49th murderer executed in U.S. in 2006

1053rd murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Alabama in 2006

35th murderer executed in Alabama since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

Larry Eugene Hutcherson a/k/a Larry Eugene Bonner W / M / 22 - 37 |

Irma Thelma Gray W / F / 89 |

06-19-99 |

Summary:

According to his confession at his 1996 retrial, Hutcherson broke into the home of 89 year old Irma Thelma Gray after taking Valium and drinking whiskey. When she returned home as he was ransacking the house, Hutcherson took a knife from the kitchen and killed her. An autopsy confirmed that she had been beaten and her throat cut so severely that she was almost decapitated. Hutcherson left his driver's license and other evidence at the crime scene. And he returned the next day to steal an air conditioner, microwave and more of Gray's belongings. According to his confession, he sold some and gave some away. After his first conviction was reversed, Hutcherson pled guilty to capital murder in 1996, and a Mobile County jury recommended the death penalty by an 11-1 vote. A judge adopted the jury's penalty. Hutcherson thanked the judge for the death sentence and his conviction became final on June 19, 1999.

Citations:

Hutcherson v. State, 677 So.2d 1174 (Ala.Cr.App. 1994) (Direct Appeal).

Ex parte Hutcherson, 677 So.2d 1205(Ala. 1996) (Direct Appeal - Reversed).

Hutcherson v. State, 727 So.2d 846 (Ala.Cr.App. 1997) (Direct Appeal).

Hutcherson v. Riley, --- F.3d ----, 2006 WL 3008401 (11th Circuit 2006) (Sec. 1983).

Final/Special Meal:

Hutcherson had a breakfast of grits and eggs, but made no request for a final meal. He said he would eat from a vending machine with family members.

Final Words:

"I'm so very sorry for hurting you like this. It's been a long time coming. If I could go back in time and change things, I most certainly would. I hope this gives you closure and someday find forgiveness for me."

Internet Sources:

Alabama Department of Corrections

Inmate: HUTCHERSON, LARRY EUGENE A

DOC#: 00Z547

Race: White

Gender: Male

Date of Birth: 9/3/1969

Location: Holman CF (Death Row)

Assigned to Death Row: 2/18/1993

County of Conviction: Mobile County

"Alabama killer executed for 1992 killing of elderly woman," by Garry Mitchell. (AP 10/26/2006, 11:16 p.m. ET)

ATMORE, Ala. (AP) — Larry Eugene Hutcherson was executed Thursday night by lethal injection for the 1992 killing of an 89-year-old Mobile woman who was nearly decapitated in her home.

Hutcherson apologized to the victim's family in a brief final statement and asked for forgiveness. "I'm so very sorry for hurting you like this. It's been a long time coming. If I could go back in time and change things, I most certainly would. I hope this gives you closure and someday find forgiveness for me."

A chaplain knelt beside the gurney and held Hutcherson's left hand and both prayed as he died. He was pronounced dead at 6:18 p.m. Hutcherson, 37, was executed for the killing of Irma Thelma Gray, who was assaulted and had her throat cut on June 26, 1992 as she confronted Hutcherson around midnight burglarizing her house.

"He's so guilty — very, very guilty," said Gray's daughter, Fran Sprott. "Our family is completely united in this execution. We've been ready for 14 years. He's had two trials," said Sprott, who lived about three miles from her mother, a native of Clarke County. Sprott, 69, who witnessed the execution with her sister, 73-year-old Thelma Pierce told reporters afterward there was no closure for her family. "The only person who got closure there in that room was him," Sprott said. "We have to live on with what he did for the rest of our lives."

The U.S. Supreme Court rejected Hutcherson's appeal Thursday afternoon. Hutcherson's attorney, Al Pennington of Mobile, said Hutcherson did not want to ask Gov. Bob Riley for clemency. Pennington said Hutcherson "didn't want to beg."

Prison officials said beginning at 9:30 a.m. Hutcherson met with 23 family members, including his ex-wife, Tracie Havens, and daughter Candace Hutcherson, who took home his letters, photos and three Bibles. Hutcherson had a breakfast of grits and eggs, but made no request for a final meal. He said he would eat from a vending machine with family members. He was described as very calm.

In his confession at his 1996 retrial, Hutcherson said he had taken six Valium tablets and had consumed a lot of whiskey at the Tarpon Lounge near the victim's home before committing the burglary and murder, according to the trial record. Gray's throat had been cut so severely that she was almost decapitated, according to trial testimony. Her body was lying on the kitchen floor. There was also evidence she had been sodomized. Hutcherson left his driver's license and other evidence at the crime scene. And he returned the next day to steal an air conditioner, microwave and more of Gray's belongings, according to his confession. He said he sold some and gave some away.

After the Alabama Supreme Court reversed Hutcherson's first conviction, he pleaded guilty to capital murder in 1996, and a Mobile County jury recommended the death penalty by an 11-1 vote. A judge adopted the jury's penalty. Hutcherson thanked the judge for the death sentence and his conviction became final on June 19, 1999.

About a dozen relatives of the victim headed for a Atmore motel to keep an execution vigil.

Alabama's last execution occurred Sept. 22, 2005, when John W. Peoples died by lethal injection at Holman Prison. There are currently 192 inmates on Alabama's death row.

"Killer asks forgiveness just before execution; Hutcherson slew woman, 89, in 1992," by Mike Cason (Friday, October 27, 2006)

ATMORE - Larry Eugene Hutcherson asked for forgiveness Thursday night just before the state of Alabama executed him for murdering an elderly Mobile woman 14 years ago. Hutcherson, 37, was pronounced dead from lethal injection at Holman Correctional Facility at 6:21 p.m. He had confessed to the June 26, 1992, murder of Irma Thelma Gray, 89. Under the influence of Valium and alcohol, he broke into her home, beat her and cut her throat so severely she was almost decapitated. "I just want to say I'm so very sorry for hurting you like this," Hutcherson said as he lay strapped to a gurney in the execution chamber. "I know this has been a long time coming. If I could go back in time and change it, I most certainly would. I hope this brings you closure and someday you can find forgiveness for me."

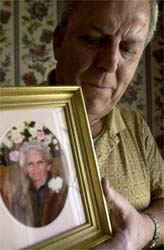

The victim's daughters, Francis Gray Sprott and Thelma Doris Gray Pierce of Mobile, watched the execution. Hutcherson did not look toward them when he made his final statement. "There was no closure for us," Sprott said after the execution. "The only person there that got closure was him. We have to live with what he did for the rest of our lives."

Sprott contrasted Hutcherson's manner of death with her mother's. "It was very soft," she said. "It was very white. It was very sterile. It was just as sweet as you would want to die. No pain, no nothing."

Strapped on his deathbed, Hutcherson stared quietly at the ceiling. When the chemicals begin to flow into both arms just after 6 p.m., he gave a thumbs-up sign to Holman chaplain Chris Summers. He then motioned Summers to his bedside, where Summers knelt for prayer. Hutcherson appeared to be praying aloud while Summers clasped his hands, but he fell silent about a minute later. By 6:10, he was still.

Hutcherson had appealed his case shortly before the execution was scheduled to occur, but his attorney, Al Pennington of Mobile, said he didn't claim he was innocent of the crime. "He admits he did it," Pennington said. "This is just a matter of whether there are mitigating issues that should have been raised." The U.S. Supreme Court decided Thursday afternoon that there were not, denying Hutcherson's request for a stay of execution. Hutcherson did not ask Gov. Bob Riley for clemency.

Hutcherson became the first Alabama inmate to be executed this year. He is the 11th to die by lethal injection since the state changed from the electric chair in 2002. About 20 relatives visited Hutcherson on Thursday, including his daughter, Candace Hutcherson; two sisters, Tanya Turner and Jacqueline Gaskey; and his ex-wife, Tracie Havens.

