Executed July 18, 2012 06:37 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Texas

24th murderer executed in U.S. in 2012

1301st murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

6th murderer executed in Texas in 2012

483rd murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(24) |

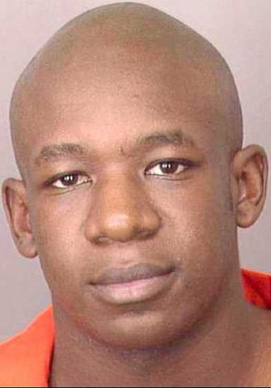

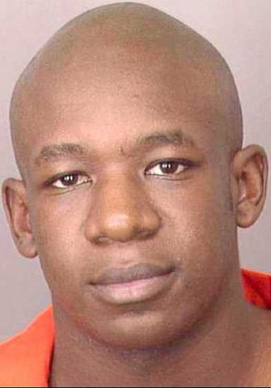

Yokamon Laneal Hearn B / M / 19 - 33 |

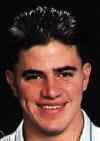

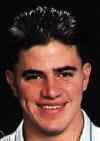

Frank Meziere W / M / 23 |

Diles pleaded guilty to capital murder and was sentenced to life in prison. Burley and Shirley both pleaded guilty to aggravated robbery and received 10-year sentences. They were discharged in 2008.

Citations:

Hearn v. State, No. 73,371, slip op. (Tex.Crim.App. Oct. 3, 2001). (Direct Appeal)

Ex parte Hearn, 310 S.W.3d 424 (Tex. Crim. App. 2010). (PCR)

Hearn v. Cockrell, 73 Fed.Appx. 79 (5th Cir. 2003). (Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Texas no longer offers a special "last meal" to condemned inmates. Instead, the inmate is offered the same meal served to the rest of the unit.

Final/Last Words:

"I'd like to tell my family that I love y'all and I wish y'all well. I'm ready."

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders (Hearn)

Hearn, Yokamon L.

Date of Birth: 11/6/78

DR#: 999292

Date Received: 12/31/98

Education: 10 years

Occupation: Unknown

Date of Offense: 3/26/98

County of Offense: Dallas

Native County: Dallas

Race: Black

Gender: Male

Hair Color: Black

Eye Color: Brown

Height: 5' 8"

Weight: 184

Prior Prison Record: None.

Summary of incident: On March 26, 1998, Hearn and 3 co-defendants approached the victim (a 26 year old white male) with a gun. They forced the victim into his own car, took him to a deserted area, and shot him 12 times in the head and upper body, resulting in his death. Hearn and the co-defendants took the victim's wallet and personal items and fled in the victim's vehicle.

Co-Defendants: Delvin Dites; Dwight Burley; Theresa Shirley

Friday, February 27, 2004

Media advisory: Yokamon Laneal Hearn scheduled for execution

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit temporarily stayed Yokamon Laneal Hearn's execution, requested supplemental briefing and heard oral argument. After reviewing the case, the high court granted Hearn's stay of execution and remanded the case to the district court.

Austin – Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott offers the following information about 25-year-old Yokamon Laneal Hearn, who is scheduled to be executed after 6 p.m. Thursday, March 4, 2004. On December 11, 1998, Hearn was sentenced to die for the capital murder of Frank Meziere in North Dallas in late March 1998.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

Evidence admitted at trial established that on March 25, 1998, then 19-year-old Hearn and three others drove to North Dallas for the expressed purpose of making some money. The group carried with them two shotguns, a .22 caliber pistol, and a Tec-9 automatic. At about 10:30 p.m. the group observed Frank Meziere preparing to wash his 1994 Mustang in a coin-operated car wash. Hearn devised a plan to steal the car and instructed his accomplices how to proceed. Hearn and his companions abducted Frank Meziere at gunpoint and drove him to a secluded location where Hearn used the Tec-9 to shoot Meziere. Meziere died as the result of multiple close-range gunshot wounds to the head. Hearn then drove away in Meziere’s Mustang in search of a “chop shop” for stolen cars. A city electrician discovered Meziere’s body in a roadside field early the next morning. Two hours later a patrol officer discovered Meziere’s abandoned Mustang in a shopping center parking lot.

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

March 31, 1998 – Hearn was indicted in the 282nd District Court of Dallas County, Texas.

December 11, 1998 – Hearn was sentenced to death.

Direct Appeal

October 3, 2001 – Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Hearn’s conviction and sentence.

April 15, 2002 – U.S. Supreme Court denied Hearn’s petition for writ of certiorari off direct appeal.

Habeas Proceedings

December 14, 2000 – Hearn filed application for writ of habeas corpus in the state trial court.

August 1, 2001 – The state trial court recommended that habeas relief be denied.

November 14, 2001 – Court of Criminal Appeals denied habeas corpus relief in an unpublished order.

March 4, 2002 - Hearn filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in the U.S. District Court.

July 11, 2002 – U.S. District Court denied Hearn’s request for federal habeas relief.

August 13, 2002 - U.S. District Court denied Hearn’s application for a Certificate of Appealability.

June 25, 2003 – The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denied Hearn’s request for COA

September 22, 2003 – Hearn filed a petition for writ of certiorari in the U.S. Supreme Court.

November 17, 2003 – Supreme Court denied Hearn’s petition for writ of certiorari.

CRIMINAL HISTORY

During the punishment phase of Hearn’s trial, the jury learned that he had be been involved in numerous prior offenses including the burglaries of four habitations, arson, an aggravated robbery, an aggravated assault, a sexual assault, a terroristic threat combined with unlawful carrying of a weapon, a criminal trespass to steal a bicycle, and a schoolyard assault over another bicycle.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Yokamon Laneal Hearn, 33, was executed by lethal injection on 18 July 2012 in Huntsville, Texas for the kidnapping, murder, and robbery of a 26-year-old man.

In the evening of 26 March 1998, Hearn, then 19, and Delvin Diles, also 19, approached Frank Meziere, 23, at a coin-operated car wash in North Dallas. They forced Meziere at gunpoint into his own car, then drove to a deserted area. Two other companions, Dwight Burley, 20, and Teresa Shirley, 19, followed in a second car. Hearn and Diles then shot Meziere several times in the head and upper body. The assailants then took the victim's wallet and personal items and fled in his vehicle. Meziere's body was discovered the next morning. He had twelve bullet wounds from 9 mm and .22-caliber weapons. His car was also discovered later that morning, abandoned in a shopping center parking lot. Hearn and his companions were caught on videotape by a security camera at a convenience store adjacent to the car wash. Hearn and Diles were arrested several days later. Burley and Shirley were arrested eight months later.

At Hearn's trial, Teresa Shirley testified that she was the driver of the second car. She said that Meziere had his arms raised and appeared to be begging for his life as Hearn swung a Tec-9 semiautomatic rifle back and forth. The rifle, Shirley testified, had been stolen in an apartment burglary the previous day. Hearn fired at Meziere and kept shooting him even after he fell to the ground. Diles also shot at the victim several times with his revolver, she testified. Shirley further testified that Hearn later bragged about the killing. She said he waved around a newspaper account stating that Meziere had been shot in the head - or "domed" in street slang, and he told her, "I told you I domed him. I told you. I told you."

