60th murderer executed in U.S. in 2001

743rd murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

3rd murderer executed in Georgia in 2001

26th murderer executed in Georgia since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

|

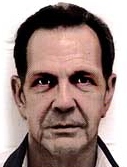

Fred Marion Gilreath, Jr. W / M / 41 - 63 |

Linda Gilreath W / F / 28 Gerrit Van Leeuwen W / M / 57 |

Father-in-law |

Summary:

Fred Gilreath was convicted of killing his wife, Linda Gilreath, and her father, Gerrit Van Leeuwen, in 1979. Linda and Fred Gilreath had been married for 11 years, but Linda had moved out a few days before the killings, after an argument. On May 11, 1979, she and her father came to the house to pick up some of her belongings. Both were shot dead.

On May 11, 1979, Dempsey Wolfenbarger went to the police station and told an officer that he was concerned about the safety of his stepdaughter, Linda Gilreath. He explained that Linda was in the process of obtaining a divorce from her husband, Fred Marion Gilreath, Jr. Linda's father, Gerrit Van Leeuwen, had gone to Linda's home to get her and her personal belongings, and neither had been seen since. Police went to the home and discovered Linda Gilreath's body in the house with a towel covering her face near a suitcase. Linda had been shot five times along her right side with a .30-30 lever action rifle from approximately two to three feet, and she had been shot in the face from approximately five to six feet away with a .12 gauge shotgun. The body of her father, Gerrit Van Leeuwen, was lying a short distance away with a .30-30 wound to his right thigh, a shotgun wound to his left chest, and two .22 caliber wounds to his head. Gasoline had been poured on and around the victims as well as on the kitchen floor. Gilreath was located at his brothers home in North Carolina, where he had arrived driving Linda's car intoxicated and took a shower with his clothes on. Gilreath testified at trial that he did not kill anyone and had intended to return to the house after going to the liquor store, but drove to North Carolina instead. During the guilt phase of trial, Petitioner instructed trial counsel to present no mitigating evidence at sentencing.

Citations:

Gilreath v. State, 279 S.E.2d 650 (Ga. 1981 (Direct Appeal).

Gilreath v. Taylor, 285 S.E.2d 187 (Ga. 1981) (Affirmed).

Gilreath v. Georgia, 102 S.Ct. 2258 (1982) (Cert. Denied).

Gilreath v. State Bd. of Pardons and Paroles, 2001 WL 1471657 (11th Cir. 2001) (Stay).

Gilreath v. Head, 234 F.3d 547 (11th Cir. 2000) (Habeas).

Internet Sources:

Georgia Department of Corrections

Death Warrant for Fred Marion GilreathAtlanta - A Cobb County Superior Court judge has signed a new death warrant for death row inmate Fred Marion Gilreath, Jr., 63. As a result, Corrections Commissioner Jim Wetherington has set the execution by lethal injection to occur at 7 p.m. on Tuesday, November 13, 2001, at the Georgia Diagnostic & Classification Prison in Jackson. Georgia now has execution dates set for three condemned inmates, including today's scheduled lethal injection for Terry Mincey, 41. Next is Jose High whose execution has been scheduled for 7 p.m. on November 6, 2001. High, 43, was sentenced to death for the murder for an 11 year-old Taliaferro County boy during a convenience store armed robbery. Gilreath, 63, was sentenced to death in 1980 for the 1979 murders of his estranged wife and father-in-law.

Georgia Department of Corrections

November 15th, 2001 - Gilreath Execution Rescheduled for 3:00 p.m. Today.Jackson - The execution of Fred Marion Gilreath Jr., 63, has been rescheduled for 3:00 p.m. today pending further instruction from the court. Gilreath, who was originally scheduled to be executed November 14th at 7:00 p.m., was given a stay by the U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals until 3:00 p.m. today. The execution will proceed once the stay is lifted.

On May 11, 1979, Dempsey Wolfenbarger went to the police station and told an officer that he was concerned about the safety of his stepdaughter, Linda Gilreath. He explained that Linda was in the process of obtaining a divorce from her husband, Fred Marion Gilreath, Jr., and that several days previously she had left her home to stay with her mother and Dempsey. Linda's mom had told her husband that Linda's father, Gerrit Van Leeuwen, had come to her home, where Linda was staying, about 12:30 p.m. on May 11th. He came to get Linda to come home, to talk to her husband, and pick up her personal belongings. Linda and her father left for the Gilreath residence at about 1:30 p.m. It takes about ten minutes driving time to reach the Gilreath home from the Wolfenbarger home. Linda said she'd be back in time to pick her stepfather up at work at 3:30 p.m. About 2:30 p.m., Linda's mom began phoning the Gilreath home but got no answer. She asked a friend, to pick her husband up at work. The friend passed the Gilreath residence coming and going; she told the Wolfenbargers that she saw Fred Gilreath's red truck and Linda's father's gold Volkswagen in the driveway, but she did not see Linda's blue Plymouth Duster.

Once he arrived home, Dempsey's wife called Linda's attorney for advice. He suggested that the Wolfenbargers go over to the house but Dempsey decided instead to go to the police station. He told the officer that he feared there might be "domestic trouble", and that Fred Gilreath had threatened Linda's life as well as the lives of the Wolfenbargers, and had threatened to burn the Wolfenbargers' trailer. Dempsey also told police his tires had been slashed and he believed Gilreath had done it. He said that Linda was driving a blue Plymouth Duster and Gilreath drove a red truck.

After hearing Dempsey's concerns, the officer radioed for a back-up unit; and the two police officers arrived at the Gilreath residence at approximately 5:00 p.m. The blue Duster was not in sight. They knocked on the front door; no one answered. They then knocked at the side door to a screened-in porch; no one answered. One of the officers peered into the enclosed garage looking for the Duster. He rejoined the other officer by the side screened porch and they observed that both the porch door and the sliding glass door inside the porch were ajar, that the sound of music could be heard, and that a strong odor of gasoline permeated the area. The two officers then entered the screened porch (which was described as looking like an enclosed carport) and looked through the sliding glass door. From that vantage point, they saw a man's body. One of the officers then stepped inside the glass door and saw Linda's body. The two officers could see large puddles of gasoline in the kitchen and toward the living room; they also saw a shotgun and a shell lying on the floor. They then checked the other rooms of the house looking for the Gilreaths' two children. Finding no one, the officers called the detectives, secured the crime scene after they opened the front door to disperse the gas fumes and went outside to await the detectives.