Hutcherson did not request a last meal. He and his family ate from vending machines in the prison's visitation yard. Pennington said Hutcherson seemed calm and content. "You wouldn't know that he stood to be executed at 6 o'clock tonight," Pennington said. His family did not witness his execution.

Hutcherson, who had been on Death Row for 13 years, left behind few belongings. He left his daughter three Bibles and assorted letters and pictures. He left a television set to one inmate and a radio and headphones to another.

Pennington said Hutcherson's request for a stay was mostly based on the contention that Alabama does not ensure an adequate defense for people charged with crimes that could lead to the death penalty. The state does not require that death penalty cases be handled according to American Bar Association standards, Pennington said. The standards include more training for lawyers who handle death penalty cases and other measures to ensure defendants are adequately represented, Pennington said.

"Judge dismisses Alabama inmate's bid to halt execution," by Garry Mitchell. (AP 10/18/2006, 12:23 p.m. ET)

MOBILE, Ala. (AP) — A federal judge has dismissed Alabama death row inmate Larry Eugene Hutcherson's bid to halt his execution set for next week in the 1992 killing of an elderly woman in her Mobile home. Hutcherson's complaint, which moved Wednesday to the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta, challenges Alabama's death penalty law, partly on grounds that it fails to require lawyers to be trained in the capital punishment law when representing capital murder defendants. State's attorneys said Hutcherson, who confessed to the crime and thanked the jury for the death sentence, was simply trying to delay the execution.

Without elaboration, U.S. District Judge William H. Steele dismissed Hutcherson's complaint Tuesday, granting a motion by state prosecutors who argued the court no longer had jurisdiction because the inmate had exhausted his appeals.

Hutcherson, 37, faces lethal injection at Holman Prison on Oct. 26 for the June 26, 1992, slaying of 89-year-old Irma Thelma Gray of Mobile. She was nearly decapitated in the attack, prosecutors said. According to the trial record, Hutcherson said he had taken six Valium tablets and consumed a lot of liquor before killing the woman. Prosecutors said he broke into Gray's home and beat and sodomized her along with cutting her throat. He left his driver license and other evidence at the crime scene.

"There is absolutely no public interest to be served by allowing a convicted murderer to re-litigate the exact claims that have already been dismissed by this court in a previous hearing," Assistant Attorney General James R. Houts said in a court filing Monday.

U.S. Chief District Judge Ginny Granade of Mobile on Dec. 8, 2005 dismissed Hutcherson's first petition, ruling Hutcherson had waited too late to file it. Then on March 17, the 11th Circuit denied Hutcherson's appeal. Houts said Hutcherson's conviction became final on June 19, 1999, and wasn't appealed in a timely manner. He said Hutcherson would need permission from the 11th Circuit to file a second petition at this point.

Hutcherson attorney Al Pennington on Oct. 12 asked for a federal court hearing and an order to block the execution, claiming Hutcherson was denied his constitutional rights to due process, equal protection and effective defense counsel. The complaint claims Alabama's death penalty statute "fails to assure that properly trained counsel will be provided to indigent defendants charged with capital offenses at all critical stages, including but not limited to, trial, appeal and post-conviction (collateral relief) in both state and federal court."

Houts responded that by providing appointed attorneys for discretionary appeals to the Alabama Supreme Court, the state already provides more assistance to inmates than required by the Constitution. In any case, he contends, that's not a reason to block the execution.

"Nowhere in his complaint does Hutcherson allege that he is actually innocent or that he was denied relief from a substantive error as a result of Alabama's post-conviction system," the state's motion says. It calls the inmate's complaint "theoretical in nature" and filed "solely in an attempt to delay execution of his lawful sentence."

After the Alabama Supreme Court reversed Hutcherson's first conviction, he pleaded guilty to capital murder in 1996 and a Mobile County jury recommended the death penalty by an 11-1 vote. Then-Circuit Judge Braxton Kittrell adopted the jury's decision, and Hutcherson thanked the judge for the penalty.

Alabama's last execution occurred Sept. 22, 2005 when John W. Peoples died by lethal injection at Holman Prison. There are currently 192 inmates on death row in Alabama.

On June 26, 1992, the body of 89-year-old Irma Thelma Gray was discovered in her home on Moffat Road in Mobile, Alabama. Shortly before dark, Larry Hutcherson broke into Irma's home while she was visiting a neighbor. He first tried to get in through the bathroom window and the front door, but could not, so he broke the front window and entered, cutting himself in the process.

Irma returned home while Hutcherson was ransacking her home. Hutcherson said that Irma ordered him out of the house and he refused. When Irma tried to leave herself, Hutcherson grabbed her and flung her to the floor. Hutcherson got a knife from the kitchen and stabbed her. Irma's throat had been cut so severely that she was almost decapitated. A forensic medical examiner testified that the cut on her throat was 10 inches long, beginning at her left earlobe and progressing to within one and one-half inch of her right earlobe. The cut severed her windpipe and her carotid artery and went all the way to her spine. Her nose was smashed and Irma had many other injuries that the medical examiner testified occurred before her throat was cut. These injuries, consistent with a beating, included numerous other cuts, bruises, and multiple fractured ribs. There was also evidence that Irma Gray had been sodomized.

An officer with the Mobile Police Department testified that when he arrived at the house to investigate Irma's death, the door to the screened porch was punched inward; a window had been broken and there was blood on the window sill, the furniture and the carpet. The inside of the house was in total disarray. The antenna for the television was on the floor and a bracket in a window sill, where an air conditioner would have been, was empty. Woodward found Irma's body lying face down on the kitchen floor. Blood covered the floor near her head and there was talcum powder on her lower body. There was also blood and a bloody footprint on the floor of the bathroom. The door to the garage was partially open and that one of the windowpanes in the door was broken and there was a trail of blood leading from the window to the driver's side of the automobile that was in the garage. Missing from the home were various appliances including a microwave oven, television and radio.

UPDATE: Before being given the lethal injection, Larry Hutcherson apologized to the family of Irma Gray saying he was "so very sorry for hurting you like this." He said he hoped someday they could forgive him. But Gray's daughter, Fran Sprott, said "He's so guilty -- very, very guilty" She said the family has been ready for Hutcherson's execution for 14 years.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Larry Hutcherson, October 26, AL

Do Not Execute Larry Hutcherson!

Larry Eugene Hutcherson, a 37-year-old white man, is scheduled to be executed by the State of Alabama on October 26, 2006. He was sentenced to death in 1993 for the murder of 89-year-old Irma Gray during a burglary. Hutcherson plead guilty and has since decided not to file a petition for clemency for the governor’s consideration.

It has been found in the last few years that at least seven Alabama death row prisoners, including Larry Hutcherson, have had to “navigate state post-conviction proceedings without the assistance of volunteer counsel”. In Hutcherson’s case, his counsel neglected to file pleadings within the limitations. With a legal system so flawed that defendants cannot rely upon counsel to adequately represent them, capital punishment should not be an option.

The State of Alabama has not yet executed an inmate in 2006. In fact, since resuming executions in 1983, Alabama has executed a relatively small number of people – sometimes going years without an execution. As such, it is difficult to ascertain the usefulness of capital punishment in Alabama as one would be hard pressed to demonstrate its deterrent effect.

Please write to Governor Bob Riley on behalf of Larry Hutcherson!

"Attorney targets death penalty law in bid to block execution," by Garry Mitchell. (Associated Press Posted on Thu, Oct. 12, 2006)

MOBILE, Ala. - An attorney for death row inmate Larry Hutcherson challenged Alabama's death penalty law Thursday in a federal complaint that seeks to block his scheduled Oct. 26 execution, a move that a prosecutor viewed as a delaying tactic. Hutcherson, 37, faces lethal injection at Holman Prison for the June 26, 1992, slaying of 89-year-old Irma Thelma Gray of Mobile. She was nearly decapitated in the attack in her home, according to prosecutors. In requesting an execution date, Attorney General Troy King said Hutcherson had exhausted his appeals and there are no stays of execution, nor any proceedings pending in any court.