At age 19, Hearn had no prior felony convictions. Testimony at his punishment hearing indicated that he had an unadjudicated history of burglary, robbery, sexual assault, and other offenses. A jury convicted Hearn of capital murder in December 1998 and sentenced him to death. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the conviction and sentence in October 2001.

Hearn had previously been scheduled for execution on 4 March 2004, but on that day, he received a last-hour stay from the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals so that his attorneys' claims that he was mentally retarded could be further investigated. The federal courts ultimately rejected this claim, as did the state courts when they reconsidered the issue in 2010. All of his subsequent appeals in state and federal court were denied. Delvin Juan Diles pleaded guilty to capital murder and was sentenced to life in prison. He remains in custody as of this writing. Dwight Paul Burley and Teresa Shavonn Shirley both pleaded guilty to aggravated robbery and received 10-year sentences. They were discharged in December 2008 and November 2008, respectively.

"I'd like to tell my family that I love y'all and I wish y'all well," Hearn said in his brief last statement at his execution. "I'm ready." The lethal injection was then started. He was pronounced dead at 6:37 p.m.

Hearn was the first prisoner in Texas to be executed using only one chemical. Historically, Texas and other the other states using lethal injection administered a series of three drugs to perform executions. In 2011, however, the first drug, sodium thiopental, became scarce due to a manufacturer's decision to cease producing it. Some states, including Texas, switched to pentobarbital for the first drug in the series, while Ohio eliminated the three-drug protocol and began using pentobarbital alone. Texas switched to a single dose of pentobarbital for Hearn's execution because its supply of the second drug in the series - pancuronium bromide - had expired.

"Texas conducts its first one-drug execution," by Corrie MacLaggan. (Wed Jul 18, 2012 8:37pm EDT)(Reuters) - Texas on Wednesday carried out its first execution since the state switched this month to a one-drug protocol for lethal injections because a supply of another drug is no longer available. Yokamon Hearn, 33, who had a long criminal history, was executed for the 1998 abduction and fatal shooting of 23-year-old stockbroker Frank Meziere in Dallas. "The execution was carried out without incident," said Jason Clark, a spokesman for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

Texas, which executes more people than any other U.S. state, had been using a three-drug cocktail to carry out executions but will now use only pentobarbital, a sedative sometimes used to euthanize animals. The state made the switch because its available supply of another drug in the cocktail, pancuronium bromide, expired and was no longer usable. "The one-drug protocol has been adopted by several states, and has been upheld as constitutional by the courts," Clark said in an email.

On Tuesday, Georgia postponed an execution that also had been scheduled for Wednesday as it prepared to use pentobarbital alone instead of three drugs in its lethal injections.

On March 25, 1998, Hearn and three others kidnapped Meziere at a self-service car wash. Hearn shot him at close range and then drove off in Meziere's Mustang, according to the Texas Attorney General's Office. Meziere's body was found the next morning in a field with gunshot wounds to the head and face. Witnesses testified at Hearn's trial that he bragged about the killing, waving a newspaper story about the crime, according to Dallas Morning News reports from 1998.

The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals granted Hearn a reprieve on the day he was scheduled to be executed in 2004 after he indicated he wanted to raise a claim that he had mental disabilities.

Hearn was the sixth inmate put to death in Texas this year and the 24th in the United States, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Clark said Hearn's final statement was: "Yes, I would like to tell my family that I love y'all and I wish y'all well. I'm ready."

"State carries out 1st single drug execution," by Cody Stark. (July 18, 2012)

HUNTSVILLE — A 33-year-old man condemned to die for the 1998 slaying of a Dallas stockbroker became the first Texas death row inmate to be executed using a single drug Wednesday. Yokamon Hearn was pronounced dead at 6:37 p.m., 25 minutes after the lethal does began. It did not appear that he had any unusual reactions to the single dose as he became the sixth person executed in Texas this year.

He did not mention the crime for what he was put to death for, but he did make a final statement. “I’d like to tell my family I love y’all and I wish y’all well. I’m ready,” Hearn said. After the lethal dose was administered, Hearn closed his eyes and began snoring before passing.

About 3 1/2 hours before Hearn’s execution, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected appeals to halt it. None of the appeals addressed the change in the state’s execution drug policy.

Last week the Texas Department of Criminal Justice announced it would switch from a three-drug combination used since 1982 to a single dose of the sedative pentobarbital for executions following a drug shortage. The state’s supply of pancuronium bromide, a muscle relaxant mixed with potassium chloride (used to stop the heart) and pentobarbital, expired. Texas began using pentobarbital last year when another drug, sodium thiopental, became unavailable when its European supplier stopped making it.

Hearn was convicted and sentenced to die for the murder and carjacking of 23-year-old Frank Meziere of Plano on March 26, 1998. Evidence during the trial revealed that Meziere was cleaning his car at a self-service car wash in Dallas when Hearn and a group of friends approached. The victim was forced into his own car at gunpoint and taken to a deserted area where he was shot 12 times in the head and upper body and dumped on the side of the road. Hearn and his co-defendents took Meziere’s car and other personal items before fleeing the scene.

Jason January, the former Dallas County assistant district attorney who prosecuted Hearn, read a statement on behalf of the Meziere family. “... We have been asked many times if this execution would give the family closure. There is no closure when you lose your child, especially in the violent and senseless way we lost Frank,” January read. “A life ending at age 23 for no reason other than someone else’s greed is hard to understand. “We have lost a son, a brother, a grandson and a friend to many, many people. We did not come today to view this execution as revenge or to even the score. What this has done is give our family and friends the knowledge that Mr. Hearn will not have the opportunity to hurt anyone else. He will not have the opportunity to take another life.”

Hearn, known to his friends as “Yogi,” was 19 at the time of Meziere’s murder and had a lengthy record that included burglary, robbery, assault, sexual assault and weapons possession. One of Hearn’s companions received life in prison. Two others got 10-year sentences.

"Texas executes its 1st inmate using single drug," by Michael Graczyk. (AP Wednesday, July 18, 2012)

HUNTSVILLE, Texas (AP) — A Texas man convicted of carjacking and fatally shooting a stockbroker was put to death Wednesday, becoming the first prisoner in the nation's most active capital punishment state to be executed under a procedure using one lethal drug instead of three.

Texas Department of Criminal Justice officials announced last week they were modifying the three-drug injection method used since 1982 because the state's supply of one of the drugs — the muscle relaxant pancuronium bromide — has expired. Yokamon Hearn, 33, was executed using a single dose of the sedative pentobarbital, which had been part of the three-drug mixture since last year. Ohio, Arizona, Idaho and Washington have already adopted a single-drug procedure, and this week Georgia said it would do so, too.

Hearn showed no apparent unusual reaction to the drug as his execution began. He was pronounced dead about 25 minutes after the lethal dose began flowing. Asked by the warden if he wanted to make a statement, he said: "I'd like to tell my family that I love y'all and I wish y'all well. I'm ready."

Hearn was condemned for the March 1998 slaying of 23-year-old suburban Dallas stockbroker Frank Meziere. About 3½ hours before Hearn was put to death, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected his appeals to halt the execution. None of the appeals addressed the change in the state's execution drug policy. Evidence showed Meziere, of Plano, was cleaning his black convertible Mustang at a self-service car wash in Dallas when Hearn, then 19, and his friends approached. They forced Meziere at gunpoint into his own car and drove him to an industrial area in a south Dallas neighborhood, where he was shot 10 times in the head.