Dempsey arrived shortly after Davis and Rogers discovered the bodies but was not allowed to enter the house. Dempsey had told police that the Gilreaths had two children. The officers were not aware that Linda Gilreath had taken the children to Seneca, South Carolina, the day before to stay with Linda's sister.

Detectives arrived at about 5:33 p.m. They walked through the house, interviewed Dempsey Wolfenbarger, and then reentered the house to complete the investigation, i.e., locate evidence, take measurements and make drawings. A detective testified at trial that upon checking he discerned no signs of forcible entry into the house. He found a green army-type gas can sitting by the door to the screened porch. He entered through the sliding glass doors and found Linda Gilreath's body lying between a coffee table and a love seat in the living room; a pink towel covered her face and a white medium-sized suitcase sat by the end table. The evidence showed that Linda had been shot five times along her right side with a .30-30 lever action rifle from approximately two to three feet away. She had been shot in the face from approximately five to six feet away with a .12 gauge shotgun. Gerrit Van Leeuwen was lying a short distance away; he had sustained a .30-30 wound to his right thigh, a shotgun wound to his left chest, and two .22 caliber wounds to his head. Gasoline had been poured on and around the victims as well as on the kitchen floor. Police seized numerous items which were in plain view, among them a .22 caliber short shell casing, six .30-30 caliber shell casings, two shotgun shell casings, a .22 caliber rifle and a .12 gauge shotgun. Two days later they returned with a search warrant and recovered another .22 caliber shell casing.

Prior to diagramming the crime scene, police had placed a southeastern regional lookout on Fred Gilreath and on the blue Duster. Upon receiving the message, the dispatcher for the sheriff's department in Hendersonville, North Carolina, contacted Mike Gilreath who lived and worked in Hendersonville, told him about the message, and asked him to let the sheriff's department know if he saw or heard from his brother Fred. Fred Gilreath arrived at his brother's office, driving the blue Duster, at approximately 7:30 p.m. Mike Gilreath immediately asked one of his business associates to go tell the sheriff that his brother had arrived. By the time officers arrived, Fred Gilreath had showered with his clothes on and was wearing only his still wet cut-off shorts. A forensic serologist from the State Crime Laboratory testified that she examined Gilreath's shorts and found a stain which could have been blood. Because the sample was inadequate, it could not be positively identified. The officers arrested him, explaining that he was wanted for questioning in relation to a double homicide in Georgia; Gilreath asked if he could call his wife.

Cobb County police arrived in Hendersonville the next day. Pursuant to a warrant they searched the Duster and a partial box of .22 caliber short ammunition was recovered. The shotgun and the .22 caliber rifle which were found at the scene were identified as the murder weapons by a firearms examiner from the State Crime Laboratory. The Gilreaths' next door neighbor testified that he heard muffled gunshots coming from the direction of the Gilreaths' home between 1:30 p.m. and 2:40 p.m. on May 11. He paid little attention to them because it was not uncommon to hear gunshots in the neighborhood. This neighbor also reported having seen water in the street. When police contacted the Cobb County Water Department they found three workmen who had bled a water hydrant directly across the street from the Gilreath residence on May 11th. The workmen had arrived at approximately 1:30 p.m. and left at approximately 1:50 p.m. One workman testified he heard five rapid-fire shots from what sounded like a high-powered rifle emanate from the Gilreath residence. He also testified that he was busy doing paperwork and didn't see anyone. Another of the workmen testified that he saw a Volkswagen and a van or truck in back of the garage at the Gilreath residence when he arrived. After he arrived, he noticed that a blue car, probably a Dodge, had driven up and parked in the driveway. Because he was getting something from the truck, he did not see the blue car arrive. After the blue car arrived, he saw an old man walk around the house, come back, and go back around the house. He then heard the five shots and did not see the old man again. Shortly thereafter the water crew left; the blue car was still there. The third workman testified that he saw a dark blue over light blue Duster drive up and saw two people get out. One of the two (the passenger) was an elderly man. He saw the elderly man walking around the yard; about a minute after the elderly man disappeared behind the house, he heard the five shots. The worker was unable to say whether the driver of the blue Duster was a man or a woman. He did testify that at the time he heard the shots there were four cars at the Gilreath residence: the blue Duster, a gold Volkswagen, an old red pickup truck, and another old car on blocks. The neighbor was able to fix the time because he arrived at home about 1:30 and his stepson came home from school at 2:30 or 2:40. He knew the shots occurred in the interim.

Fred Gilreath testified in his own defense. He stated that he was home on May 11th with his father-in-law. His father-in-law left about 11:30 to go to his ex-wife's home. He was downstairs in his father-in-law's apartment when he heard his wife and her father come in. He heard his wife in the bedroom; he went upstairs and started out the door, telling his father-in-law he'd be back in a few minutes. His father-in-law said "Linda's here and she wants to talk to you" but Gilreath responded, "Gary, I told you I am not ready to talk to Linda. I don't want to talk to her until I get back from North Carolina." He then left in the blue Duster at 1:25 p.m., intending to go to the liquor store and come back. He had had two drinks of rum while alone at the house. At the liquor store he bought a beer and a fifth of vodka. He mixed the two and while drinking decided to go on to Hendersonville. He was wearing cut-off shorts, a tee shirt, a terry cloth hat and sandals. He continued drinking and was sick as he crossed a bridge connecting South and North Carolina. When he reached Hendersonville, he tried to rent a motel room but the clerk refused to give him a room because he was drunk so he went on to his brother's office. When he told his brother he needed to go take a shower to sober up, his brother told him there was a shower in the office. He took off his sandals and hat and put them on an end of the tub because there was nowhere else to put them; his shorts he hung on the one hook available. When he finished showering he discovered his brother had no towels so he put his shorts back on although he was wet, thus accounting for his clothes being wet. Gilreath identified the .22 caliber rifle and the shotgun as his, as well as the gas can which he said he used for the lawn mower. He denied having killed his wife or his father-in-law. The jury found Gilreath guilty of both murders and sentenced him to death for each.

UPDATE: A federal appeals court Wednesday night delayed the execution of convicted killer Fred Marion Gilreath Jr. by one day while it considered an appeal. The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals did not immediately say why it delayed the execution until at least 3 p.m. on Thursday. State officials, who had originally scheduled the execution for 7 p.m. Wednesday, rescheduled it for 7 p.m. Thursday. Earlier, U.S. District Judge J. Owen Forrester had granted a two-hour stay for Fred Gilreath, pushing to 9 p.m. the time he was scheduled to be put to death at the state prison here. The judge wanted to give the convicted man's lawyers time to make their case that the state Board of Pardons and Paroles cannot make a decision on whether to commute Gilreath's death sentence. He finally rejected their arguments.