In Thursday's complaint, defense attorney Al Pennington contends Hutcherson's civil rights were violated because lawyers at trial and during post-conviction proceedings "were not specifically trained in death penalty work nor does the state of Alabama require that counsel be so trained." In Montgomery, Assistant Attorney General James Houts said his office will review the complaint and respond. But he said it appeared to be "nothing more than a delaying tactic." He said Hutcherson's case has already gone through three levels of appeals and his death sentence has been upheld by the courts.

In his confession, Hutcherson said he had taken six Valium tablets and had drunk a lot of liquor before commiting the crime, according to the trial record. He left his driver license and other evidence at the crime scene. Prosecutors said Hutcherson broke into Gray's home and beat and sodomized her along with cutting her throat. Pennington asked for a federal court hearing and an order to block the execution, claiming Hutcherson was denied his constitutional rights to due process, equal protection and effective defense counsel.

The complaint claims Alabama's death penalty statute "fails to assure that properly trained counsel will be provided to indigent defendants charged with capital offenses at all critical stages, including but not limited to, trial, appeal and post-conviction (collateral relief) in both state and federal court." Payment for an attorney for Hutcherson on collateral relief was capped at $1,000 and counsel could not receive the aid of investigators or other necessary experts, Pennington wrote in his motion.

Pennington claims that once the Alabama Supreme Court has affirmed a death sentence on direct appeal, "there is no meaningful mechanism for seeking a getting a stay of the judgment pending a filing with the U.S. Supreme Court." The complaint names as defendants: Gov. Bob Riley, King, Lt. Gov. Lucy Baxley, Chief Justice Drayton Nabors and House Speaker Seth Hammett.

After the Alabama Supreme Court reversed Hutcherson's first conviction, he pleaded guilty to capital murder in 1996, and a Mobile County jury recommended the death penalty by an 11-1 vote. Then-Circuit Judge Braxton Kittrell adopted the jury's decision and sentenced Hutcherson to death. Hutherson thanked the judge for the penalty.

Alabama's last execution occurred Sept. 22, 2005 when John W. Peoples died by lethal injection at Holman Prison. There are currently 192 inmates on death row.

The following individuals have been executed by the State of Alabama at the Holman Correctional Facility near Atmore since 1943:

Inmate Date Method Victim

1 John Louis Evans 22 April 1983 electrocution Edward Nassar.

2 Arthur Lee Jones 21 March 1986 electrocution William Hosea Waymon.

3 Wayne Ritter 28 August 1987 electrocution Edward Nassar.

4 Michael Lindsey 26 May 1989 electrocution Rosemary Zimlich Rutland.

5 Horace Dunkins 14 July 1989 electrocution Lynn McCurry.

6 Herbert Richardson 18 August 1989 electrocution Rena Mae Callins.

7 Arthur Julius 17 November 1989 electrocution Susie Bell Sanders.

8 Wallace Thomas 13 July 1990 electrocution Quenette Shehane.

9 Larry Heath 30 March 1992 electrocution Rebecca Heam.

10 Cornelius Singleton 20 November 1992 electrocution Ann Hogan.

11 Willie Clisby 28 April 1995 electrocution Fletcher Handley.

12 Varnell Weeks 12 May 1995 electrocution Mark Batts.

13 Edward Horsley, Jr. 16 February 1996 electrocution Naomi Rolon.

14 Billy Wayne Waldrop 10 January 1997 electrocution Thurman Donahoo.

15 Walter Hill 2 May 1997 electrocution Willie Mae Hammock, John Tatum, and Lois Tatum.

16 Henry Hays 6 June 1997 electrocution Michael Donald.

17 Stephen Allen Thompson 8 May 1998 electrocution Robin Balarzs.

18 Brian K. Baldwin 18 June 1999 electrocution Naomi Rolon.

19 Victor Kennedy 6 August 1999 electrocution Annie Laura Orr.

20 David Ray Duren 7 January 2000 electrocution Kathleen Bedsole.

21 Freddie Lee Wright 3 March 2000 electrocution Warren Green and Lois Green.

22 Robert Lee Tarver, Jr. 14 April 2000 electrocution Hugh Sims Kite.

23 Pernell Ford 2 June 2002 electrocution Willie C. Griffith and Linda Gail Griffith.

24 Lynda Lyon Block 10 May 2002 electrocution Opelika police Sergeant Roger Lamar Motley.

25 Anthony Keith Johnson 12 December 2002 lethal injection Kenneth Cantrell.

26 Michael Eugene Thompson 13 March 2003 lethal injection Maisie Carlene Gray.

27 Gary Leon Brown 24 April 2003 lethal injection Jack David McGraw.

28 Tommy Jerry Fortenberry 7 August 2003 lethal injection Ronald Michael Guest, Wilbut T. Nelson, Robert William Payne, and Nancy Payne.

29 James Barney Hubbard August 5, 2004 lethal injection Lillian Montgomery.

30 David Kevin Hocker 30 September 2004 lethal injection Jerry Wayne Robinson.

31 Mario Giovanni Centobie 28 April 2005 lethal injection Moody police officer Keith Turner.

32 Jerry Paul Henderson 2 June 2005 lethal injection Jerry Haney in Talladega and for accepting $3,000 from Haney's wife for the killing.

33 George Everett Sibley, Jr.

(common-law husband of

Lynda Lyon Block) 4 August 2005 lethal injection Opelika police Sergeant Roger Lamar Motley.

34 John W. Peoples, Jr. September 22, 2005 lethal injection Paul Franklin, Judy Franklin, and Paul Franklin, Jr.

35 Larry Eugene Hutcherson October 26, 2006 lethal injection Irma Thelma Gray

Hutcherson v. State, 677 So.2d 1174 (Ala.Cr.App. 1994) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted in the Circuit Court, Mobile County, Braxton Kittrell, J., of capital murder occurring during course of sodomy and burglary, and was sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Taylor, J., held that: (1) indictment was not defective; (2) defendant was not denied fair trial when members of jury saw him in handcuffs and in prison uniform; (3) arresting officer had authority to arrest defendant on outstanding traffic warrant; (4) defendant knowingly waived his right to counsel; (5) prosecution's use of peremptory strikes to exclude women from jury was not Batson violation; (6) prosecutor did not improperly comment on defendant's postarrest silence; and (7) erroneous admission of DNA testimony was harmless. Affirmed. Judgment reversed, Ala., 677 So.2d 1205,on remand to, Ala.Cr.App., 677 So.2d 1210.

TAYLOR, Judge.

The appellant, Larry Eugene Hutcherson, was convicted of murder made capital because the murder occurred during the course of a sodomy and a burglary, violations of §§ 13A-5-40(a)(3) and 13A-5-40(a)(4), Code of Alabama 1975. The jury, by a vote of 11 to 1, recommended the death penalty be imposed. The trial court accepted the jury's recommendation and sentenced the appellant to death by electrocution.

The state's evidence tended to show that on June 26, 1992, the body of 89-year-old Irma Thelma Gray was discovered in her home on Moffat Road in Mobile, Alabama. The victim's throat had been cut so severely that she was almost decapitated. Dr. Leroy Riddick, a forensic medical examiner, testified that the cut on her throat was 10 inches long, beginning at her left earlobe and progressing to within one and one-half inch of her right earlobe. The cut severed her windpipe and her carotid artery and went all the way to her spine. The victim had many other injuries that Dr. Riddick testified occurred before her throat was cut. These injuries, consistent with a beating, included numerous other cuts, bruises, and multiple fractured ribs. There was also evidence that the victim had been sodomized. Lieutenant Frank Woodward of the Mobile Police Department testified that when he arrived at the house to investigate Ms. Gray's death, the door to the screened porch was punched inward; a window had been broken and there was pieces of broken glass and blood on the window sill. The inside of the house was in total disarray. The antenna for the television was on the floor and a bracket in a window sill, where an air conditioner would have been, was empty. Woodward found Mrs. Gray's body lying face down on the kitchen floor. Blood covered the floor near her head and there was talcum powder on her lower body. There was also blood and a bloody footprint on the floor of the bathroom. Woodward also stated that the door to the garage was partially open and that one of the windowpanes in the door was broken and there was a trail of blood leading from the window to the driver's side of the automobile that was in the garage. Officer Lamar Whitten of the Mobile Police Department stated that he searched the house and found the appellant's driver's license in front of a closet in one of the bedrooms. Near the appellant's driver's license was a bloody knife.

