jack Daniels by Dugger, Spenkelink was put to death.

Andy Johnson, then a state representative from Jacksonville, witnessed the execution. "Not a pretty sight. I had nightmares for years," he said in an e-mail response to questions from The Associated Press. Johnson, who now hosts a radio talk show in Jacksonville, said he believed the execution "was a sad mistake. Spenkelink had killed in self-defense." "I do support the death penalty as a matter of justice, and, frankly, revenge, if only we could do a better job of being fair, precise and accurate, and if the death penalty could be applied without regard for one's economic status," Johnson said.

In the 25 years since Spenkelink's death, Florida has seen the electric chair malfunction twice, with flames leaping from the heads of Pedro Medina and Jesse Tafero. The execution of Allen "Tiny" Davis on July 8, 1999, marked the end of the chair after pictures of his bloody face appeared on the Internet. The Florida Legislature changed the method of execution to injection in 2000.

While awaiting execution, Spenkelink composed his own epitaph. "Man is what he chooses to become. He chooses that for himself."

Monday, Jun. 04, 1979

Nation: At Issue: Crime and Punishment - Florida ends the nation's moratorium on executions

The Venetian blinds in the tiny brown chamber at the Florida State Prison opened at 10:11 a.m., giving the 32 witnesses their first glimpse through the glass partition at the condemned man. He was strapped tightly into the stout oak chair, a black gag across his mouth. Suddenly a black hood dropped over his face, and six attendants stepped back. The executioner, his identity a secret and his face also shrouded in black, flipped a red switch, sending 2,250 volts of electricity through the man's body, then two more surges. At 10:18 a.m., a doctor pronounced him dead, and the Venetian blinds closed.

So ended last week the life of John Spenkelink, 30, a wiry drifter and habitual criminal, after a frenzied week of final appeals, to the Florida Supreme Court, to the Federal Appeals Court and to the U.S. Supreme Court. He had won two brief stays, then lost them both because of pleas by Florida officials who were determined to put him to death.

Finally, he had kissed his mother and girlfriend goodbye, taken Communion and delivered to Episcopal Priest Thomas Feamster a cryptic epitaph: "Man is what he chooses to be. He chooses that for himself."

Spenkelink was the first person involuntarily executed in the U.S. since 1967,* and the reactions were immediate. Outside Spenkelink's cell, the 130 other condemned men on Florida's death row shouted and pounded on cell bars. Some 70 demonstrators gathered in the warm spring sun on a field near the prison, chanting "Death row must go" and singing "We shall overcome."

Spenkelink's death intensified the national debate that has long raged over whether capital punishment deters crime and should be retained or is a cruel and unfair form of revenge that ought to be abolished. Sociologists have never definitively answered the question, but the views of the American public, aroused by violent crime, seem clear: polls show that nearly two-thirds of the people favor capital punishment. Accordingly, after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1972 against the arbitrary way in which capital punishment was imposed, 34 states have rewritten their death penalty laws to conform with the court's guidelines. State courts have imposed death sentences on about 500 people, nearly half of them black men and all but one of them convicted of murder. Opponents of capital punishment fear that Spenkelink's death, ending an unofficial moratorium, may lead to a wave of executions. Most of them will be in the Deep South, which has traditionally led the nation in imposing that penalty.

It was thus with a sense of urgency that many of the leading opponents of capital punishment assembled in Florida last week to stage a last-minute campaign for the hapless Spenkelink. Henry Schwarzschild of the American Civil Liberties Union warned of a "constitutional, legal and political disaster that will shock and appall the rest of the world." Former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark, a late addition to Spenkelink's defense team, called the occasion "a tragic moment in American history" and gibed, "If you work at city hall you get voluntary manslaughter," a caustic reference to the lenient verdict against Dan White, the slayer of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk (see box).

The final act of the Florida drama began in Tallahassee at 6:46 a.m. on Friday, May 18, when Governor Robert Graham signed two black-bordered death warrants. One was for Willie Jasper Darden, 45, a professional robber who had been convicted of murdering a furniture store owner in Lakeland, Fla., in 1973. Darden's lawyers soon won an indefinite stay of execution so that a federal judge could consider their argument that the prosecutor prejudiced the jury at Darden's trial by saying that the defendant "shouldn't be out of his cell unless he has a leash on him."

The second warrant was for John Arthur Spenkelink, a moody loner who had been in and out of jail since childhood. Spenkelink's troubles began early; at twelve he discovered the body of his alcoholic father, who had committed suicide in the front seat of his truck in Buena Park, Calif. Two years later, Spenkelink was arrested for the first time, for driving a stolen car. There followed arrests for disturbing the peace, for burglary and for armed robbery. Stints in reform schools were to no avail. When he married briefly at 18, his probation officer could find only two positive things to say about him: he had not been in trouble before his teens and he had been "a wonderful paper boy."

In 1972, while Spenkelink was serving a five-year sentence for armed robbery, he walked away from the minimum-security Slack Canyon Conservation Camp near Big Sur. Driving through Nebraska, he picked up a hitchhiker, Joe Szymankiewicz, 43, an Ohio parole violator who had spent 16 years behind bars for forgery, burglary, theft and other crimes. For several weeks they roamed the country, ending up on Feb. 3, 1973, in Room 4 of the Ponce de Leon Motel in Tallahassee. Next morning, a maid discovered Szymankiewicz dead in bed. He had been bludgeoned and shot twice.

At his trial that fall, the slightly built Spenkelink admitted having killed his companion but insisted that he had acted in self-defense: the muscular, 230-lb. Szymankiewicz, said the defendant, had stolen $8,000 from him, forced him at gunpoint to perform fellatio and made him play Russian roulette. But the wounds were all from behind, and the jury took only 3½ hours to convict Spenkelink of murder and sentence him to death. His lawyers filed 22 appeals, claiming that the death penalty is cruel and unusual punishment, that it is unfairly applied more often to murderers of whites than of blacks and that the jury was improperly selected. Judges called some of the arguments "frivolous" and "shams" and rejected them all. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court four times and was four times rejected.