Fred Gilreath's lawyers had argued that board member Gene Walker -- who voted on the commutation request Tuesday despite being at a conference in Las Vegas not related to the Board's business -- should have been at the hearing. The lawyers also argued that the Parole Board has a conflict of interest in making a decision, because commuting Fred Gilreath's death sentence would go against the office investigating two of the Parole Board's members. The Attorney General's office is investigating allegations that Board Chairman Walter Ray and member Bobby Whitworth lobbied for a change in state law that would benefit a private company that had hired them as consultants. On Tuesday, the Board of Pardons and Paroles refused to save Fred Gilreath from his scheduled execution for killing his wife and father-in-law, despite pleas from the relatives of the victims of a domestic dispute spawned by anger over a pending divorce.

Fred Gilreath, 63, was sentenced to death for shooting Linda Gilreath and her father, Gerritt Van Leeuwen, in 1979 when the two returned to her Cobb County home to collect her clothes. "If my mother could talk now, she would say she didn't want him to die," said Christopher Kellett, who was age 8 when his father shot his mother. "We've lost enough. ... We don't want to lose any more." Christopher Kellett reconciled with his father a year ago and has since introduced his children to their grandfather. Christopher Kellett said the Board of Pardons and Paroles meeting was "very emotional." Christopher Kellett, his sister and aunt -- sister to one victim and daughter of the other -- spent 90 minutes with the Board, pleading that the members spare Fred Gilreath, who would be the third person to die by lethal injection in Georgia in less than three weeks. Cobb County District Attorney Pat Head, who was not in office when Fred Gilreath was prosecuted, met with four members of the Board later in the day -- one individually and then three members later in the afternoon -- to encourage them to deny the request for clemency. Board member Gene Walker was in Las Vegas, where he was attending a conference unrelated to Board of Pardons and Paroles business. Cobb County District Attorney Pat Head said he told Board members, "I believe this case was an appropriate case for the death penalty." He said victims' wishes should not dictate the punishment. "We are a society of laws, and if we allow emotions to dictate decisions ... we put society at risk," District Attorney Pat Head said after his meetings with the Board. "This was a brutal murder." In the past, all five Board members have been present for commutation hearings, but Board member Gene Walker said Tuesday the trip to Las Vegas had been planned for a long time. The vote is secret, but at least three votes are needed to commute a sentence. While not saying how he voted, Board member Gene Walker said he made his decision based on a review of Fred Gilreath's file and Board staff members' reports of the meetings on Tuesday with Fred Gilreath's supporters and the prosecutor. "This is not a typical domestic dispute to me," Gene Walker said. "This goes far beyond that. This is a man who murdered his wife and his wife's father. And he shot them multiple times and at different locations [in the house]. I have to assess all that. Clearly, I feel comfortable with where I am and what I'm doing."

Office of the Georgia Attorney General

PRESS ADVISORY

Friday, November 16, 2001

Information on the Execution of Fred Marion Gilreath, Jr.

Georgia Attorney General Thurbert E. Baker offers the following information on the execution of Fred Marion Gilreath, Jr.. Execution On October 24, 2001, the Superior Court of Cobb County filed an execution order, setting the seven-day window in which the execution of Fred Marion Gilreath, Jr., might occur to begin at 12:00pm on November 13, 2001 and end at 12:00pm on November 20, 2001. The Commissioner of the Department of Corrections scheduled the execution to occur at 7:00pm on November 14, 2001. On November 14, 2001, while considering a Motion for Stay and Temporary Restraining Order arising out of the State Board of Pardons and Paroles’ denial of Gilreath’s application for clemency, the United State District Court for the Northern District of Georgia granted a stay of execution to consider Gilreath’s motions until 9:00pm on November 14, 2001. Following the District Court’s denial of the Motion for Stay and Temporary Restraining Order, Gilreath appealed to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals. The Court of Appeals issued a stay of execution until 3:00pm on November 15, 2001 during their consideration of Gilreath’s appeal. On November 15, 2001, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals denied Gilreath’s appeal. The Commissioner of the Department of Corrections scheduled Gilreath’s execution to take place at or after 3:01pm on November 15, 2001. The scheduled execution of Gilreath was carried out at approximately 3:53pm on Thursday, November 15, 2001.

Gilreath’s Crimes Gilreath was sentenced to death for the murders of his wife, Linda Gilreath, and his father-in-law, Gerrit Van Leeuwen, on or about May 11, 1979. Linda Gilreath’s stepfather went to Cobb County police on the afternoon of May 11, 1979, with his concern for the safety of his stepdaughter as she was supposed to have picked him up from work that afternoon but did not show up. Linda Gilreath was in the process of obtaining a divorce from Fred Gilreath and had been staying with her mother. Gilreath had threatened Linda’s life, as well as the life of both her mother and stepfather, and he had threatened to burn down their trailer. Earlier that day, Linda Gilreath had gone with her father to the Gilreath home for some personal items. Linda Gilreath was driving a blue Plymouth Duster that day, while Fred Gilreath ordinarily drove a red truck. Two officers went to the Gilreath residence at approximately 5 p.m. No blue Duster was in sight. Police knocked on the front door and a side door to a screened-in porch but received no answer. Officers saw that a porch door and the sliding glass door inside the screened-in porch were ajar, through which they could hear music and smell gasoline. From that point one officer saw a man’s body inside the house; when the officer stepped inside the porch, he saw the body of Linda Gilreath.

Gasoline had been poured on and around the two bodies, and puddles of gasoline were on the floor near the living room and in the kitchen. A shotgun and a shell were lying on the floor. No signs of forcible entry were found. A green military-type gas can was sitting by the door to the screened-in porch. Linda Gilreath’s body was found in the living room lying between a coffee table and a love seat, her face covered by a pink towel. A suitcase was near the end table. Linda Gilreath had been shot five times on her right side with a .30-.30 rifle and shot once in the face with a .12 gauge shotgun. Matter was splattered across the love seat, the carpet and walls. Her father, Gerritt Van Leeuwen, was on the floor nearby and had been shot with three different guns. He had been shot in his right thigh with a .30-.30 rifle, shot in the chest with a shotgun, and shot in the head twice with a .22 caliber weapon. Police found a .22 rifle and a .12 gauge shotgun at the scene. Police also collected shell casings from a shotgun and from .22 and .30-.30 caliber weapons.