A fingerprint was also discovered on the washing machine. The print matched the print of the appellant's right thumb. Sarah Scott of the state forensic department testified that she was called to the scene to retrieve blood samples from certain areas in the house. A rag found in the garage was covered in blood consistent with the appellant's blood type. The blood on the garage window sill was also consistent with the appellant's blood as were the bloodstains lifted from the front porch. She also testified that bloodstains on a pair of jeans that the appellant was wearing when he was arrested were consistent with the victim's blood type.

The appellant's mother, Deborah Hutcherson, testified that around 6:00 a.m. on a morning during the last week of June 1992 she received a telephone call from her son asking her to pick him up on Moffat Road. The appellant told his mother that he had been in a fight and that his arm had been cut. She found her son at the Overlook Shopping Center, not far from the victim's house. She said that the cut on his arm was bad and that it looked like he needed stitches. She also stated that the appellant did not appear to be drunk but that he looked “real tired.”

Sergeant Lester Clark testified that on June 27, 1992, he took the appellant into custody on a traffic attachment out of Prichard. He said that when he found the appellant he was asleep in his car outside the Tarpon Lounge, which was located about one-half mile from the victim's house. Clark took the appellant to the police station where he read the appellant his Miranda FN1 rights. Initially, the appellant stated that he did not wish to make a statement. About 45 minutes later, the appellant asked to speak with Clark. Sergeant Clark transcribed the following statement as he was talking with the appellant: FN1. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16 L.Ed.2d 694 (1966).

“ ‘[I] want to tell you about the murder.’ I again advised him that he did not have to say anything, but he stated that he had to tell someone and he wanted it to be me. The suspect continued to talk stating that, ‘I killed her.’ He stated, ‘I went to the house on Wednesday night, or it could have been early Thursday morning. Might have been after twelve o'clock. I had just left the Tarpon [Lounge] and was looking for a house to break in as I walked west on Moffat Road. I picked that house because there were no cars in the driveway and it was dark. I went in the bathroom window.’ And he said, ‘That is not-’ he hesitated and he said, ‘That is not too clear because I had taken five Valiums and drank a lot of whiskey. I knew that I knocked out-I knew that I knocked the pane out of the window to get in. I remember I cut my arm when I broke out the garage window.' “ ‘I had been in the house for awhile before I saw the old lady, who just showed up in the kitchen. I asked her where her money was and the jewelry. She wouldn't tell me and I began-she began to try to get out of the back door. I kept pulling her back, and I cut her throat. I took off her panties and poured powder over her which I found in the bathroom.

“ ‘I tried to get the car started, but it wouldn't. I left and called my mamma to pick me up. She picked me up on Moffat. I went back into the house Thursday night. I had passed several times during the day and saw that no one had found her. I went through parts of the house that I did not go through Wednesday night. This is when I took out the air conditioner and the rest of the stuff, and put it next to the fence. “ ‘I got Hardy [Avera] to stop after leaving the Tarpon Friday morning and pick up the stuff. Most of the stuff might have been-might have left town by now. I sold some and I just almost gave some away to people I owed. The air conditioner I know is still here. I know where it is. It is at my stepfather's house, Jackie Lang. “ ‘The microwave, I know where it is, but she is related to my wife, and I wouldn't want to get her involved, but I know it is there. Now, I feel better. I've told you.’ ”

Three witnesses testified that the appellant sold them a microwave, a television, and a radio, respectively, in the last week of June 1992. These items were identified by the victim's son-in-law as having belonged to the victim. Hardy Avera testified that on Wednesday in the last week of June 1992 the appellant came to his house wearing jeans and black tennis shoes. The appellant told him that “he thought he had killed someone.” The next day he saw the appellant at the Tarpon Lounge and he took him to the victim's house. He said that the appellant went inside and came back with an air conditioner and some other items. The appellant's stepsister, was present when her father, Jackie Lang, received a telephone call from the appellant. She said that during the conversation her father wrote down on a piece of paper that Larry had killed an old lady. Ms. Lang also stated that she testified before the grand jury that the appellant had told her that “he would rather die in the electric chair than live with what he had done to the victim.”

Many of the issues raised by the appellant on appeal were not first presented to the trial court. However, because this case involves the death penalty, this court is obliged, under Rule 45A, A.R.App.P., to apply the plain error doctrine. Rule 45A, A.R.App.P., states: “In all cases in which the death penalty has been imposed, the court of criminal appeal shall notice any plain error or defect in the proceedings under review, whether or not brought to the attention of the trial court, and take appropriate appellate action by reason thereof, whenever such error has or probably has adversely affected the substantial right of the appellant.”

As this court stated in Haney v. State, 603 So.2d 368 (Ala.Cr.App.1991), aff'd, 603 So.2d 412 (Ala.1992), cert. denied, 507 U.S. 925, 113 S.Ct. 1297, 122 L.Ed.2d 687 (1993): “The Alabama Supreme Court has adopted federal case law defining plain error, holding that ‘ “[p]lain error” only arises if the error is so obvious that the failure to notice it would seriously affect the fairness or integrity of the judicial proceedings,’ Ex parte Womack, 435 So.2d 766, 769 (Ala.), cert. denied, 464 U.S. 986, 104 S.Ct. 436, 78 L.Ed.2d 367 (1983) (quoting United States v. Chaney, 662 F.2d 1148, 1152 (5th Cir.1981)).” “[T]he plain-error exception to the contemporaneous-objection rule is to be ‘used sparingly, solely in those circumstances in which a miscarriage of justice would otherwise result.’ ” United States v. Young, 470 U.S. 1, 15, 105 S.Ct. 1038, 1046, 84 L.Ed.2d 1, 14 (1985), quoting United States v. Frady, 456 U.S. 152, 163, 102 S.Ct. 1584, 1592, 71 L.Ed.2d 816 (1982). To find plain error “the claimed error [must] not only [have] seriously affected [the defendant's] ‘substantial rights,’ but ··· it [must have] had an unfair prejudicial impact on the jury's deliberations.” Young, 470 U.S. at 18, 105 S.Ct. at 1047, n. 14, 84 L.Ed.2d at 14.

* * *

The appellant next contends that the DNA testimony regarding the semen sample recovered from the victim, which linked the appellant to the act of sodomy, should not have been received into evidence because, he says, the prosecutor failed to satisfy the test articulated by the Alabama Supreme Court in Ex parte Perry, 586 So.2d 242 (Ala.1991). The following three-pronged test must be met before DNA test results may be received into evidence.

“I. Is there a theory, generally accepted in the scientific community, that supports the conclusion that DNA forensic testing can produce reliable results? “II. Are there current techniques that are capable of producing reliable results in DNA identification and that are generally accepted in the scientific community? “III. In this particular case, did the testing laboratory perform generally accepted scientific techniques without error in the performance or interpretation of the tests?” Perry, 586 So.2d at 253. “Prior to the admission of DNA testimony into evidence, a hearing outside the presence of the jury must be held to determine if the test has been met.” Yelder v. State, 630 So.2d 92, 102 (Ala.Cr.App.1991), rev'd on other grounds, 630 So.2d 107 (Ala.1992). In this case, no hearing was held outside the presence of the jury. Further, there was no testimony that satisfied the complete Perry test. We have recognized that DNA testing is generally accepted in the scientific community. See Seritt v. State, 647 So.2d 1 (Ala.Cr.App.1994); Yelder. However, there was not sufficient evidence presented in this case that the test performed in this case was reliable. The prosecution here failed to satisfy the third prong of the Perry test.

