Executed February 29, 2012 06:22 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Texas

6th murderer executed in U.S. in 2012

1283rd murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

2nd murderer executed in Texas in 2012

479th murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(6) |

George Rivas H / M / 30 - 41 |

Aubrey Hawkins OFFICER W / M / 29 |

Rivas, then 30, escaped from the maximum-security Connally Prison Unit in south Texas, where he was serving a life sentence for multiple counts of aggravated kidnapping, aggravated robbery, and burglary. Rivas made the escape with six other prisoners - Patrick Murphy, 39; Donald Newbury, 38; Michael Rodriguez, 38; Joseph Garcia, 29; Randy Halprin, 23; and Larry Harper. The men overpowered prison workers and took their clothes, stole guns from the armory, and escaped in a prison pickup that had been modified with a false bottom. The escapees, who committed a string of crimes as they trekked northward through Texas, became known nationally as the "Texas Seven." They had left a note behind at the scene of their escape reading, "You haven't heard the last of us yet."

On 24 December, the escapees went to an Oshman's sporting goods store in Irving. Armed with weapons and two-way radios, they overpowered store employees masquerading as Oshman's security guards. While this was happening, Misty Wright, the girlfriend of one of the employees, was waiting outside and saw the employees inside raising their hands over her head. Eventually police were called. Irving police officer Aubrey Hawkins was the first officer to arrive at the scene. He drove directly to the back of the store, where he was shot eleven times. Evidence presented at trial showed that he was shot with at least five different guns from at least three directions, and that he died immediately. Some of the escapees pulled Hawkins' body from his police vehicle and took his sidearm. Rivas then ran over Hawkins in Ferris's Explorer, dragging his body approximately ten feet. Rivas was shot during the barrage of gunfire. The escapees got away with over $70,000 in cash, 44 firearms, ammunition, camping equipment, and the employees' wallets and jewelry. The Texas Seven committed three more armed robberies as they made their way northward, but were eventually captured in a Colorado RV park with the help of "America's Most Wanted." Hawkins' gun, as well as guns and merchandise stolen from Oshman's, were found in the mens' possession at the time of their arrest. Rivas signed a written confession. Rivas was the admitted leader of the group, planned the escape, and shot Hawkins. Rivas testified that he only shot at Hawkins because Hawkins was reaching for his gun. He said he knew Hawkins would be wearing a bulletproof vest, so he deliberately shot him in the chest, so as to subdue him, rather than kill him. He testified that he did not know he had run over Hawkins until he heard the evidence at trial. At his punishment hearing, Rivas asked the jury to sentence him to death.

All five of the other surviving escapees were also convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death. Rodriguez was executed in 2008 after dropping his appeals. Newbury had been scheduled for execution earlier this month until the United States Supreme Court intervened and issued a stay. Murphy, Garcia, and Halprin are on death row and have yet to receive execution dates. Rodriguez's father, Raul, pleaded guilty to helping the prisoners escape.

Citations:

Rivas v. Thaler, 432 Fed.Appx. 395 (5th Cir. 2011). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Texas no longer offers a special "last meal" to condemned inmates. Instead, the inmate is offered the same meal served to the rest of the unit.

Final/Last Words:

"First of all, for the Aubrey Hawkins family, I do apologize for everything that happened. Not because I'm here, but for closure in your hearts. I really do believe you deserve that." Rivas then expressed love to his wife, sister, son, other friends and family, and his fellow death row inmates. "Thank you to the people involved and the courtesy of the officers. I am grateful for everything in my life. To my wife, take care of yourself. I will be waiting for you. I love you. God bless. I am ready to go."

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Rivas)

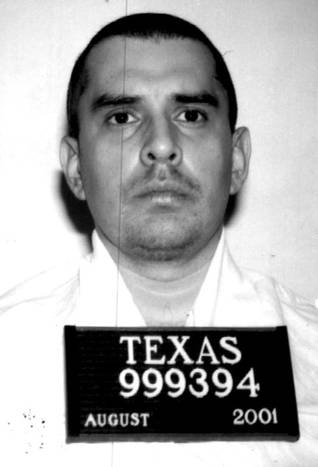

Rivas, George

Date of Birth: 5/6/1970

DR#: 999394

Date Received: 8/29/2001

Education: 12 years

Occupation: clerk, cook, laborer

Date of Offense: 12/24/2000

County of Offense: Dallas

Native County: El Paso

Race: Hispanic

Gender: Male

Hair Color: Black

Eye Color: Brown

Height: 5' 10"

Weight: 142

Prior Prison Record: #702267 on a life sentence from El Paso County for 13 counts of aggravated kidnapping with a deadly weapon, 4 counts of aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon, and one count of burglary of a habitation. Was serving the life sentence and had escaped from TDCJ when committing the present offense.

Summary of incident:While on escape from TDCJ, Rivas and 6 co-defendants robbed a sporting goods store at gunpoint. An Irving police officer was murdered outside the store as Rivas and co-defendants left the scene.

Co-Defendants: Michael Rodriguez (sentenced to death); Donald Newberry (sentenced to death); Randy Halprin; Patrick Murphy, Jr.; Joseph Garcia; Larry Harper.

Friday, February 24, 2012

Media Advisory: George Rivas scheduled for execution

AUSTIN – Pursuant to an order entered by the 283rd District Court in Dallas County, George Rivas is scheduled for execution after 6 p.m. on February 29, 2012. In 2001, a Dallas County jury found Rivas guilty of murdering Aubrey Hawkins, an officer with the Irving Police Department who was serving in the line of duty at the time of his murder.

FACTS OF THE CASE

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, citing facts adopted by a federal district court, described the murder of Officer Hawkins as follows: On December 13, 2000, Rivas and six of his fellow inmates escaped from the Connally Prison Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. The group included Rivas, Joseph Garcia, Randy Halprin, Larry Harper, Patrick Murphy, Donald Newbury, and Michael Rodriguez.

Eleven days after their escape, the [escapees] initiated a Christmas Eve robbery of the Oshman’s Superstore in Irving, Texas, that ended with the death of Irving police officer Aubrey Hawkins. Armed with weapons and two-way radios, Garcia, Halprin, Newbury, and Rodriguez entered the store just prior to closing pretending to be customers, while Rivas and Harper masqueraded as Oshman’s security guards. Murphy, the seventh member of the group, waited in a truck outside the store, serving as a lookout and checking police radio frequencies.

Rivas and Harper explained to the store managers that they were investigating a theft at another Oshman’s and asked that a manager bring the store's employees together to look at a photo spread. Meanwhile, the other men moved throughout the store collecting merchandise. Once the employees were gathered together, Rivas brandished a gun and told everyone of his intent to rob the store. Rivas then instructed the men in his group to take the Oshman’s employees to the store’s breakroom and tie them up. While this was happening, Rivas told store manager Wesley Ferris to open the store's gun vault, safe, and cash registers. Rivas repeatedly warned Ferris not to try anything or he and the others would be shot. Afterwards, Rivas left Ferris with the employees in the breakroom, took Ferris’s car keys, exited the Oshman’s through the main front entrance, and drove Ferris’s Ford Explorer around the store to the loading dock located in the back.

Altogether, the [escapees] stole over $70,000 in cash, forty-four firearms, ammunition, and other goods from the store, in addition to the employees’ jewelry and wallets. During the robbery, Misty Wright, a girlfriend of one of the Oshman’s employees, waited in her car outside the store and saw the employees inside raising their hands over their heads. Wright called a friend who joined her in her car. The two saw Rivas exit the Oshman’s and drive Ferris’s Ford Explorer to the back of the store. Wright and her friend then fled the parking lot and called the police from a nearby restaurant. Rivas, who had seen Wright and her friend driving away in haste, used his two-way radio to warn the others, and he directed them to get to the back of the store. Within minutes, Murphy radioed the group, alerting them to a police vehicle he had seen entering the Oshman’s parking lot.

The police dispatcher who took Wright’s emergency call sent four officers to the scene. Irving police officer Aubrey Hawkins was the first to arrive. Hawkins drove directly through the parking lot to the back of the store, where he was shot eleven times by various members of the [escapees]. Evidence at trial established that at least five different guns fired at Hawkins from at least three directions in less than a minute and that he died immediately. Some of the escapees pulled Hawkins from the police vehicle and took his sidearm. Moments later, Rivas ran over Hawkins in the Ford Explorer, dragging his body approximately ten feet. According to Rivas, he did not know he had run over Hawkins until he heard the evidence at trial.