Living in prison for six years under constant threat of death wonderfully concentrated Spenkelink's mind. He spent hours reading the Bible and such works as the mystic prophecies of Edgar Cayce. He drew cartoons with religious messages and once sent his mother a picture of a red, white and blue electric chair captioned, "Spirit of '76." He wrote letters for illiterate inmates and designed stationery for others, decorating the letterheads with hands clasped in prayer. "If I ever get out of here," he said at one point, "I'll do God's work." He occupied much of each day answering his mail, inscribing envelopes with the message: CAPITAL PUNISHMENT MEANS THOSE WITHOUT CAPITAL GET THE PUNISHMENT. Twice a week he was visited by a girlfriend, divorcee Carla Key, 43.

His defenders insisted that Spenkelink had been rehabilitated. "If you want to execute a bad kid, then this is the case," his chief attorney, David Kendall, told the clemency board in April. "But he has evolved, he has changed." The clemency appeal was turned down.

Spenkelink begged the Governor to meet with him. Said the condemned man: "I know the changes I've made since being here. I want him to know who he is killing—the real person, not some idea he has in his head about me." Said Spenkelink's anguished mother Lois, 67, of the Governor: "He doesn't even know my son. How can he kill my son, my only son?"

But Graham, looking haggard, stayed in Tallahassee, avoiding anti-death penalty protesters who blocked his outer office at the state capitol and who kept vigil at the front gate of his mansion, chanting "Bloody Bob! Bloody Bob!" Graham supports capital punishment as a deterrent, maintaining that it is "not inconsistent with Christian values." Said he, while signing the death warrants: "There are other values of life involved here, including the value of the lives that were taken."

With only a few hours left, Spenkelink's lawyers made their final appeals. Three lawyers, including Clark, argued before Federal Judge Elbert Tuttle that the court-appointed lawyers who defended Spenkelink at his trial were ineffective. In Washington, Lawyer Joel Berger went from Justice to Justice. Finally, Thurgood Marshall ordered that the execution be stayed. Almost simultaneously, Judge Tuttle did too.

Next morning, the full Supreme Court briefly considered Spenkelink's appeal and voted 7 to 2 to turn it down. In New Orleans, a panel of three federal judges deliberated into the night, then rejected it too. Spenkelink's lawyers appealed once more to the Supreme Court in Washington. At 9:50 a.m. on Friday, only ten minutes before the scheduled execution, the court refused again, by 6 to 2. Almost immediately, Spenkelink, his arms heavily manacled, was led into the death chamber next door.

*The last to die that year was Luis Jose Monge, who was gassed in Colorado for murdering his pregnant wife and three children. In 1977, Murderer Gary Gilmore was executed in Utah, but he scorned all appeals and went willingly before the firing squad, saying just before his death, "Let's do it."

ABOLISH Archives - Rick Halperin

5-23-99 (FLORIDA):

In Starke, drum beat outside the governor's mansion as the time neared for Florida to execute John Spenkelink. Prison officials prepared for their 1st execution in 15 years. Defense attorneys rushed from court to try to get a last-minute stay.

It was an unsure time 20 years ago as Florida prepared to carry out the 1st involuntary execution of a convicted felon since a U.S. Supreme Court ban on capital punishment was overturned. Since then, 544 people have been executed in the United States, including 43 in Florida. Serial killers Te d Bundy and Gerald Stano, "black widow" killer Judy Buenoano and death row sage Willie Darden have been among those strapped to the same 3-legged oaken electric chair known as "Old Sparky."

Spenkelink, however, always will be remembered as the 1st. "It was one of the most searing experiences of my governorship," said former Gov. Bob Graham, now a U.S. senator.

On May 25, 1979, Spenkelink, 30, was put to death for the 1973 slaying of Joseph Szymankiewicz in a Tallahassee motel room. Szymankiewicz, 45, had been shot twice and beaten in the head with a hatchet after Spenkelink said the man forced him at gunpoint to commit a homosexual act. Spenkelink escaped from a California prison in 1972, where he was serving a 5-years-to-life sentence for robbing a fast-food restaurant, 5 gas stations and 2 people. In the Florida case, Spenkelink rejected a plea bargain to spare his life. He was convicted and sentenced to death.

After the Supreme Court blocked executions nationwide in 1972, Florida was the 1st to draft a new state law. It was declared constitutional in 1976. The following year, Gov. Reubin Askew signed Spenkelink's 1st black-bordered death warrant, but hi s execution was stayed by courts. Twenty months later, Graham would sign the warrant that ended Spenkelink's life. Demonstrators protested outside the governor's mansion, then filled the lobby of Graham's office the next day.

Graham recalled the protests as "very frightening to my young daughters. I had to spend a lot of time reassuring them why this was happening, that this was part of what it was to be in a country that respected freedom of speech." There also were logistical hurdles. When the state decided to resume executions, officials realized no one knew how to operate the chair. There was no written procedure on how to carry out an execution. There was no executioner. "We had to start from scratch and rely on people's memories," said Richard Dugger, then assistant superintendent of Florida State Prison. He eventually rose to head the state Department of Corrections.

Superintendent Dave Brierton, who oversaw the Spenkelink execution, came under criticism for his plans to keep the blinds drawn in the execution chamber until Spenkelink was strapped in. Brierton hoped to prevent a circus-like atmosphere at the prison like that when Gary Gilmore asked to be executed before Utah's firing squad in 1977. Instead, the closed blinds led to accusations that Spenkelink had been mistreated and prevented from making a last statement. An investigation found no evidence that he had been mistreated.