Meziere's father, brother and uncle were among those who witnessed Hearn's lethal injection. "We did not come today to view this execution for revenge or to even the score," the family said afterward in a statement. "What this does is give our family and friends the knowledge that Mr. Hearn will not have the opportunity to hurt anyone else."

Hearn, known to his friends as "Yogi," already had a lengthy record that included burglary, robbery, assault, sexual assault and weapons possession.

In one appeal, Hearn's lawyers argued that his mother drank alcohol when she was pregnant, stunting his neurological development and leaving him with mental impairments that disqualify him from execution under earlier Supreme Court rulings. Testing shows Hearn's IQ is too high for him to be considered mentally impaired. In another, his appeals lawyers claimed the trial attorneys who handled his initial appeals failed to investigate his background and uncover evidence of his alleged mental impairment and troubled childhood.

Before the Supreme Court issued brief one-paragraph rulings rejecting his two appeals, Richard Burr, one of Hearn's lawyers, had acknowledged "a degree of hope, but still, it'll be tough." State attorneys contested the appeals, arguing that information about Hearn's background and upbringing had been "thoroughly investigated and addressed at trial" and that the evidence "does not substantiate any scenario other than that of Hearn's guilt." Georgette Oden, an assistant Texas attorney general, argued Hearn's latest appeal was improperly filed this week by circumventing lower courts and that it should have been filed years ago.

Hearn declined to speak with reporters in the weeks leading up to his execution. In 2004, he avoided the death chamber when a federal court agreed his mental impairment claims should be reviewed and halted his execution less than an hour before its scheduled time.

Jason January, the former Dallas County assistant district attorney who prosecuted Hearn for capital murder, said to stop the punishment because of fetal alcohol syndrome "would be a free pass for anyone whose parents drank." "No question he had a tough background, but a lot of people have tough backgrounds and work their way out and don't fill someone's head with 10 bullets," he said.

One of Hearn's accomplices received life in prison. Two others got 10-year sentences. Hearn became the sixth Texas prisoner executed this year and the 483rd since 1982. At least eight other Texas prisoners have execution dates in the coming months, including three in August.

UPDATE — He’s dead. Justice has finally been served.

A Texas man convicted of carjacking and fatally shooting a stockbroker was put to death Wednesday, becoming the first prisoner in the nation’s most active capital punishment state to be executed under a procedure using one lethal drug instead of three. Well…I”m guessing the one-drug protocol works just fine, then.

You might not be very bright, Yogi, but you’re just smart enough to die for your crimes

•Thug: Yokamon L. Hearn (19 at time of offense)

•Date of Execution: July 18, 2012, sometime shortly after 6:00 pm HTT

•Date of Crime: March 26, 1998

•Victim(s): Frank Meziere (26)

•Last Meal: Same shit salad being fed to every other thug on the row that day

•Final Words: ”I’d like to tell my family that I love y’all and I wish y’all well. I’m ready.”

Hearn has been sentenced to die for the capital murder of Frank Meziere in North Dallas in late March 1998. He is scheduled go pay for his crimes with his life on Wednesday, July 18, 2012.

Facts of the Crime

Evidence admitted at trial established that on March 25, 1998, then 19-year-old Yokamon (Yogi) Hearn and three others (Delvin Dites, Dwight Burley, and Theresa Shirley) drove to North Dallas for the expressed purpose of making some money. The group carried with them two shotguns, a .22 caliber pistol, and a Tec-9 automatic. At about 10:30 p.m. they found Frank Meziere at a coin-operated car wash with his 1994 Mustang. Following Hearn’s plan, he and his fellow PoS thugs car jacked Frank Meziere at gunpoint and drove him to a secluded location where Hearn used the Tec-9 to shoot Meziere in the head 12 times.

Shirley testified against Yogi that Meziere had his arms raised near his head and appeared to beg for his life as Hearn swung the Tec-9, a 9 mm assault-style rifle stolen from an apartment the previous day, back and forth before opening fire. After the victim hit the ground, Hearn shot him several more times, she said. Diles added some shots from his revolver. Hearn then stole Meziere’s Mustang in search of a “chop shop” for stolen cars. A city electrician discovered Meziere’s body in a roadside field early the next morning. Two hours later a patrol officer discovered Meziere’s abandoned Mustang in a shopping center parking lot.

Diles, 19 at the time, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to consecutive life terms for Meziere’s death and an unrelated aggravated robbery. He and Hearn were arrested within days of the slaying. Shirley, then 19, and Burley, then 20, were arrested more than eight months later. Each pleaded guilty to aggravated robbery and received 10-year prison sentences.

Prior Criminal History

During the punishment phase of Hearn’s trial, the jury learned that he had be been involved in numerous prior offenses including the burglaries of four homes, arson, an aggravated robbery, an aggravated assault, a sexual assault, a terroristic threat combined with unlawful carrying of a weapon, a criminal trespass to steal a bicycle, and a schoolyard assault over another bicycle. You would expect a person found guilty of that number and seriousness of offenses (all by the tender age of 19) to already be locked up to keep society safe. You would be wrong.

Second Time’s a Charm

Yokamon was initially set to die on Thursday, March 4, 2004, but was granted a stay about 15 minutes before his date with the needle, pending an appeal as to whether or not Hearn was retarded (which is the entirety of his defense…not that he didn’t shoot Meziere in the head a dozen times, but rather that he’s retarded. The court has ruled that he is not, and that he can be put to death for his crimes. This should not have taken 12 years.

Yogi will also be the first inmate put to death here in Texas using the new 1-drug protocol.: Texas will join a handful of states that use a single drug in lethal injections, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice announced Tuesday. “Implementing the change in protocol at this time will ensure that the agency is able to fulfill its statutory responsibility for all executions currently scheduled,” TDCJ spokesman Jason Clark said in an email.

For Yokamon Hearn’s scheduled execution on July 18, officials plan to administer a lethal dose of pentobarbital instead of the three-drug cocktail that has been used since Texas reinstated the death penalty in 1982. Clark said the decision to change the protocol came because the state’s supply of one of the other drugs that had been used in the protocol — pancuronium bromide — had expired and TDCJ was unable to obtain more. If all goes as it should, Hearn would become the 483rd inmate executed in Texas since reinstatement of the death penalty and the 244th inmate to die on Gov. Rick Perry’s watch (good job, Gov. Perry).

Yokamon Hearn was sentenced to death for the carjacking and fatal shooting of a Dallas-area stockbroker. Acting on a tip in March of 1998, police arrested Yokamon Hearn and Delvin Diles just after midnight at a room in the Delux Inn. They abducted Frank Meziere, 23, of Plano, at a carwash, taking him to an industrial area of east Oak Cliff and shooting him repeatedly in the head. Some men driving to work about 6 a.m. the next day spotted his body in a patch of grass. Meziere's car was found about an hour later.