During his trial, Rivas testified that as he approached Hawkins's vehicle, he thought he saw the officer reaching for his gun and that [Rivas] only shot Hawkins in an attempt to subdue him. Rivas claimed that he purposefully shot the officer in the chest because he knew Hawkins would be wearing a bulletproof vest. In addition, Rivas said that he shot at Hawkins four times in response to what he thought were shots fired by Hawkins. The evidence showed that Rivas was, in fact, shot during the period of intense gunfire.

Following the robbery, the [seven inmates] escaped to Colorado where someone identified them and notified the Federal Bureau of Investigation. All of the men were arrested, except Harper, who committed suicide before authorities could apprehend him. On the day of his arrest, Rivas was interviewed by police and, after waiving his Miranda rights, signed a 21-page written confession. During searches of an RV and another vehicle the [escapees] had been using, authorities recovered Hawkins’s gun, as well as guns and merchandise stolen from the Oshman’s in Irving, Texas.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

On February 7, 2001, a Dallas County grand jury indicted Rivas for murdering Irving police officer Aubrey Hawkins. Because Rivas was aware at the time of the murder that the victim was a peace officer acting in the lawful discharge of an official duty, Rivas was charged with capital murder.

In August 2001, a Dallas County jury found Rivas guilty of murdering Officer Aubrey Hawkins while he served in the line of duty. After the jury recommended capital punishment, the court sentenced Rivas to death by lethal injection.

On June 23, 2004, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals rejected Rivas’s direct appeal and affirmed his conviction and sentence. The appeals court denied Rivas’s motion for rehearing on September 22, 2004.

On February 22, 2005, the Supreme Court of the United States rejected Rivas’s direct appeal when it denied his petition for certiorari.

After exhausting his direct appeals, Rivas sought to appeal his conviction and sentence by filing an application for a state writ of habeas corpus with the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. On February 16, 2006, the high court denied Rivas’s application for state habeas relief.

On February 13, 2007, Rivas attempted to appeal his conviction and sentence in the federal district court for the Northern District of Texas. The federal district court denied his petition for federal writ of habeas corpus on March 29, 2010.

On July 14, 2011, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit rejected Rivas’s appeal when it affirmed the federal district court’s order denying Rivas a federal writ of habeas corpus.

On December 12, 2011, the United States Supreme Court rejected Rivas’s appeal a second time when it denied his petition for a writ of certiorari.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

RGeorge Rivas, 41, was executed by lethal injection on 29 February 2012 in Huntsville, Texas for the murder of a police officer while on escape from prison.

On 13 December 2000, Rivas, then 30, escaped from the maximum-security Connally Prison Unit in south Texas, where he was serving a life sentence for multiple counts of aggravated kidnapping, aggravated robbery, and burglary. Rivas made the escape with six other prisoners - Patrick Murphy, 39; Donald Newbury, 38; Michael Rodriguez, 38; Joseph Garcia, 29; Randy Halprin, 23; and Larry Harper. The men overpowered prison workers and took their clothes, stole guns from the armory, and escaped in a prison pickup that had been modified with a false bottom. They then drove to a nearby store, where Rodriguez's father had left another truck for them.

The escapees, who committed a string of crimes as they trekked northward through Texas, became known nationally as the "Texas Seven." They had left a note behind at the scene of their escape reading, "You haven't heard the last of us yet."

On 19 December, the group robbed a Radio Shack and an Auto Zone in Houston. They also obtained security officers' uniforms from a used clothing store.

On 24 December, the escapees went to an Oshman's sporting goods store in Irving. Armed with weapons and two-way radios, Garcia, Halprin, Newbury and Rodriguez entered the store just prior to closing. Rivas and Harper also entered, masquerading as Oshman's security guards. Murphy waited in a truck outside the store and monitored the police radio frequencies.

Rivas and Harper told the store managers that they were investigating a theft at another Oshman's and asked that all the store's employees be brought together to look at a photo spread. The other men, meanwhile, went through the store, gathering merchandise. Once the employees were gathered together, Rivas drew a gun and announced that he was robbing the store. He instructed the other men to tie the employees up in the store's break room. He also ordered store manager Wesley Ferris to open the store's gun vault, safe, and cash registers, repeatedly warning him that he would be shot if he resisted. Rivas then took Ferris's keys and left him in the break room with the other employees.

While this was happening, Misty Wright, the girlfriend of one of the employees, was waiting outside in her car for the store to close. She saw the employees inside raising their hands over her head and called a friend, who joined her in her car.

Rivas then exited the store through the front entrance and drove Ferris's Ford Explorer around to the loading dock in the back. Wright and her friend saw this and drove quickly to a nearby restaurant to phone the police. Rivas noticed Wright driving away and warned the others on his radio, directing them to move to the back of the store. Within minutes, Murphy radioed the group to alert them to a police vehicle he saw entering the Oshman's parking lot.

Irving police officer Aubrey Hawkins was the first officer to arrive at the scene. He drove directly to the back of the store, where he was shot eleven times. Evidence presented at trial showed that he was shot with at least five different guns from at least three directions, and that he died immediately.

Some of the escapees pulled Hawkins' body from his police vehicle and took his sidearm. Rivas then ran over Hawkins in Ferris's Explorer, dragging his body approximately ten feet.

Rivas was shot during the barrage of gunfire.

The escapees got away with over $70,000 in cash, 44 firearms, ammunition, camping equipment, and the employees' wallets and jewelry.

The Texas Seven committed three more armed robberies as they made their way northward. Rivas bought a recreational vehicle with the stolen money. Posing as a lawman, he also bought body armor from a police supply store.

The men lived in an RV park near Colorado Springs, pretending to be missionaries, for about three weeks. A neighbor at the RV park recognized them after seeing the Texas Seven case profiled on television's "America's Most Wanted" and called police. On 22 January 2001, a SWAT team surrounded the gang in the trailer park. When capture was imminent, Larry Harper killed himself. Rivas, Rodriguez, Garcia, and Halprin were captured. Murphy and Newbury evaded capture that day. Two days later, however, they were cornered at a hotel and eventually surrendered.

Hawkins' gun, as well as guns and merchandise stolen from Oshman's, were found in the mens' possession at the time of their arrest. Rivas signed a written confession.

At his trial, jurors were told that Rivas was the leader of the escapees. He had planned their escape from the Connally Unit as well as the robbery of the Oshman's in Irving.

Rivas testified that he only shot at Hawkins because Hawkins was reaching for his gun. He said he knew Hawkins would be wearing a bulletproof vest, so he deliberately shot him in the chest, so as to subdue him, rather than kill him. He testified that he did not know he had run over Hawkins until he heard the evidence at trial.

At his punishment hearing, Rivas asked the jury to sentence him to death.

At the time of his escape, Rivas was serving a life sentence for 13 counts of aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon, 4 counts of aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon, and one count of burglary of a habitation.

A jury convicted Rivas of capital murder in August 2001 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence in June 2004. Even though Rivas got the death sentence he asked for, he continued to file appeals in state and federal courts and to the state clemency board for eight more years, all the way up to the week of his death. All of them were denied.

All five of the other surviving escapees were also convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death. Rodriguez was executed in 2008 after dropping his appeals. Newbury had been scheduled for execution earlier this month until the United States Supreme Court intervened and issued a stay. Murphy, Garcia, and Halprin are on death row and have yet to receive execution dates. Rodriguez's father, Raul, pleaded guilty to helping the prisoners escape.

From death row, Rivas described his upcoming execution to a reporter as "bittersweet". "Bitter because I hurt for my family, for them," he said, "Sweet because it's almost over."

Rivas said that prison was a constant reminder of the wrong decisions he made in life. He said he thought of Hawkins frequently, especially every Christmas. He said he regretted that "I didn't find Christ sooner."

In the interview, Rivas said that he had always tried not to hurt anyone. He said chose the other members of the escape gang because he believed they weren't likely to hurt anyone, and that they all went to great lengths to avoid hurting corrections officers.

"Quite honestly, if we wanted to be brutal, we had sledgehammers. We had axes," he said. "The reason every single one of them is alive is because we didn't want to hurt them."

Rivas said Hawkins' killing was the first time "that I had actually used a weapon on a person."

Toby Shook, former Dallas County assistant district attorney, dismissed Rivas's self-portrayal as an outlaw with a conscience. "He's quite the storyteller," Shook said.