Just prior to the execution , Brierton pulled a bottle of Jack Daniels out of his desk and asked Dugger to offer Spenkelink a drink. "It was to take the edge off," said Brierton, noting that throughout history the condemned had been offered a drink - even Anne Boleyn, 2nd wife of Henry VIII. Spenkelink took 2 swigs from the bottle.

"It was a very difficult time for Spenkelink. It was a very difficult time for me," said Brierton. "It was the loss of a human life." Brierton said he had 2 fears - the chair wouldn't work or the governor would call 5 minutes after it was over and say there was a stay. But there would be no stay. "I was determined and Gov. Graham was determined that the laws of Florida be carried out," said Jim Smith, Florida's attorney general at the time. "It was a very emotional day. There was no great joy."

Andy Johnson, then a state representative opposed to the death penalty, witnessed the execution. "We saw a man sizzle today , and if you leaned forward and looked close you could see that he sizzled and sizzled again," he said that day. Johnson, who now hosts a radio talk show in Jacksonville, has since changed his stance on the death penalty. "It's a matter of justice and vengeance. There are some people who deserve to die," he said.

Contrary to the predictions of opponents, Smith noted, Spenkelink's death did not start a flood of executions that would empty death row. There are 375 people on Florida's death row today compared with 134 in 1979. While awaiting execution, Spenkelink composed his own epitaph. "Man is what he chooses to become. He chooses that for himself."

(Source: Associated Press)

ABOLISH Archives - Rick Halperin

April 2001 - Execution witnesses become part of this barbaric apparatus

Timothy McVeigh will be executed by lethal injection on May 16 before a much smaller audience than he wanted. Not millions of voyeurs, just those whose job it is to carry out the death penalty, media witnesses, survivors of the bombing and family members of some of the victims. And what do the latter want from the experience? Revenge, for some, and the perhaps over-worked concept of "closure" for others.

I can't imagine actually wanting to see an execution carried out. That's because I already have done it, and I would never do it again. Reasonable people can disagree over the death penalty and over whether executions should be televised. Perhaps family members, with their lives destroyed and emotions yet unhealed, can be excused for wanting to see with their own eyes McVeigh's last breath. But I wonder how many will be glad they did.

The man whose execution I witnessed was named John Spenkelink. He was the first person in the United States to die in the electric chair after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, following a four-year moratorium, that the states could resume the business of killing criminals. Gary Gilmore had the dubious honor of actually being the first to be executed after the court's green light, but Gilmore had asked to be put out of his misery. A Utah firing squad gave him his wish in 1977.

Spenkelink, who got into a bar fight in Florida with a drifter named Joseph Szymankiewicz and killed him, fought his execution until the end, which came on the early morning of May 25, 1979.

As an Atlanta-based correspondent for ABC News, I had been put on notice that when Spenkelink's appeals ended, and his time to die came, the story would be mine. Not only that, but I would get to watch. I was not thrilled. I was then and am today adamantly opposed to the death penalty. I was willing to cover the story as a professional newsman, but I did not want to watch the execution. The witnesses would, in effect, be part of the apparatus set up to take a life.

But my superiors insisted. The alternative, I was assured, was to be replaced on the story. "There are plenty of people ready to come down and watch the guy die," a New York news executive warned me, "so decide which it will be." I reluctantly agreed to be a witness, a decision that I have regretted ever since.

On the morning of the execution, I got up, shaved, dressed and prepared to watch the premeditated taking of a human life. Reporters and other witnesses were told to gather at 6 a.m. in a field across from the rural prison. We were taken by white prison buses to the death chamber. There was little talk. We were led into a concrete-walled room with folding chairs facing a rectangular glass wall.

Suddenly, curtains were pulled over the glass partition, and we strained to see what was happening beyond them. Then, just as suddenly, the curtains parted. And there, seated before us, was Spenkelink. Metal contacts covered the top of his head, a mask hid his face, his legs and arms were strapped tightly to "Old Sparky." Through the eyeholes in the face mask, we could see his gleaming eyes, darting side-to-side, as if in terror.

At 7 a.m., the appointed time, fellow inmates grabbed cell bars and shook them violently for several minutes, sending waves of metallic rattling sounds throughout the old prison. It was their noisy send-off for Spenkelink.

The first jolt of electricity caused him to stiffen, his back straightening into the rigid chair back, and his fingers extending, then clutching as if trying unsuccessfully to make a fist. The second jolt caused his body to jerk, then relax. A doctor examined Spenkelink with a stethoscope, silently declared him dead, and the curtains closed again. The whole thing had taken only a few minutes.

I felt diminished by the experience, ashamed that I had taken part in a barbaric process. Killing killers validates the latters' value system and undermines our claim on civility. The French writer/philosopher Albert Camus said it best: "For there to be an equivalency, the death penalty would have to punish a criminal who had warned his victim of the date at which he would inflict a horrible death on him and who, from that moment onward, had confined him at his mercy for months. Such a monster is not encountered in private life."

I had been an unwilling part of the machinery of premeditated murder, committed in the imperfect name of the state. I didn't think I would ever get over it. I was right. Those who want to watch Timothy McVeigh die should consider how debased he was to commit premeditated murder, and ask, "Who wants to be like him?"

(Source: Opinion, Al Dale, of Atlanta, is a former ABC News correspondent; Atlanta Journal-Constitution)

"The Story of Old Sparky," by Sydney Freedberg. (September 25, 1999 )

In 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the death penalty, ruling that it had been applied unfairly. Florida and other states rushed to rewrite less-arbitrary laws. When the court upheld them four years later, Oklahoma became the first state to switch to lethal injection. Texas, worried about the possibility of a televised death in the electric chair, followed suit and became the first state to use the method in 1982. But Florida was determined to keep Old Sparky and its time-honored death rituals.