Thus, the court should have not allowed the DNA testimony to be received into evidence. However, our inquiry does not end here. Though this state has not had occasion to apply the harmless error analysis to the unlawful admission of DNA testimony, other states have applied the harmless error doctrine in this context. State v. Bible, 175 Ariz. 549, 858 P.2d 1152 (1993), cert. denied, 511 U.S. 1046, 114 S.Ct. 1578, 128 L.Ed.2d 221 (1994); People v. Wallace, 14 Cal.App. 4th 651, 17 Cal.Rptr.2d 721 (1993); People v. Barney, 8 Cal.App. 4th 798, 10 Cal.Rptr.2d 731 (1992); State v. Nielsen, 467 N.W.2d 615, 619 (Minn.1991). Cf. People v. Finley, 161 Mich.App. 1, 410 N.W.2d 282 (1987), aff'd, 431 Mich. 506, 431 N.W.2d 19 (1988) (unlawful admission of blood typing was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt); People v. Proveaux, 157 Mich.App. 357, 403 N.W.2d 135 (1987) (unlawful admission of analysis of semen stain was harmless, given the overwhelming evidence of the appellant's guilt).

As the Arizona Supreme Court stated in Bible: “When an issue is raised but erroneously ruled on by the trial court, this court reviews for harmless error. See State v. McVay, 127 Ariz. 450, 453, 622 P.2d 9, 12 (1980). Absent ‘structural defect,’ Arizona v. Fulminante, 499 U.S. 279, 309[-310], 111 S.Ct. 1246, 1265, 113 L.Ed.2d 302 (1991), and other matters not subject to harmless error analysis, we use one test to determine whether error is harmless in criminal cases, State v. White, 168 Ariz. 500, 508, 815 P.2d 869, 877 (1991), cert. denied, 502 U.S. 1105, 112 S.Ct. 1199, 117 L.Ed.2d 439 (1992); State v. Lundstrom, 161 Ariz. 141, 150 n. 11, 776 P.2d 1067, 1076 n. 11 (1989); State v. Thomas, 133 Ariz. 533, 538, 652 P.2d 1380, 1385 (1982). Error, be it constitutional or otherwise, is harmless if we can say, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the error did not contribute to or affect the verdict. Lundstrom, 161 Ariz. at 150 & n. 11, 776 P.2d at 1076 & n. 11. ‘The inquiry ··· is not whether, in a trial that occurred without the error, a guilty verdict would surely have been rendered, but whether the guilty verdict actually rendered in this trial was surely unattributable to the error.’ Sullivan v. Louisiana, 508 U.S. 275, 279, 113 S.Ct. 2078, 2081, 124 L.Ed.2d 182 (1993); accord McVay, 127 Ariz. at 453, 622 P.2d at 12. We must be confident beyond a reasonable doubt that the error had no influence on the jury's judgment. “There is no bright line statement of what is and what is not harmless error. See Bush v. State, 19 Ariz. 195, 204, 168 P. 508, 512 (1917); see also Jack B. Weinstein & Margaret A. Berger, 1 Weinstein's Evidence, § 103[06], at 103-70 to 81 (1992) (listing factors courts examine in determining whether error was harmless)····” “···· “··· [T]he properly admitted evidence in this case goes far beyond overwhelming evidence of guilt. It is not only inconsistent with any reasonable hypothesis of innocence, it refutes any hypothesis other than Defendant's guilt····”

“Given this unequivocal evidence, independent of the hotly contested DNA probability evidence, we find beyond a reasonable doubt that the erroneous admission of the DNA evidence could have had ‘no influence on the verdict of [this] jury’ McVay, 127 Ariz. at 453, 622 P.2d at 12. Other courts have reached similar conclusions with weaker, or at least comparably strong, evidence of guilt independent of the erroneous admission of DNA evidence. See, e.g., [ People v.] Barney, 10 Cal.Rptr.2d [731] at 747-48 [ (1992) ] (upholding conviction where defendant's wallet found on bloodstained couch in victim's home, defendant's fingerprint found in room of victim's home, and non-DNA blood testing linked defendant to crime scene); State v. Nielsen, 467 N.W.2d 615, 619 (Minn.1991) (victim last seen alive with defendant, blood matching victim's found on defendant's shirt, untypable human blood found in defendant's car, defendant's blood type matched semen found on victim's body, defendant had black eye day after murder, and defendant left the area when told that the police were looking for him); cf. [People v.] Wallace, 17 Cal.Rptr.2d [721] at 726-27 [ (1993) ] (following Barney and upholding conviction where crimes were distinctive, one victim identified defendant, circumstantial evidence connected defendant to crimes, traditional blood typing eliminated all but two or three percent of the population, and defendant admitted committing offenses to fiancee); [People v.] Atoigue, 1992 WL 245628, at 4 [D.Guam App.Div., September 1, 1992] (upholding conviction where victim identified defendant).” Bible, 858 P.2d at 1191-93.

We realize that the courts in this state have stated that “overwhelming evidence of guilt does not render prejudicial error harmless under Rule 45, A.R.App.P.” Tomlin v. State, 591 So.2d 550 (Ala.Cr.App.1991); Malone v. City of Silverhill, 575 So.2d 107 (Ala.1990); Hall v. State, 520 So.2d 218 (Ala.Cr.App.1987); Carroll v. State, 599 So.2d 1253 (Ala.Cr.App.1992), aff'd, 627 So.2d 874 (Ala.1993), cert. denied, 510 U.S. 1171, 114 S.Ct. 1207, 127 L.Ed.2d 554 (1994). However, the Alabama Supreme Court in Ex parte Greathouse, 624 So.2d 208, 211 (Ala.1993), stated: “As the Court of Criminal Appeals recognized, this Court has held that ‘ “[o]verwhelming evidence of guilt does not render prejudicial error harmless under Rule 45, Ala.R.App.P.” ’ Ex parte Malone, 575 So.2d 106, 107 (Ala.1990) (quoting Ex parte Lowe, 514 So.2d 1049, 1050 (Ala.1987)); see also Ex parte Johnson, 507 So.2d 1351, 1356 (Ala.1986). In Malone, this Court held that the admission of evidence of scientific test results without the laying of a proper predicate was not harmless. In that case, this Court discussed why the jury's consideration of the test results could have affected its determination on the issue of guilt. This Court specifically held that the improper admission of the evidence of the test results might have adversely affected the defendant's right to a fair trial and, therefore, that the admission of that evidence required a reversal of his conviction. In this case, the Court of Criminal Appeals determined, based upon its review of the record, that the comment by the codefendant's counsel did not have such an adverse effect and that ‘the evidence of [the defendant's] guilt was “virtually ironclad.” ’ 624 So.2d at 209.

“In Wilson, this Court, quoting Chapman v. California], 386 U.S. [18] 24, 87 S.Ct. [824] 828, [17 L.Ed.2d 705 (1967) ] stated that ‘ “ before a federal constitutional error can be held harmless, the court must be able to declare a belief that it was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.” ’ 571 So.2d at 1264. Applying that rule of law to the facts of this case, we conclude, as did the Court of Criminal Appeals, that the record shows that the evidence of guilt is ‘virtually ironclad’; therefore, we agree with the Court of Criminal Appeals that the comment did not affect the outcome of the trial or otherwise prejudice Greathouse's right to a fair trial.” (Emphasis added.) We hold that the admission of the DNA evidence was “harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.” There was absolutely no doubt that the victim had been sodomized. Dr. Riddick testified that semen was found in the victim's rectum. Here, no other reasonable inference could have been drawn from the evidence except that the appellant sodomized the victim. The evidence against the appellant was “virtually ironclad.” Greathouse. For this reason, we hold that the unlawful admission of the DNA testimony amounted to harmless error. The appellant also raises several other issues concerning the admission of the DNA evidence. Having found that the court erred in receiving this testimony into evidence we find it unnecessary to address these issues. The admission of the DNA evidence, although error, was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.

