Executed January 8, 2014 06:45 p.m. EST by Lethal Injection in Florida

1st murderer executed in U.S. in 2014

1360th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Florida in 2014

82nd murderer executed in Florida since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(1) |

|

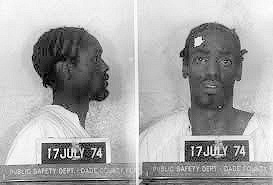

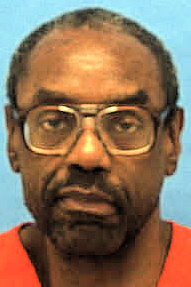

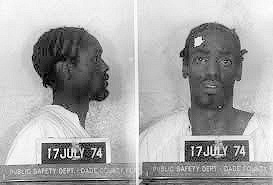

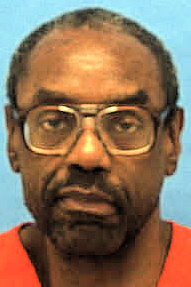

Thomas Knight a/k/a Askari Abdullah Muhammad B / M / 23, 29 - 62 |

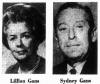

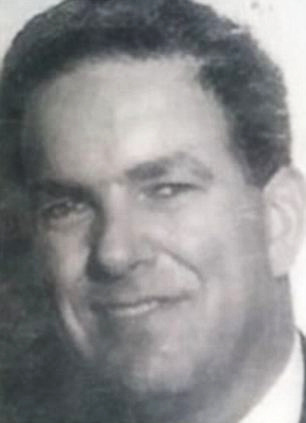

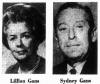

Sydney Gans W / M / 64 Lillian Gans W / F / 60 Richard James Burke OFFICER W / M / 48 |

07-17-74 10-12-80 |

.30 Rifle Stabbing with Sharp Spoon |

Employer's Wife Prison Guard |

03-12-96 04-21-75 03-12-96 01-20-83 |

While awaiting trial, he and 10 other Florida inmates escaped from jail in 1974, leading to a nationwide manhunt including a top 10 fugitives listing by the FBI. During the escape, Knight was in the armed robbery of a liquor store in Cordele, Georgia where two clerks were shot, one fatally. He was never tried in that case.

Back on death row in Florida, in 1980 Knight became angry that he had to shave his beard before seeing a visitor and used a sharpened spoon to stab to death prison guard Richard Burke.

Citations:

Knight v. State, 338 So.2d 201 (Fla. 1976). (Direct Appeal-Gans)

Knight v. State, 394 So.2d 997 (Fla. 1981). (PCR-Gans)

Muhammad v. State, 494 So.2d 969 (Fla. 1986). (Direct Appeal-Burke)

Knight v. State, 746 So.2d 423 (Fla. 1998). (Direct Appeal-Gans-After Resentencing)

Muhammad v. Secretary, Florida Dept. of Corrections, 733 F.3d 1065 (11th Cir. 2013). (Habeas-Gans-Reversing Granting of Writ)

Final / Special Meal:

1½ slices of sweet potato pie, one piece of coconut cake, half a loaf of banana nut bread, a quarter bottle of Sprite, two tablespoons of strawberries, butter-pecan ice cream, a small container of vanilla ice cream and a handful of Fritos corn chips.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

Florida Department of Corrections

DC Number: 017434Current Prison Sentence History:

07/17/1974 1ST DG MUR/PREMED. OR ATT. 04/21/1975 MIAMI-DADE 7405978 DEATH SENTENCE

07/17/1974 1ST DG MUR/PREMED. OR ATT. 04/21/1975 MIAMI-DADE 7405978 DEATH SENTENCE

10/12/1980 1ST DG MUR/PREMED. OR ATT. 01/20/1983 BRADFORD 8000341 DEATH SENTENCE

Incarceration History: 04/23/1975 to 01/07/2014

Detainers: 05/19/1982 SO BRADFORD CO FL. DETAIN 02/02/1983

"Thomas Knight, who killed Miami couple and a prison guard, executed," by David Ovalle (01.07.14)

STARKE -- Over a staggering four decades in Florida’s criminal justice system, Thomas Knight repeatedly staved off execution for the brutal 1974 murders of a Bay Harbor Islands couple — breaking out of jail, murdering a prison guard and disrupting court hearings with angry outbursts. But when all the appeals had finally run out Tuesday evening, Knight exited the world without an apology to the families of his victims or any statement at all. “No,” is all Knight muttered when a corrections official asked if he had any last words. “He absolutely went out like a lamb, nothing like how he was in the courtroom,” said retired Miami-Dade homicide detective Greg Smith, who attended the execution with Miami-Dade prosecutor Gail Levine. “In the end, today was some measure of justice for the families.”

At 6:31 p.m. Tuesday at the Florida State Prison, his home for most of the past 40 years, Knight was injected with a lethal cocktail of drugs. The execution warrant was technically issued for the fatal stabbing of corrections officer Richard Burke in 1980. But he also had been sentenced to death for the brutal slayings of Sydney and Lillian Gans, who he had kidnapped and shot to death in the woods of South Miami-Dade six years earlier . Knight’s blinking eyes snapped shut. Covered in a sheet, his hands wrapped in gauze, his arms pierced by IV’s, Knight seemed to drift into slumber. His breathing slowed. A prison official tapped his eyelids and slightly shook his shoulders. At 6:45 p.m., a doctor pronounced the triple murderer — who had spent more time on death row than all but two other killers — dead.

Behind a glass pane, Burke’s daughters, who were raised near this same prison, watched in tears. So did two former co-workers of the slain officer. “It’s hard to say this is where my dad took his last breath,” Carolyn Burke Thompson, 47, of Tennessee, told reporters afterward. “But I’m at peace now.” Said Burke’s other daughter, Margaret Dela Vega: “My daddy can finally rest in peace.”

The execution caps Knight’s 40-year slog through the criminal justice system, which led one federal court to blast the “gridlock and inefficiency of death penalty litigation.” Even on Tuesday, the possibility of another delay hung over the final minutes – the execution was pushed back about a half-an-hour as the U.S. Supreme Court mulled, but denied, a final attempt at a stay. “It doesn’t bring my grandparents back … but it’s over. At least, in some sense, it allows us for move forward,” said Judd Shapiro, the grandson of the Ganses. Shapiro and his mother declined to attend an execution they believed would be too draining emotionally. “I’d like to hope, in some fashion, this helps other people, that they realize that sooner or later the right thing does happen,’’ he said. “But it shouldn’t take this long. It shouldn’t take 40 years.”

At rifle-point, Knight kidnapped Sydney Gans, a prominent businessman, and his wife in July 1974, forcing them to withdraw $50,000 from a downtown Miami bank. Gans was able to alert police, who covertly tailed their car as Knight forced them to drive south. But in a remote wooded area, Knight shot each of his hostages with a bullet to the neck before he was captured. He was found hiding in the woods, caked in mud, with the murder weapon and money.

While awaiting trial, Knight escaped from the Dade County jail. Police say he killed a shopkeeper in Georgia before his re-capture 101 days later. Knight was convicted of the Ganses’ murders in 1975 and sent to Death Row. It was there that Knight fatally stabbed Burke in the chest. He was later convicted and sent back to Death Row for the crime.

Years of appeals followed and his death sentence in the Gans case was reversed in 1986. One decade later, Knight was again sentenced to death for the Miami-Dade case. A federal judge again reversed his death sentence in the Gans case, only to have it reinstated by a federal appeals court in September. A December execution was again delayed by a month after Knight alleged that a new drug used in the lethal injection process amounted to cruel and unusual punishment. The state’s high court did not agree.

On Tuesday, the beard Knight grew for the 1996 re-sentencing was gone. So were his outbursts. His final meal, unlike his life, was mostly sweet: portions of sweet potato pie, coconut cake, banana nut bread, vanilla ice cream, strawberry-and-butter pecan ice cream and Fritos corn chips — all washed down by a quarter of a bottle of Sprite.

Knight’s dark history

July 17, 1974 – Thomas Knight kidnaps and murders Sydney and Lillian Gans of Bay Harbor Islands. He is immediately arrested.

September 1974 – Knight and 10 other inmates escape from Dade County jail. He is placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List.

October 1974 – Police believe Knight and another man fatally shoot a liquor store clerk during a robbery for $641 in Crisp County, GA. He is not charged.

December 1974 – FBI agents capture Knight in New Smyrna Beach. He is found with a shotgun and two pistols, all stolen.

April 1976 – A Miami-Dade jury convicts Knight of murdering the couple. He is sentenced to death.

October 1980 – Using a sharpened spoon, Knight stabs and kills corrections Officer Richard Burke at the Florida State Prison in Starke.

March 1981 – Knight is scheduled to be executed after Gov. Lawton Chiles signs his death warrant. A federal judge stays his execution pending more appeals.