The first to die when executions resumed in Florida was John Spenkelink, a white man condemned for murdering his roommate in a Tallahassee motel. In vain, Spenkelink's lawyers -- among them David Kendall, who later became President Clinton's private attorney -- argued that the electric chair was "unnecessarily torturous and wantonly cruel."

On May 25, 1979, Spenkelink, 30, was given two shots of whiskey, then executed in front of 32 witnesses, including 10 reporters. It took three jolts to kill him. But because the venetian blinds separating the witness section from the death chamber were closed until Spenkelink was strapped in, witnesses did not get a good look. Spenkelink had straps drawn tightly across his mouth and was denied a final statement by prison officials.

After the execution, rumors spread that a fighting, shouting Spenkelink had been dragged to the chair, gagged and beaten, so officials decided to leave the blinds open the next time. And after Spenkelink's body was exhumed for an autopsy, the state decided to perform autopsies on all executed inmates, a job that fell to William Hamilton, the Gainesville-area medical examiner.

Spinkellink v. State, 313 So.2d 666 (Fla.1975) (Direct Appeal)

The Leon County Circuit Court, John A. Rudd, Sr., J., found defendant guilty of murder in the first degree, sentenced him to death, and he appealed. The Supreme Court, Boyd, J., held that (1) under the 'plain view' doctrine, gun was properly seized by the police during warrantless search of defendant's California apartment which he shared with two others, where, despite defendant's claim that the gun was found in his bedroom in a drawer, the record clearly showed that it was found in open drawer in kitchen; furthermore, since a codefendant, who had been arrested on suspicion of armed robbery, was only a few feet away from the drawer containing the gun, it fell within the 'search incident to arrest' exception, whereby an arresting officer may search the area into which an arrestee might reach in order to grab a weapon or evidentiary item, (2) premeditation was established by the evidence, including proof that defendant endeavored to evade prosecution by flight and that, shortly before the homicide, he warned a companion that, should the latter happen to hear a gunshot, it would come from defendant's motel room, and (3) the aggravating circumstances disclosed by the record justified imposition of the death sentence. Conviction and sentence affirmed. Ervin (Retired), J., dissented with opinion.

The pertinent facts appears as follows. The 24 year old Appellant picked up Joseph J. Szymankiewicz, a hitchhiker, while traveling in the mid-west; both men had criminal records, and both were heavy drinkers. During their travels Appellant learned first hand of Szymankiewicz's vicious propensities when the latter forced him to have homosexual relations with him, when the latter played 'Russian Roulette' with him and boasted of killing a fellow inmate while in prison. After checking into a motel in Tallahassee, Appellant discovered that his traveling companion had relieved him of his cash reserves. Appellant concluded that it would be wise to continue his journey without Szymankiewicz, and, having had his car washed, Appellant admits that he returned to the motel to remove his personal belongings and to force Szymankiewicz to return the money stolen from him. On his return to the motel, he picked up one Frank Bruum, another hitchhiker, and agreed to take him as far as New Orleans.

Appellant's testimony is of interest at this juncture: 'We started back toward the motel and I told this guy, I said, 'If you don't mind waiting a little ways from the motel, I think it would be better, because there is another guy in the motel room that is pretty drunk. He's going to be mad because I was gone this long.' And I didn't mention nothing to the hitchhiker about Joe taking my money or hiding my money. And--well, I dropped him off a little ways from the motel And I told him if he should happen to hear a gunshot or something, It's in the Ponce de Leon Motel in No. 4. And so what I intended on doing was carrying the (Joe's) gun on me and going into the motel room, and if I had to, by pointing the gun I was going to pick up my baggage and leave that motel room.' (Emphasis supplied.)

He also testified that he hid the pistol in his clothing; and while admitting that he had fired the gun that killed Szymankiewicz, Appellant sought to show mitigating circumstances by showing, first, that he was carrying the gun because he was afraid for his own life, and, secondly, that the gun discharged during a fight between the two. The evidence shows that, although Szymankiewicz was shot once in the head, he died from a second bullet fragmenting the spine and rupturing the aorta. It is undisputed that Appellant prepared a cover story to delay discovery of the body, giving him the opportunity to leave with Bruum.

Less than one week later Appellant, along with two others, was in custody for suspicion of armed robbery in Buena Park, California. One of the other suspects was John Moore, a hitchhiker who had been picked up in Texas by Appellant (alias Derek or Derk) and another known to Moore only as Frank. The California police learned that all three had signed the apartment lease, Moore signing as 'uncle' to 'Derek' and Frank; the authorities, having secured Moore's verbal permission to search the apartment and having the use of his key, discovered an intoxicated Frank Bruum at the apartment and placed him under arrest for suspicion of armed robbery. A search ensued, and in an open kitchen drawer was found the gun that later proved to be the murder weapon in Szymankiewicz' death.

After their California arrest, Bruum and Appellant were returned to Florida and tried for first degree murder. The jury returned a verdict of guilty as to Appellant and not guilty as to Bruum. After a subsequent mitigation trial, the jury brought in its advisory verdict recommending that the court impose a sentence of death on Appellant. The trial judge, having considered this advisory verdict, sentenced Appellant to death, filing the appropriate findings of facts. This appeal followed.