Police said they had determined that Hearn and Diles carjacked Meziere when he pulled into a carwash. A police spokesman said that "they forced him into his car and drove to the murder scene." Meziere's father said that "I just hope justice can be done as soon as possible. I've always been in favor of the death penalty, and I stand by that now." Dallas County criminal records showed Diles had received 5 years of probation the previous summer after pleading guilty to a felony burglary charge; Hearn had been charged with misdemeanor theft, a case which was still pending at the time of Frank's murder.

UPDATE: Frank Meziere had watched a Dallas Mavericks basketball game at a restaurant with a friend and before heading home stopped at a self-service car wash to clean his black Mustang convertible. The 23-year-old Plano stockbroker, a 1996 Texas A&M University graduate, never made it home. His body was found the next day, March 26, 1998, along the side of a road in an industrial area of Oak Cliff, an area of south Dallas. He had been shot in the head 10 times. His car was found about 5 miles away, abandoned and with the lights on.

"Having dealt with murders, you think you've seen it all," said Jason January, a former Dallas County assistant district attorney. "But this innocent victim was shot almost for sport. "It was just the sheer overkill of the thing that was ludicrous." Yokamon Hearn bragged to friends about how he "domed" Meziere, meaning he shot him in the head. Hearn was set to die Thursday evening for the slaying.

In an appeal filed this week, lawyers for Hearn said the inmate may be mentally retarded and asked the courts to halt the punishment so they can pursue their claim. The U.S. Supreme Court has barred execution of the mentally retarded. Prosecutors said questions about Hearn's mental competence never surfaced previously. Hearn, 25, refused to speak with reporters as his execution date neared. The U.S. Supreme Court in November denied his request seeking a review of his case. "It's hard sometimes to know what a death penalty case is, but after a while you know one when you see it," said January, the lead prosecutor at Hearn's trial. "And this just screamed out for the death penalty." Dallas jurors agreed, deliberating less than an hour to convict Hearn and about an hour before deciding on punishment. Hearn was 19 at the time of the crime and had a lengthy record that included burglary, robbery, assault, a sexual assault and weapons possession. "I remember having a big map of the city showing places he had hit and pulled guns on people," January recalled this week. "He was an equal opportunity carjacker -- women, black, white, everybody."

Hearn, along with 2 other Dallas men and one woman from Oklahoma City, were seen on a security camera video at a convenience store adjacent to the car wash. They had been out looking for someone to carjack, authorities said. According to testimony at his trial, Hearn drove Meziere's car after he and companion Delvin Diles forced the victim into the car. The two others, Dwight Burley and Teresa Shirley, were in a second car in a convoy that took them to an area near Dallas' wastewater treatment plant. Meziere was shot there with a Tec-9 automatic, then with a .22-caliber pistol. Hearn drove off with his car. Shirley, driver of the 2nd car, testified Meziere had his arms raised near his head and appeared to beg for his life as Hearn swung the Tec-9, a 9 mm assault-style rifle stolen from an apartment the previous day, back and forth before opening fire. After the victim hit the ground, Hearn shot him several more times, she said. Diles added some shots from his revolver. Hearn drove off with Meziere's car and kept the victim's license. A witness testified at his trial that Hearn later bragged at a party about the shooting.

Physical evidence linked both Hearn and Diles to the car. Diles, 19 at the time, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to consecutive life terms for Meziere's death and an unrelated aggravated robbery. He and Hearn were arrested within days of the slaying. Shirley, then 19, and Burley, then 20, were arrested more than 8 months later. Each pleaded guilty to aggravated robbery and received 10-year prison sentences.

UPDATE: A condemned inmate described by a prosecutor as an "equal opportunity carjacker" was spared Thursday evening less than an hour before he could have been taken to the Texas death chamber for killing a Dallas-area man who was shot 10 times in the head. Yokamon Hearn, 25, was facing lethal injection for the 1998 fatal shooting of Frank Meziere, a 23-year-old Plano stockbroker abducted at gunpoint from a self-service car wash in Dallas six years ago. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with defense attorneys who sought a delay in their late appeals and stopped the punishment, but the court also set an accelerated briefing schedule to ensure the appeals would not be prolonged, Lori Ordiway, an assistant district attorney in Dallas County, said. The death warrant allowed the execution to be carried out after 6 p.m. although state officials normally wait until all appeals are resolved before moving ahead with the lethal injection. In the appeal before the New Orleans-based 5th Circuit, lawyers contended Hearn may be mentally retarded and wanted time to pursue the claim. The U.S. Supreme Court has barred the execution of the mentally retarded.

Ex parte Hearn, 310 S.W.3d 424 (Tex. Crim. App. 2010) (PCR)

Background: Death-sentenced applicant filed application for post-conviction relief based on claim of mental retardation. The 282nd District Court, Dallas County, Karen J. Treene, J., transferred application to Court of Criminal Appeals.

Holding: The Court of Criminal Appeals, Johnson, J., held that applicant failed to establish that he was mentally retarded. Application dismissed.

JOHNSON, J., delivered the opinion for a unanimous Court.

Applicant, Yokamon Laneal Hearn, was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death. In this subsequent application for habeas corpus, applicant asserts that he is mentally retarded and, pursuant to the United States Supreme Court holding in Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304, 122 S.Ct. 2242, 153 L.Ed.2d 335 (2002), constitutionally exempt from a death sentence.

In our statutes and case law, “mental retardation” is defined by: (1) significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning; (2) accompanied by related limitations in adaptive functioning; (3) the onset of which occurs prior to the age of 18. Ex parte Briseno, 135 S.W.3d 1, 7 n. 26 (Tex.Crim.App.2004) (citing American Association of Mental Retardation (AAMR), Mental Retardation: Definition, Classification, and Systems of Support 5 (9th ed. 1992)). See also American Association on Mental Deficiency (AAMD), Classification in Mental Retardation 1 (Grossman ed. 1983). The issue before this court is whether alternative assessment measures can be substituted for full-scale IQ scores in supporting a finding of subaverage intellectual functioning. We hold that alternative assessment measures can not be substituted for full-scale IQ scores.

Procedural History

In December 1998, applicant was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death. This Court affirmed his conviction and sentence,FN1 and the United States Supreme Court denied his petition for writ of certiorari. FN2

FN1. Hearn v. State, No. 73,371, slip op. (Tex.Crim.App. Oct. 3, 2001). FN2. Hearn v. Texas, 535 U.S. 991, 122 S.Ct. 1547, 152 L.Ed.2d 472 (2002).

While his appeal was pending in this Court, applicant filed his initial application for writ of habeas corpus in the 282nd District Court of Dallas County (state district court). That court recommended that all relief be denied. Ex parte Hearn, No. W98–46232–S(A) (282nd Dist. Ct., Dallas County, Aug. 1, 2001). Upon review of the record, this Court denied relief in an unpublished order. Ex parte Hearn, No. 50,116–01 (Tex.Crim.App. Nov. 14, 2001).

Subsequently, applicant sought habeas corpus relief from his conviction and sentence in federal court. The United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas (federal district court) denied relief on his application for writ of habeas corpus. Hearn v. Cockrell, 2002 WL 1544815 (N.D.Tex. July 11, 2002). Thereafter, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (Fifth Circuit) FN3 and the United States Supreme Court FN4 each refused applicant's petitions for review. FN3. Hearn v. Cockrell, 73 Fed.Appx. 79 (5th Cir.2003). FN4. Hearn v. Dretke, 540 U.S. 1022, 124 S.Ct. 579, 157 L.Ed.2d 440 (2003).