January 1983 – Knight is convicted and sentenced to death for the Burke murder.

January 1996 – A federal appeals court overturns his death sentence in the Gans case, ordering a new penalty phase trial.

February 1996 – After a new sentencing phase, Knight is again sentenced to death. He is repeatedly banned from the courtroom because of his disruptive behavior.

March 2006 – With state courts repeatedly affirming his conviction and sentence, Knight’s lawyers appeal to a Miami federal judge.

November 2012 – Six years after the appeal was first filed, Miami U.S. Judge Adalberto Jordan reverses Knight’s death sentence. He orders a new sentencing hearing or life sentences for the convict.

September 2013 – A federal appeals court reverses Judge Jordan, reinstating the death penalty for Knight. “To learn about the gridlock and inefficiency of death penalty litigation, look no further than this appeal,” the court writes.

October 2013 – Gov. Rick Scott signs death warrant for Knight, not for the Miami-Dade murders but for the slaying of Burke. The execution is scheduled for Dec. 3.

November 2013 – The Florida Supreme Court delays the execution, ordering a Bradford judge to hold a hearing to consider whether a new drug used in the lethal injection procedure constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.

December 2013 – The state’s high court lifts the stay of execution after ruling Knight has failed to prove the drug is unsafe. Gov. Rick Scott re-schedules the execution for Jan. 7.

"Florida executes Askari Abdullah Muhammad (Thomas Knight) for killing guard, couple," by Tamara Lush. (Jan 8, 2014 - 7:06am)

STARKE | A Florida inmate was executed Tuesday for fatally stabbing a prison guard with a sharpened spoon while on death row for abducting and killing a Miami couple. Askari Abdullah Muhammad, previously known as Thomas Knight, was pronounced dead at 6:45 p.m. Tuesday after a lethal injection at Florida State Prison, the governor's office said. The execution took place in the same prison where Muhammad killed corrections officer Richard Burke in 1980.

"This is where my dad took his last breath," said the slain guard's daughter, 47-year-old Carolyn Burke Thompson. She was among several family members who witnessed the execution and could be seen crying in the front row as it was carried out. "The system finally has worked. I am at peace knowing I don't have to wait any longer. I miss my dad a lot," she said.

Muhammad, 62, was initially condemned to die for the 1974 abduction and killings of Sydney and Lillian Gans of Miami. Tuesday's execution was specifically for Burke's killing.

Muhammad was visited by his four sisters Monday and earlier Tuesday by a friend. He declined to make any statement before the sentence was carried out. A small group opposed to the death penalty protested outside the prison. His execution was delayed for so long by numerous appeals and rulings, including a 1987 federal appeals court tossing out his original death sentence because he hadn't been allowed to put character and background witnesses on the stand during the penalty phase. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear his final appeals, but Justice Stephen Breyer said in a dissent he would have granted a stay to hear Muhammad's claims that it may be unconstitutional to execute an inmate after such a long time on death row.

Court documents show that Muhammad fatally stabbed Burke as he was being escorted to the prison shower. The inmate had become upset, the documents say, because he was told he couldn't see a visitor unless he shaved his full beard. The documents added he had been overheard by guards to remark that "it looks like I'll have to start sticking people."

In the earlier slayings, Muhammad had worked for Gans at a paper bag company before abducting him in the business parking lot with a rifle. He ordered Gans to drive home, pick up his wife and then head to a bank to withdraw $50,000. Inside the bank, Gans asked a manager to alert authorities. Both the FBI and police were able to follow the car for a while, including use of aircraft, but lost track of it for a short time in a rural area of Miami-Dade County. Trial testimony showed that's when Muhammad shot the couple and tried to hide by burying himself, the rifle and the money in mud and weeds.

Muhammad was found soon after and arrested. While awaiting trial, he and 10 other inmates escaped from jail, leading to a nationwide manhunt including a top 10 fugitives listing by the FBI. Authorities say Muhammad was involved after his escape in the fatal October 1974 shooting of a liquor store clerk during an armed robbery in Cordele, Ga., that wounded a second clerk. He was never tried in that case. The FBI finally arrested Muhammad on New Year's Eve in 1974 in Florida.

Muhammad converted to Islam in prison, changing his name from Knight. During his 1996 resentencing, he cursed at the judge and lawyers and yelled "Allahu Akbar!" — "God is great" in Arabic.( Associated Press writer Curt Anderson in Miami contributed to this story.)

"Florida man on death row for 40 years executed; killed couple, prison guard." (Jan 7, 2014 7:24pm)

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. (Reuters) - A Florida man who spent nearly 40 years on death row for killing a Miami couple and later stabbing a prison guard was executed on Tuesday, a state prison official said. Askari Abdullah Muhammad, 62, who was known as Thomas Knight when he killed his former employer and his wife in 1974, was pronounced dead at 6:45 p.m. EDT (2345 GMT) from a lethal injection, said Misty Cash, a spokeswoman for the Florida Department of Corrections. (Reporting by Kevin Gray; Editing by Bernard Orr)

"State executes man who killed couple, guard," by Monivette Cordeiro. (January 7, 2014 at 10:47 pm)

RAIFORD — A Florida inmate who abducted and killed a Miami couple in 1974 and later stabbed a prison guard to death at the Florida State Prison in 1980 was executed by lethal injection Tuesday night.

Corrections officer Richard Burke's relatives watched from behind a glass window at the Florida State Prison as 62-year-old Askari Abdullah Muhammad, previously known as Thomas Knight, was executed in the killing of Burke. None of the relatives of Miami couple Sydney and Lillian Gans attended the execution.

At 6:30 p.m., the brown curtain behind the glass door was lifted and Muhammad was asked if he had any last words, to which he replied, “No.” He blinked a few times and then shut his eyes as the lethal injection began coursing through his veins at 6:31 p.m. Burke's daughter Carolyn Burke Thompson wiped tears from her face as the man who killed her father was being executed. Thompson's fiance, Harold Spencer, held her arm and hugged her as they watched Muhammad's final moments. During the final moments of the execution, Muhammad's right eye opened slightly. Fourteen minutes later, he was declared dead by a doctor at 6:45 p.m. after having been on death row for almost four decades.

A personal friend had visited Muhammad earlier Tuesday, and four of his sisters had visited him on Monday, said Florida Department of Corrections spokeswoman Jessica Cary. None of his relatives was present when he was executed, she said. Muhammad's final meal consisted mostly of desserts, including 1½ slices of sweet potato pie, one piece of coconut cake, half a loaf of banana nut bread, a quarter bottle of Sprite, two tablespoons of strawberries, butter-pecan ice cream, a small container of vanilla ice cream and a handful of Fritos corn chips. He appeared to be calm in his final hours, Cary said.

Muhammad was first condemned to die for the abduction and shooting of the Ganses in 1974. He was given the death penalty again for killing Burke, the corrections officer, in 1980 with a sharpened spoon. Sydney Gans, 64, had just given Muhammad, then 23, a job at his paper bag company 10 days before Gans was kidnapped at gunpoint. Muhammad forced Gans to drive to the couple's home, where Muhammad then abducted Gans' wife, Lillian. The three then drove to the couple's bank, where Muhammad forced Gans to walk inside and withdraw $50,000. Inside, Gans was able to ask a bank manager to call the authorities.

Although local officials and the FBI were able to follow Muhammad as he drove away with the couple, they lost track of the car in a rural area of Miami-Dade County. Authorities say that's when Muhammad shot Sydney and Lillian Gans in the head and tried to hide by burying himself, the gun and the money in the mud and weeds, but he was found by authorities.

While waiting for his trial, Knight and 10 other inmates escaped from jail, and although he was not charged, authorities said during this time he was involved in the 1974 shooting of a liquor store clerk during an armed robbery in Georgia. He was finally arrested a few months later by the FBI in Florida. Muhammad was convicted by a jury in 1975 and a judge sentenced him to death.

In 1980, in the same prison at which he was executed on Tuesday, Muhammad stabbed a sharpened spoon into the chest of the 48-year-old Burke after he became upset that officials told him he couldn't see a visitor.

Muhammad's execution on Tuesday had been delayed by numerous appeals and rulings. One ruling in 1987 from a federal appeals court set aside his original death sentence because during the penalty phase he had not been allowed to put character and background witnesses on the stand. Muhammad's execution was originally scheduled for Dec. 3 but was stayed several weeks before by the Florida Supreme Court after he filed an appeal claiming that one of the drugs used in the process, midazolam hydrochloride, may not prevent pain.