No one from Hawkins' family attended Rivas's execution. The witnesses for the victim included Shook and four of Hawkins' former police colleagues. A Canadian woman named Cheri, who Rivas recently married by proxy, also attended.

"First of all, for the Aubrey Hawkins family, I do apologize for everything that happened," Rivas said in his last statement. "Not because I'm here, but for closure in your hearts. I really do believe you deserve that." Rivas then expressed love to his wife, sister, son, other friends and family, and his fellow death row inmates.

"Thank you to the people involved and the courtesy of the officers," he said in conclusion. "I am grateful for everything in my life. To my wife, take care of yourself. I will be waiting for you. I love you. God bless. I am ready to go." The lethal injection was then started. He was pronounced dead at 6:22 p.m.

(Reuters) - A Texas man who confessed to being the ringleader of a ruthless band of murderers and rapists was executed on Wednesday, hours after Arizona put another man to death for killing his adoptive mother.

George Rivas, 41, was pronounced dead at 6:22 p.m. at a prison in Huntsville, Texas, state officials said.

Rivas was executed for his role in the "Texas Seven" gang's murder of police officer Aubrey Hawkins outside an Oshman's Superstore on Christmas Eve 2000 in Irving, next to Dallas.

Rivas was the confessed ringleader of the group, a band of convicted robbers, rapists and murderers who broke out of a maximum security prison in Karnes County, southeast of San Antonio on December 13, 2000. At the time, Rivas was serving 17 life sentences for several crimes including aggravated kidnapping, according to the Texas Attorney General's office.

Earlier on Wednesday, Arizona executed 63-year-old convicted murderer Robert Henry Moormann.

"Leader of ‘Texas 7’ put to death," by Michael Graczyk. (Associated Press February 29, 2012)

HUNTSVILLE — The leader of the fugitive gang known as the “Texas 7” was executed Wednesday for killing a suburban Dallas police officer during a robbery 11 years ago after organizing and pulling off Texas’ biggest prison break.

George Rivas, 41, from El Paso, received lethal injection for gunning down Aubrey Hawkins, a 29-year-old Irving police officer who interrupted the gang’s holdup of a sporting goods store on Christmas Eve in 2000. The seven inmates had fled a South Texas prison about two weeks earlier.

The gang was caught in Colorado about a month after the officer’s death. One committed suicide rather than be arrested. Rivas and five others with lengthy sentences who bolted with him were returned to Texas where they separately were convicted of capital murder and sentenced to die.

Rivas became the second of the group executed.

“I do apologize for everything that happened. Not because I’m here, but for closure in your hearts,” Rivas said Wednesday evening in a statement intended for Hawkins’ family. “I really do believe you deserve that.”

The slain officer’s relatives were absent, but four officers who worked with him and the district attorney who prosecuted the case attended on his family’s behalf. They stood in the death chamber watching through a window just a few feet from Rivas.

The inmate thanked his friends who were watching through another window and said he loved them. A Canadian woman whom Rivas recently married by proxy, also looked on.

“I am grateful for everything in my life,” Rivas said. “To my wife, I will be waiting for you.”

Ten minutes later, at 6:22 p.m. CST, he was pronounced dead.

More than two dozen police officers in uniforms stood quietly in a line outside the Huntsville prison during the execution, then walked in unison to stand behind the state criminal justice spokesman as he announced Rivas’ death.

Texas’ parole board voted 7-0 this week to reject a clemency petition for Rivas. No 11th-hour appeals were made to try to head off the execution, the second this year in the nation’s most active death penalty state.

Rivas and accomplices he handpicked for the escape broke out of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice Connally Unit, about an hour south of San Antonio, on Dec. 13, 2000. They overpowered workers, stole their clothes, broke into the prison armory for weapons and drove off in a prison truck.

They left behind an ominous note: “You haven’t heard the last of us yet.”

While out of prison, they supported themselves by committing robberies.

Hawkins was shot 11 times and run over with a stolen SUV driven by Rivas as the gang held up a sporting goods store closing on the holiday eve. They drove off with loot that included $70,000 in cash, 44 firearms and ammunition for the guns.

They were arrested a month later in Colorado, ending a six-week nationwide manhunt. One of the fugitives, Larry Harper, committed suicide as officers closed in.

In 2008, accomplice Michael Rodriguez, 45, who at the time of the breakout had a life term for arranging the slaying of his wife, ordered his appeals dropped and was executed. The four others remain on death row awaiting the outcome of court appeals.

“Today is not about George Rivas,” said Toby Shook, the former Dallas County assistant district attorney who prosecuted Rivas and the others for Hawkins’ death. “Today is about justice for Aubrey Hawkins and Aubrey’s fellow police officers.”

Rivas planned the escape while serving 17 life sentences for aggravated kidnapping and aggravated robbery and another life sentence for burglary.

One of his trial lawyers, Wayne Huff, has said Rivas picked accomplices for the breakout “who probably were more dangerous than he was” and failed to consider they might get caught doing robberies.

“When that cop pulled up, no one knew what to do,” Huff said, calling the officer’s slaying “just a tragic situation.”

Rivas and two other members of the fugitive gang were arrested at a convenience store near a trailer park in Woodland Park, Colo. Two others were in a motor home at the trailer park, where Harper shot himself to death. The last two were apprehended at a motel in Colorado Springs, Colo.

The men had told the people who ran the RV park they were Christian missionaries from Texas, but a neighbor recognized them as the case was profiled on the “America’s Most Wanted” TV show and called police.

The four “Texas 7” members still awaiting execution are Patrick Murphy Jr. 49; Joseph Garcia, 40; Randy Halprin, 34; and Donald Newbury, 49. Newbury was set for injection in early February but was spared, at least temporarily, by a U.S. Supreme Court order.

"Leader of 'Texas 7' prison-break gang put to death," by Michael Graczyk. (AP February 29, 2012)

HUNTSVILLE, Texas (AP) — The leader of the fugitive gang known as the "Texas 7" was executed Wednesday for killing a suburban Dallas police officer during a robbery 11 years ago after organizing and pulling off Texas' biggest prison break.

George Rivas, 41, from El Paso, received lethal injection for gunning down Aubrey Hawkins, a 29-year-old Irving police officer who interrupted the gang's holdup of a sporting goods store on Christmas Eve in 2000. The seven inmates had fled a South Texas prison about two weeks earlier.

The gang was caught in Colorado about a month after the officer's death. One committed suicide rather than be arrested. Rivas and five others with lengthy sentences who bolted with him were returned to Texas where they separately were convicted of capital murder and sentenced to die.

Rivas became the second of the group executed.

"I do apologize for everything that happened. Not because I'm here, but for closure in your hearts," Rivas said Wednesday evening in a statement intended for Hawkins' family. "I really do believe you deserve that."

The slain officer's relatives were absent, but four officers who worked with him and the district attorney who prosecuted the case attended on his family's behalf. They stood in the death chamber watching through a window just a few feet from Rivas.

The inmate thanked his friends who were watching through another window and said he loved them. A Canadian woman whom Rivas recently married by proxy, also looked on.

"I am grateful for everything in my life," Rivas said. "To my wife, I will be waiting for you."

Ten minutes later, at 6:22 p.m. CST, he was pronounced dead.

More than two dozen police officers in uniforms stood quietly in a line outside the Huntsville prison during the execution, then walked in unison to stand behind the state criminal justice spokesman as he announced Rivas' death.

Texas' parole board voted 7-0 this week to reject a clemency petition for Rivas. No 11th-hour appeals were made to try to head off the execution, the second this year in the nation's most active death penalty state.

In 2008, accomplice Michael Rodriguez, 45, who at the time of the breakout had a life term for arranging the slaying of his wife, ordered his appeals dropped and was executed. The four others remain on death row awaiting the outcome of court appeals.

"Today is not about George Rivas," said Toby Shook, the former Dallas County assistant district attorney who prosecuted Rivas and the others for Hawkins' death. "Today is about justice for Aubrey Hawkins and Aubrey's fellow police officers."

Rivas planned the escape while serving 17 life sentences for aggravated kidnapping and aggravated robbery and another life sentence for burglary.

One of his trial lawyers, Wayne Huff, has said Rivas picked accomplices for the breakout "who probably were more dangerous than he was" and failed to consider they might get caught doing robberies.

"When that cop pulled up, no one knew what to do," Huff said, calling the officer's slaying "just a tragic situation."