After the United States Supreme Court refused applicant's petition for writ of certiorari, applicant's counsel concluded her representation of applicant. Applicant then sought the help of the Texas Defender Service. In March 2004, with the assistance of the Texas Defender Service attorneys, applicant filed a motion for stay of execution and appointment of counsel to assist him in investigating an Atkins claim. We denied both requests, finding that applicant failed to make a prima facie showing of mental retardation. Ex parte Yokamon Laneal Hearn, No. 50,116–02 (Tex.Crim.App. Mar. 3, 2004).

At about the same time, in the federal district court, applicant moved for appointment of counsel and stay of execution. The federal district court transferred the motions to the Fifth Circuit sua sponte. Applicant then filed a separate notice of appeal, asking the Fifth Circuit to reverse the order, appoint counsel, and stay the execution. The Fifth Circuit granted a stay of execution in order to determine whether applicant was entitled to counsel and services under 21 U.S.C. § 848(q). It held that applicant was entitled to such counsel, granted applicant's request for appointment of counsel, and remanded his case to the federal district court. In re Hearn and Hearn v. Dretke, 376 F.3d 447 (5th Cir.2004), reh. denied, 389 F.3d 122 (5th Cir.2004).

On remand, the federal district court held that applicant had not made a showing of mental retardation, as is required in order to proceed on his successive habeas corpus petition. Hearn v. Quarterman, 2007 WL 2809908 (N.D.Tex. Sep.27, 2007). Applicant then filed a Rule 59(e) motion to vacate the judgment and supported that motion with two new expert reports. After reviewing these reports, the federal district court held that applicant did make a prima facie case for an Atkins claim and stayed the federal proceedings to allow applicant to present his Atkins claim to the state court. Hearn v. Quarterman, 2008 WL 3362041 (N.D.Tex. Aug.12, 2008).

In October 2008, applicant filed, in the state district court, a subsequent application that is based on an Atkins claim and seeks post-conviction relief from his death sentence. It was forwarded to this Court in June 2009. In September 2009, the Court filed and set this case in order to determine whether alternative-assessment measures can be substituted for full-scale IQ scores in supporting a finding of subaverage intellectual functioning.

Applying Atkins

In Atkins, the Supreme Court held that executing persons who are mentally retarded is a violation of the Eighth Amendment. Atkins, 536 U.S. at 320, 122 S.Ct. 2242. The Supreme Court “le[ft] to the States the task of developing appropriate ways to enforce the constitutional restriction upon their execution of sentences.” Id. at 317, 122 S.Ct. 2242. Post- Atkins, we have received a significant number of habeas corpus applications from death row inmates who allege they suffer from mental retardation and are therefore exempt from execution. “This Court does not, under normal circumstances, create law. We interpret and apply the law as written by the Texas Legislature or as announced by the United States Supreme Court.” Briseno, 135 S.W.3d at 4. However, the Texas Legislature has not yet enacted legislative guidelines for enforcing the Atkins mandate. Consequently, we have set out guidelines by which to address Atkins claims until the legislature acts. Briseno, 135 S.W.3d at 4.

In Briseno we announced that “[u]ntil the Texas Legislature provides an alternate statutory definition of ‘mental retardation,’ ... we will follow the AAMR or section 591.003(13) of the Texas Health and Safety Code criteria in addressing Atkins mental retardation claims.” FN5 Briseno, 135 S.W.3d at 8. The AAMR defines mental retardation as a disability characterized by: (1) significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning; (2) accompanied by related limitations in adaptive functioning; (3) the onset of which occurs prior to the age of 18.FN6 Briseno, 135 S.W.3d at 7 n. 26 (citing AAMR at 5). See also AAMD at 1.

FN5. According to § 591.003(13) of the Texas Health and Safety Code, mental retardation “means significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning that is concurrent with deficits in adaptive behavior and originates during the developmental period.” Tex. Health & Safety Code § 591.003(13). FN6. A jury determination of mental retardation is not required. Briseno, 135 S.W.3d at 9.

Determining whether one has significantly subaverage intellectual functioning is a question of fact. It is defined as an IQ of about 70 or below.FN7 American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 41 (DSM–IV). There is “a measurement error of approximately 5 points in assessing IQ,” which may vary from instrument to instrument.FN8 Id. Thus, any score could actually represent a score that is five points higher or five points lower than the actual IQ. Id.; see also Wilson v. Quarterman, 2009 WL 900807 *4 (E.D.Tex. Mar.31, 2009).

FN7. General intellectual functioning is defined by the intelligence quotient (IQ). It is obtained by assessment with a standardized, individually administered intelligence test (i.e. Wechsler Intelligence Scales for Children, 3rd Edition; Stanford–Binet, 4th Edition; and Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children). DSM–IV at 41. FN8. A Wechsler IQ score of 70 would represent a score range of 65 to 75. DSM–IV at 41.

The IQ score is not, however, the exclusive measure of mental retardation. A finding of mental retardation also requires a showing of “significant limitations in adaptive functioning.” DSM–IV at 41. According to the AAMR, three adaptive-behavior areas are applicable to determining mental retardation: conceptual skills, social skills, and practical skills.FN9 Limitations in adaptive behavior can be determined by using standardized tests. FN10 According to the DSM–IV, “significant limitation” is defined by a score of at least two standard deviations below either (1) the mean in one of the three adaptive behavior skills areas or (2) the overall score on a standardized measure of conceptual, social, and practical skills. Id. Although standardized tests are not the sole measure of adaptive functioning, they may be helpful to the factfinder, who has the ultimate responsibility for determining mental retardation.

FN9. Conceptual skills include skills related to language, reading and writing, money concepts, and self-direction. Social skills include skills related to interpersonal relationships, responsibility, self-esteem, gullibility, naivete, following rules, obeying laws, and avoiding victimization. Practical skills are skills related to activities of daily living and include occupational skills and maintaining a safe environment. AAMR at 82. FN10. Several scales that have been designed to measure adaptive functioning: Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, the AAMR Adaptive Behavior Scale, the Scales of Independent Behavior, and the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System. DSM–IV at 42; Ex parte Woods, 296 S.W.3d 587, 596–97 (Tex.Crim.App.2009); Hunter v. State, 243 S.W.3d 664 at 670–71 (Tex.Crim.App.2007).

In addition to demonstrating that one has subaverage intellectual functioning and significant limitations in adaptive functioning, he or she must demonstrate that the two are linked—the adaptive limitations must be related to a deficit in intellectual functioning and not a personality disorder. To help distinguish the two, this court has set forth evidentiary factors that “fact-finders in the criminal trial context might also focus upon in weighing evidence as indicative of mental retardation or of a personality disorder.” FN11 Briseno, 135 S.W.3d at 8.