On Dec. 19, the Florida Supreme Court denied the claim, supporting the district court in Bradford County, which had ruled that there was no evidence that the drug causes “serious illness and needless suffering.” The drug, which has already been used in the previous executions of William Happ and Darius Kimbrough, is a sedative injected before two other drugs induce paralysis and then cardiac arrest. Muhammad claimed midazolam hydrochloride violated a constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Gov. Rick Scott signed the death warrant after the Florida Supreme Court rejected Muhammad's challenge in December to new chemicals used in the state's execution procedure.

For Thompson, it has been a long 33 years since her father's murder. “It's been a long time coming,” she said. “The system has finally worked. My dad would not have died if the system had worked the first time.” Thompson had traveled to the prison from Tennessee to witness the execution. Her sister Meg Dela Vega and brother-in law Glenn Dela Vega also were present. “Those families deserve the peace that I feel right now,” Thompson said. “Thank God it's over.”

"Florida executes man who killed guard, couple." (AP Updated: January 8, 2014 at 12:58 AM)

STARKE, Fla. (AP) — A Florida inmate was executed Tuesday for fatally stabbing a prison guard with a sharpened spoon while on death row for abducting and killing a Miami couple. Askari Abdullah Muhammad, previously known as Thomas Knight, was pronounced dead at 6:45 p.m. Tuesday after a lethal injection at Florida State Prison, the governor's office said. The execution took place in the same prison where Muhammad killed corrections officer Richard Burke in 1980.

"This is where my dad took his last breath," said the slain guard's daughter, 47-year-old Carolyn Burke Thompson. She was among several family members who witnessed the execution and could be seen crying in the front row as it was carried out. "The system finally has worked. I am at peace knowing I don't have to wait any longer. I miss my dad a lot," she said.

Muhammad, 62, was initially condemned to die for the 1974 abduction and killings of Sydney and Lillian Gans of Miami. Tuesday's execution was specifically for Burke's killing. Muhammad was visited by his four sisters Monday and earlier Tuesday by a friend. He declined to make any statement before the sentence was carried out. A small group opposed to the death penalty protested outside the prison.

His execution was delayed for so long by numerous appeals and rulings, including a 1987 federal appeals court tossing out his original death sentence because he hadn't been allowed to put character and background witnesses on the stand during the penalty phase. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear his final appeals, but Justice Stephen Breyer said in a dissent he would have granted a stay to hear Muhammad's claims that it may be unconstitutional to execute an inmate after such a long time on death row.

Court documents show that Muhammad fatally stabbed Burke as he was being escorted to the prison shower. The inmate had become upset, the documents say, because he was told he couldn't see a visitor unless he shaved his full beard. The documents added he had been overheard by guards to remark that "it looks like I'll have to start sticking people."

In the earlier slayings, Muhammad had worked for Gans at a paper bag company before abducting him in the business parking lot with a rifle. He ordered Gans to drive home, pick up his wife and then head to a bank to withdraw $50,000. Inside the bank, Gans asked a manager to alert authorities. Both the FBI and police were able to follow the car for a while, including use of aircraft, but lost track of it for a short time in a rural area of Miami-Dade County. Trial testimony showed that's when Muhammad shot the couple and tried to hide by burying himself, the rifle and the money in mud and weeds. Muhammad was found soon after and arrested. While awaiting trial, he and 10 other inmates escaped from jail, leading to a nationwide manhunt including a top 10 fugitives listing by the FBI.

Authorities say Muhammad was involved after his escape in the fatal October 1974 shooting of a liquor store clerk during an armed robbery in Cordele, Ga., that wounded a second clerk. He was never tried in that case. The FBI finally arrested Muhammad on New Year's Eve in 1974 in Florida.

Muhammad converted to Islam in prison, changing his name from Knight. During his 1996 resentencing, he cursed at the judge and lawyers and yelled "Allahu Akbar!" — "God is great" in Arabic.

Following is a list of inmates executed since Florida resumed executions in 1979:

1. John Spenkelink, 30, executed May 25, 1979, for the murder of traveling companion Joe Szymankiewicz in a Tallahassee hotel room.

2. Robert Sullivan, 36, died in the electric chair Nov. 30, 1983, for the April 9, 1973, shotgun slaying of Homestead hotel-restaurant assistant manager Donald Schmidt.

3. Anthony Antone, 66, executed Jan. 26, 1984, for masterminding the Oct. 23, 1975, contract killing of Tampa private detective Richard Cloud.

4. Arthur F. Goode III, 30, executed April 5, 1984, for killing 9-year-old Jason Verdow of Cape Coral March 5, 1976.

5. James Adams, 47, died in the electric chair on May 10, 1984, for beating Fort Pierce millionaire rancher Edgar Brown to death with a fire poker during a 1973 robbery attempt.

6. Carl Shriner, 30, executed June 20, 1984, for killing 32-year-old Gainesville convenience-store clerk Judith Ann Carter, who was shot five times.

7. David L. Washington, 34, executed July 13, 1984, for the murders of three Dade County residents _ Daniel Pridgen, Katrina Birk and University of Miami student Frank Meli _ during a 10-day span in 1976.

8. Ernest John Dobbert Jr., 46, executed Sept. 7, 1984, for the 1971 killing of his 9-year-old daughter Kelly Ann in Jacksonville..

9. James Dupree Henry, 34, executed Sept. 20, 1984, for the March 23, 1974, murder of 81-year-old Orlando civil rights leader Zellie L. Riley.

10. Timothy Palmes, 37, executed in November 1984 for the Oct. 19, 1976, stabbing death of Jacksonville furniture store owner James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Ronald John Michael Straight, executed May 20, 1986.

11. James David Raulerson, 33, executed Jan. 30, 1985, for gunning down Jacksonville police Officer Michael Stewart on April 27, 1975.

12. Johnny Paul Witt, 42, executed March 6, 1985, for killing, sexually abusing and mutilating Jonathan Mark Kushner, the 11-year-old son of a University of South Florida professor, Oct. 28, 1973.

13. Marvin Francois, 39, executed May 29, 1985, for shooting six people July 27, 1977, in the robbery of a ``drug house'' in the Miami suburb of Carol City. He was a co-defendant with Beauford White, executed Aug. 28, 1987.

14. Daniel Morris Thomas, 37, executed April 15, 1986, for shooting University of Florida associate professor Charles Anderson, raping the man's wife as he lay dying, then shooting the family dog on New Year's Day 1976.

15. David Livingston Funchess, 39, executed April 22, 1986, for the Dec. 16, 1974, stabbing deaths of 53-year-old Anna Waldrop and 56-year-old Clayton Ragan during a holdup in a Jacksonville lounge.

16. Ronald John Michael Straight, 42, executed May 20, 1986, for the Oct. 4, 1976, murder of Jacksonville businessman James N. Stone. He was a co-defendant with Timothy Palmes, executed Jan. 30, 1985.

17. Beauford White, 41, executed Aug. 28, 1987, for his role in the July 27, 1977, shooting of eight people, six fatally, during the robbery of a small-time drug dealer's home in Carol City, a Miami suburb. He was a co-defendant with Marvin Francois, executed May 29, 1985.

18. Willie Jasper Darden, 54, executed March 15, 1988, for the September 1973 shooting of James C. Turman in Lakeland.

19. Jeffrey Joseph Daugherty, 33, executed March 15, 1988, for the March 1976 murder of hitchhiker Lavonne Patricia Sailer in Brevard County.

20. Theodore Robert Bundy, 42, executed Jan. 24, 1989, for the rape and murder of 12-year-old Kimberly Leach of Lake City at the end of a cross-country killing spree. Leach was kidnapped Feb. 9, 1978, and her body was found three months later some 32 miles west of Lake City.

21. Aubry Dennis Adams Jr., 31, executed May 4, 1989, for strangling 8-year-old Trisa Gail Thornley on Jan. 23, 1978, in Ocala.

22. Jessie Joseph Tafero, 43, executed May 4, 1990, for the February 1976 shooting deaths of Florida Highway Patrolman Phillip Black and his friend Donald Irwin, a Canadian constable from Kitchener, Ontario. Flames shot from Tafero's head during the execution.

23. Anthony Bertolotti, 38, executed July 27, 1990, for the Sept. 27, 1983, stabbing death and rape of Carol Ward in Orange County.

24. James William Hamblen, 61, executed Sept. 21, 1990, for the April 24, 1984, shooting death of Laureen Jean Edwards during a robbery at the victim's Jacksonville lingerie shop.

25. Raymond Robert Clark, 49, executed Nov. 19, 1990, for the April 27, 1977, shooting murder of scrap metal dealer David Drake in Pinellas County.

26. Roy Allen Harich, 32, executed April 24, 1991, for the June 27, 1981, sexual assault, shooting and slashing death of Carlene Kelly near Daytona Beach.

27. Bobby Marion Francis, 46, executed June 25, 1991, for the June 17, 1975, murder of drug informant Titus R. Walters in Key West.

28. Nollie Lee Martin, 43, executed May 12, 1992, for the 1977 murder of a 19-year-old George Washington University student, who was working at a Delray Beach convenience store.