Rivas and two other members of the fugitive gang were arrested at a convenience store near a trailer park in Woodland Park, Colo. Two others were in a motor home at the trailer park, where Harper shot himself to death. The last two were apprehended at a motel in Colorado Springs, Colo.

The men had told the people who ran the RV park they were Christian missionaries from Texas, but a neighbor recognized them as the case was profiled on the "America's Most Wanted" TV show and called police.

The four "Texas 7" members still awaiting execution are Patrick Murphy Jr. 49; Joseph Garcia, 40; Randy Halprin, 34; and Donald Newbury, 49. Newbury was set for injection in early February but was spared, at least temporarily, by a U.S. Supreme Court order.

"El Pasoan executed Wednesday once called "one of the most dangerous men in El Paso. by Daniel Borunda.

Posted: 02/29/2012 01:08:46 PM MST - George Rivas, a convicted armed robber and murderer once described as the "one of the most dangerous men in El Paso," is scheduled to die by lethal injection this evening in Huntsville.

Rivas, 41, was given a death sentence after being convicted in the murder of Irving police officer Aubrey Hawkins during a store robbery on Christmas Eve 2000 while leading a group of prison escapees known as the "Texas Seven."

Rivas had escaped from prison while serving 17 life prison terms after being convicted in 1994 of heavily-armed, takeover-style robberies of a Toys "R" Us store and an Oshman's Sporting Goods Store in El Paso.

The manhunt for the seven fugitives had grabbed the nation's attention after they broke out of the Texas prison system's Connally Unit in Kenedy.

Rivas has been described by some who knew him as polite, kind and charismatic, yet others said he was cunning, conniving and a master manipulator who could get others to do his dirty work.

After his parents divorced, Rivas was raised in the Lower Valley by his grandmother, Anita Potter, whom he referred to as "mom," according to archives from the El Paso Times, El Paso Herald-Post and The Associated Press.

When Rivas was convicted in the armed robberies in El Paso, his grandmother asked jurors to give him probation.

"He's always been a good-hearted person. All this mess has messed up his life. As long as there's life, there's hope," Potter told the jury.

Rivas was a 1988 graduate of Ysleta High School. It took him five years to graduate mostly because he was frequently absent.

A former counselor at Ysleta remembered Rivas as a polite young man who had an interest in law enforcement. Other faculty members described him as a young man who could have been student body president but instead thought the rules didn't apply to him.

Rivas' involvement in violent crime began before he graduated from high school.

A mistrial was declared during a trial for the aggravated robbery of a Payless Shoe Source store in 1987. The robberies in a few years would evolve into highly-planned, takeover-style capers.

While on probation for a home burglary, Rivas took part in the April 1993 robbery of an El Paso Oshman's Sporting Goods Store at what was then called Bassett Center. During that robbery, Rivas and two men used walkie-talkies to communicate and employees were handcuffed while the men robbed the store of guns and money.

On May 26, 1993, the gang struck again with a similar robbery at a Toys "R" Us store near Sunland Park Mall in West El Paso.

Rivas and two men, Fabien Gutierrez and Giovanni Novella, entered the store disguised with fake beards and Rivas wore a blond wig. The men used walkie-talkies to communicate, handcuffed store workers and herded them into a room.

But the robbery didn't go as planned. Police showed up and the robbery turned into a hostage situation lasting almost 3 1/2 hours and involving more than 100 officers from various law-enforcement agencies.

Eventually, the El Paso police SWAT team slipped into the store, rescued the hostages and arrested Rivas and the other two men.

During his trial, Rivas claimed he was an innocent bystander who didn't know the other two men were going to rob the toy store until they handed him a gun and claimed the store manager was in on the robbery. The jury didn't buy it.

"George Rivas is one of the most dangerous men in El Paso. He is one of the most dangerous men in Texas," then-First Assistant District Attorney Marcos Lizarraga said during the Rivas trial in 1994.

During the trial, a report by Dr. Richard Coons, a board-certified psychologist, described Rivas as a prolific, confident and arrogant criminal mastermind who was "physically, mentally and morally dangerous and will continue to be so in 15 years."

Authorities suspected Rivas of taking part in other robberies, including a 1993 heist at a Furr's supermarket. Rivas was convicted of eight counts of aggravated kidnapping and two counts of aggravated robbery. He was sentenced to 17 life terms.

County records show Rivas was married at the time of his conviction. He divorced in 1999.

Rivas would later testify that while in prison, he gained the trust of supervisors by curbing tool thefts and was then allowed to pick some of the men who would become his fellow escapees to work in the prison maintenance department.

On Dec. 13, 2000, Rivas and other inmates used homemade knives called shanks to overpower prison workers and escape. The manhunt for the "Texas Seven" would become one of the most infamous in state history.

On Dec. 24, 2000, Irving police officer Aubrey Hawkins was shot and killed by the gang of escapees as they were robbing a sporting goods store in suburban Dallas. The robbery was similar to those that Rivas was convicted of committing in El Paso.

Hawkins was shot 11 times, some of the rounds were fired by Rivas, and run over by a sport utility vehicle driven by Rivas.

A nationwide manhunt ended when the escapees were captured in Colorado. Larry Harper, who was also from El Paso, committed suicide rather than be captured.

During his 2001 trial in Dallas for Hawkins' death, Rivas detailed the escape and testified that he did not want to hurt anyone. Rivas said the motive for the escape was simple.

"I wasn't going to die an old man in prison," Rivas said. Rivas and the other inmates all received death sentences for the murder of Hawkins.

The Texas Seven was a group of prisoners who escaped from the John Connally Unit near Kenedy, Texas, on December 13, 2000. They were apprehended a little more than a month later, on January 21–23, 2001, as a direct result of the television show America's Most Wanted.

Members

The group was composed of the following Texas state prisoners:

Joseph C. Garcia (born on November 6, 1971, San Antonio, Texas), 29 at the time of the escape,[1]

Randy Ethan Halprin (born September 13, 1977, McKinney, Texas), 23 at the time of the escape,[2]

Larry James Harper (September 10, 1963, Danville, Illinois – January 22, 2001, Woodland Park, Colorado), 37 at the time of the escape, 37 at the time of death via suicide and was not captured by law enforcement,[3]

Patrick Henry Murphy, Jr. (born October 3, 1961, Dallas, Texas), 39 at the time of the escape,[4][5]

Donald Keith Newbury (born May 18, 1962, Albuquerque, New Mexico), 38 at the time of the escape,[6]

George Rivas (May 6, 1970, El Paso, Texas – February 29, 2012, Huntsville, Texas), 30 at the time of the escape, 41 at time of death, leader, executed,[7]

Michael Anthony Rodriguez (October 29, 1962, San Antonio, Texas – August 14, 2008, Huntsville, Texas, 38 at the time of the escape, 45 at the time of death), executed.[8]

Escape

On December 13, 2000, the seven carried out an elaborate scheme and escaped from the John B. Connally Unit, a maximum-security state prison near the South Texas city of Kenedy.

At the time of the breakout, the reported ringleader of the Texas Seven, 30-year-old George Rivas, was serving 18 consecutive 15-to-life sentences. Michael Anthony Rodriguez, 38, was serving a 99-to-life term, while Larry James Harper, 37, Joseph Garcia and Patrick Henry Murphy, Jr., 39, were all serving 50 year sentences. Donald Keith Newbury, the member with the longest rap sheet of the group, was serving a 99-year sentence, and the youngest member, Randy Halprin, 23, was serving a 30-year sentence for injury to a child.

Using several well-planned ploys, the seven convicts overpowered and restrained nine civilian maintenance supervisors, four correctional officers and three uninvolved inmates at approximately 11:20 a.m. The escape occurred during the slowest period of the day (during lunch and at count time) when there was less surveillance of certain locations, such as the maintenance area. Most of these plans involved one of the offenders calling someone over, while another hit the unsuspecting person on the head from behind. Once each victim was subdued, the offenders removed some of his clothing, tied him up, gagged him and placed him in an electrical room behind a locked door.

The attackers stole clothing, credit cards, and identification from their victims. The group also impersonated prison officers on the phone and created false stories to ward off suspicion from authorities.

After that, three of the group made their way to the back gate of the prison, some disguised in stolen civilian clothing. They pretended to be there to install video monitors. One guard at the gatehouse was subdued, and the trio raided the guard tower and stole numerous weapons. Meanwhile, the four offenders who stayed behind made calls to the prison tower guards to distract them. They then stole a prison maintenance pick-up truck, which they drove to the back gate of the prison, picked up their cohorts, and drove away from the prison.