Police placed a lookout for Gilreath and the blue Duster. A dispatcher in Hendersonville, North Carolina, contacted Gilreath’s brother who lived nearby and asked the brother to let police know if Gilreath showed up. At approximately 7:30 p.m. that evening, Fred Gilreath came to his brother’s office driving a blue Duster. When police arrived at the office around 8 p.m. in response to the brother’s call, they found Fred Gilreath, who had showered with his clothes on, still wearing his wet cutoffs. Police arrested Gilreath and told him they wanted to question him about a double homicide. In response he asked to call his wife. A Cobb County detective arrived in North Carolina the next day and found part of a box of .22 caliber bullets in the Duster. He went to a cabin that belonged to Fred Gilreath and found some empty shotgun shell cases, .30/.30 caliber cases and .22 caliber cases lying in the drive. The shotgun and the .22 rifle found at the crime scene were identified as the murder weapons. The firearms examiner also determined that the same .30-.30 gun used to shoot the victims had fired the empty shells found at the North Carolina cabin.

Between 1:30 p.m. and 2:40 p.m. on the afternoon of May 11, the Gilreaths’ next-door neighbor heard muffled gunshots from the direction of the Gilreath home. Three workmen from the Cobb County Water Department were working in the area across from the Gilreath residence that same afternoon between 1:30 p.m. and 1:50 p.m. One workman heard five shots in rapid succession from the Gilreath home but did not see anyone because he was doing paperwork. Another workman had seen a Volkswagen and a truck at the Gilreath residence when the work crew arrived and later noticed a blue car had arrived and parked in the driveway. He then saw an old man walk around the house, heard five shots and did not see the man again. A third employee saw a blue Duster arrive with two people in it, one of whom was an elderly man. After the elderly man went behind the house, the employee heard five shots. When the work crew left, the blue car was still there, as well as the red truck. Gilreath testified at trial he had spoken with his father-in-law after he and Linda Gilreath came to the house that day and told the father-in-law he was not ready to speak with his wife until he returned from North Carolina, left in the blue Duster around 1:25 p.m., and bought beer and a fifth of liquor which he drank while he drove to North Carolina. He admitted taking a shower at his brother’s office to sober up. He admitted the .22 caliber rifle, the shotgun and the gas can were his. Gilreath denied killing his wife and father-in-law.

The Trial - At a jury trial which began on February 25, 1980, in the Superior Court of Cobb County, Gilreath was convicted of the malice murders of his wife and father-in-law and sentenced to death for both murders on March 3, 1980. The jury found three O.C.G.A. § 17-10-30 statutory aggravating circumstances to support the two death sentences: each murder was outrageously vile and wantonly vile, horrible and inhuman in that it involved torture, depravity of mind and aggravated battery, § 17-10-30(b)(7); and the murder of Gerrit Van Leeuwen was committed while the offender was engaged in the murder of Linda Gilreath, § 17-10-30(b)(2). The convictions and sentences were affirmed on direct appeal. Gilreath v. State, 247 Ga. 814, 279 S.E.2d 650 (1981), cert. denied, 456 U.S. 984, reh’g denied, 458 U.S. 1116 (1982).

The First State Habeas Corpus Case - In 1983 Gilreath filed his first state habeas corpus petition in the Superior Court of Butts County, alleging constitutional errors occurred at his trial which should cause his convictions and sentences to be set aside. Pursuant to an evidentiary hearing, the state habeas corpus court denied relief on April 23, 1986, in an unpublished order. The Georgia Supreme Court denied Gilreath’s application for certificate of probable cause to appeal that order. The United States Supreme Court declined to review the state habeas corpus court’s decision. Gilreath v. Kemp, 479 U.S. 890, reh’g denied, 479 U.S. 999 (1986).

The First Federal Habeas Corpus Case - On January 8, 1987, Gilreath filed his first federal habeas corpus petition in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, Atlanta Division. That petition was ultimately dismissed without prejudice so that Gilreath could return to the state courts to litigate new claims.

The Second Sate Habeas Corpus Case - In August 1987 Gilreath filed a second state habeas corpus petition. That petition was denied on August 23, 1990. On March 1, 1991, the Georgia Supreme Court denied Gilreath’s application for a certificate of probable cause to appeal that ruling. The United States Supreme Court again denied review. Gilreath v. Zant, 502 U.S. 885, reh’g denied, 502 U.S. 1001 (1991).

The Second Fedeal Habeas Corpus Case - On September 23, 1992, Gilreath filed his second federal habeas corpus petition in the Northern District of Georgia. After additional factual development of claims, the district court denied relief on March 29, 1996. On March 7, 1997, the district court denied Gilreath’s motion to alter or amend the judgment and denied his request for reconsideration. On September 3, 1997, the district court granted Gilreath permission to appeal certain issues. Oral argument was had in the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit on April 29, 1998, and on December 15, 1999. On December 1, 2000, the three judge panel issued its opinion, affirming the district court’s denial of relief on all grounds. Gilreath v. Head, 234 F.3d 547 (11th Cir. 2000). Rehearing was denied on April 17, 2001. On October 1, 2001, the United States Supreme Court denied Gilreath’s petition for a writ of certiorari to review the Eleventh Circuit’s decision. The mandate of the Eleventh Circuit was issued on October 10, 2001, formally signaling the end of litigation in the second federal habeas case.

New Hampshire Coalition Against the Death Penalty

Ga., Texas Men Put to Death

JACKSON, Ga. (AP) - A man convicted of killing his wife and father-in-law in 1979 was executed Thursday, the third condemned inmate Georgia has put to death in three weeks.

The Georgia inmate, Fred Marion Gilreath Jr., 63, had received a one-day stay Wednesday for the U.S. Supreme Court to consider his attorney's arguments that his clemency hearing was unfair. The court denied the motion. In his final statement, Gilreath thanked his lawyers "for the good work they did for me, and for the men in blue, and the warden for treating me with respect, dignity and like a human being."

Gilreath's lawyers had contended the clemency hearing was unfair because one member of the five-person state Board of Pardons and Paroles was absent and some board members had conflicts of interest. Gilreath was convicted of killing his wife, Linda, and his father-in-law, Gerrit Van Leeuwen, in Cobb County in 1979. His family argued he should not be executed because the slayings arose from a heated domestic dispute. Gilreath was sentenced to death in 1980. The Georgia execution was the third since the state Supreme Court ruled last month that the electric chair was cruel and unusual punishment. All three condemned men were put to death by injection.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Fred Gilreath - Scheduled Execution Date and Time: 11/14/01 Time 7:00PM EDT.The pace of executions is on the increase in Georgia, in the wake of a Georgia Supreme Court ruling that, in effect, replaced the electric chair with death by lethal injection. In spite of an apparent victory at derailing electrocutions, Fred Gilreath is still set to die on November 13th.