29. Edward Dean Kennedy, 47, executed July 21, 1992, for the April 11, 1981, slayings of Florida Highway Patrol Trooper Howard McDermon and Floyd Cone after escaping from Union Correctional Institution.

30. Robert Dale Henderson, 48, executed April 21, 1993, for the 1982 shootings of three hitchhikers in Hernando County. He confessed to 12 murders in five states.

31. Larry Joe Johnson, 49, executed May 8, 1993, for the 1979 slaying of James Hadden, a service station attendant in small north Florida town of Lee in Madison County. Veterans groups claimed Johnson suffered from post-traumatic stress syndrome.

32. Michael Alan Durocher, 33, executed Aug. 25, 1993, for the 1983 murders of his girlfriend, Grace Reed, her daughter, Candice, and his 6-month-old son Joshua in Clay County. Durocher also convicted in two other killings.

33. Roy Allen Stewart, 38, executed April 22, 1994, for beating, raping and strangling of 77-year-old Margaret Haizlip of Perrine in Dade County on Feb. 22, 1978.

34. Bernard Bolander, 42, executed July 18, 1995, for the Dade County murders of four men, whose bodies were set afire in car trunk on Jan. 8, 1980.

35. Jerry White, 47, executed Dec. 4, 1995, for the slaying of a customer in an Orange County grocery store robbery in 1981.

36. Phillip A. Atkins, 40, executed Dec. 5, 1995, for the molestation and rape of a 6-year-old Lakeland boy in 1981.

37. John Earl Bush, 38, executed Oct. 21, 1996, for the 1982 slaying of Francis Slater, an heir to the Envinrude outboard motor fortune. Slater was working in a Stuart convenience store when she was kidnapped and murdered.

38. John Mills Jr., 41, executed Dec. 6, 1996, for the fatal shooting of Les Lawhon in Wakulla and burglarizing Lawhon's home.

39. Pedro Medina, 39, executed March 25, 1997, for the 1982 slaying of his neighbor Dorothy James, 52, in Orlando. Medina was the first Cuban who came to Florida in the Mariel boat lift to be executed in Florida. During his execution, flames burst from behind the mask over his face, delaying Florida executions for almost a year.

40. Gerald Eugene Stano, 46, executed March 23, 1998, for the slaying of Cathy Scharf, 17, of Port Orange, who disappeared Nov. 14, 1973. Stano confessed to killing 41 women.

41. Leo Alexander Jones, 47, executed March 24, 1998, for the May 23, 1981, slaying of Jacksonville police Officer Thomas Szafranski.

42. Judy Buenoano, 54, executed March 30, 1998, for the poisoning death of her husband, Air Force Sgt. James Goodyear, Sept. 16, 1971.

43. Daniel Remeta, 40, executed March 31, 1998, for the murder of Ocala convenience store clerk Mehrle Reeder in February 1985, the first of five killings in three states laid to Remeta.

44. Allen Lee ``Tiny'' Davis, 54, executed in a new electric chair on July 8, 1999, for the May 11, 1982, slayings of Jacksonville resident Nancy Weiler and her daughters, Kristina and Katherine. Bleeding from Davis' nose prompted continued examination of effectiveness of electrocution and the switch to lethal injection.

45. Terry M. Sims, 58, became the first Florida inmate to be executed by injection on Feb. 23, 2000. Sims died for the 1977 slaying of a volunteer deputy sheriff in a central Florida robbery.

46. Anthony Bryan, 40, died from lethal injection Feb. 24, 2000, for the 1983 slaying of George Wilson, 60, a night watchman abducted from his job at a seafood wholesaler in Pascagoula, Miss., and killed in Florida.

47. Bennie Demps, 49, died from lethal injection June 7, 2000, for the 1976 murder of another prison inmate, Alfred Sturgis. Demps spent 29 years on death row before he was executed.

48. Thomas Provenzano, 51, died from lethal injection on June 21, 2000, for a 1984 shooting at the Orange County courthouse in Orlando. Provenzano was sentenced to death for the murder of William ``Arnie'' Wilkerson, 60.

49. Dan Patrick Hauser, 30, died from lethal injection on Aug. 25, 2000, for the 1995 murder of Melanie Rodrigues, a waitress and dancer in Destin. Hauser dropped all his legal appeals.

50. Edward Castro, died from lethal injection on Dec. 7, 2000, for the 1987 choking and stabbing death of 56-year-old Austin Carter Scott, who was lured to Castro's efficiency apartment in Ocala by the promise of Old Milwaukee beer. Castro dropped all his appeals.

51. Robert Glock, 39 died from lethal injection on Jan. 11, 2001, for the kidnapping murder of a Sharilyn Ritchie, a teacher in Manatee County. She was kidnapped outside a Bradenton shopping mall and taken to an orange grove in Pasco County, where she was robbed and killed. Glock's co-defendant Robert Puiatti remains on death row.

52. Rigoberto Sanchez-Velasco, 43, died of lethal injection on Oct. 2, 2002, after dropping appeals from his conviction in the December 1986 rape-slaying of 11-year-old Katixa ``Kathy'' Ecenarro in Hialeah. Sanchez-Velasco also killed two fellow inmates while on death row.

53. Aileen Wuornos, 46, died from lethal injection on Oct. 9, 2002, after dropping appeals for deaths of six men along central Florida highways.

54. Linroy Bottoson, 63, died of lethal injection on Dec. 9, 2002, for the 1979 murder of Catherine Alexander, who was robbed, held captive for 83 hours, stabbed 16 times and then fatally crushed by a car.

55. Amos King, 48, executed by lethal inection for the March 18, 1977 slaying of 68-year-old Natalie Brady in her Tarpon Spring home. King was a work-release inmate in a nearby prison.

56. Newton Slawson, 48, executed by lethal injection for the April 11, 1989 slaying of four members of a Tampa family. Slawson was convicted in the shooting deaths of Gerald and Peggy Wood, who was 8 1/2 months pregnant, and their two young children, Glendon, 3, and Jennifer, 4. Slawson sliced Peggy Wood's body with a knife and pulled out her fetus, which had two gunshot wounds and multiple cuts.

57. Paul Hill, 49, executed for the July 29, 1994, shooting deaths of Dr. John Bayard Britton and his bodyguard, retired Air Force Lt. Col. James Herman Barrett, and the wounding of Barrett's wife outside the Ladies Center in Pensacola.

58. Johnny Robinson, died by lethal injection on Feb. 4, 2004, for the Aug. 12, 1985 slaying of Beverly St. George was traveling from Plant City to Virginia in August 1985 when her car broke down on Interstate 95, south of St. Augustine. He abducted her at gunpoint, took her to a cemetery, raped her and killed her.

59. John Blackwelder, 49, was executed by injection on May 26, 2004, for the calculated slaying in May 2000 of Raymond Wigley, who was serving a life term for murder. Blackwelder, who was serving a life sentence for a series of sex convictions, pleaded guilty to the slaying so he would receive the death penalty.

60. Glen Ocha, 47, was executed by injection April 5, 2005, for the October, 1999, strangulation of 28-year-old convenience store employee Carol Skjerva, who had driven him to his Osceola County home and had sex with him. He had dropped all appeals.

61. Clarence Hill 20 September 2006 lethal injection Stephen Taylor

62. Arthur Dennis Rutherford 19 October 2006 lethal injection Stella Salamon

63. Danny Rolling 25 October 2006 lethal injection Sonja Larson, Christina Powell, Christa Hoyt, Manuel R. Taboada, and Tracy Inez Paules

64. Ángel Nieves Díaz 13 December 2006 lethal injection Joseph Nagy

65. Mark Dean Schwab 1 July 2008 lethal injection Junny Rios-Martinez, Jr.

66. Richard Henyard 23 September 2008 lethal injection Jamilya and Jasmine Lewis

67. Wayne Tompkins 11 February 2009 lethal injection Lisa DeCarr

68. John Richard Marek 19 August 2009 lethal injection Adela Marie Simmons

69. Martin Grossman 16 February 2010 lethal injection Margaret Peggy Park

70. Manuel Valle 28 September 2011 lethal injection Louis Pena

71. Oba Chandler 15 November 2011 lethal injection Joan Rogers, Michelle Rogers and Christe Rogers

72. Robert Waterhouse 15 February 2012 lethal injection Deborah Kammerer

73. David Alan Gore 12 April 2012 lethal injection Lynn Elliott

74. Manuel Pardo 11 December 2012 lethal injection Mario Amador, Roberto Alfonso, Luis Robledo, Ulpiano Ledo, Michael Millot, Fara Quintero, Fara Musa, Ramon Alvero, Daisy Ricard.