Gary C. King, who wrote a Crime Library article about the seven, stated that some people compared this breakout to the breakout from Alcatraz that took place decades earlier.[9]

Crime spree

Aubrey Hawkins, the police officer killed by the Texas Seven.

The white prison truck was found in the parking lot of the Wal-Mart in Kenedy, Texas. The Texas 7 first went into San Antonio right after breaking out of the complex.[10] Realizing that they were running out of funds, they robbed a Radio Shack in Pearland, Texas the next day on December 14.[11]

On December 19, four of the members checked into an Econo Lodge motel in Farmers Branch, Texas (under assumed names).[11] They decided to rob an Oshman's Sporting Goods in nearby Irving, Texas. On December 24, 2000, they held up the store and stole at least 40 guns and sets of ammunition. An off-duty employee standing outside of the store noticed the commotion inside and called police.[12] Irving policeman Aubrey Hawkins responded to the call, arrived on the scene and was almost immediately ambushed; his autopsy later showed that he had sustained eleven gunshots and had been run over by the fleeing gang. Hawkins died at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas shortly after his arrival.[13]

After Officer Hawkins's murder, a $100,000 reward was offered to whoever could snare the group of criminals. The reward climbed to $500,000 before the group was apprehended.

On January 23, 2001, Colorado State Trooper Jason Lee Manspeaker died in an automobile accident on I-70 near Loveland Pass while investigating a reported sighting of the getaway vehicle of the Texas Seven. Trooper Manspeaker's Jeep Cherokee patrol vehicle hit a patch of ice and slammed into a flatbed trailer on the left shoulder of I-70.

Capture and conviction

The surviving members are held at the Allan B. Polunsky Unit

A friend of Wade Holder, the owner of the Coachlight Motel and R.V. Park in Woodland Park, Colorado, happened to watch the television program America's Most Wanted on January 20, 2001. He believed that the Texas 7, who were being compared to Ángel Maturino Reséndiz, were in Holder's trailer park and informed Holder so. When he confirmed this, he reported the suspicious activities to local authorities the next day on January 21.

The El Paso County Sheriff's Department SWAT team found Garcia, Rodriguez, and Rivas in a Jeep Cherokee in the RV Park. Authorities moved in and captured them at a nearby gas station. They then found Halprin and Harper in an RV; Halprin surrendered peacefully, but Harper was found dead after a standoff; he had shot himself in the chest with a pistol. The surviving four members were taken into police custody.[14]

On January 23, they received information on the whereabouts of the last two. They were hiding out in a Holiday Inn in Colorado Springs, Colorado. A deal brokered between the two, Newbury and Murphy, allowed them to make live TV appearances before they were arrested.[15] In the early hours of January 24, a local KKTV television anchorman, Eric Singer, was taken into the hotel where on camera he interviewed the two by telephone. Both of them harshly denounced the criminal justice system in Texas, with Newbury adding "the system is as corrupt as we are."

Huntsville Unit, where Rivas and Rodriguez died

In 2008 authorities indicted Patsy Gomez and Raul Rodriguez, the father of Michael Rodriguez, for conspiring to help the Texas 7.[16]

George Rivas was sentenced to death after being extradited to Texas. Subsequently, the other five surviving members of the Texas 7 were also sentenced to death along with Rivas.

Rodriguez announced that he wished to forgo any further appeal (beyond the appeal to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, mandatory in all death-penalty cases). He underwent a court-ordered psychiatric evaluation in January 2007, which concluded that he was mentally competent to decide to forgo further appeals, and he was executed on August 14, 2008, the first of the surviving members to be executed.[17][18] Rodriguez was TDCJ#999413, and his pre-death sentence TDCJ number was 698074.[19]

Rivas, TDCJ#999394, was executed on February 29, 2012, at 6:22 pm.[20]

As of March 2012 the remaining members are incarcerated on death row at the Polunsky Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ), located in West Livingston:[21]

Garcia has the TDCJ number 00999441,[22]

Halprin has the TDCJ number 00999453,[23]

Murphy has the TDCJ number 00999461,[24]

Newbury has the TDCJ number 00999403,[25]

Miscellaneous

In 2007, award-winning film and television production company Wild Dream Films produced The Hunt For The Texas 7, a 90-minute feature documentary about the prison break. The film was aired in late September 2008 on MSNBC. The film features interviews with members of The Texas 7 currently on Death Row, and eye witnesses. On March 25, 2011, Investigation Discovery aired an episode about the case subtitled "The Deadly Seven". They were also featured in an episode of 'Real Prison Breaks' on ITV4 in the UK.

Rivas had married a Canadian woman by proxy.[26]

References

This article includes a list of references, related reading or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (April 2009)

1.^ King, Gary C. "The Daring Escape of the Texas 7." Crime Library. 12. Retrieved on September 27, 2009.

2.^ King, Gary C. "The Daring Escape of the Texas 7." Crime Library. 13. Retrieved on September 27, 2009.

3.^ King, Gary C. "The Daring Escape of the Texas 7." Crime Library. 14. Retrieved on September 27, 2009.

4.^ King, Gary C. "The Daring Escape of the Texas 7." Crime Library. 10. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

5.^ "Offenders on Death row" Texas Department of Justice.[1] Retrieved June 15,2011.

6.^ King, Gary C. "The Daring Escape of the Texas 7." Crime Library. 11. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

7.^ King, Gary C. "The Daring Escape of the Texas 7." Crime Library. 16. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

8.^ King, Gary C. "The Daring Escape of the Texas 7." Crime Library. 15. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

9.^ King, Gary C."The Daring Escape of the Texas 7." Crime Library. 6. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

10.^ King, Gary C. "The Daring Escape of the Texas 7." Crime Library. 8. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

11.^ a b King, Gary C. "The Daring Escape of the Texas 7." Crime Library. 9. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

12.^ King, Gary C."The Daring Escape of the Texas 7." Crime Library. 17. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

13.^ King, Gary C."The Daring Escape of the Texas 7." Crime Library. 18. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

14.^ "FBI searching for 2 Texas escapees still on the loose". CNN. 2001-01-22. Archived from the original on February 9, 2006. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

15.^ "Captured convicts appear before judge; advised of rights and pending extradition". CNN. 2001-01-24. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

16.^ "Accomplice to Texas Seven prison escapees indicted in gun charges." Associated Press at The Dallas Morning News. May 24, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

17.^ "August 14 execution date for Texas 7 member". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. 2008-05-08. Archived from the original on May 8, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

18.^ "'Texas 7' Fugitive Who Dropped Appeals Executed." Associated Press at Fox News. Thursday August 14, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

19.^ "Rodriguez, Michael Anthony." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

20.^ "Leader of 'Texas 7' prison-break gang executed." Associated Press at Fox News. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

21.^ "West Livingston CDP, Texas." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on May 9, 2010.

22.^ "Garcia, Joseph (00999441)." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved on January 5, 2010. (Enter TDCJ ID 00999441)

23.^ "Halprin, Randy Ethan." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved on January 5, 2010. (Enter TDCJ ID 00999453)

24.^ "Murphy, Patrick Henry Jr." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved January 5, 2010. (Enter TDCJ ID 00999461)

25.^ "Newbury, Donald Keith." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved January 5, 2010. (Enter TDCJ ID 00999403)

26.^ Graczyk, Michael. "Leader of 'Texas 7' prison-break gang put to death." Houston Chronicle. Wednesday February 29, 2012. Retrieved on February 29, 2012.

George Rivas was one of the Texas Seven who escaped from the Connally Unit, a Texas prison near Karnes City, in December of 2000 and went on a crime spree which included the murder of police officer Aubrey Hawkins. At the time of the escape, Rivas was serving a life sentence for 13 counts of aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon, 4 counts of aggravated kidnapping and one count of burglary of a habitation.