FN11. This court has set forth the following evidentiary factors: Did those who knew the offender during the developmental stage—his family, friends, teachers, employers, authorities—think he was mentally retarded at that time, and, if so, act in accordance with that determination? Has the person formulated plans and carried them through or is his conduct impulsive? Does his conduct show leadership or does it show that he is led around by others? Is his conduct in response to external stimuli rational and appropriate, regardless of whether it is socially acceptable? Does he respond coherently, rationally, and on point to oral and written questions or do his responses wander from subject to subject? Can the person hide facts or lie effectively in his own or others' interests? Putting aside any heinousness or gruesomeness surrounding the capital offense, did the commission of that offense require forethought, planning and complex execution of purpose? Briseno, 135 S.W.3d at 8–9.

Applicant's prima facie case for mental retardation

In 2005, defense psychologist Dr. Alice Conroy administered a WAIS–III test to applicant; applicant obtained a full-scale IQ score of 74. Defense expert Dr. James Patton concluded that applicant's full scale IQ score of 74 was within the standard error of measurement.FN12 Therefore, applicant argues that because his IQ score of 74 is within the standard error of measurement, he has met the requirement of significant subaverage intellectual functioning. FN12. Dr. Watson specifically stated that applicant's full-scale score of 74 is “in the IQ range that can be considered approximately two standard deviations below the mean of 100.” Applicant's Habeas Application, Ex. 2 at 46.

However, three additional IQ test scores yielded results that are materially above 70. In January 2007, the district court held an evidentiary hearing on applicant's Atkins claim. In preparation for the hearing, the two state experts administered the WAIS–III and Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales (5th Edition). Applicant's resulting full-scale IQ scores on those tests were 88 and 93 respectively.FN13 FN13. An entry in the clinic notes of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice-institutional division on January 5, 1999, notes that applicant's estimated full-scale IQ on a WAIS–R short-form test was 82.

The defense then asked Dr. Dale G. Watson to review applicant's previous test results. As a part of his evaluation of applicant's mental health, Dr. Watson administered an additional IQ test using the Woodcock Johnson Test of Cognitive Abilities (3rd Edition); applicant's resulting full-scale IQ score on that test was 87. Id. After reviewing applicant's results on that test, Dr. Watson found that it did not demonstrate subaverage intellectual functioning, but did demonstrate deficits in adaptive behavior.FN14 In an effort to better understand the inconsistency between applicant's above–70 full-scale IQ scores and his significant deficits in adaptive functioning, Dr. Watson administered a neuropsychological test battery. After reviewing the results, Dr. Watson concluded that applicant's neuropsychological deficits “appear” to underlie previous findings of deficits in adaptive functions, and are “likely” developmental in nature. FN14. Dr. Watson testified that there were errors in the scoring of the WAIS–III completed by Dr. Conroy and the WAIS–III completed by Dr. Price. None of the errors changed any score by more than one point.

The defense then asked Dr. Stephen Greenspan to consider whether neuropsychological deficits such as those revealed by neuropsychological testing of applicant could satisfy the requirement of significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning, despite full-scale IQ scores ranging from 87 to 93. Dr. Greenspan opined that substituting neuropsychological measures for full-scale IQ scores is “justified when there is a medical diagnosis of a brain syndrome or lesion, such as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder ... because it is well known that such conditions cause a mixed pattern of intellectual impairments that, while just as serious and handicapping as those found in people with a diagnosis of MR, are not adequately summarized” by full-scale IQ scores.FN15 Dr. Greenspan concluded that, under a more expansive definition of mental retardation, applicant could establish a mental-retardation claim.

FN15. Dr. Pablo Stewart previously found that applicant suffers from Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Dr. Greenspan adopted this finding in conducting his evaluation of applicant's mental health. Applicant's Habeas Application, Ex. 4 at 64–65. Dr. Greenspan also noted that, in the past, other experts have argued that “full-scale IQ is not an adequate indicator of significant intellectual impairment in someone with brain damage,” and that extremely deficient verbal IQ could be a better index. Id. at 11–12 (discussing People v. Superior Court (Vidal), 40 Cal.4th 999, 56 Cal.Rptr.3d 851, 155 P.3d 259 (2007)).

In view of all the evidence, applicant argues that he is mentally retarded. He notes that, in spite of the new IQ test results, Dr. Patton concluded that applicant is mentally retarded. “Neuropsychological testing, together with the diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome, has demonstrated that the significant limitations I have identified in Mr. Hearn's adaptive behavior are, nevertheless, a product of intellectual deficits.... I am satisfied that Mr. Hearn has mental retardation.” Id. In making his Atkins claim, applicant asks this Court to significantly alter the current definition of mental retardation. Applicant correctly notes that the assessment of “about 70 or below” is flexible; “[s]ometimes a person whose IQ has tested above 70 may be diagnosed as mentally retarded while a person whose IQ tests below 70 may not be mentally retarded.” FN16 Briseno, 135 S.W.3d at 7 n. 24 (citing AAMD at 23). Applicant, however, misconstrues this language to mean that clinical judgment can completely replace full-scale IQ scores in measuring intellectual functioning.

FN16. The AAMD states that, “[t]he maximum specified IQ is not to be taken as an exact value, but as a commonly accepted guideline” and that “clinical assessment must be flexible.” AAMD at 22.

This court has expressly declined to establish a “mental retardation” bright-line exemption from execution without “significantly greater assistance from the [ ] legislature.” Briseno, 135 S.W.3d at 6. Instead, this court interprets the “about 70” language of the AAMR's definition of mental retardation to represent a rough ceiling, above which a finding of mental retardation in the capital context is precluded. FN17. See, e.g., Ex parte Woods, 296 S.W.3d at 608 n. 35 & 36; Williams, 270 S.W.3d at 132; Neal v. State, 256 S.W.3d 264, 273 (Tex.Crim.App.2008); Hunter, 243 S.W.3d at 671; Gallo v. State, 239 S.W.3d 757, 771 (Tex.Crim.App.2007); Ex parte Blue, 230 S.W.3d 151, 165 (Tex.Crim.App.2007); Ex parte Lewis, 223 S.W.3d 372, 378 n. 21 (Cochran, J. concurring) (Tex.Crim.App.2006); Hall v. State, 160 S.W.3d 24, 36 (Tex.Crim.App.2004); Briseno, 135 S.W.3d at 14 n. 53. Compare, Ex parte Van Alstyne, 239 S.W.3d 815 (Tex.Crim.App.2007); Ex parte Bell, 152 S.W.3d 103 (Tex.Crim.App.2004); Ex parte Modden, 147 S.W.3d 293 (Tex.Crim.App.2004).

In the present case, applicant attempts to use neuropsychological measures to wholly replace full-scale IQ scores in measuring intellectual functioning.FN18 However, this court has regarded non-IQ evidence as relevant to an assessment of intellectual functioning only where a full-scale IQ score was within the margin of error for standardized IQ testing. FN19 Thus, we hold that, while applicants should be given the opportunity to present clinical assessment to demonstrate why his or her full-scale IQ score is within that margin of error, applicants may not use clinical assessment as a replacement for full-scale IQ scores in measuring intellectual functioning.

FN18. In support, applicant cited Dr. Greenspan's conclusion that substituting neuropsychological measures for full-scale IQ in cases of apparent brain damage “is justified when there is a medical diagnosis of a brain syndrome or lesion, such as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder.” Applicant's Habeas Application, Ex. 4 at 68. FN19. In Hunter, the expert discussed the band of confidence for the particular IQ test implemented and how applicant's mild depression and having been handcuffed at the time of taking an IQ test may have affected his score. Hunter, 243 S.W.3d at 670.