75. Larry Eugene Mann 10 April 2013 lethal injection Elisa Nelson

76. Elmer Leon Carroll 29 May 2013 lethal injection Christine McGowan

77. William Edward Van Poyck 12 June 2013 lethal injection Ronald Griffis

78. John Errol Ferguson 05 August 2013 lethal injection Livingstone Stocker, Michael Miller, Henry Clayton, John Holmes, Gilbert Williams, and Charles Cesar Stinson

79. Marshall Lee Gore 01 October 2013 lethal injection Robyn Novick (also killed Susan Roark but was executed for killing Novick)

80. William Frederick Happ 15 October 2013 lethal injection Angie Crowley

81. Darius Kimbrough 12 November 2013 Lethal Injection Denise Collins

82. Thomas Knight a/k/a Askari Abdullah Muhammad 7 January 2014 lethal injection Sydney and Lillian Gans, Florida Department of Corrections officer Richard Burke

On July 17, 1974, Askari Abdullah Muhammad (who then was named Thomas Knight) kidnapped and murdered Sydney and Lillian Gans near Miami, Florida. When Sydney arrived at work that Wednesday morning and parked his Mercedes Benz car, Knight ambushed him and ordered him back into the car. Knight commanded Sydney to drive home and pick up his wife, Lillian, and then to drive to a bank and retrieve $50,000 in cash.

Sydney went inside the bank to retrieve the money, but he also told the bank president that Knight was holding him and his wife hostage. The bank president alerted the police and Federal Bureau of Investigation. Knight then forced Sydney and Lillian to drive toward a secluded area on the outskirts of Miami. Police officers in street clothes shadowed the Mercedes in unmarked cars. A helicopter and a small fixed-wing surveillance airplane also eventually joined the surveillance. The officers followed the vehicle, but they lost sight of the car for about four or five minutes. During that time, Knight killed Sydney and Lillian with gunshots to the neck that he fired from the back seat of the car.

The police found the vehicle sitting in a construction area with the front passenger door, the right rear passenger door, and the trunk open. Police saw Knight running away from the vehicle and toward a wooded area with an automatic rifle in his hands. Police found the dead body of Lillian behind the steering wheel and the dead body of Sydney about 25 feet from the vehicle.

About four hours later, police apprehended Knight about 2,000 feet from the vehicle. Knight had blood stains on his pants; buried beneath him in the dirt were an automatic rifle and a paper bag containing $50,000.

In September 1974, Knight escaped from prison. After a massive nationwide manhunt, police finally captured Knight in December 1974. In 1975, a Florida jury convicted Knight of the murders of Sydney and Lillian, and the trial judge sentenced him to death.

In 1980, while Knight’s petition for post conviction relief was pending before Florida state courts, Knight killed again. This time, he fatally stabbed a prison guard, Officer James Burke with the sharpened end of a spoon. Knight killed Burke because he was upset that he had been denied permission to meet with a visitor. Knight was convicted and sentenced to death for that murder too. Richard Burke had only been an officer at the Florida State Prison for four months when he was killed. He was survived by his wife and two children.

UPDATE: Stayed pending a challenge over the drugs to be used in the lethal injection. These challenges are routinely failing so this stay is expected to be lifted.

Florida Commission on Capital Cases

Knight, Thomas (aka Askari Muhammad)

DC# 017434

DOB: 02-04-51

Cases

Case Number: 74-5978

Judge: Lopez

County: Dade

Attorney: Doss

Case Number: 80-341-CF-A

Judge: Chance

County: Bradford

Attorney: McDermott

Eleventh Judicial Circuit, Dade County, Case# 74-5978

Sentencing Judge: The Honorable Gene Williams

Resentencing Judge: The Honorable Rodolfo Sorondo

Attorneys, Trial: James Mathews – Private

Attorney, Direct Appeal: William J. Hutchinson – Private

Attorney, Direct Appeal (Resentencing): Louis Campbell – Assistant Public Defender

Attorneys, Collateral Appeals: D. Todd Doss – Pro-Bono ; D. Todd Doss & Linda McDermott

Date of Offense: 07/17/74

Date of Resentence: 03/12/96

Circumstances of the Offense:

On 07/17/74 the victim, Sydney Gans, arrived at his place of business and parked his automobile. The defendant Thomas Knight, a former employee, who was carrying an automatic rifle, approached him. Knight then ordered Mr. Gans to get back into the vehicle and drive to his residence and pick up his wife, Lillian Gans. Once Mrs. Gans was in the vehicle Knight ordered Mr. Gans to drive to his bank in order to obtain $50,000. Mr. Gans did as instructed and entered the bank. While inside the bank Mr. Gans notified the bank president of the abduction, and the police and FBI were alerted. Mr. Gans then returned to his wife and their car with the money. The defendant then ordered Mrs. Gans to drive the car in an evasive route toward South Dade County. The FBI and local law enforcement were in pursuit, and had remained undetected, however they briefly lost sight of the vehicle. The defendant ordered the couple to stop the vehicle in a remote area and then shot both victims in the back of the head at close range. The defendant fled the scene, but was apprehended shortly thereafter. Knight attempted to hide from the police by burying himself in the dirt and weeds of a heavily wooded area. Police noticed bloodstains on the defendant’s pants and discovered the automatic rifle and $50,000 hidden underneath him.

Additional Information:

On 09/19/74, while awaiting his trial, the defendant along with ten inmates escaped from the Dade County Jail. The defendant was placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List and an extensive manhunt ensued.

While on escape status the defendant allegedly committed a murder and armed robbery in Cordele, Georgia. (Crisp County) The following circumstances were received from the Crisp County Authorities: Knight and another subject committed an Armed Robbery, Murder and Aggravated Battery. On 10/21/74, they both entered a liquor store and asked for a bottle. As the clerk retrieved the bottle, he was told to hand over the money. The defendant and codefendant then demanded both clerks’ wallets and started shooting. Mr. William Culpepper was shot three times and was killed; Mr. A.V. Norton was shot twice. The defendant and codefendant fled taking $641.00. FBI agents arrested the subject in New Smyrna Beach, FL on 12/31/74. At the time of his arrest the subject was in possession of a sawed-off shotgun, a .38 caliber revolver and a 9mm automatic. These weapons were reported stolen from Titusville, FL. Previous reports indicate that Georgia authorities did not prosecute the subject due to his Florida death sentence. The subject’s codefendant was charged with only the Aggravated Battery charge.

Knight was arrested and stood trial for the fatal stabbing of a prison guard while he was incarcerated on death row (CC# 80-341CF); the murder occurred on 10/12/80. Knight was convicted and sentenced to death for this offense on 01/20/83. Knight’s new sentencing date in 1996 is the starting point for all subsequent appeals, although he was initially sentenced over 25 years ago.

There have been mental health issues throughout this case most of which were presented to the trial court. Numerous mental health experts have testified on Knight’s behalf, claiming that he has longstanding mental health problems that may include schizophrenia. Experts for the State determined that Knight did, in fact, have a personality disorder but was a “malingerer” and not schizophrenic. Knight was determined competent to stand trial. There has not been any executive intervention relating to Knight’s alleged mental illness.

Trial Summary:

08/30/74 Defendant arraigned, entered a plea of not guilty.

09/19/74 Prior to trial, defendant escaped from jail.

12/31/75 Defendant captured and returned to jail.

01/06/75 PD dismissed due to conflict, Court appointed Special Counsel James Mathews.

04/01/75 Plea of Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity entered.

04/19/75 Defendant found guilty by the trial jury of two counts of First-Degree Murder, as charged in the indictment. Upon advisory sentencing the Jury, by a majority, recommended the death penalty.

04/21/75 Defendant was sentenced as follows: Count I: First-Degree Murder (Lillian Gans) – Death Count II: First-Degree Murder (Sydney Gans) – Death

01/18/96 Order to return defendant for resentencing.

02/01/96 Hearing held; Court found defendant competent to proceed.

02/08/96 Upon advisory sentencing, the jury recommended death sentence by a vote of 9-3

03/12/96 Resentenced as follows:

Count I: First-Degree Murder (Lillian Gans) – Death

Count II: First-Degree Murder (Sydney Gans) – Death

Appeal Summary:

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal

FSC# 47,599

338 So. 2d 201 (Fla.1976)

05/20/75 Appeal filed

09/30/76 FSC affirmed convictions and death sentence

Florida Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

FSC# 58,528

01/22/80 Petition filed

02/06/80 FSC transferred petition to trial court to be treated as a 3.850 Motion for PCR

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

CC# 74-5978

02/12/80 Motion received per Florida Supreme Court order on 02/06/80

08/15/80 Trial court dismissed motion, should be treated as a Habeas by the FSC

Florida Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

FSC# 59,741

394 So.2d 997 (Fla. 1981)

10/01/80 Petition filed

02/24/81 Petition denied

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

CC# 74-5978

02/20/81 Motion filed

08/25/81 Motion denied

United States District Court, Southern District – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

USDC# 81-391

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

FSC# 61,454

426 So. 2d 533 (Fla. 1982)

11/03/81 Appeal filed

04/11/83 Mandate issued

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC# 82-6865

06/09/83 Petition filed

10/06/83 Petition denied

United States Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit – Habeas Appeal

USCA# 86-5610

863 F 2d at 708

07/30/86 Appeal filed

09/06/89 Remanded to United States District Court to grant Habeas Petition.