Over twenty years ago, Fred Gilreath murdered two individuals, Linda Gilreath and Gerritt Van Leeuwen. Under the influence of alcohol and numerous mental health problems, Fred acted out in violence. However, a sentence of death, reserved for the most heinous and premeditated of murders, is questionable in Fred Gilreath’s case. Furthermore, at his trial Gilreath demanded that no mitigating evidence be presented in his defense during the sentencing phase. Such circumstances exist that, had they been presented at court, could have been used to spare Gilreath’s life. Stories of an abusive childhood, lifelong problems with alcohol, and a recurring incidence of mental health problems would have shed more light on the circumstances of this crime and Gilreath’s state of mind. A crime committed in the haze of alcoholism and mental illness is certainly different than premeditated murder

Even for those who support the death penalty, this case should be a questionable application of capital punishment. Please let the State of Georgia know that you oppose the circumvention of the law in Fred Gilreath’s case and capital punishment in general.

"A Dead Issue - Where does it say, "Kill for Jesus"?" by John Sugg.

It's too bad for Fred Gilreath that he didn't live in Yugoslavia. He'd still be alive. Just 10 days before Georgia officials at a state prison in Jackson jabbed needles into Gilreath and injected him with poison, the war-torn, ripped-apart nation of Yugoslavia decreed that it would no longer execute criminals. The Balkan republic joined almost the entire civilized world, 109 nations including all of Western Europe, in shunning state homicide. The United States hunkers down with the international Neanderthals -- human rights criminals such as China, Cuba, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and, if there any left, the Taliban mullahs -- in petulantly embracing legalized lethal savagery.

Gilreath spent a third of his 63 years awaiting the executioner's arrival -- in itself a gruesome form of punishment any sane society would declare cruel and unusual. The relatives of the Gilreath's victims, who also were the condemned prisoner's kin, didn't howl for his death. They pleaded and prayed for his life. Indeed, by any criteria imaginable, Gilreath was a poor choice for official slaughter.

On May 11, 1979, Fred Gilreath took a shotgun and two rifles and blew away his wife, Linda, and her father. The marriage was breaking up, Gilreath was tanked up, and what went down was bloody carnage. It was also a crime of passion, a status that while certainly not exonerating the killer, usually merits life imprisonment. The tragic couple had two children, Chris and Felicia. As one of Gilreath's lawyers, Brian Mendelsohn puts it: "When they were 8 and 12, they had one parent violently removed from their lives. Twenty-two years later, the state of Georgia subjected them to the same trauma all over again." Gilreath's son, Chris Kellett, talked to me after his dad's execution. "I had always been an advocate of the death penalty," he said. "But if this is how it is carried out ... I saw things that were horrible and incredible. I can't believe there isn't a higher power that doesn't stop this."

Kellett also noted that who gets the fatal needle is "arbitrary." The state Board of Pardons and Parole "certainly doesn't seem interested in studying the merits of cases and making an informed decision," he said. His words echo a 29-year-old U.S. Supreme Court decision, Furman v. Georgia, in which the death penalty was struck down, igniting a bloodlust race among states to reenact legal homicide. Justice Potter Stewart wrote in Furman that executions were "wantonly and ... freakishly imposed." Which pretty much describes what happened to Gilreath.

Mike Mears, the state-paid (but woefully underfunded) defender of the damned points out how mercurial capital punishment is in Georgia. "You kill someone in DeKalb County, you're likely to get executed. Do the same thing a few yards away in Fulton County, you'll get life. Now that's arbitrary." Any sense of fairness evaporated with Gilreath's execution. "I thought the death penalty was supposed to be for premeditated murder," Kellett said. "Yet, when we went before the board, the first question they asked was about premeditation. They obviously hadn't taken the time to read the information we had given them. We had addressed that point at length, and what my father did was not premeditated." Kellett thought for a moment, and then added: "But what the state did to him was the epitome of premeditation. They plotted his murder for more than 20 years."

If you should go to the website of the pardons board (www.pap.state.ga.us/overview.html Why did Fred Gilreath die?

I thought the state Board of Pardons and Parole, which turned thumbs down on Gilreath two days before his execution, might know. But according to Kellett and others who attended the hearing, the board members were uninterested in the merits of the case. One of the board members felt a junket to Las Vegas was more important than a man's life -- and somewhere between the slot machines and the showgirls, he faxed in his vote.

Of course, one shouldn't expect much of the board. It may well be a high-crime area, with two of its own members under investigation for ethical skullduggery. But being scummy in Georgia doesn't disqualify one from voting on life and death decisions.

If not the pardons officials, I mused, Gov. Roy Barnes should be able to supply a clear and convincing rationale for capital punishment.

His spokeswoman, Joselyn Butler, wasn't overjoyed at my inquiry. "He (Barnes) supports the death penalty," she said -- and the adverb "tersely" applies. "I don't know why. He's never explained."

Maybe I can help. It's really simple. One word:

Votes.

Georgians For Alternatives to the Death Penalty (Gilreath News)

Updated 11/16/01

Amnesty International - Urgent Action Appeal

Against the Victims' Family's Wishes, the State Killed Fred Gilreath on November 15, 2001.

USA (Georgia): Fred Marion Gilreath, aged 63

Fred Gilreath was executed in Georgia on 15 November after 21 years on death row. He was convicted of killing his wife, Linda Gilreath, and her father, Gerrit Van Leeuwen, in 1979.

The execution had been scheduled for 7pm on 14 November, but was delayed by 20 hours by a federal court. The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals issued the temporary stay apparently to give it more time to consider a last-minute appeal that his clemency hearing had been not been full, fair or impartial, due to the absence of one board member, and an alleged conflict of interest of two others. Early on 15 November, the 11th Circuit court refused any further stay. The US Supreme Court then delayed the execution by another 30 minutes. When it too, denied a further stay, the execution went ahead, and Fred Gilreath was pronounced dead at 3.53pm on 15 November.

The state Pardons and Paroles Board had rejected clemency on 13 November. It heard testimony supporting clemency from the family members of the victims and the prisoner (see original EXTRA). Fred Gilreath's son urged the Board to grant clemency: 'If my mother could talk now, she would say she didn't want him to die. We've lost enough... We don't want to lose any more'.