It is Appellant's position that, while he shot the deceased, it was in self defense. Admittedly, the evidence clearly shows that the deceased was an individual of vicious temperament and that Appellant was justified in concluding that he would do well to sever their relationship, continuing his odyssey without his companion. Nevertheless, the evidence also is clear that Appellant was alone in his car away from the motel with the opportunity for leaving Szymankiewicz and did not do so; instead, he voluntarily returned to the motel with the deceased's gun hidden, telling Bruum 'if he should happen to hear a gunshot or something, it's in the Ponce de Leon Motel in No. 4'. Additionally, although Appellant claims the gun was fired during a violent, life-or-death struggle with deceased in which he was fighting for his life, the firearms examiner testified that the laboratory test-firing reproduced the pattern of powder residue found on the outer surface of the pillow case so as to indicate that the weapon was fired alongside the pillow rather than through it. Furthermore, Appellant did not contradict the evidence that he established a cover-up which enabled him to flee the scene of the crime with Bruum, saying merely that he remembers nothing after the first shot was fired. The rule is that, when a suspect endeavors to evade prosecution by flight, such fact may be shown in evidence as one of the circumstances from which guilt may be inferred.

Keeping these facts in mind, we note that, when Appellant moved for an acquittal, he admitted the facts adduced in evidence and every conclusion favorable to the Appellee which is fairly and reasonably inferable therefrom.Additionally, it has been held that premeditation may be established by circumstantial evidence. 'Premeditation, like other factual circumstances, may be established by circumstantial evidence. Evidence from which premeditation may be inferred includes such matters as the nature of the weapon used, the presence or absence of adequate provocation, previous difficulties between the parties, the manner in which the homicide was committed, and the nature and manner of the wounds inflicted. It must exist for such time before the homicide as will enable the accused to be conscious of the nature of the deed he is about to commit and the probable result to flow from it in so far as the life of his victim is concerned. No definite length of time for it to exist has been set and indeed could not be. . . .'

It seems clear in this case that Appellant expected to use the gun when he warned Bruum that, should the latter happen to hear a gunshot, it would be in his motel room.

Spenkellink v. Wainwright, 578 F.2d 582 (5th Cir. 1978). (Habeas)

State inmate under sentence of death sought writ of habeas corpus. The United States District Court for the Northern District of Florida, William H. Stafford, J., dismissed petition, and inmate appealed. The Court of Appeals, Ainsworth, Circuit Judge, held that: (1) district court did not err in its conduct with respect to habeas evidentiary hearing; (2) exclusion of two veniremen who had conscientious scruples against death penalty did not violate defendant's constitutional rights; (3) application of Florida death penalty statute did not violate defendant's constitutional rights; (4) Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to clemency decision by the Governor and Cabinet of Florida, and (5) since no cause or prejudice was shown, objection as to admission of one of defendant's custodial statements was waived by his failure to object at trial; and (6) death penalty statute was not unconstitutional on ground that jury was precluded from considering mitigating factors before imposing death penalty. Affirmed.

This case involves the petition for a writ of habeas corpus by a Florida state inmate under sentence of death. On February 4, 1973, petitioner John A. Spenkelink, a 24-year-old white male and twice convicted felon, who had escaped from a California correctional camp, murdered his traveling companion, Joseph J. Szymankiewicz, a white male, in their Tallahassee, Florida motel room. Spenkelink shot Szymankiewicz, who was asleep in bed, once in the head just behind the left ear and a second time in the back, which fragmented the spine, ruptured the aorta, and resulted in the victim's death. The petitioner then recounted a cover story to the motel proprietor in order to delay discovery of the body and left.[Spenkelink told the proprietor that Szymankiewicz was his brother, that Szymankiewicz was so drunk that Spenkelink could not get him into their automobile, and that Szymankiewicz therefore would be left behind. Spenkelink then paid for an extra night's lodging.]

Authorities apprehended him less than one week later in Buena Park, California. On December 20, 1973, subsequent to a jury verdict of guilty of first degree murder, Spenkelink was sentenced to the death penalty by a Florida state court trial judge on the jury's recommendation. Now, five years later, following an unsuccessful direct appeal and unsuccessful collateral review in the Florida state courts, and two unsuccessful petitions for certiorari to the United States Supreme Court, Spenkelink seeks federal habeas corpus relief. He asks this Court, in effect, to reverse his conviction and annul the decision that he must die for his premeditated act of murder. After reviewing the record with painstaking care and considering each of the petitioner's contentions, we have determined that Spenkelink's conviction and sentence were proper. Accordingly, we affirm the district court's dismissal of his petition for habeas corpus.

Spenkelink contends that he murdered Szymankiewicz in self-defense following a scuffle between the two after Spenkelink had returned to the motel room to retrieve certain belongings that Szymankiewicz allegedly had stolen. Florida contends that Spenkelink murdered Szymankiewicz while he was asleep in bed. The United States Supreme Court in Proffitt v. Florida, described the circumstances in Spenkelink's case as " 'career criminal' shot sleeping traveling companion." Spenkelink contends also that some time before the shooting Szymankiewicz had antagonized and provoked him by, among other things, using him as the target for a game of "Russian roulette" and forcing him to commit oral sodomy at gunpoint. Unfortunately, the only witness to these alleged activities is Szymankiewicz, who is now dead. The jury apparently disbelieved Spenkelink, as evidenced by its verdict and recommended sentence.

The trial jury recommended that Spenkelink receive the death penalty. The trial court agreed. Pursuant to Fla.Stat.Ann. s 921.141(3), it found that the felony "was committed for pecuniary gain, either for another person's money or to re-coup his own," that the crime "was especially heinous, atrocious and cruel," that Spenkelink "was previously convicted of a felony involving the use, or threat of violence to another, to-wit: armed robbery," and that Spenkelink committed the crime while "under sentence of imprisonment." The only mitigating circumstance found by the trial court was "that possibly the defendant was under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance," a consideration which, "based on the record as a whole," the court did not regard "as a substantial factor." See Fla.Stat.Ann. ss 921.141(5), (6). The Supreme Court of Florida affirmed both the conviction and sentence.