09/06/89 Mandate issued

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal (Resentencing)

FSC# 87,783

721 So. 2d 287 (Fla. 1998)

04/22/96 Appeal filed

11/12/98 FSC affirmed conviction and death sentence

03/11/99 Rehearing denied

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC# 98-9741

528 U.S. 990; 120 S. Ct. 459 (1999)

06/09/99 Petition filed

11/08/99 Petition denied

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

CC# 74-5978

11/07/00 Motion filed

01/15/03 Motion denied

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

FSC# 03-631

923 So.2d 387

04/08/03 Appeal filed

11/03/05 FSC affirmed Circuit Court’s order denying 3.850 Motion

02/24/06 Rehearing denied

03/13/06 Mandate issued

Florida Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

FSC# 04-1366

923 So.2d 387

07/12/04 Petition filed

11/03/05 Petition denied

02/24/06 Rehearing denied

03/13/06 Mandate issued

United States District Court, Southern District – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

USDC# 06-20570 (Pending)

03/07/06 Petition filed

Case Information:

On 05/20/75, Knight filed a Direct Appeal to the Florida Supreme Court. Among several issues raised, Knight claimed the trial court erred in the denial of his challenge for cause as to the impartiality of a juror. Second, Knight claimed the trial court erred in denying his motion for additional peremptory challenges because of pervasive pre-trial publicity. Third, Knight alleged the trail court erred in allowing the State to prosecute the charges under a theory of felony murder when the indictment charged premeditated murder to be absolutely contrary to established precedent. Fourth, Knight claimed the introduction of the testimony of Mr. Gill (the bank president), to the effect that Mr. Gans (the victim) had told him that he had been kidnapped and his wife was being held for $50,000 ransom and describing what had occurred thus far, into evidence was error as it was not within the res gestae of the crime charged. Finally, he claimed the trial court erred in denying his motion for change of venue. Having carefully evaluated all other points raised on appeal by appellant, the Court found none of them meritorious as to constitute reversible error. Furthermore, the allegations of the indictment were sufficient to charge Knight with First-Degree murder. On 09/30/76, the Court affirmed Knight’s convictions and sentence.

Knight filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus to the Florida Supreme Court on 01/22/80. On 02/06/80, the Court transferred the petition to the trial court and ordered that it be treated as a 3.850 Motion for Post Conviction Relief. On 02/12/80, the trial court received and reviewed the motion. On 08/15/80, the trial court dismissed the motion, determined it was properly filed originally as a Habeas Petition, and requested that it be properly filed to the Florida Supreme Court. On 10/01/80, Knight filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus to the Florida Supreme Court, who acknowledged the trial court was correct in determining the appeal should be processed as a Habeas Petition. However, the Court denied the Petition on 02/24/81. On 02/20/81, Knight filed a 3.850 Motion to the Circuit Court, which was denied on 08/25/081. Knight filed a 3.850 Appeal to the Florida Supreme Court on 11/03/81. The Court affirmed the trial court’s denial of the 3.850 Motion on 12/16/82. The rehearing was denied on 03/02/83. The mandate was issued on 04/11/83. On 02/24/81, Knight filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus to the United States District Court, Southern District. The Court held the Petition and granted a Stay of Execution on 02/26/81. The Court retained jurisdiction over the petition and ordered Knight to exhaust his appeals in State court. The Petition was dismissed on 06/27/86. On 06/09/83, Knight filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Supreme Court, which was denied on 10/06/83.

On 07/30/86, Knight filed a Habeas Appeal to the United States Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit. On 09/06/89, the Court remanded the case to the trial court for resentencing based on a Hitchcock error, which requires the courts to consider non-statutory, as well as statutory mitigating evidence proffered by a capital defendant. This decision was made prior to the Supreme Court’s decision in Hitchcock, and was originally made in accordance with Lockett.

Knight filed a Direct Appeal after resentencing to the Florida Supreme Court on 04/22/96. On 11/112/98, the Court affirmed the conviction and sentence. The rehearing was denied on 03/11/99. On 06/09/99, Knight filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Supreme Court, which was denied on 11/08/99. On 11/07/00, Knight filed a 3.850 Motion to the Circuit Court, which was denied on 01/15/03.

On 04/08/03, Knight filed a 3.850 Appeal to the Florida Supreme Court. Upon careful review of Knight’s motion, the Court found no error in the Circuit Court’s determination that denial was appropriate on each claim made by Knight. On 11/03/05, the Court affirmed the Circuit Court’s denial of the 3.850 Motion because Knight’s claims are either procedurally barred, conclusively refuted by the record, facially or legally insufficient as alleged, or without merit as a matter of law. On 02/24/06, the rehearing was denied. The mandate was issued on 03/13/06.

On 07/12/04, Knight filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus to the Florida Supreme Court. The petition was denied on 11/03/05 because Knight raised the same issues that were raised in his 3.850 Appeal, which cannot be relitigated in the Habeas Petition. On 02/24/06, the rehearing was denied. The mandate was issued on 03/13/06. On 03/06/07, Knight filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus in the United States District Court, Southern District. This petition is currently pending. KNIGHT, Thomas (B/M) AKA: Askari Abdullah Muhammad

Eighth Judicial Circuit, Bradford County, Case# 80-341CF

Sentencing Judge: The Honorable Chester B. Chance

Trial Attorney: Pro se

Attorney, Direct Appeal: David Davis – Assistant Public Defender

Attorney, Collateral Appeals: D. Todd Doss & Linda McDermott – Registry and Federal

Date of Offense: 10/12/80

Date of Sentence: 01/20/83

Circumstances of the Offense:

On 10/12/80 at 9:45 a.m., a guard at the Florida State Prison, told the subject, a death row inmate in Dade County Case# F74-5978, that he had a visitor; however, prior to the approval of the visit, he must shave in compliance with prison regulations. He refused to comply and therefore was denied the visit. When the guard was exiting, he and another guard overheard the subject state, “Well, it looks like I will have to start sticking people.” Later, Officer Burke, the victim, was escorting the death row inmates to the showers. When he unlocked the subject’s cell, the subject attacked him with a homemade knife (a sharpened spoon). While this was occurring, another officer overheard the screams of Officer Burke and called for help. Within seconds, two other officers were present and observed Officer Burke lying on his back trying to fend off the subject’s blows. The subject complied with an order to back off, and discarded the weapon in a trash container. More than a dozen wounds were inflicted on Officer Burke, with one being a fatal stab wound to the heart.

Trial Summary:

12/03/80 Original counsel Joseph H. Forbes dismissed as Special Appointed Counsel.

12/03/80 Susan Cary remained as counsel of record.

12/17/80 Steven Bernstein appointed as co-counsel.

01/21/81 Judge R.A. Green Jr. recused himself.

01/22/81 Judge Wayne M. Carlisle appointed.

05/25/82 Trial ended in a mistrial.

05/26/82 Judge Wayne M. Carlisle recused himself. Reassigned to Judge Chester B. Chance

06/07/82 Court ordered that the defendant was competent to stand trial.

06/15/82 Ggranted motion to allow defendant to represent himself.

06/15/82 Stephen Bernstein was discharged as legal counsel. (standby)

07/20/80 Court granted motion for Stephen Bernstein to be relieved as standby counsel.

10/26/82 Defendant was found guilty (under the name of Askari Abdullah Muhammad) by jury

of First-Degree Murder as charged in the indictment. Defendant waived consideration by the jury

of an advisory sentence; therefore, the cause proceeded to the Court without the jury recommendation.