The evidence before us in this application does not demonstrate significantly subaverage intellectual functioning by applicant. Accordingly, we dismiss the application.

Hearn v. Cockrell, 73 Fed.Appx. 79 (5th Cir. 2003) (Habeas)

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas. (No. 3:01-CV-2551-D). Before HIGGINBOTHAM, SMITH, and CLEMENT, Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM:

Petitioner Yokamon Laneal Hearn (“Hearn”) seeks a Certificate of Appealability (“COA”) as to four issues: (1) whether the trial court violated Hearn's right to effective assistance of counsel under the Sixth Amendment by failing to appoint his defense counsel in the manner prescribed by Texas law; (2) whether the prosecutor violated Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 106 S.Ct. 1712, 90 L.Ed.2d 69 (1986), by using a peremptory challenge to prevent a black male from sitting on the jury; (3) whether the trial court violated his right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments and his right to due process under the Fourteenth Amendment by refusing to instruct the jury as to Hearn's parole eligibility; and (4) whether Dallas County violated Hearn's right to an impartial jury consisting of a cross-section of the community under the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments. Hearn's application for a COA is DENIED.

I. FACTS AND PROCEEDINGS

On March 25, 1998, Hearn and three accomplices drove to North Dallas with several firearms. At a coin-operated car wash, Hearn saw Joseph Franklin Meziere (“Meziere”) cleaning his car. With the assistance of his accomplices, Hearn abducted Meziere and stole his car. Shortly thereafter, Hearn killed Meziere by shooting him in the face. A jury convicted Hearn of capital murder, and the Texas state court entered a judgment imposing the death penalty. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Hearn's conviction on direct appeal. The U.S. Supreme Court denied Hearn's petition for a writ of certiorari.

Hearn filed an application for a writ of habeas corpus in the trial court, which issued findings of fact and conclusions of law and recommended that Hearn's application be denied. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals denied Hearn's application for state habeas corpus relief. The federal district court entered an order appointing counsel to represent Hearn for his federal habeas corpus petition, but ultimately denied his petition. The district court also denied Hearn's subsequent petition for COA, but granted his motion to proceed in forma pauperis on appeal.

II. STANDARD OF REVIEW

In deciding a request for a COA, we ask if a petitioner “has made a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right.” 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c)(2). Hearn need not “convince a judge, or, for that matter, three judges, that he ... would prevail,” but “must demonstrate that reasonable jurists would find the district court's assessment of the constitutional claims debatable or wrong.” Miller-El v. Cockrell, 537 U.S. 322, 123 S.Ct. 1029, 1038-40, 154 L.Ed.2d 931 (2003). When considering a request for a COA, “the question is the debatability of the underlying constitutional claim, not the resolution of that debate.” Id. at 1042.

III. DISCUSSION

A. Ineffective Assistance of Counsel

Hearn does not argue that the performance of his trial counsel was deficient in one respect or another. Instead, Hearn asserts that the procedure by which his trial counsel was appointed was defective. In particular, the trial court did not adhere to the procedure established by Texas law for the appointment of trial counsel in death penalty cases. The question for this Court is whether the failure to follow the proper administrative procedure signifies that Hearn received ineffective assistance of counsel at trial.

Under Texas law, each administrative judge in each administrative judicial region must form a selection committee composed of himself, one or more district judges, a representative from the local bar association, and one or more practitioners who are certified by the Texas State Bar in criminal law. Tex.Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 26.052. The selection committee is responsible for adopting standards governing the qualification of attorneys for appointment to death penalty cases. Id. These standards must be posted in each district clerk's office in the region with a list of attorneys qualified for appointment. Id. Based on this list, the presiding judge of the district court in which a capital felony case is filed appoints counsel for the indigent defendant. Id.

Apparently, this entire procedure was ignored in Dallas County. No selection committee was ever formed, no list was created, and no appointments were made on the basis of such a list. Instead, the administrative judge for the region encompassing Dallas County signed an order establishing general standards for the appointment of death penalty counsel. The order delegated the responsibility for selecting death penalty counsel to the trial courts, which were required to post their standards for appointment and list the qualifying attorneys. However, the trial court in this case never established any such standards or list.

In sum, the statutory procedure was not followed, and neither was the alternative procedure established by order of the administrative judge. The failure of the Texas courts to follow proper administrative procedure in appointing death penalty counsel is inexplicable. However, Hearn has not provided any evidence that this error deprived him of effective assistance of counsel.

To prevail on a constitutional claim of ineffective assistance of counsel, a defendant must show that counsel's performance was deficient and that the deficient performance prejudiced the defense. Procter v. Butler, 831 F.2d 1251, 1255 (5th Cir.1987) (citing Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 687, 104 S.Ct. 2052, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984)). “Unless a defendant makes both showings, it cannot be said that the conviction resulted from a breakdown in the adversary process that renders the result unreliable.” Strickland, 466 U.S. at 687. By failing to provide any evidence of deficient performance by his trial counsel, Hearn fails to satisfy the first element of the Strickland test.

Hearn also fails to satisfy the second element of the Strickland test because he suffered no prejudice from the alleged procedural error. As the Supreme Court recognized, it is “virtually inevitable” that courts will commit at least some errors during the course of a trial. Rose v. Clark, 478 U.S. 570, 577, 106 S.Ct. 3101, 92 L.Ed.2d 460 (1986); Delaware v. Van Arsdall, 475 U.S. 673, 681, 106 S.Ct. 1431, 89 L.Ed.2d 674 (1986) (holding that “the Constitution entitles a criminal defendant to a fair trial, not a perfect one”). These errors are not all equally significant, so it is necessary to distinguish between “trial errors” and “structural errors”. Clark, 478 U.S. at 576-79; Arizona v. Fulminante, 499 U.S. 279, 307-12, 111 S.Ct. 1246, 113 L.Ed.2d 302 (1991).

Trial errors, which may include constitutional errors, are analyzed under the harmless error standard. Clark, 478 U.S. at 576-77; Fulminante, 499 U.S. at 307-08. As long as the defendant had counsel and was tried by an impartial adjudicator, there is a strong presumption that any other errors that may have occurred are trial errors and thus subject to harmless-error analysis. Clark, 478 U.S. at 579. Structural errors “affect[ ] the framework within which the trial proceeds.” Fulminante, 499 U.S. at 310. Unlike trial errors, structural errors involve the violation of “basic [constitutional] protections, [without which] a criminal trial cannot reliably serve its function as a vehicle for determination of guilt or innocence, and no criminal punishment may be regarded as fundamentally fair.” Id. For this reason, structural errors may not be analyzed under a harmless error standard. Id. at 309. Examples of structural errors include the introduction of coerced confessions, the complete denial of right to counsel, and adjudication by a biased judge. Clark, 478 U.S. at 577-78.