* * *

The appellant next argues that there was insufficient evidence to show that he committed the murder during the course of committing a sodomy. Specifically, he argues that there was evidence that the victim was dead at the time she was sodomized and that there was no evidence that the appellant formed the intent to sodomize the victim before the victim was killed. Dr. Leroy Riddick, a forensic pathologist, testified that semen was found in the victim's rectum but that there was no evidence of trauma to the rectum. He testified that this could be either because of her age and the loss of elasticity in the area or because she was sodomized after her death. The appellant argues that on the basis of Dr. Riddick's testimony he could not be found guilty of sodomizing the victim and therefore could not be found guilty of the capital offense of murder committed during the course of sodomy under § 13A-5-40(a)(3), Code of Alabama 1975. We hold that the legislature did not intend such a result when it enacted § 13A-5-40(a)(3).

Section 13A-5-40(a)(3) defines a capital murder as “murder by the defendant during a rape in the first or second degree or an attempt thereof committed by the defendant; or murder by the defendant during sodomy in the first or second degree or an attempt thereof committed by the defendant.” (Emphasis added.) “During” is defined in § 13A-5-39(2) as “in the course of or in connection with the commission of, or in immediate flight from the commission of the underlying felony or attempt thereof.” This court in Hallford v. State, 548 So.2d 526 (Ala.Cr.App.1988), aff'd 548 So.2d 547 (Ala.1989), cert. denied, 493 U.S. 945, 110 S.Ct. 354, 107 L.Ed.2d 342 (1989), had occasion to determine whether a robbery that occurred after a murder could support a conviction for capital murder. Judge Patterson, writing for the court, stated: “The capital crime of robbery when the victim is intentionally killed is a single offense beginning with the act of robbing or attempting to rob and culminating in the act of intentionally killing the victim; the offense consists of two elements, robbing and intentional killing···· The intentional murder must occur during the course of a robbery in question; however, the taking of the property of the victim need not occur prior to the killing···· While the violence or intimidation must precede or be concomitant with the taking, it is immaterial that the victim is dead when the theft occurs.” 548 So.2d at 534 (citations omitted).

The reasoning of Hallford applies to this case. It makes no difference if the actual act of sodomy occurred after the victim's death. We agree with the Minnesota Supreme Court: “One who ‘[c]auses the death of a human being while committing or attempting to commit criminal sexual conduct in the first or second degree with force or violence, either upon or affecting the person or another,’ is guilty of murder in the first degree. Minn.Stat. § 609.185(2) (1990). In Minnesota the felony-murder rule applies whenever the felony and the homicide ‘are part of one continuous transaction.’ Bellcourt v. State, 390 N.W.2d 269, 274 (Minn.1986) [quoting Kochevar v. State, 281 N.W.2d 680, 686-87 n. 4 (Minn.1979) ]. Thus, the felony-murder rule applies even though the underlying felony is completed after the homicide, provided the felony and homicide are parts of a single ‘continuous transaction.’ Compare State v. LaTourelle, 343 N.W.2d 277 (Minn.1984) (defendant convicted of first degree felony-murder where defendant intended to rape victim prior to the homicide but the rape took place after the homicide) with State v. Givens, 332 N.W.2d 187 (Minn.1983) (defendant acquitted of first degree felony-murder where defendant participated in murder of victim, then returned to murder scene a short time later to rape victim).

“The defendant correctly points out the absence of scientific evidence that the sexual assault took place while the victim was alive: the autopsy did not reveal whether penetration occurred before or after [the victim's] death. Nevertheless, there was a great deal of evidence from which the jury could conclude that death occurred during or as the result of a sexual assault. Many of the victim's wounds, the disarray of her clothing, and the way in which the clothing had been torn from her upper body were suggestive of, or at least consistent with, a sexually motivated assault. The jury was not required to believe defendant's tale of bestiality-that the thought of sexual activity did not occur to him until after he had driven around for a half hour in a vain search for a policeman to whom he could turn over [the victim's] dead body. Even if the rape occurred after death, the jury could have believed that the assault was sexually motivated and that the criminal sexual conduct and the homicide were one continuous transaction making the crime first degree felony murder. State v. Nielsen, 467 N.W.2d 615, 618 (Minn.1991). (Emphasis added.) There was sufficient evidence for the jury to conclude that the murder occurred “during” the sodomy as defined in Ex parte Johnson, 620 So.2d 709 (Ala.1993).

* * *

The appellant next contends that the trial court's findings were erroneous. Initially, he argues that the court erred in finding that the crime was “especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel.” Previously, we quoted the court's order regarding this aggravating circumstance. The court's order clearly reflects that no error occurred in its finding the circumstances surrounding the murder to be “especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel.” Ex parte Kyzer, 399 So.2d 330 (Ala.1981); Henderson v. State, 583 So.2d 276, 304 (Ala.Cr.App.1990), aff'd, 583 So.2d 305 (Ala.1991), cert. denied, 503 U.S. 908, 112 S.Ct. 1268, 117 L.Ed.2d 496 (1992). The appellant further contends that § 13A-5-49(8) is unconstitutional on its face. This aggravating circumstance has been upheld. Hallford, supra. The appellant last contends that the court erred in failing to find his alleged intoxication at the time of the offense and his reputation in the community as mitigating circumstances. As this court recently stated in Dobyne: “ ‘The sentencing tribunal, and, on appeal, the reviewing court, determines the weight to be assigned to each factor. Ex parte Hart, 612 So.2d 536 (Ala.1992), cert. denied, Hart v. Alabama, 508 U.S. 953, 113 S.Ct. 2450, 124 L.Ed.2d 666 (1993); Smith v. State, 407 So.2d 894 (Fla.1981), cert. denied, 456 U.S. 984, 102 S.Ct. 2260, 72 L.Ed.2d 864 (1982).’ ” 672 So.2d at 1351, quoting Ex parte Giles, 632 So.2d 577, 585 (Ala.Cr.App.1993). The court's finding concerning the absence of these mitigating factors is supported by the evidence at trial.

Section 13A-5-53, Code of Alabama 1975, requires this court to address the propriety of the appellant's conviction and sentence to death. The appellant was indicted and convicted of capital murder as defined in § 13A-5-40(a)(3) and § 13A-5-40(a)(4), i.e., murder committed during the course of a burglary and during the course of sodomy. The record reflects that the appellant's sentence was not imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor. § 13A-5-53(b)(1), Code of Alabama 1975.

A review of the record shows that the trial court correctly found that the aggravating circumstances outweighed the mitigating circumstances. The trial court reviewed all the evidence offered in mitigation and found as statutory mitigating circumstances that the appellant had no significant history of prior criminal activity, § 13A-5-51(1), and that the appellant was 22 years old at the time of the murder, § 13A-5-51(7). The court found as a nonstatutory mitigating circumstance that: “As a result of multiple relationship with other men and numerous marriages, [the appellant's mother] did not provide a nurturing, caring environment. The Court further finds that the death of the defendant's adoptive father affected the defendant, and the defendant's attempted suicide suggest a degree of depression at those points in his life.”

The court found as aggravating circumstances that the offense was committed during the course of a burglary, § 13A-5-49(4), and that the crime was “especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel” compared to other capital crimes § 13A-5-49(8). The court weighed the mitigating and the aggravating circumstances and sentenced the appellant to death. We agree with the court's findings in the present case. However, pursuant to § 13A-5-53(b)(2), this court must independently weigh the aggravating and the mitigating circumstances to determine the propriety of the appellant's death sentence. After an independent weighing, this court is convinced that the appellant's sentence to death by electrocution is the appropriate sentence. As § 13A-5-53(b)(3) provides, we must also address whether the appellant's sentence was disproportionate or excessive when compared to the penalties imposed in similar cases. The appellant's sentence was neither. Hunt, supra. Last, we have searched the entire record for any error that may have adversely affected the appellant's substantial rights and have found none. Rule 45A, A.R.App.P.