The first degree murder statute under which the petitioner was convicted states:

(a) The unlawful killing of a human being, when perpetrated from a premeditated design to effect the death of the person killed or any human being, or when committed by a person engaged in the perpetration of, or in the attempt to perpetrate, any arson, involuntary sexual battery, robbery, burglary, kidnapping, aircraft piracy, or unlawful throwing, placing, or discharging of a destructive device or bomb, or which resulted from the unlawful distribution of heroin by a person 18 years of age or older when such drug is proven to be the proximate cause of the death of the user, shall be murder in the first degree and shall constitute a capital felony, punishable as provided in s 775.082.

(b) In all cases under this section, the procedure set forth in s 921.141 shall be followed in order to determine sentence of death or life imprisonment. Fla.Stat.Ann. s 782.04(1) (West 1976). The statute has since been amended. Fla.Stat.Ann. s 782.04(1)(a) (West Supp. 1978).

Fla.Stat.Ann. s 775.082(1) provides:

A person who has been convicted of a capital felony shall be punished by life imprisonment and shall be required to serve no less than 25 years before becoming eligible for parole unless the proceeding held to determine sentence according to the procedure set forth in s 921.141 results in findings by the court that such person shall be punished by death, and in the latter event such person shall be punished by death.

Fla.Stat.Ann. s 921.141 provides:

(1) Separate proceedings on issue of penalty. Upon conviction or adjudication of guilt of a defendant of a capital felony, the court shall conduct a separate sentencing proceeding to determine whether the defendant should be sentenced to death or life imprisonment as authorized by s. 775.082. The proceeding shall be conducted by the trial judge before the trial jury as soon as practicable. If, through impossibility or inability, the trial jury is unable to reconvene for a hearing on the issue of penalty, having determined the guilt of the accused, the trial judge may summon a special juror or jurors as provided in chapter 913 to determine the issue of the imposition of the penalty. If the trial jury has been waived, or if the defendant pleaded guilty, the sentencing proceeding shall be conducted before a jury impaneled for that purpose, unless waived by the defendant. In the proceeding, evidence may be presented as to any matter that the court deems relevant to sentence, and shall include matters relating to any of the aggravating or mitigating circumstances enumerated in subsections (5) and (6). Any such evidence which the court deems to have probative value may be received, regardless of its admissibility under the exclusionary rules of evidence, provided the defendant is accorded a fair opportunity to rebut any hearsay statements. However, this subsection shall not be construed to authorize the introduction of any evidence secured in violation of the constitutions of the United States or of the State of Florida. The state and the defendant or his counsel shall be permitted to present argument for or against sentence of death.

(2) Advisory sentence by the jury. After hearing all the evidence, the jury shall deliberate and render an advisory sentence to the court, based upon the following matters:

(a) Whether sufficient aggravating circumstances exist as enumerated in subsection (5);

(b) Whether sufficient mitigating circumstances exist as enumerated in subsection (6), which outweigh the aggravating circumstances found to exist; and

(c) Based on these considerations, whether the defendant should be sentenced to life imprisonment or death.

(3) Findings in support of sentence of death. Notwithstanding the recommendation of a majority of the jury, the court, after weighing the aggravating and mitigating circumstances shall enter a sentence of life imprisonment or death, but if the court imposes a sentence of death, it shall set forth in writing its findings upon which the sentence of death is based as to the facts:

(a) That sufficient aggravating circumstances exist as enumerated in subsection (5), and

(b) That there are insufficient mitigating circumstances, as enumerated in subsection (6), to outweigh the aggravating circumstances.

In each case in which the court imposes the death sentence, the determination of the court shall be supported by specific written findings of fact based upon the circumstances in sub sections (5) and (6) and upon the records of the trial and the sentencing proceedings. If the court does not make the findings requiring the death sentence, the court shall impose sentence of life imprisonment in accordance with s. 775.082.

(4) Review of judgment and sentence. The judgment of conviction and sentence of death shall be subject to automatic review by the Supreme Court of Florida within sixty (60) days after certification by the sentencing court of the entire record, unless the time is extended for an additional period not to exceed thirty (30) days by the Supreme Court for good cause shown. Such review by the Supreme Court shall have priority over all other cases and shall be heard in accordance with rules promulgated by the Supreme Court.

(5) Aggravating circumstances. Aggravating circumstances shall be limited to the following:

(a) The capital felony was committed by a person under sentence of imprisonment.

(b) The defendant was previously convicted of another capital felony or of a felony involving the use or threat of violence to the person.

(c) The defendant knowingly created a great risk of death to many persons.

(d) The capital felony was committed while the defendant was engaged, or was an accomplice, in the commission of, or an attempt to commit, or flight after committing or attempting to commit, any robbery, rape, arson, burglary, kidnapping, or aircraft piracy or the unlawful throwing, placing, or discharging of a destructive device or bomb.

(e) The capital felony was committed for the purpose of avoiding or preventing a lawful arrest or effecting an escape from custody.

(f) The capital felony was committed for pecuniary gain.

(g) The capital felony was committed to disrupt or hinder the lawful exercise of any governmental function or the enforcement of laws.

(h) The capital felony was especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel.

(6) Mitigating circumstances. Mitigating circumstances shall be the following:

(a) The defendant has no significant history of prior criminal activity.

(b) The capital felony was committed while the defendant was under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance.

(c) The victim was a participant in the defendant's conduct or consented to the act.

(d) The defendant was an accomplice in the capital felony committed by another person and his participation was relatively minor.

(e) The defendant acted under extreme duress or under the substantial domination of another person.

(f) The capacity of the defendant to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of law was substantially impaired.

(g) The age of the defendant at the time of the crime.

Spenkellink v. State, 350 So.2d 85 (Fla. 1977). (PCR)

Defendant sought postconviction relief. The Circuit Court, Leon County, John A. Rudd, J., denied relief, and defendant appealed. The Supreme Court held that defendant's affirmative exclusion of jury examination from transcription, together with defendant's failure to raise on appeal the issue of alleged systematic exclusion of jurors, resulted in waiver of defendant's right to raise such claim in proceedings on defendant's motion for postconviction relief. Affirmed. Boyd, England and Hatchett, JJ., concurred specially and filed opinions.