After the execution, a spokesperson for the US organization Murder Victims Families for Reconciliation said that the Gilreath family were devastated: 'The state of Georgia made orphans of [Fred Gilreath's children]... despite their pleas to the state of Georgia that their families not be traumatized. Another body is in the coffin'.

Fred Gilreath is the third person to be executed in Georgia in the past three weeks, and the 26th since the USA resumed executions in 1977. Nationwide his was the 743rd execution since 1977 and the 60th this year.

No further action by the UA Network is requested. Many thanks to all who sent appeals.

______________________________________________

Atlanta Journal-Constitution (November 16, 2001)

"Convicted Killer Fred Gilreath is Executed," by Rhonda Cook.

JACKSON - A 63-year-old grandfather was executed Thursday for killing his wife and her father in a drunken rage spawned by a pending divorce.

After two court stays -- one moving Fred Gilreath's execution from 7 p.m. Wednesday to 9 p.m. and a second putting it at 3 p.m. Thursday -- the U.S. Supreme Court delayed the execution 30 minutes so it could review his file. Gilreath was pronounced dead at 3:53 p.m. Thursday. His final words were to thank his lawyer, his family and friends as well as prison officials.

"My God has forgiven me for all my sins. I have forgiven the people who have done me wrong," Gilreath said just before a chaplain prayed over him and officials began the eight-minute process of executing him.

A Cobb County jury decided in 1980 that Gilreath should be executed for the shootings of his wife, Linda, and his father-in-law Gerritt Van Leeuwen. Fred Gilreath had been drinking when Linda Gilreath and Leeuwen came to the Gilreath's Cobb County home May 11, 1979, to collect some clothes. Linda Gilreath was planning to file for divorce later that day and had moved into her mother's house. Fred Gilreath shot Linda Gilreath five times and his father-in-law four times before dousing their bodies with gasoline and fleeing to a relative's home in another state.

Gilreath was the third man in three weeks to be executed in Georgia by lethal injection, which became the state's method of capital punishment once electrocution was found unconstitutional in early October.

Gilreath's two adult children waited outside the prison with other death penalty protestors. Gilreath's four young grandchildren, between the ages of 2 and 4, scampered on the prison grounds, batting a yellow tennis ball. Buzzards circled overhead.

Gilreath's daughter, Felicia Floyd, turned and hugged an anti-death penalty activist when she learned that the execution had begun. Her brother, Christopher Kellett, sat at a picnic table a few feet away with his head in his arms.

A spokesman for the family, Renny Cushing, executive director of Boston-based Murder Victims Families for Reconciliation, said after the execution that Gilreath's family was devastated.

"The state of Georgia made orphans of Felicia Floyd and Chris Kellett ... despite their pleas to the state of Georgia that their families not be traumatized. Anther body is in the coffin," he said.

When Gilreath's children realized the execution was complete, they were enveloped by about 20 people who hugged them.

The family was frustrated by confusion over the rescheduled time of Gilreath's execution. The Department of Corrections told the family he would be executed at 7 p.m. Thursday and did not correct this until the family arrived at the prison on Thursday, department spokesman Mike Light said. As a result, Gilreath's family missed one-fourth of their allotted time to visit with him today, getting an hour and a half to visit with him them instead of two.

It was "a painful meeting with the family," Cushing said. Gilreath's children had hoped to bring his grandchildren for a last visit, but because of the confusion over the scheduled execution time, they did not get the chance.

Gilreath's sister-in-law, Betty Newlin, who had also forgiven Gilreath for killing her sister and her father, stayed away from the prison to support her mother.

There were no major problems inserting the needles that carried the drugs as there were during last week's execution, when emergency medical technicians abandoned their attempts to insert needles into Jose High's arm after trying for 15 to 20 minutes. EMTs could find a vein in only one of Gilreath's arms, so they inserted one in the back of his left hand as a backup for the primary IV.

Gilreath's crime was unlike the crimes of the two men who preceded him on a gurney in the death chamber at the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison and unlike the offenses that landed one woman and 124 other men on Georgia's Death Row, his lawyers argued. They labeled Gilreath's offense a "domestic" killing, while others, they said, committed murders along with other felonies like rape, armed robbery or kidnapping or for money.

Also, the victims of the murdered in the Gilreath case also were the relatives of the condemned.

Floyd, Kellett and Newlin had unsuccessfully pleaded for mercy with the courts and the state Board of Pardons and Paroles, insisting that they had forgiven Gilreath and that their wishes as the victims, that he be spared, should be respected.

The request to the board held up Gilreath's execution. His lawyers argued that Gilreath did not receive a full and impartial hearing before the five-member panel.

They had two specific complaints:

Board member Gene Walker was not at what was described as an emotionally-charged, closed Parole Board meeting Tuesday when Gilreath's children pleaded for mercy for their father. Walker was attending a technology convention in Las Vegas, unrelated to his duties on the board. He said he decided on the commutation request based on Gilreath's file and a report of the meeting provided by the board's lawyer. According to testimony in a hearing Wednesday, Walker declined an offer to listen to a tape of the proceedings and sent his vote to deny Gilreath's request via fax.

Gilreath's lawyers also complained that two other board members faced a conflict of interest that might push them to support Gilreath's execution. Attorney General Thurbert Baker's office is investigating whether Chairman Walter Ray and board member Bobby Whitworth improperly took money from a state vendor. Gilreath's lawyers argued that Ray and Whitworth may try to curry favor with Baker, and influence the investigation against them, by voting against Gilreath's request. Baker's office also is responsible for defending any challenges to death sentences.

The board's vote on such requests, but the votes against commutation by Walker and one other member, Garfield Hammonds, were announced during testimony before a federal judge hearing Gilreath's challenge on Wednesday.

There are no other executions pending.

______________________________________________

Atlanta Journal-Constitution (11/15/01) By RHONDA COOK, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Staff Writer.

A federal appeals court late Wednesday gave Fred Gilreath another day to live, putting off his scheduled execution until 3 p.m. Thursday.

Without comment, the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals granted a temporary stay to Gilreath, the 63-year-old grandfather who was condemned to die for killing both his wife and her father in 1979.

The stay came little more than an hour after a lower court judge ended a five-hour hearing on Gilreath's claim that the state Board of Pardons and Paroles had not given him full, fair and impartial consideration on his request that his death sentence be commuted to life.

If he is executed, Gilreath will be the third person in three weeks to die by lethal injection in Georgia. A gurney and a needle replaced the state's electric chair when the Georgia Supreme Court determined in October that electrocution was unconstitutional.