On December 13, 2000, Rivas and six of his fellow inmates escaped from the Connally Prison Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. The group included Rivas, Joseph Garcia, Randy Halprin, Larry Harper, Patrick Murphy, Donald Newbury, and Michael Rodriguez. Eleven days after their escape, the [escapees] initiated a Christmas Eve robbery of the Oshman’s Superstore in Irving, Texas, that ended with the death of Irving police officer Aubrey Hawkins. Armed with weapons and two-way radios, Garcia, Halprin, Newbury, and Rodriguez entered the store just prior to closing pretending to be customers, while Rivas and Harper masqueraded as Oshman’s security guards. Murphy, the seventh member of the group, waited in a truck outside the store, serving as a lookout and checking police radio frequencies. Rivas and Harper explained to the store managers that they were investigating a theft at another Oshman’s and asked that a manager bring the store's employees together to look at a photo spread. Meanwhile, the other men moved throughout the store collecting merchandise. Once the employees were gathered together, Rivas brandished a gun and told everyone of his intent to rob the store. Rivas then instructed the men in his group to take the Oshman’s employees to the store’s breakroom and tie them up. While this was happening, Rivas told store manager Wesley Ferris to open the store's gun vault, safe, and cash registers. Rivas repeatedly warned Ferris not to try anything or he and the others would be shot. Afterwards, Rivas left Ferris with the employees in the breakroom, took Ferris’s car keys, exited the Oshman’s through the main front entrance, and drove Ferris’s Ford Explorer around the store to the loading dock located in the back. Altogether, the escapees stole over $70,000 in cash, forty-four firearms, ammunition, and other goods from the store, in addition to the employees’ jewelry and wallets.

During the robbery, Misty Wright, a girlfriend of one of the Oshman’s employees, waited in her car outside the store and saw the employees inside raising their hands over their heads. Wright called a friend who joined her in her car. The two saw Rivas exit the Oshman’s and drive Ferris’s Ford Explorer to the back of the store. Wright and her friend then fled the parking lot and called the police from a nearby restaurant. Rivas, who had seen Wright and her friend driving away in haste, used his two-way radio to warn the others, and he directed them to get to the back of the store. Within minutes, Murphy radioed the group, alerting them to a police vehicle he had seen entering the Oshman’s parking lot. The police dispatcher who took Wright’s emergency call sent four officers to the scene.

Irving police officer Aubrey Hawkins was the first to arrive. Hawkins drove directly through the parking lot to the back of the store, where he was shot eleven times by various members of the escapees. Evidence at trial established that at least five different guns fired at Hawkins from at least three directions in less than a minute and that he died immediately. Some of the escapees pulled Hawkins from the police vehicle and took his sidearm. Moments later, Rivas ran over Hawkins in the Ford Explorer, dragging his body approximately ten feet. According to Rivas, he did not know he had run over Hawkins until he heard the evidence at trial. During his trial, Rivas testified that as he approached Hawkins's vehicle, he thought he saw the officer reaching for his gun and that Rivas only shot Hawkins in an attempt to subdue him. Rivas claimed that he purposefully shot the officer in the chest because he knew Hawkins would be wearing a bulletproof vest. In addition, Rivas said that he shot at Hawkins four times in response to what he thought were shots fired by Hawkins. The evidence showed that Rivas was, in fact, shot during the period of intense gunfire.

Following the robbery, the seven inmates escaped to Colorado where someone identified them and notified the Federal Bureau of Investigation. All of the men were arrested, except Harper, who committed suicide before authorities could apprehend him. On the day of his arrest, Rivas was interviewed by police and, after waiving his Miranda rights, signed a 21-page written confession. During searches of an RV and another vehicle the escapees had been using, authorities recovered Hawkins’s gun, as well as guns and merchandise stolen from the Oshman’s in Irving, Texas.

Background: Following affirmance of defendant's conviction and death sentence for capital murder, and affirmance of denial of state post-conviction relief, petitioner sought federal habeas relief. The United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas denied relief. The District Court, 2010 WL 1223132, denied request for certificate of appealability (COA).

Holding: The Court of Appeals held that petitioner was not denied effective assistance of counsel.

Certificate of appealability denied.

PER CURIAM: (FN* Pursuant to 5th Cir. R. 47.5, the court has determined that this opinion should not be published and is not precedent except under the limited circumstances set forth in 5th Cir. R. 47.5.4.

Petitioner George Rivas, convicted of capital murder in Texas and sentenced to death, requests a Certificate of Appealability (COA) to appeal the district court's denial of his petition for a writ of habeas corpus. Because Rivas has not made a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right or otherwise met the qualifications for his application, his request for a COA is DENIED.

FN1. The following factual and procedural history is taken substantially verbatim from the magistrate judge's findings and recommendations. See Rivas v. Thaler, No. 3:06–CV–344–B, 2010 WL 1223130 (N.D.Tex. Jan.22, 2010).

On December 13, 2000, Rivas and six of his fellow inmates escaped from the Connally Prison Unit of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. The group, later known as the “Texas Seven,” included Rivas, Joseph Garcia, Randy Halprin, Larry Harper, Patrick Murphy, Donald Newbury, and Michael Rodriguez.

Eleven days after their escape, the Texas Seven initiated a Christmas Eve robbery of the Oshman's Superstore in Irving, Texas, that ended with the death of Irving police officer Aubrey Hawkins. Armed with weapons and two-way radios, Garcia, Halprin, Newbury, and Rodriguez entered the store just prior to closing pretending to be customers, while Rivas and Harper masqueraded as Oshman's security guards. Murphy, the seventh member of the group, waited in a truck outside the store, serving as a lookout and checking police radio frequencies. Rivas and Harper explained to the store managers that they were investigating a theft at another Oshman's and asked that a manager bring the store's employees together to look at a photo spread. Meanwhile, the other men moved throughout the store collecting merchandise. Once the employees were gathered together, Rivas brandished a gun and told everyone of his intent to rob the store. Rivas then instructed the men in his group to take the Oshman's employees to the store's breakroom and tie them up. While this was happening, Rivas told store manager Wesley Ferris to open the store's gun vault, safe, and cash registers. Rivas repeatedly warned Ferris not to try anything or he and the others would be shot. Afterwards, Rivas left Ferris with the employees in the breakroom, took Ferris's car keys, exited the Oshman's through the main front entrance, and drove Ferris's Ford Explorer around the store to the loading dock located in the back.

Altogether, the Texas Seven stole over $70,000 in cash, forty-four firearms, ammunition, and other goods from the store, in addition to the employees' jewellery and wallets.

During the robbery, Misty Wright, a girlfriend of one of the Oshman's employees, waited in her car outside the store and saw the employees inside raising their hands over their heads. Wright called a friend who joined her in her car. The two saw Rivas exit the Oshman's and drive Ferris's Ford Explorer to the back of the store. Wright and her friend then fled the parking lot and called the police from a nearby restaurant. Rivas, who had seen Wright and her friend driving away in haste, used his two-way radio to warn the others, and he directed them to get to the back of the store. Within minutes, Murphy radioed the group, alerting them to a police vehicle he had seen entering the Oshman's parking lot.

The police dispatcher who took Wright's emergency call sent four officers to the scene. Irving police officer Aubrey Hawkins was the first to arrive. Hawkins drove directly through the parking lot to the back of the store, where he was shot eleven times by various members of the Texas Seven. Evidence at trial established that at least five different guns fired at Hawkins from at least three directions in less than a minute and that he died immediately. Some of the escapees pulled Hawkins from the police vehicle and took his sidearm. Moments later, Rivas ran over Hawkins in the Ford Explorer, dragging his body approximately ten feet. According to Rivas, he did not know he had run over Hawkins until he heard the evidence at trial.

During his trial, Rivas testified that as he approached Hawkins's vehicle, he thought he saw the officer reaching for his gun and that he [Rivas] only shot Hawkins in an attempt to subdue him. Rivas claimed that he purposefully shot the officer in the chest because he knew Hawkins would be wearing a bulletproof vest. In addition, Rivas said that he shot at Hawkins four times in response to what he thought were shots fired by Hawkins. The evidence showed that Rivas was, in fact, shot during the period of intense gunfire.

Following the robbery, the Texas Seven escaped to Colorado where someone identified them and notified the Federal Bureau of Investigation. All of the men were arrested, except Harper, who committed suicide before authorities could apprehend him. On the day of his arrest, Rivas was interviewed by police and, after waiving his Miranda rights, signed a 21–page written confession. During searches of an RV and another vehicle the Texas Seven had been using, authorities recovered Hawkins's gun, as well as guns and merchandise stolen from the Oshman's in Irving, Texas.

Following the close of the evidence at trial, a Dallas County jury convicted Rivas of capital murder. See Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 19.03.