PER CURIAM.

The appellant John A. Spenkelink sought postconviction relief in the trial court under Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure 3.850. From a denial of relief by the trial court, he appeals that decision and requests a stay of execution pending a review by this Court.

This Court has afforded the appellant-defendant an opportunity to fully present the issues to this Court, including oral argument. The State has supplemented the record by furnishing this Court with a certified copy of the transcript of the voir dire examination of the jury. We affirm the trial court's denial of relief and accordingly deny the stay of execution.

The principal point raised by appellant-defendant Spenkelink concerns an assertion that certain jurors were improperly excluded from the jury panel from which the jury was selected. The examination of the jurors was recorded by a court reporter. Appellant Spenkelink has never previously requested that the juror examination be transcribed, and in fact his counsel expressly excluded it from being transcribed in his original appeal to this Court. It has now been transcribed and furnished to this Court at the instance of the State.[FN1] We find the affirmative exclusion by the appellant, coupled with the failure to raise the issue of an alleged systematic exclusion of jurors at the time of the original appeal, waives the right to raise that claim at this stage in these proceedings. Richardson v. State, 247 So.2d 296 (Fla.1971); Wainwright v. Sykes, 433 U.S. 72, 97 S.Ct. 2497, 53 L.Ed.2d 594 (Opinion filed June 23, 1977).

FN1. Although not a basis for our decision, we note that a review of the transcript reflects no violation of the Witherspoon requirement. Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 88 S.Ct. 1770, 20 L.Ed.2d 776 (1968).

The confession issue is controlled by Wainwright v. Sykes, supra. The remaining issues were presented to the United States Supreme Court and rejected by it in Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242, 96 S.Ct. 2960, 49 L.Ed.2d 913 (1976). They also were *86 presented to the United States Supreme Court when this case was before that court and certiorari was denied on July 6, 1976. Spenkelink v. Florida, 428 U.S. 911, 96 S.Ct. 3227, 49 L.Ed.2d 1221 (1976).

For the reasons expressed, the decision of the trial court is affirmed and the motion for stay of execution is denied. No petition for rehearing will be entertained. It is so ordered.

OVERTON, C. J., and ADKINS, BOYD, ENGLAND, SUNBERG, HATCHETT and KARL, JJ., concur. BOYD, ENGLAND and HATCHETT, JJ., concur specially with opinions.

BOYD, Justice, concurring specially.

I authored the original opinion in this case imposing the death penalty and join in this denial of a stay of execution only to comply with requirements of law.

My experience on this Court for almost nine years has convinced me that capital punishment will do little or nothing to reduce crime. Only by returning to fundamentals of religion, ethics and morality can we prevent the destruction of society.

ENGLAND, Justice, concurring.

On the premise that “death is different”, appellant's counsel invited the trial court and now invites us to expand established judicial boundaries in order to accommodate appellant's desire for an evidentiary hearing on a variety of matters. At oral argument before this Court, appellant's counsel identified from among the ten grounds asserted in his motion for post-conviction relief the two major matters he would like considered at an evidentiary hearing the composition of appellant's jury, which he contends was selected in violation of the standards prescribed in Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 88 S.Ct. 1770, 20 L.Ed.2d 776 (1968), and the imposition of the death penalty on appellant in light of data which would establish that Florida's death penalty statute was in this case being applied unconstitutionally.

I readily concede appellant's premise that death is different.[FN1] Moreover, I cannot help but share many of counsel's stated and unstated concerns regarding appellant's impending execution. I cannot, however, for these reasons alone, accept appellant's invitation to discard or set aside well-established principles of law.

FN1. See Sullivan v. Askew, 348 So.2d 312, 317 (Fla.1977) (concurring opinion). Unfortunately, time is not available for the careful written analysis of appellant's contentions which the gravity of the subject matter warrants. [FN2] At the risk of expressing my views inartfully, I deem it important to mention briefly the major reasons for my rejection of what appellant has presented.

FN2. Appellant's execution has been scheduled for 8:30 a. m. on September 19. This appeal and request for a stay were lodged in our Court on September 13. Briefs were ordered filed by 5:00 p. m. on September 14, and oral argument was conducted commencing at 5:30 p. m. on September 15. I have very little trouble with appellant's multiple challenges to our death penalty statute, as applied to appellant in this proceeding.[FN3] None of them is supported by factual allegations, and since this matter began as appellant's first request for post-conviction relief under our Rule of Criminal Procedure 3.850, appellant was obliged to base his claims on specific facts rather than general conclusions.[FN4] To overcome this inherent defect in his motion appellant frankly invites us to expand the scope of Rule 3.850 review in death penalty cases. For a number of reasons, such as the inadvisability of fragmenting legal challenges to a conviction or sentence, the prospect of unending challenges in each death penalty case as the law evolves, and the fact that some of these claims have already been considered and rejected by this Court on appellant's original appeal or otherwise, I *87 must decline appellant's invitation. Although death is indeed different, I do not believe either the federal or the state constitution requires a different basis for according post-conviction relief in death penalty cases, and I see more harm than good in providing one.

FN3. Appellant's Motion to Vacate, etc., at 7-20, paragraphs 5(c)-(j). FN4. E. g., State v. Weeks, 166 So.2d 892 (Fla.1964). Similarly, I have little difficulty rejecting appellant's challenge to the use of his pre-trial statements at trial, allegedly in violation of Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16 L.Ed.2d 694 (1966). This issue, not raised at appellant's trial or asserted on direct review of his conviction and sentence, is foreclosed in this collateral proceeding under our contemporaneous objection rule. State v. Matera, 266 So.2d 661 (Fla.1972); and see Wainwright v. Sykes, 433 U.S. 72, 97 S.Ct. 2497, 53 L.Ed.2d 594 (1977). To the assertion that a different rule should apply in death penalty cases, I would observe that we have already considered and rejected this contention. Gibson v. State, 351 So.2d 948 (Fla. opinion filed July 28, 1977) (pending on rehearing).