01/20/83 The defendant was sentenced as followed: Count I: First-Degree Murder – Death

Appeal Summary:

Florida Supreme Court – Direct Appeal

FSC# 63,343

494 So. 2d 969 (Fla. 1986)

10/01/84 Appeal filed

07/17/86 FSC affirmed conviction and death sentence

10/22/86 Motion for rehearing denied

11/25/86 Mandate issued

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC# 86-6092

497 U.S. 1101 (1987)

01/09/87 Petition filed

02/23/87 Petition denied

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion

CC# 80-34CF

02/23/89 Motion filed

08/31/89 Motion denied

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

FSC# 75,055

603 So. 2d 488 (Fla. 1992)

11/27/89 Appeal filed

06/11/92 FSC reversed and remanded for an evidentiary hearing

09/17/92 Rehearing denied and mandate issued

State Circuit Court – 3.850 Motion (On Remand from FSC)

CC# 80-34CF

09/17/92 Appeal filed

06/12/00 Evidentiary hearing held

05/21/01 Trial court granted PCR, ordered new sentencing hearing

Florida Supreme Court – Appeal of 3.850 Motion (Filed by State)

FSC# 01-1415

866 So. 2d 1195

06/26/01 Appeal filed

08/21/03 FSC reversed the trial court’s order vacating death sentence

Florida Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

FSC# 02-1106

866 So. 2d 1195

05/13/02 Petition filed

08/21/03 Petition denied

01/20/04 Mandate issued

United States Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC# 03-9494

124 S. Ct. 2396; 158 L. Ed. 2d 969 (2004)

03/18/04 Petition filed

05/24/04 Petition denied

United States District Court, Middle District – Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus

USDC# 05-62

01/18/05 Petition filed

03/26/08 Petition denied; dismissed with prejudice

07/02/08 Certificate of Appealability filed

08/25/08 Certificate denied

United States Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit – Habeas Appeal

USCA# 08-13495

06/16/08 Appeal filed

01/09/09 Certificate of Appealability denied

United State Supreme Court – Petition for Writ of Certiorari

USSC# 09-5401

130 S.Ct. 1281

07/13/09 Petition filed

01/25/10 Petition denied

Circuit Court – 3.851 Motion

CC# 80-341CF

07/24/08 Motion filed

09/09/08 Motion denied

Florida Supreme Court – 3.850 Appeal

FSC# 09-170

22 So.3d 538

02/02/09 Appeal filed

11/05/09 FSC affirmed the disposition of the lower court

Case Information:

Knight filed a Direct Appeal to the Florida Supreme Court on 10/01/84. Among several issues that were raised, Knight claimed the trial court failed to follow the dictates of Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure 3.210, a rule which requires the court to appoint “no more than three and no fewer than two experts” to examine the defendant. Second, Knight claimed that he did not know the purpose of the competency examination, and that neither his attorney nor competency examiner informed him of the reason for the interview. Third, Knight also claimed the competency report failed to include matters required by Florida Rules of Criminal Procedure 3.216(e) and 3.211(a)(1). Finally, Knight claimed the trial court improperly applied two aggravating factors when it found that he was under a sentence of imprisonment and that he had been convicted of a violent or capital felony. On 07/17/86, the Court affirmed Knight’s convictions and sentence. On 10/22/86, the rehearing was denied. The mandate was issued on 11/25/86

On 01/09/87, Knight filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Supreme Court, which was denied on 02/23/87. On 02/23/89, Knight filed a 3.850 Motion to the Circuit Court, which was denied on 08/31/89. Knight filed a 3.850 Appeal to the Florida Supreme Court on 11/27/89. The Court reversed the trial court’s ruling and remanded the case back to the trial court for an evidentiary hearing, regarding their ruling on a Brady violation. The evidentiary hearing (on remand from the Florida Supreme Court) was held on 06/12/00. The delay in proceeding with the evidentiary hearing was related to the United States Court of Appeals ordering the defendant to be resentenced in his Dade County case. Subsequent to the evidentiary hearing, the trial court, on 08/21/03, ordered the defendant to be resentenced. The State appealed the trial court’s decision to the Florida Supreme Court on 06/26/01. On 08/21/03, the Court issued an opinion in which they reversed the trial court’s order which vacated Knight’s death sentence. The opinion also denied a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus, which Muhammad had filed on 05/13/02. The mandate for the Habeas was issued on 01/20/04. Knight filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Supreme Court on 03/18/04, which was denied on 05/24/04. On 01/18/05, Knight filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus to the United States District Court, Middle District, which was denied on 03/26/08 and dismissed with prejudice. A Certificate of Appealability of was filed on 07/02/08 and denied on 08/25/08. Knight filed a Habeas appeal in the United States Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit on 06/16/08. The Certificate of Appealability was denied on 01/09/09. Knight filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Supreme Court on 07/13/09. The petition was denied on 01/25/10. On 07/24/08, Knight filed a 3.851 Motion in the Circuit Court. This motion was denied on 09/09/08. On 02/02/09, Knight filed a 3.850 Appeal in the Florida Supreme Court. The disposition of the lower court was affirmed on 11/05/09.

Knight v. State, 338 So.2d 201 (Fla. 1976). (Direct Appeal-Gans)

Defendant was convicted in Circuit Court, Dade County, Gene Williams, J., of first-degree murder and sentenced to death, and he appealed. The Supreme Court held, inter alia, that certain testimony was properly admitted as part of the res gestae of the crime charged; that the trial court did not err in allowing the State to prosecute the charges under a theory of felony-murder when the indictment charged premeditated murder; and that imposition of the death penalty was warranted. Affirmed.

PER CURIAM.

This cause is before us on direct appeal to review the convictions of Thomas Knight on two counts of murder in the first degree and sentence to death. We have jurisdiction pursuant to Article V, Section 3(b)(1), Florida Constitution.

Appellant was indicted for the first degree murder of Lillian and Sydney Gans in that he did kill and murder them from premeditated design by shooting them with a rifle. Briefly the facts leading up to the murder and defendant's apprehension by the authorities are as follows. Upon arriving at his place of business and parking in his designated space, Mr. Gans was approached by the defendant who was carrying an automatic rifle and was told to re-enter his automobile, to drive home and get Mrs. Gans, and to drive to the bank and get $50,000. While inside the bank, Mr. Gans informed the president about the abduction. The police and FBI were alerted. Mr. Gans then returned to his car with the money. He and his wife, shortly thereafter, were found shot to death, the fatal shots-perforating through their necks-having been fired from the rear seat of the vehicle. Thereafter, appellant was apprehended and taken into custody in a weeded area about 2,000 feet from the Gans' vehicle. Underneath him buried in the dirt was an automatic rifle and a paper bag containing $50,000. There were blood stains on his pants.

After an extensive trial, the jury returned verdicts of guilty of both counts of murder in the first degree and, after separate hearing on sentencing, recommended the death penalty be imposed. The trial judge agreed that under the circumstances the death penalty was the appropriate sentence and wrote his order on sentence carefully evaluating the mitigating and aggravating circumstances, stating in part: ‘1. That the aggravating circumstances found by the Court to be present and listed by the Court with the lettering as set forth in Florida Statute 921.141(5), are as follows: ‘(d) That the capital felonies were committed while the defendant was engaged in the commission of or in flight after committing the crime of kidnapping of Lillian Gans, and/or the robbery of Sidney Gans. ‘(e) That the capital felonies were committed for the purpose of avoiding or preventing a lawful arrest. ‘(f) That the capital felonies were committed for pecuniary gain. ‘(h) That the capital felonies were especially heinous, atrocious or cruel.

‘It might be considered a close question as to whether these murders were especially heinous, atrocious or cruel, because of the fact that when the defendant actually killed the victims, death was almost instantaneous. However, the Court is of the opinion that the hours preceding the actual killings constituted exceedingly cruel treatment of the victims. Mr. Gans was continually under severe strain, not only thinking of his own life but that of his wife. Mrs. Gans was also under continuous strain. Mr. and Mrs. Gans proceeded to follow the directions of the defendant hoping to escape death, although probably fearing for their lives at every instant. When it became apparent to them that the defendant was forcing them to a deserted area, it probably also became apparent to them they were going to be murdered. This feeling no doubt continued up to the actual moment of the deaths. Mr. Gans' actions were particularly noteworthy. After the initial danger, he could have escaped when directed by defendant to the bank. However, Mr. Gans, with commendable courage, attempting to save the life of his wife, again voluntarily submitted himself to the control of the defendant, only to lose his life together with his wife. All of these circumstances constitute particularly cruel, heinous and atrocious actions by the defendant when he finally shot the victims.

‘3. That as to mitigating circumstances, the Court finds as follows: ‘(a) the defendant has a history of prior criminal activity. ‘(b) the defendant was not under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance when the capital felonies were committed. ‘(c) the victims were not participants in the defendant's conduct nor did they consent to his acts. ‘(d) the defendant was not an accomplice in the capital felonies committed by another person and his participation was not relatively minor. ‘(e) the defendant did not act under extreme duress or under the substantial domination of another person. ‘(f) the capacity of the defendant to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of law was not substantially impaired. ‘(g) the age of the defendant at the time of the crime was 23 years. The Court finds age not to be a mitigating circumstance. The Court finds that the defendant is of at least average intelligence and experience as an adult.

‘. . . The Court finds, as did the jury, that the defendant is legally sane, knows right from wrong, knows the nature and consequences of his actions and did at the time of the commission of the two murders.’

Twenty three points have been stated as points on appeal by appellant although not all of these points are argued. Careful review of the briefs and voluminous transcript of record reveal that none of these contentions constitutes reversible error.