Hearn had counsel and an impartial adjudicator, thus there is a strong presumption that any other errors are trial errors and thus subject to harmless-error analysis. Clark, 478 U.S. at 579. The procedural error alleged by Hearn does not amount to a structural error. Id. at 577-78; Fulminante, 499 U.S. at 306-07. Hearn fails to present any evidence that the procedural error had any effect on his trial or its outcome; therefore, we hold the error to be harmless. Wright v. State, 28 S.W.3d 526, 530-31 (Tex.Crim.App.2000) (holding that failure of trial court to follow administrative procedure for appointment of trial counsel in death penalty cases was harmless where defendant failed to object to noncompliance at trial and failed to present any evidence that he was harmed by the noncompliance).

B. Peremptory Challenge to Juror Brown

The prosecutor used a peremptory challenge to prevent Glenn Brown (“Brown”),a black male, from sitting on the jury. Hearn challenged the use of the peremptory challenge based on Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 89, 106 S.Ct. 1712, 90 L.Ed.2d 69 (1986), in which the Supreme Court prohibited prosecutors from using peremptory challenges to exclude jurors from participation in the jury based on their race. The prosecutor explained that he used the peremptory challenge based on Brown's religious beliefs and not his race. Specifically, the prosecutor feared that Brown's willingness to forgive his own grandmother's murderer signified that Brown would have a “real, real tough time” imposing the death penalty on Hearn. The trial court accepted the prosecutor's reasons for peremptorily striking Brown to be race neutral.

After the defendant has made a prima facie showing that the prosecutor exercised a peremptory challenge on the basis of race and the prosecutor has provided a race-neutral reason for striking the juror, the decisive question [is] whether [the prosecutor's] race-neutral explanation [ ] should be believed. There will seldom be much evidence bearing on that issue, and the best evidence often will be the demeanor of the attorney who exercises the challenge. As with the state of mind of a juror, evaluation of the prosecutor's state of mind based on demeanor and credibility lies peculiarly within a trial judge's province. Hernandez v. New York, 500 U.S. 352, 358-59, 365, 111 S.Ct. 1859, 114 L.Ed.2d 395 (1991). For this reason, the trial court's finding of fact on this question is entitled to great deference by this Court. Id. at 364-65. “[I]n the absence of exceptional circumstances, we would defer to state-court factual findings, even when those findings relate to a constitutional issue.” Id. at 366. Hearn offers no evidence of exceptional circumstances, thus this Court must defer to the judgment of the trial court.

C. Instruction on Hearn's Parole Eligibility

Before the start of trial, Hearn asked the trial court to include the following jury instruction: Regarding the law of parole, you are instructed that a prisoner under sentence of death is not eligible for parole. A prisoner serving a life sentence for a capital felony is not eligible for release on parole until the actual calendar time the prisoner has served without consideration of good conduct time, equals 40 calendar years.

Prior to closing argument, the trial court denied Hearn's request to include this instruction in the jury charge. According to Hearn, the trial court should have informed the jury, which had to consider whether he would pose a future danger to society, that he would not be eligible for parole for 40 years if he was not sentenced to death. In support of his argument, Hearn relies primarily on Simmons v. South Carolina, 512 U.S. 154, 163-64, 114 S.Ct. 2187, 129 L.Ed.2d 133 (1994), in which the Supreme Court held that [i]n assessing future dangerousness, the actual duration of the defendant's prison sentence is indisputably relevant. Holding all other factors constant, it is entirely reasonable for a sentencing jury to view a defendant who is eligible for parole as a greater threat to society than a defendant who is not. Indeed, there may be no greater assurance of a defendant's future nondangerousness to the public than the fact that he never will be released on parole. The trial court's refusal to apprise the jury of information so crucial to its sentencing determination ... cannot be reconciled with our well-established precedents interpreting the Due Process Clause. In Ramdass v. Angelone, 530 U.S. 156, 166, 120 S.Ct. 2113, 147 L.Ed.2d 125 (2000), a four-justice plurality of the Supreme Court held that “[t]he parole-ineligibility instruction is required only when, assuming the jury fixes the sentence at life, the defendant is ineligible for parole under state law.” Ramdass v. Angelone, 530 U.S. 156, 166, 120 S.Ct. 2113, 147 L.Ed.2d 125 (2000). In a concurring opinion, Justice O'Connor wrote: “ Simmons entitles the defendant to inform the capital sentencing jury that he is parole ineligible where the only alternative sentence to death is life without the possibility of parole.” Id. at 181 (O'Connor, J., concurring). Taken together, the plurality and concurring opinions in Ramdass indicate that the Simmons parole eligibility instruction is only required when the only alternative sentence to the death penalty is life without parole. As Hearn concedes, Texas does not provide for the possibility of life without parole. If he had not been sentenced to death, Hearn would have been eligible for parole in 40 years. Therefore, the trial court did not err in denying the jury instruction requested by Hearn, for he had no right to a Simmons instruction.

Alternatively, to hold that Hearn was entitled to a parole eligibility jury instruction, this Court would have to announce a new rule of constitutional procedure. Id. at 166, 181. Under Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. 288, 309-10, 109 S.Ct. 1060, 103 L.Ed.2d 334 (1989), this Court may not announce new rules of constitutional procedure on collateral review. Therefore, Hearn's claim as to the parole eligibility jury instruction is Teague-barred.

D. Representative Venire

Hearn argues that his constitutional rights to an impartial jury and to a venire consisting of a representative cross-section of the community were violated by the Dallas County jury system. Apparently, Dallas County pays jurors only five dollars per day, which results in Hispanics, persons 18 to 34 years old, and persons from households with incomes under $35,000 being underrepresented in venires and juries. Hearn cites Taylor v. Louisiana in support of his argument. 419 U.S. 522, 538, 95 S.Ct. 692, 42 L.Ed.2d 690 (1975) (holding that the “venires from which juries are drawn must not systematically exclude distinctive groups in the community and thereby fail to be reasonably representative thereof”).

Hearn's argument fails on its face. As the Supreme Court noted, the issue in Taylor was the constitutionality of “Art. VII, § 41, of the Louisiana Constitution, and Art. 402 of the Louisiana Code of Criminal Procedure [, which] provided that a woman should not be selected for jury service unless she had previously filed a written declaration of her desire to be subject to jury service.” Id. at 523. There is no comparable constitutional or legal provision in this case which explicitly provides for the exclusion of a distinctive group. Instead, Hearn complains that the low daily fee paid to jurors by Dallas County results in the underrepresentation of three groups, which are distinguished based on their ethnicity, age, and income.

The Supreme Court held that “venires from which juries are drawn must not systematically exclude distinctive groups in the community and thereby fail to be reasonably representative thereof.” Id. at 538 (emphasis added). In Taylor, there was clear evidence of a systematic effort to exclude women, but there is no such evidence here. Louisiana explicitly designed its system to exclude women, but the underrepresentation Hearn complains of is an indirect consequence of the low daily fee paid to jurors in Dallas County. Defendants are not entitled to a jury, jury wheel, pool of names, panel, or venire of any particular composition, and there is no requirement that those bodies “mirror the community and reflect the various distinctive groups in the population.” Id. For this reason, the underrepresentation alleged by Hearn is not unconstitutional.

IV. CONCLUSION

Hearn has not made a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right. Although he does not need to show he would prevail, Hearn must demonstrate that reasonable jurists would find his constitutional claims debatable. The constitutional claims presented by Hearn are not debatable. Therefore, Hearn's application for a COA is DENIED.