Turning down Gilreath's request to stop his execution, U.S. District Court Judge J. Owen Forrester said he found "no due process violations at all" based on evidence presented in the hearing that ended just minutes before Gilreath's original time to die, 7 p.m.

Gilreath's lawyers had argued that he did not get fair consideration before the Parole Board on Tuesday because one member was absent and two others could not be impartial because they are under investigation by the state attorney general.

Gilreath was sentenced to die for killing his estranged wife, Linda, and her father. Gilreath had been drinking when his wife and Gerritt Van Leeuwen came to his Cobb County house to collect some clothes. Linda Gilreath was planning to file for divorce. Gilreath shot his wife five times and Leeuwen four times.

In their appeals, Gilreath's attorneys have claimed his case is unlike any other on Georgia's Death Row; Gilreath killed during a domestic dispute and the murder did not involve an armed robbery, kidnapping or rape.

They also point out that Gilreath's children and Linda Gilreath's family, also victims, say they forgive him and they don't want him executed.

Their pleas for mercy are the basis for the question now before the federal appeals court.

Gilreath's lawyers say the board, though it claims to give weight to the wishes of victims, did not give Gilreath's request for a commutation full and unbiased consideration.

They argued that because one board member, Gene Walker, was out of town on Tuesday, he missed the emotion of the 90-minute meeting with Gilreath's family and that might have swayed him.

Walker, in Las Vegas for a technology convention unrelated to board duties, said Tuesday he based his vote to deny Gilreath's request on documents in the board's file and on an account of the meeting with the relatives by the board's lawyer.

Gilreath's lawyers also said that two other board members may have been swayed to vote against Gilreath's commutation request because they want to curry favor with the Attorney General's Office, which is investigating them to determine if they improperly took money from a state vendor. The lawyers with the AG's office also argue against Gilreath's appeals.

Gilreath's attorney, Thomas Dunn, argued that Board Chairman Walter Ray and member Bobby Whitworth have a conflict of interest. Dunn also said Ray's and Whitworth's anxiety over the investigation may be felt by the other three board members and they might also be inclined to vote in a way that would please Attorney General Thurbert Baker. "The investigation of two ... members does taint the board," Dunn argued before Forrester.

Garfield Hammonds testified Wednesday said he had taken little notice of the investigation. He said he voted against saving Gilreath because the details of his case supported his death sentence.

______________________________________________

"Pardons and Paroles Board Rejects Clemency; Gilreath Can Now Turn Only to Courts," by Rhonda Cook. (Atlanta Journal-Constitution Staff Writer)

The state Board of Pardons and Paroles refused to save Fred Gilreath from his scheduled execution for killing his wife and father-in-law, despite pleas from the relatives of the victims of a domestic dispute spawned by anger over a pending divorce.

Gilreath, 63, is scheduled to die by lethal injection at 7 p.m. Wednesday for shooting Linda Gilreath and her father, Gerritt Van Leeuwen, in 1979 when the two returned to her Cobb County home to collect her clothes.

"If my mother could talk now, she would say she didn't want him to die," said Christopher Kellett, who was 8 when his father shot his mother. "We've lost enough. ... We don't want to lose any more."

Kellett reconciled with his father a year ago and has since introduced his children to their grandfather. Kellett said the board meeting was "very emotional."

Kellett, his sister and aunt -- sister to one victim and daughter of the other -- spent 90 minutes with the board, pleading that the members spare Fred Gilreath, who would be the third person to die by lethal injection in Georgia in less than three weeks.

Cobb County District Attorney Pat Head, who was not in office when Gilreath was prosecuted, met with four members of the board later in the day -- one individually and then three later in the afternoon -- to encourage them to deny the request for clemency. Board member Gene Walker was in Las Vegas, where he was attending a conference unrelated to board business.

Head said he told board members, "I believe this case was an appropriate case for the death penalty."

He said victims' wishes should not dictate the punishment. "We are a society of laws, and if we allow emotions to dictate decisions ... we put society at risk," Head said after his meetings with the board. "This was a brutal murder."

According to trial testimony, Linda Gilreath planned to file for a divorce from her husband of about 11 years. She had moved in with her mother even though her father continued to live in the house he shared with Linda and Fred Gilreath.

Fred Gilreath had been drinking when his wife came home on May 11, 1979, to retrieve some belongings. Ten minutes after they arrived,, Gilreath, using a shotgun and two rifles, shot Linda Gilreath five times and Leeuwen four times. He doused the bodies with gasoline and fled to another state, to the home of a relative who turned him in to police.

In the past, all five board members have been present for commutation hearings, but Walker said Tuesday the trip to Las Vegas had been planned for a long time. The vote is secret but at least three votes are needed to commute a sentence.

While not saying how he voted, Walker said he made his decision based on a review of Gilreath's file and board staff members' reports of the meetings Tuesday with Gilreath's supporters and the prosecutor.

"This is not a typical domestic dispute to me," Walker said. "This goes far beyond that. This is a man who murdered his wife and his wife's father. And he shot them multiple times and at different locations [in the house]. I have to assess all that. Clearly, I feel comfortable with where I am and what I'm doing."

Gilreath's only remaining hope lies with the courts, which already have rejected his pleas in previous appeals. A trial court in Butts County, the home of death row and the first step in death penalty challenges, turned down his appeal Monday.

"To kill Fred Gilreath will compound this tragedy," David Russell, Gilreath's attorney, said Tuesday. "It was an emotional reaction to his wife leaving him. The victims' relatives are also the relatives of Fred Gilreath. ... And the family of victims does not want this to happen."

______________________________________________

Atlanta Journal-Constitution (November 13, 2001)

"Family Asked That Condemned Killer be Spared," by Rhonda Cook.

The children and the sister-in-law of condemned killer Fred Gilreath pleaded with the state Board of Pardons and Paroles today to commute the Cobb County man's death sentence.

Gilreath is scheduled to die by lethal injection tomorrow evening for killing his wife and father-in-law during a 1979 domestic dispute that centered on Linda Gilreath's plans to divorce him.

Among those pleading for Fred Gilreath's life were Linda Gilreath's sister and Fred and Linda Gilreath's two children.

"If my mother could talk now, she would say she didn't want him to die," Christopher Kellett, Fred Gilreath's son said after meeting with the board for about 90 minutes. "We've lost enough... We don't want to lose any more."

Cobb County District Attorney Pat Head, who was not in office when Gilreath was prosecuted in 1980, has an appointment with the board this afternoon.