The evidence presented during the punishment phase of Rivas's trial established the following: Rivas was serving seventeen life sentences, some concurrent, when he escaped from prison. Rivas had prior convictions for aggravated kidnapping, burglary, and aggravated robbery of an Oshman's in El Paso, Texas. Evidence from both the State and the defense showed that Rivas was the ringleader of the Texas Seven, and that he had planned their escape from the Connally Unit, as well as the robbery of the Oshman's in Irving. The State introduced evidence showing that Rivas and the other escapees assaulted and threatened prison employees during their escape. And, after the escape, Rivas planned and led three other robberies before eventually targeting the Oshman's in Irving. In addition, the State elicited testimony from Rivas's half-sister, who claimed that Rivas had sexually abused her from the age of six through sixteen. Finally, the State presented expert testimony from a criminal forensic psychiatrist who testified that based on his review of Rivas's history, it was his opinion that Rivas would probably commit criminal acts of violence in the future and continue to threaten society.

Rivas testified during sentencing and admitted to committing numerous crimes, as well as to planning the group's escape from prison and the robbery of the Oshman's in Irving. In his defense, Rivas told the jury that he tried to be polite and minimize the pain he inflicted on others during his crimes. Rivas also said that he did not intend to kill officer Hawkins, nor that he had planned to commit additional robberies. Rivas denied his half-sister's allegations of abuse. Ultimately, Rivas told the jury that he would rather die than be sent back to prison.

After the jury answered the special issues set forth in Tex.Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 37.071, the state trial court set Rivas's punishment at death by lethal injection.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Rivas's conviction and sentence on direct appeal, Rivas v. State, No. 74,143 (Tex.Crim.App. June 23, 2004) (unpublished), and the Supreme Court denied certiorari, Rivas v. Texas, 543 U.S. 1166, 125 S.Ct. 1342, 161 L.Ed.2d 142 (2005). Rivas also filed a state petition for habeas corpus while his direct appeal was pending. The state trial court held an evidentiary hearing, entered findings of fact and conclusions of law, and recommended that the petition be denied. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals adopted the trial court's findings and denied relief. Ex parte Rivas, No. WR–63286–01, 2006 WL 367474 (Tex.Crim.App. Feb.15, 2006) (per curiam).

Rivas next filed a federal habeas petition in the Northern District of Texas, alleging nine grounds for relief. In addition, Rivas filed a separate brief—over eleven months after filing his original habeas petition and without leave of court—in which he argued that 28 U.S.C. § 2254 violates the Separation of Powers doctrine. The matter was initially referred to a magistrate judge who entered detailed findings and conclusions, and recommended denying relief on all grounds, including Rivas's Separation of Powers claim. Rivas v. Thaler, No. 3:06–CV–344–B, 2010 WL 1223130 (N.D.Tex. Jan.22, 2010). The district court adopted the magistrate's findings and recommendations, with minor corrections, and denied a COA on all claims. Rivas v. Thaler, No. 3:06–CV–344–B, 2010 WL 1223132 (N.D.Tex. Mar.29, 2010). Rivas now requests a COA from this court on the nine issues raised below, as well as on his Separation of Powers claim.

II

Because Rivas filed his federal habeas petition after the effective date of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA), his petition is governed by the procedures and standards provided therein. See Parr v. Quarterman, 472 F.3d 245, 251–52 (5th Cir.2006). Under AEDPA, a petitioner must obtain a COA before appealing the district court's denial of habeas relief. See 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c). This is a jurisdictional prerequisite. See Miller–El v. Cockrell, 537 U.S. 322, 336, 123 S.Ct. 1029, 154 L.Ed.2d 931 (2003) (“[U]ntil a COA has been issued federal courts of appeals lack jurisdiction to rule on the merits of appeals from habeas petitioners.”).

A COA will be granted only if the petitioner makes “a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right.” 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c)(2). “A petitioner satisfies this standard by demonstrating that jurists of reason could disagree with the district court's resolution of his constitutional claims or that jurists could conclude the issues presented are adequate to deserve encouragement to proceed further.” Miller–El, 537 U.S. at 327, 123 S.Ct. 1029 (citation omitted). “The question is the debatability of the underlying constitutional claim, not the resolution of that debate.” Id. at 342, 123 S.Ct. 1029. “Indeed, a claim can be debatable even though every jurist of reason might agree, after the COA has been granted and the case has received full consideration, that petitioner will not prevail.” Id. at 338, 123 S.Ct. 1029. “While the nature of a capital case is not of itself sufficient to warrant the issuance of a COA, in a death penalty case any doubts as to whether a COA should issue must be resolved in the petitioner's favor.” Johnson v. Quarterman, 483 F.3d 278, 285 (5th Cir.2007) (citing Ramirez v. Dretke, 398 F.3d 691, 694 (5th Cir.2005)).

We also recognize that the district court evaluated Rivas's claims under AEDPA's deferential framework. Under AEDPA, a federal court cannot grant habeas relief on any claim adjudicated on the merits by a state court unless the state court's adjudication “resulted in a decision that was contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court,” or “resulted in a decision that was based on an unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the evidence presented in the State court proceeding.” Cullen v. Pinholster, ––– U.S. ––––, 131 S.Ct. 1388, 1398, 179 L.Ed.2d 557 (2011) (quoting 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(1) and (2)). A state court's decision is deemed contrary to clearly established federal law if it reaches a legal conclusion in direct conflict with a prior decision of the Supreme Court or if it reaches a different conclusion than the Supreme Court based on materially indistinguishable facts. See Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362, 404–08, 120 S.Ct. 1495, 146 L.Ed.2d 389 (2000). A state court's decision constitutes an unreasonable application of clearly established federal law if it is “objectively unreasonable.” Id. at 409, 120 S.Ct. 1495; see also Schriro v. Landrigan, 550 U.S. 465, 473, 127 S.Ct. 1933, 167 L.Ed.2d 836 (2007) (“The question under AEDPA is not whether a federal court believes the state court's determination was incorrect but whether that determination was unreasonable—a substantially higher threshold.”). In addition, under § 2254(e)(1), the state court's findings of fact are presumed to be correct unless rebutted by clear and convincing evidence. Id. at 473–74; see also Wood v. Allen, ––– U.S. ––––, 130 S.Ct. 841, 847, 175 L.Ed.2d 738 (2010).

III

Rivas requests a COA on ten issues: (1) whether trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance by failing to object to an improper closing argument by the prosecutor; (2) whether trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance by failing to make a “fair cross-section” objection to the jury pool; (3) whether trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance by failing to object to the prosecutor's use of out-of-court statements by Rivas's co-defendants at the punishment phase of trial; (4) whether the trial court erroneously admitted expert testimony on sentencing regarding future dangerousness; (5) whether Texas's lethal injection protocol violates the Eighth Amendment; (6) whether Rivas's due process rights were violated by the trial court's failure to instruct the jury on the burden of proof regarding the mitigating factors contained in the jury charge; (7) whether the trial court's jury instructions used terms that were unconstitutionally vague and undefined; (8) whether Texas's death penalty statute, which does not require that the jury be instructed on the consequences of its failure to agree on a punishment phase special issue, is unconstitutional; (9) whether the trial court erred in instructing the jury in sentencing that it was not to consider how long Rivas might serve in prison if sentenced to life; and (10) whether 28 U.S.C. § 2254 violates the Separation of Powers doctrine. Of the ten issues presented, Rivas acknowledges that five are expressly foreclosed by either Supreme Court or this court's precedents, or both. We address each issue in turn.

A

Rivas first claims that his trial counsel rendered constitutionally ineffective assistance at trial when he failed to object to the prosecutor's closing argument.

We evaluate this claim, and the two ineffective assistance claims that follow, under the familiar standard set out in Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 104 S.Ct. 2052, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984). To prevail, Rivas must show by a preponderance of the evidence that his attorney's performance was deficient and that the deficient performance prejudiced his defense. Id. at 687, 104 S.Ct. 2052. In assessing trial counsel's performance, we give deference to the strategic decisions made by counsel, applying the strong presumption that counsel's performance “falls within the wide range of reasonable professional assistance.” Id. at 689, 104 S.Ct. 2052. In doing so, we evaluate trial counsel's conduct from counsel's perspective at the time of trial, endeavoring to “eliminate the distorting effects of hindsight.” Id. To show prejudice, Rivas must show that “there is a reasonable probability that, but for counsel's unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been different.” Id. at 694, 104 S.Ct. 2052. “Reasonable probability” is defined as a probability sufficient to undermine confidence in the outcome. Id. Ultimately, Strickland's prejudice inquiry focuses on whether counsel's deficient performance “renders the result of the trial unreliable or the proceeding fundamentally unfair.” Williams, 529 U.S. at 393 n. 17, 120 S.Ct. 1495. And unless Rivas makes both showings under Strickland—deficient performance and prejudice—it cannot be said that his conviction or death sentence “resulted from a breakdown in the adversary process that renders the result unreliable” and requires reversal. Strickland, 466 U.S. at 687, 104 S.Ct. 2052.