Appellant urges error in the trial court's denial of his challenge for cause as to the impartiality of a juror. Preliminarily, it must be noted that the record does not reveal any challenge for cause of Juror Hochstadt. The record examination of Juror Hochstadt does not indicate any showing of partiality toward the State. In fact, the record evidences that the subject juror had formed no opinion as to the guilt or innocence of the defendant and would be completely impartial.

The trial court did not err in denying appellant's motion for additional peremptory challenges because of pervasive pre-trial publicity. He expressly determined that no showing of prejudice had been made. Additionally we note that the record clearly shows that the trial judge was extremely liberal in excusing jurors for cause in order that an impartial trial would be secured.

Appellant's argument that the court erred in denying his motion for change of venue is without merit. He has failed to prove that he did not receive a fair and impartial trial and that the setting of his trial was inherently prejudicial. Recently, in Dobbert v. State, 328 So.2d 433 (Fla.1976), this Court restated the requirements set out by the Supreme Court of the United States in Murphy v. Florida, 421 U.S. 794, 95 S.Ct. 2031, 44 L.Ed.2d 589 (1975), relative to a fair and impartial trial, as follows:

‘The constitutional standard of fairness requires that a defendant have ‘a panel of impartial, ‘indifferent’ jurors.' Irvin v. Dowd, supra, 366 U.S. (717), at 722, 81 S.Ct. (1639), at 1642, (6 L.Ed.2d 751). Qualified jurors need not, however, be totally ignorant of the facts and issues involved. “To hold that the mere existence of any preconceived notion as to the guilt or innocence of an accused, without more, is sufficient to rebut the presumption of a prospective juror's impartiality would be to establish an impossible standard. It is sufficient if the juror can lay aside his impression or opinion and render a verdict based on the evidence presented in court.' Id., at 723, 81 S.Ct. (1639) at 1642. ‘At the same time, the juror's assurances that he is equal to this task cannot be dispositive of the accused's rights, and it remains open to the defendant to demonstrate ‘the actual existence of such an opinion in the mind of the juror as will raise the presumption of partiality.’ Ibid.

‘The Voir dire in this case indicates no such hostility to petitioner by the jurors who served in his trial as to suggest a partiality that could not be laid aside. Some of the jurors had a vague recollection of the robbery with which petitioner was charged and each had some knowledge of petitioner's past crimes, but none betrayed any belief in the relevance of petitioner's past to the present case. Indeed, four of the six jurors volunteered their views of its irrelevance, and one suggested that people who have been in trouble before are too often singled out for suspicion of each new crime-a predisposition that could only operate in petitioner's favor.’

Appellant submits that the introduction of the testimony of Mr. Gill, the bank president, to the effect that Mr. Gans, the deceased victim had told him that he had been kidnapped and his wife was being held for $50,000 ransom and describing what had occurred thus far, into evidence was error as it was not within the res gestae of the crime charged. The testimony given by Mr. Gill was admissible as being within the res gestae of the crime of kidnapping, one of the felonies enumerated in the felony murder statute, section 782.04(1)(a), Florida Statutes. The crime for which appellant was charged was murder in the first degree, and he could be tried and convicted under the indictment if the killing was committed by him in the perpetration of any robbery or kidnapping. The trial court properly held this evidence admissible as res gestae, an exception to the hearsay rule. Cf. State v. Williams, 198 So.2d 21 (Fla.1967), Campbell v. State, 227 So.2d 873 (Fla.1969).

We find appellant's allegation that the court erred in allowing the State to prosecute the chartges under a theory of felony murder when the indictment charged premeditated murder to be absolutely contrary to established precedent. In Larry v. State, 104 So.2d 352 (Fla.1958), this Court explained: ‘Furthermore, we think there was ample evidence to sustain a verdict for murder in the first degree committed in the perpetration of a robbery. The trial judge instructed the jury on this phrase of the law. His instruction was warranted by the evidence and in such a case premeditation is presumed as a matter of law. Leiby v. State, Fla., 50 So.2d 529. Proof of a homicide committed in the perpetration of the felonies set forth in s 782.04, Florida Statutes, F.S.A., may be shown under an indictment charging the unlawful killing of a human being from a premeditated design. Killen v. State, Fla., 92 So.2d 825; Everett v. State, Fla., 97 So.2d 241.’ (emphasis supplied)

Subsequently in Barton v. State, 193 So.2d 618 (Fla.App.2d 1967), authored by Justice Adkins while temporarily assigned to the District Court as an Associate Judge, that court opined and we agree: ‘The indictment was in the usual form charging murder to have been committed with a premeditated design to effect the death of Corbin. The appellant argues that he should have been furnished with a bill of particulars specifying whether the State would proceed on the theory of felony murder or premeditated murder. Without being apprised of the specific theory under which the State was electing to proceed, appellant says he was placed at a burdensome disadvantage by being forced to prepare defenses to each, which defenses necessarily are inconsistent. Appellant contends that forcing such a burden upon him constituted a denial of due process. ‘The allegations of the indictment were sufficient to charge murder in the first degree, regardless of whether the murder was committed in the perpetration of any of the felonies mentioned in F.S.A. s 782.04 or was committed with a premeditated design. Southworth v. State, 98 Fla. 1184, 125 So. 345. Under such a charge evidence under either theory may be introduced and defendant may be convicted either on the theory that the killing was carried out as a result of a premeditated design to effect death or on the theory of felony murder. Larry v. State, 104 So.2d 352 (Fla.1958).’ Cf. Hargrett v. State, 255 So.2d 298 (Fla.App. 3, 1971).

Having carefully evaluated all other points raised on appeal by appellant, we find none of them meritorious as to constitute reversible error. We have listened carefully to oral argument, examined and considered the record in light of the assignments of error and briefs filed and we have also, pursuant to Rule 6.16(b), Florida Appellate Rules, reviewed the evidence to determine whether the interests of justice require a new trial, with the result that we find no reversible error is made to appear and the evidence in the record, sub judice, does not reveal that the ends of justice require that a new trial be awarded.

Furthermore, we find appellant's position that the death penalty is not warranted under the particular facts of this case to be untenable. The atrocious, cruel, and heinous nature of the crimes committed by the appellant was carefully explained by the trial judge in his written findings of fact relative to the sentencing portion of this cause. Review of the record and consideration of the enumerated aggravating and mitigating circumstances support the conclusion that the death sentence recommended by the jury and imposed by the judge is appropriate under the particular facts of this cause.

Accordingly, no reversible error appearing, the judgments and sentence of the Circuit Court here under review are affirmed. It is so ordered. OVERTON, C.J., and ROBERTS, ADKINS, BOYD, SUNDBERG and HATCHETT, JJ., concur. ENGLAND, J., took no part in the consideration of this case.

Knight v. State, 394 So.2d 997 (Fla. 1981). (PCR-Gans)

Defendant, who had been convicted of murder and sentenced to death, submitted petition for writ of habeas corpus predicated on assertion of ineffective assistance of appellate counsel. The Supreme Court held that there was no substantial deficiency in representation of defendant on appeal by which defendant was prejudiced. Petition denied. Sundberg, C. J., concurred in result only.

PER CURIAM.

We have for consideration a petition for writ of habeas corpus by Thomas Knight whose conviction and sentence of death were affirmed by this Court in Knight v. State, 338 So.2d 201 (Fla.1976). We originally transferred this petition to the Eleventh Judicial Circuit and directed that it be treated as a motion for post-conviction relief. The trial judge in considering the petition properly determined that since petitioner's claim for relief is predicated on the assertion of ineffective assistance of appellate counsel, such relief can only be granted by habeas corpus in the appellate court unless it was caused by an act or omission of the trial court. The ineffective assistance of counsel allegations stem from acts or omissions before this Court, and therefore we have jurisdiction and will consider the petition for habeas corpus on its merits.

The Governor has signed a death warrant for petitioner's execution, which has been set for March 3, 1981. We received a motion for stay of execution and supporting briefs from the petitioner, Knight, as well as the extensive legal arguments contained in the petition for writ of habeas corpus. The state has filed a responding brief, and the Court has heard oral argument in the cause.

In summary, and for the reasons hereafter expressed, we deny the petition for writ of habeas corpus. We find that counsel on the initial appeal for the petitioner was court appointed and his representation was a result of state action. We have considered each of the asserted failures and omissions of this appellate counsel and have determined that the assertions individually and collectively are without merit. We expressly find that none of the asserted failures or omissions establish a serious incompetency that falls measurably below the performance expected of appellate counsel and that these specific asserted failures or omissions did not affect the outcome of the appellate proceedings to the prejudice of the appellant. We reach this conclusion and finding after a review of not only the record on this petition for habeas corpus but also the record on the initial appeal to this Court.

I. Facts in the Instant Case