The appellant's conviction and sentence to death are due to be, and are hereby, affirmed. AFFIRMED. All the Judges concur.

Ex parte Hutcherson, 677 So.2d 1205(Ala. 1996).

Defendant was convicted of capital murder following jury trial by the Circuit Court, Mobile County, No. CC-92-2955, Braxton Kittrell, J. Conviction and death sentence were affirmed by the Court of Criminal Appeals, 677 So.2d 1174, and petition for certiorari review was granted. The Supreme Court, Kennedy, J., held that: (1) admitting deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) evidence, without laying foundation indicating that testing laboratory performed generally accepted techniques without error, was prejudicial, and (2) admitting DNA evidence without proper foundation can never be harmless error. Reversed and remanded. Butts, J., dissented and filed opinion in which Maddox, J., joined. On remand to, Ala.Cr.App., 677 So.2d 1210.

Hutcherson v. State, 727 So.2d 846 (Ala.Cr.App. 1997) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death. On appeal, the Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed, 677 So.2d 1174, but the Supreme Court reversed, 677 So.2d 1205, and the Court of Criminal Appeals remanded to trial court for further proceedings, 677 So.2d 1210. On remand, defendant entered plea of guilty before the Mobile Circuit Court, No. CC-92-2955.80, Braxton Kittrell, J., to capital murder, and, upon recommendation of jury, was again sentenced to death. Defendant appealed. The Court of Criminal Appeals, Baschab, J., held that: (1) evidence was sufficient to prove that defendant had specific intent to kill victim; (2) evidence was sufficient to permit submission of defendant's guilt to jury upon his plea of guilty; (3) defendant was not entitled to have jury instructed on lesser-included offenses; (4) prosecutor's comments during closing argument of penalty phase were not misconduct; (5) trial court's striking of three white jurors for purpose of replacing them with three black jurors it determined to have been improperly stricken by state was not plain error; (6) evidence justified trial court's finding of “especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel” aggravating circumstance; (7) photographs of victim's body were relevant and admissible; and (8) trial court's findings with respect to aggravating and mitigating circumstances and its imposition of death penalty were supported by record, and sentence was neither disproportionate nor excessive compared to penalties imposed in similar cases. Affirmed, Ala., 727 So.2d 861.

Hutcherson v. Riley, --- F.3d ----, 2006 WL 3008401 (11th Circuit 2006) (Sec. 1983).

Background: Following affirmance of his murder conviction and death sentence, 727 So.2d 846, and denial of habeas relief, prisoner filed § 1983 action alleging that Alabama's failure to adopt American Bar Association's guidelines for counsel in death penalty cases as binding constituted a denial of his right to counsel and due process. The United States District Court for the Southern District of Alabama, 06-00657-CV-WS-C, William H. Steele, J., 2006 WL 2989214, dismissed the complaint and prisoner appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals, Dubina, Circuit Judge, held that:

(1) prisoner's § 1983 claim constituted the “functional equivalent” of a second habeas petition, and

(2) prisoner was not entitled to an equitable stay of his execution.

Affirmed, and motion to stay execution denied.

DUBINA, Circuit Judge:

Before the court for review is Larry Eugene Hutcherson's (“Hutcherson”) appeal from the district court's dismissal of his 42 U.S.C. § 1983 action, and a Motion to Stay his Execution pending appeal (Appeal No. 06-15510). Hutcherson filed his § 1983 complaint in district court 14 days prior to his scheduled execution date of October 26, 2006. On October 19, 2006, Hutcherson filed an Application for Leave to File a Successive Habeas Petition and a Motion to Stay (Appeal No. 06-15544), which we deny in a separate order. For the reasons that follow, we affirm the district court's order denying Hutcherson relief under § 1983, and we deny his concomitant Motion to Stay his Execution.

I. BACKGROUND

A Mobile County, Alabama, jury originally convicted Hutcherson of capital murder occurring during the course of sodomy and burglary. The jury recommended a death sentence by a vote of 11-1. The circuit court followed the jury's recommendation and sentenced Hutcherson to death. In affirming Hutcherson's convictions and sentence, the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals found the facts, in part, as follows:

The state's evidence tended to show that on June 26, 1992, the body of 89-year-old Irma Thelma Gray was discovered in her home on Moffatt Road in Mobile, Alabama. The victim's throat had been cut so severely that she was almost decapitated. Dr. Leroy Riddick, a forensic medical examiner, testified that the cut on her throat was 10 inches long, beginning at her left earlobe and progressing to within one and one-half inch of her right earlobe. The cut severed her windpipe and her carotid artery and went all the way to her spine. The victim had many other injuries that Dr. Riddick testified occurred before her throat was cut. These injuries, consistent with a beating, included numerous other cuts, bruises, and multiple fractured ribs. There was also evidence that the victim had been sodomized. Hutcherson v. State, 677 So.2d 1174, 1178 (Ala.Crim.App.1994).

The Alabama Supreme Court reversed and remanded, holding that the admission of DNA evidence, without laying a proper foundation indicating that the testing laboratory performed generally accepted techniques, was error. Ex parte Hutcherson, 677 So.2d 1205 (Ala.1996). Upon remand, Hutcherson entered a plea of guilty to capital murder, and, upon recommendation of the jury, the circuit court again sentenced him to death. The appellate court affirmed. Hutcherson v. State, 727 So.2d 846 (Ala.Crim.App.1997). The Alabama Supreme Court affirmed, Ex parte Hutcherson, 727 So.2d 861 (Ala.1998), and the United States Supreme Court denied certiorari review. Hutcherson v. Alabama, 527 U.S. 1024, 119 S.Ct. 2371, 144 L.Ed.2d 775 (1999).

Subsequently, Hutcherson filed a post-conviction petition pursuant to Rule 32, Ala. R.Crim. P. in the circuit court. The State filed a petition for writ of mandamus, directing the Alabama Supreme Court to order the circuit court to dismiss Hutcherson's petition on jurisdictional grounds. The Alabama Supreme Court granted the mandamus petition. Ex parte Hutcherson, 847 So.2d 386 (Ala.2002). The circuit court denied the Rule 32 petition as untimely, and that adjudication was affirmed by both levels of Alabama appellate courts. See Hutcherson v. State, 886 So.2d 181 (Ala.Crim.App.2003); Ex parte Hutcherson, 887 So.2d 212 (Ala.2004). Hutcherson filed a successive Rule 32 petition, arguing that the Alabama Death Penalty System is infirm because there is no provision for automatic appointment of counsel after direct appeals are exhausted, and because there is no provision for formal training of counsel in the intricacies of collateral proceedings in the state and federal systems. The circuit court dismissed this Rule 32 petition as time-barred and otherwise lacking merit. Hutcherson, who was represented by counsel in each of these Rule 32 proceedings, did not appeal.

Shortly before he filed his successive Rule 32 petition, Hutcherson filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus in federal district court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2254. The claims Hutcherson raised in his federal habeas petition almost mirrored the claims raised in his second Rule 32 petition. In particular, Hutcherson contended that the Alabama Death Penalty Statute was unconstitutional because it did not provide for appointment of counsel for Rule 32 proceedings, did not train counsel in matters of federal collateral relief, and did not make sufficient funds available for retention of forensic, psychiatric and mitigation experts in post-conviction proceedings. On December 8, 2005, the district court entered an order dismissing Hutcherson's 28 U.S.C. § 2254 petition as untimely because the petition had not been filed within the one-year limitations period provided by the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (“AEDPA”), 28 U.S.C. § 2244(d)(1), and finding that Hutcherson had failed to make any showing that might warrant equitable tolling. On appeal, this court denied Hutcherson's request for a Certificate of Appealability (“COA”). Hutcherson sought no further appellate review.