Rivas claims that the prosecutor's summation was improper because the prosecutor did not discuss the specific intent required of Rivas's co-conspirators in causing Hawkins's death. Rivas contends that this omission was contrary to the law contained in the jury instructions and “invited the jury to engage in jury nullification.” Pet. Br. at 8. Rivas takes issue with the following portion of the prosecutor's argument, specifically, those parts in bold:

The evidence in this case is overwhelming. It is a case which you—it has been explained to you that the State can prove one of two ways, or both, and I submit to you that we have done both. We can prove to you that [Rivas] intentionally killed Aubrey Hawkins because he was a police officer and he knew that. We can prove to you that he killed Aubrey Hawkins because he murdered him in the course of a robbery. Or we can prove to you that he entered into this conspiracy, and even if he didn't have the intent—let's just take for a moment that ludicrous explanation in his confession that he didn't have the intent to kill anyone out there. If you agree with that, he is still guilty under the law because he entered into a conspiracy to commit robbery and he should have anticipated that someone would die. And this is a plan destined to fail, folks.

According to Rivas, the State did not establish beyond a reasonable doubt that either Rivas or any of his co-conspirators shot at Hawkins with the specific intent to cause his death. The State erred, Rivas contends, in failing to explain the specific intent requirement to the jury, and Rivas's counsel was therefore ineffective for failing to object to the prosecutor's argument containing the alleged omission.

The trial court correctly instructed the jury that the State could prove Rivas's guilt by proving either: (1) that Rivas murdered Hawkins with knowledge that Hawkins was a police officer, or (2) that Rivas entered into a conspiracy to commit robbery and that one of Rivas's co-conspirators intentionally and knowingly killed Hawkins in furtherance of that conspiracy. See Tex. Penal Code Ann. §§ 7.02(b), 19.03. In addition, a second prosecutor explained to the jury that the co-conspirator who actually killed Hawkins had to have acted intentionally and knowingly.

The crux of Rivas's claim is that the prosecutor misstated the law in his closing argument to the jury, and that his trial counsel was ineffective for failing to object. The state habeas court rejected this claim, finding that the prosecutor did not misstate Texas law governing the culpability of party conspirators. The court found that Rivas had misinterpreted the prosecutor's argument, and that the argument was not improper because the prosecutor was “simply focusing on [Rivas's] mental state” at the time. FN2 The court found in addition that Rivas's trial counsel was making a strategic decision in not objecting to the prosecutor's argument and noted that trial counsel's informed strategic decisions rarely constitute grounds for an ineffective assistance of counsel claim. The court concluded that Rivas's trial counsel was not deficient for failing to proffer what would have been a meritless objection. See Turner v. Quarterman, 481 F.3d 292, 298 (5th Cir.2007); Green v. Johnson, 160 F.3d 1029, 1037 (5th Cir.1998) (“[F]ailure to make a frivolous objection does not cause counsel's performance to fall below an objective level of reasonableness.”).

FN2. The state habeas court found, in pertinent part, that:

252. ... the prosecutor did not discuss what mental state the co-conspirator who actually killed Officer Hawkins had to possess, but this admission [sic] did not render his argument improper. The Court finds that at this point in the argument, the prosecutor was simply focusing on [Rivas's] mental state, rather than his co-conspirators; thus, the omission was not noteworthy.

253. Moreover, the Court finds that the argument's silence on the matter of the killing co-conspirator's mental state does not, in itself, convey the message that proof of an intentional or knowing killing was not a prerequisite to [Rivas's] conviction for capital murder. And, the Court finds that such an inference would be illogical.

The state habeas court alternatively addressed prejudice under Strickland's second prong, and found that Rivas's claim failed in that regard as well. It is well settled that jurors are presumed to follow the trial court's instructions. See, e.g., Galvan v. Cockrell, 293 F.3d 760, 765 (5th Cir.2002). In light of the trial court's correct instructions to the jury, see Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 7.02(b), the state habeas court found that Rivas had failed to “rebut the presumption that counsel's decision not to object was a sound one, much less demonstrate how he was prejudiced by it.”

Rivas has not demonstrated that an objection to the prosecutor's closing argument would have been meritorious had it been made. As such, Rivas's trial counsel cannot have rendered ineffective assistance by failing to object. Because this claim fails under Strickland's first prong, we need not consider prejudice under Strickland's second prong. Rivas has not made a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right. We deny his request for a COA on this issue accordingly.

B

Next, Rivas contends that his trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance by failing to make a “fair cross-section” objection to the jury pool. Specifically, Rivas claims that Dallas County's method of convening jury panels results in a systematic exclusion of Hispanics and young adults (i.e., persons 18–34 years old), and that counsel failed to protect Rivas's Sixth and Fourteenth Amendment rights to have a fair cross-section of the community on the panel from which his jury was chosen. We must first determine whether Rivas's fair cross-section claim has merit, since it would not be deficient for counsel to withhold a meritless objection. See Turner, 481 F.3d at 298; Green, 160 F.3d at 1037.

To establish a prima facie fair cross-section claim, Rivas must make three showings. First, he must demonstrate “that the group alleged to be excluded is a ‘distinctive’ group in the community.” Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357, 364, 99 S.Ct. 664, 58 L.Ed.2d 579 (1979). Second, he must establish “that the representation of this group in venires from which juries are selected is not fair and reasonable in relation to the number of such persons in the community.” Id. Finally, he must show “that this underrepresentation is due to systematic exclusion of the group in the jury-selection process.” Id. If Rivas fails to demonstrate any of these elements, he has failed to show a constitutional violation. See Timmel v. Phillips, 799 F.2d 1083, 1086 (5th Cir.1986).

The state habeas court found that although Hispanics qualify as a distinctive group in Dallas County, persons 18 to 34—or persons of any particular age group—do not qualify as a “distinctive group” for Duren purposes.FN3 The district court set this issue aside, finding that Rivas's claim relating to both groups failed under Duren's third prong. We begin our analysis there.

FN3. In reaching this conclusion, the state habeas court relied on Weaver v. State, 823 S.W.2d 371, 373 (Tex.App.-Dallas 1992). We note that several federal circuit courts have also considered this issue and found that persons between the ages of 18 and 34 do not constitute a recognizable, distinct class under Duren. See, e.g., Johnson v. McCaughtry, 92 F.3d 585, 590–93 (7th Cir.1996); Wysinger v. Davis, 886 F.2d 295, 296 (11th Cir.1989); Ford v. Seabold, 841 F.2d 677, 681–82 (6th Cir.1988); Barber v. Ponte, 772 F.2d 982, 996–1000 (1st Cir.1985); United States v. Kuhn, 441 F.2d 179, 181 (5th Cir.1971). Because we find that Rivas's claim fails under Duren's third prong (i.e., the “systematic exclusion” requirement), we need not address whether persons 18–34 constitute a “distinct group” under Duren's first prong.

The state habeas court analyzed Duren's “systematic exclusion” requirement and found that Rivas failed to show an underrepresentation of either Hispanics or persons 18 to 34 that was inherent in Dallas County's jury selection process. See Duren, 439 U.S. at 366, 99 S.Ct. 664. As the state habeas court and the district court correctly observed, Rivas has not alleged any underrepresentation in the percentage of individuals in these groups who were called for jury service. Rather, the crux of Rivas's claim is that the percentage of individuals in these two groups who actually appeared for jury service was significantly less than the percentage of such individuals in Dallas County at the time. Rivas contends that low juror pay and Dallas County's lack of enforcement of its summonses is to blame for the disparate turnout. But the fact that certain groups of persons called for jury service appear in numbers unequal to their proportionate representation in the community does not support Rivas's allegation that Dallas County systematically excludes them in its jury selection process. Such an occurrence does not constitute the type of affirmative barrier to selection for jury service that is the hallmark of a Sixth Amendment violation. See Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522, 531, 95 S.Ct. 692, 42 L.Ed.2d 690 (1975) (holding unconstitutional a state statute that excluded women from jury service unless they had previously filed written declaration indicating their desire to serve).