Appellant's only other ground asserted for relief attacks the composition of the jury which imposed his death sentence as violating Witherspoon standards of objectivity. The first obstacle to be overcome in order to assert this challenge is appellant's knowing waiver. If an alleged Witherspoon infirmity can ever be waived, the state contends that it was waived here by trial counsel's express directive that the court reporter not transcribe voir dire examination for the record on appeal and by his failure to assign the matter as error on direct appeal of appellant's conviction and sentence. I have concluded, along with my colleagues, that an alleged Witherspoon infirmity can be waived, and that it was in fact waived in this case.

This Court has expressly held in Richardson v. State, 247 So.2d 296 (Fla.1971), that an alleged Witherspoon problem could be waived. Appellant suggests that waiver is nonetheless constitutionally improper on the basis of language in the Witherspoon opinion and recent decisions applying its principles.[FN5] Appellant's contention again hinges on the premise that death is different. Nonetheless, nothing in the constitution of the United States or Florida suggests that even the most fundamental rights cannot be knowingly waived during the course of a capital or other type of criminal proceeding. Barker v. Wingo, 407 U.S. 514, 92 S.Ct. 2182, 33 L.Ed.2d 101 (1972).

FN5. E. g., Davis v. Georgia, 429 U.S. 122, 97 S.Ct. 399, 50 L.Ed.2d 339 (1977); Mathis v. Alabama, 403 U.S. 946, 91 S.Ct. 2278, 29 L.Ed.2d 855 (1971); Wigglesworth v. Ohio, 403 U.S. 947, 91 S.Ct. 2284, 29 L.Ed.2d 857 (1971); Owens v. State, 233 Ga. 869, 214 S.E.2d 173 (1975). None of these cases addressed the issue of whether an alleged Witherspoon violation can be waived. HATCHETT, Justice, concurring specially.

I join in the denial of the Motion for Stay and the denial of the Appellant's Motion to Vacate and Set Aside or Correct Sentence only because I am bound by duty to uphold the law as defined by this Court and the United States Supreme Court. If I alone were determining the constitutionality of Section 921.141, Florida Statutes, I would find the statute unconstitutional on its face. But that question has been decided to the contrary by the United States Supreme Court in Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242, 96 S.Ct. 2960, 49 L.Ed.2d 913 (1976) and by this Court in State v. Dixon, 283 So.2d 1 (Fla.1973). Now that the question of the statute's application is clearly presented, I would also find Section 921.141, Florida Statutes to be unconstitutional as applied. A review of the cases that have come before this Court indicate that the death sentence is imposed irregularly, unpredictably, and follows no discernable pattern. Swan v. State, 322 So.2d 485 (Fla.1975), (victim brutally beaten and tied in such a manner that struggling to free herself would choke her); Halliwell v. State, 323 So.2d 557 (1975) (victim beaten to death with an iron bar and corpse cut into pieces); Tedder v. State, 322 So.2d 908 (Fla.1975) victim shot, perpetrator refused to allow anyone the *88 right to aid her as she bled to death). In all of these cases this Court reduced the death sentences to life imprisonment.[FN1] It is apparent to me that the death penalty under the Florida statutory scheme is being administered in an arbitrary and capricious manner inconsistent with the premises underlying Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 92 S.Ct. 2726, 33 L.Ed.2d 346 (1972); State v. Dixon, supra, and Proffitt v. Florida, supra. But this issue was apparently foreclosed by the United States Supreme Court in its decision in Proffitt.

FN1. McCaskill, Williams v. State, 344 So.2d 1276 (Fla.1977).Burch v. State, 343 So.2d 831 (Fla.1977).Huckaby v. State, 343 So.2d 29 (Fla.1977).Chambers v. State, 339 So.2d 204 (Fla.1976).Jones v. State, 332 So.2d 615 (Fla.1976).Provence v. State, 337 So.2d 783 (Fla.1976).Thompson v. State, 328 So.2d 1 (Fla.1976).Obviously this Court has had great difficulty in applying the present statute. The aggravating and mitigating circumstances enumerated in Section 921.141(5), (6) are so ill defined and vague as to escape reasonable and consistent application. Although the Constitution provides in Article V, Section 3(b)(2) that the Supreme Court “shall hear appeals from final judgments and orders of trial courts imposing life imprisonment” the Legislature has never activated this provision. Consequently, the Florida Supreme Court only reviews cases in which the death penalty is imposed. This Court is without authority to review those cases where the trial judge imposes a sentence of life imprisonment, regardless of the jury's recommendation of life or death. This situation deprives this Court of the opportunity to determine whether death is being imposed evenhandedly. Herein lies the breeding grounds for all of the horrors condemned by Furman.

Two men charged for the same first degree murder, tried in the same courtroom, at the same time, before the same judge and jury, could upon conviction, conceivably be sentenced, one to death, and the other to life, through the exercise of the unfettered discretion afforded the trial judge under our statute. The one receiving the life imprisonment sentence would have his case reviewed by a District Court of Appeal which is powerless to review the appropriateness of the sentence. Therefore, in that situation, the trial judge's discretion as to sentence is never really reviewed. This statutory scheme insulates the discretion exercised by the trial court from review by any higher court, including the Supreme Court of Florida which is charged with the duty of insuring that the death penalty is imposed strictly in accordance with the dictates of Section 921.141, Florida Statutes, and that those convicted of murder receive equal treatment under the law.