On June 27, 2006, defendant Attorney General Troy King filed a Motion to Set an Execution Date in the Alabama Supreme Court. The State served Hutcherson and his present counsel with notice of this motion. Hutcherson did not file any legal action or challenge to the State's motion. Attorney General King renewed his request for the setting of an execution date, as the court had taken no action in response to his earlier request. On September 25, 2006, the Alabama Supreme Court responded to the State's request and set October 26, 2006, as the date for Hutcherson's execution. After having knowledge of the State's request of an execution date for over three months, Hutcherson, 14 days before his scheduled execution, filed a complaint in the federal district court pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983 seeking injunctive relief. This action raised no new claims for relief, but instead, reiterated Hutcherson's arguments from his failed, untimely § 2254 petition and his successive Rule 32 petition. In particular, Hutcherson asserted that the Alabama Death Penalty Statute is constitutionally deficient in the following respects: “it fails to assure that properly trained counsel will be provided to indigent defendants” at trial, appellate and post-conviction stages; it fails to provide Hutcherson with representation as a matter of right in his Rule 32 actions; it caps compensation for Hutcherson's Rule 32 counsel at $1,000, and there is no provision for hiring experts or investigators; certain “esoteric peculiarities” in the Alabama post-conviction system create traps for unwary, untrained counsel; after a death sentence is affirmed on direct appeal, “it provides no meaningful mechanism for seeking ··· a stay of the judgment pending a filing with the United States Supreme Court;” it does not toll the time for filing a Rule 32 petition during the time in which a petition for writ of certiorari could have been filed with the United States Supreme Court, leading to “confusion” in the filing of a Rule 32 petition; and it does not meet the minimum standards articulated in Wiggins v. Smith, 539 U.S. 510, 123 S.Ct. 2527, 156 L.Ed.2d 471 (2003). Based on these allegations, Hutcherson requested the district court find that his constitutional rights had been violated, strike down the Alabama Death Penalty Statute as unconstitutional, enjoin his execution, and enjoin the State from proceeding against Hutcherson pending appointment of Wiggins-compliant counsel.

The district court found that Hutcherson's complaint, unlike the petitioners complaints in Hill v. McDonough, --- U.S. ----, 126 S.Ct. 2096, 165 L.Ed.2d 44 (2006), and Nelson v. Campbell, 541 U.S. 637, 124 S.Ct. 2117, 158 L.Ed.2d 924 (2004), did not challenge a specific method of execution, nor pose claims that could reasonably be characterized as an attack on the conditions of his confinement. Instead, the district court found that Hutcherson's complaint was a broad-based attack on the structure and safeguards of the Alabama Death Penalty System. The district court found that this argument, if successful, would tend to undermine the validity of Hutcherson's conviction and sentence, rather than the conditions of confinement or the specific manner of his execution. Accordingly, the district court determined that Hutcherson's complaint falls squarely within the core of habeas corpus and, as such, is not cognizable under § 1983.

The district court also denied Hutcherson's request for an injunction or stay of his execution because there is no meaningful likelihood that Hutcherson can succeed on the merits, and there is a strong presumption against granting a stay where a claim could have been brought at such a time as to allow consideration of the merits without requiring entry of a stay. The district court noted that Hutcherson's arguments in his § 1983 complaint are not new. These same contentions were the moving force behind Hutcherson's second Rule 32 petition filed in November 2004 and his § 2254 petition filed in August 2004. Thus, Hutcherson was fully aware of the factual and legal bases for his claims in the present action for more than two years before he filed suit. Accordingly, the district court found that these facts indicated that Hutcherson had been dilatory in pursuing his claims, and this equitable ground formed a separate basis for the denial of injunctive relief sought in Hutcherson's § 1983 complaint. Hutcherson appealed the district court's denial of his § 1983 action to this court on October 20, 2006. We granted an expedited briefing schedule for the parties because of Hutcherson's pending execution date.

II. DISCUSSION

An inmate convicted and sentenced under state law may seek federal relief under two primary avenues: “a petition for habeas corpus, 28 U.S.C. § 2254, and a complaint under the Civil Rights Act of 1871, Rev. Stat. § 1979, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1983.” Hill, 126 S.Ct. at 2101. These avenues are mutually exclusive: if a claim can be raised in a federal habeas petition, that same claim cannot be raised in a separate § 1983 civil rights action. See Nelson, 541 U.S. at 643, 124 S.Ct. at 2122 (“[Section] 1983 must yield to the more specific federal habeas statute, with its attendant procedural and exhaustion requirements, where an inmate seeks injunctive relief challenging the fact of his conviction or the duration of his sentence.”).

The line of demarcation between a § 1983 civil rights action and a § 2254 habeas claim is based on the effect of the claim on the inmate's conviction and/or sentence. When an inmate challenges the “circumstances of his confinement” but not the validity of his conviction and/or sentence, then the claim is properly raised in a civil rights action under § 1983. Hill, 126 S.Ct. at 2101. However, when an inmate raises any challenge to the “lawfulness of confinement or [the] particulars affecting its duration,” his claim falls solely within “the province of habeas corpus” under § 2254. Id. Simply put, if the relief sought by the inmate would either invalidate his conviction or sentence or change the nature or duration of his sentence, the inmate's claim must be raised in a § 2254 habeas petition, not a § 1983 civil rights action. If the court determines that the claim does challenge the lawfulness of the inmate's conviction or sentence, then the court must treat the inmate's claim as raised under § 2254, and it must apply the AEDPA's attendant procedural and exhaustion requirements to the claim. See Nelson, 541 U.S. at 643, 124 S.Ct. at 2122.

On appeal, Hutcherson frames his issue for review as: “The failure, in capital cases, of the State of Alabama to provide for representation in the manner set out in the American Bar Association Guidelines for the appointment and performance of counsel in death penalty cases constitutes a denial of Larry Hutcherson's rights to counsel as envisioned in the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution and Due Process of Law as envisioned in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution and is actionable under 42 United States Code § 1983.” This claim, although restated, is in essence the same claim Hutcherson raised in his first federal habeas petition. The claim attacks the validity of Hutcherson's conviction and sentence, not the “circumstances of his confinement.” Hutcherson effectively asks the court to vacate his conviction and/or sentence on constitutional grounds (ineffective assistance of counsel), provide him a new trial or second round of collateral appeals, and prevent the State from re-trying him until the Alabama Legislature adopts the ABA Guidelines for Counsel in Death Penalty Cases as binding in Alabama. Thus, a fair reading of Hutcherson's claim establishes that his claim is a habeas claim and not a civil rights claim under § 1983. Because Hutcherson's § 1983 complaint is the functional equivalent of a habeas corpus petition, we consider whether Hutcherson can satisfy the procedural and exhaustion requirements set forth in AEDPA. Hutcherson fails to satisfy the requirements under 28 U.S.C. § 2244(b). See Court's Order denying Motion for Leave to File a Successive Habeas Petition entered on Oct. 24, 2006 (Appeal No. 06-15544).

Furthermore, we deny Hutcherson's motion for a stay of his execution pending appeal because Hutcherson cannot obtain relief on his § 1983 claim that is the functional equivalent of a habeas claim. Moreover, Hutcherson is not entitled to a stay based on the equities of his case. Hutcherson has waited until the eve of his execution to request relief in the form of an injunction or motion to stay. Hutcherson had knowledge of his pending execution date four months ago. Hutcherson's requested stay of execution is directly attributable to his own failure to bring his claims to court in a timely fashion. Since Hutcherson previously litigated the very claim he asserts on appeal of his § 1983 complaint, there is no reasonable basis for his decision to wait ten months after the dismissal of his first habeas corpus petition to re-style his claim as a § 1983 action. Accordingly, Hutcherson is not entitled to the equitable remedy of a stay of execution. AFFIRMED; MOTION FOR STAY OF EXECUTION DENIED.