Only four of the five members were at the meeting with Gilreath's family and attorneys. Board member Gene Walker was out of town attending a conference.

It will take three votes to commute Gilreath's death sentence.

______________________________________________

Atlanta Journal-Constitution (Saturday, November 10, 2001)

"Death Sentence Decried," by Bill Rankin.

Fred Marion Gilreath's capital sentence should be overturned because so many similar murder cases have consistently ended with a sentence less than death, court motions filed Friday said.

Gilreath, convicted of the 1979 killings of his wife and father-in-law, committed "an unplanned, domestic murder that erupted in a heated dispute," the court motion said. And because death sentences are hardly ever imposed in domestic killings, Gilreath's capital sentence is "clearly disproportional" and therefore unconstitutional.

"It was a spur-of-the-moment, alcohol-fueled crime of passion by a person who had gone 42 years without a criminal conviction," Gilreath's lawyer, Brian Mendelsohn, said.

The Georgia Supreme Court, when reviewing each death penalty appeal, must determine whether the sentence was excessive or disproportionate to penalties imposed in similar cases.

On the day Gilreath's wife, Linda, filed for divorce and returned home with her father to get her clothes, Gilreath killed both of them.

This week, Gilreath's son, Chris Kellett of Newnan, said that he once believed his father deserved the death penalty. But now he wants his father's sentence commuted to life in prison. Kellett said his family, including his 3-year-old son Christian, regularly visits Gilreath on death row. On Tuesday, Kellett and his sister will ask the state Board of Pardons and Paroles to spare their father.

Tom Charron, the former Cobb County district attorney who prosecuted Gilreath, has described the case as an "exceptionally brutal double homicide" during which at least eight shots were fired. "This was not a classic domestic disturbance where the husband fires one shot and later regrets it," Charron said.

Still, Mendelsohn's court motion contends Gilreath "is in a class of one." Of the 25 people executed in Georgia since 1976, the motion noted, not one of them committed a crime arising from a domestic dispute.

______________________________________________

Atlanta Journal Constitution (Thursday, November 8, 2001)

"Son Hopes Execution Halted; Mother Slain, Now His Father Set to Pay Price," by Bill Rankin.

Chris Kellett was 8 years old when his father shot his mother five times and also killed his grandfather.

As he grew into manhood, Kellett may have had few certainties, but he had this one: He wanted his father dead. He supported the death penalty in general and believed his father had earned every last volt of it. A Cobb County jury agreed and, 22 years ago, sentenced Kellett's father to death.

"I felt it was a deserving sentence," the plainspoken Newnan man, now 31 and father himself, said Wednesday. "I believe in the death penalty --- did and still do."

But a year ago, for the first time since he was a teenager, Kellett visited his father, Fred Marion Gilreath, 62, on death row and everything changed.

Kellett no longer wants his father executed by the state. He said that next week, he and his sister will ask the state Board of Pardons and Paroles to commute Gilreath's death sentence to life in prison. Gilreath is scheduled to die by lethal injection next Wednesday, a little more than a month after the electric chair was declared unconstitutional.

On May 11, 1979, Gilreath killed his estranged wife, Linda, and her father when they came to the Gilreath house to get her clothes. On that day, Linda was filing for divorce to get away from her husband, described in court as an abusive alcoholic.

Tom Charron, who prosecuted the case as Cobb County district attorney, said Wednesday that he empathizes with the family but believes Gilreath deserves capital punishment. "It was an exceptionally brutal double homicide," he said. "He used three separate weapons to carry out the murders. The amount of viciousness involved was more than enough to warrant the death sentence he got."

As for the Board of Pardons and Paroles, he said, "You always want to listen. If anyone should have anything to say on this issue, it should be those children. They are the real victims for having to grow up without a mother for 22 years."

Kellett said that at the time of the shootings, he understood his mother and grandfather had been killed. Afterward, he said, he lived with relatives and then at a boys home before attending college.

While meeting with his father last Thanksgiving, Kellett said, Gilreath asked for forgiveness. "I've learned that it's a lot easier to hate someone than to forgive them," Kellett said in an interview at Gilreath's attorney's office. But he said he forgave his father.

Almost every other weekend for a year, Kellett said, he has taken his family to visit Gilreath on death row. He said his 3-year-old son, Christian, loves to see his grandfather. "We tell him we're going to see Poppy, and it's a treat," Kellett said.

Kellett admits that his support for the death penalty conflicts with his opposition to his father's execution. "I felt hypocritical at first, like I was contradicting myself," Kellett said. "I know that he took away plenty from us, but he's finally giving something back now. . . If you could see my son's reaction every time he sees his grandfather, I think it would soften anyone's views."

JACKSON, Georgia, Nov 15 - A man convicted of killing his wife and father-in-law during a 1979 domestic dispute was put to death in Georgia on Thursday, the third execution in the state in the past three weeks.

Fred Gilreath, 63, was injected with lethal chemicals in the death chamber at the state prison in Jackson, Georgia, after federal courts rejected pleas to stop the execution, Georgia Department of Corrections spokesman Scott Stallings said.

Stallings said Gilreath issued a final statement in which he thanked his attorneys, family and prison staff. "God bless everybody," were his final words. Gilreath died at 3:53 p.m.

Gilreath had originally been scheduled to die on Wednesday night, but the inmate won a temporary reprieve after the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed to review a lawsuit filed by his lawyers against the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles.

The lawsuit claimed that board members acted improperly on Tuesday during a clemency hearing when they voted to reject his request to have the death sentence commuted to life in prison.

The lawsuit noted that one of the five members of the board was not present for the hearing.

But on Thursday the 11 Circuit Court turned down arguments from Gilreath's lawyers that there was a legal basis for halting the execution. The U.S. Supreme Court also refused to intervene.

Gilreath was sentenced to death for shooting his wife Linda, 28, and her father Gerritt Van Leeuwen, 57, on May 11, 1979. Linda Gilreath had been planning to file for divorce to get away from her husband, later described in court as an abusive alcoholic.

Gilreath's wife was shot five times with a rifle and once in the face with a shotgun. Her father was shot several times with a rifle, shotgun and handgun. Police found gasoline on both bodies and in the kitchen of the Gilreath house.

Defense lawyers as well as Gilreath's children had urged state officials to show leniency on the grounds that the killings were a crime of passion fueled by alcohol and intense emotions.

Gilreath became the third inmate to be put to death in Georgia since the state Supreme Court ruled last month that the use of the electric chair to execute inmates was unconstitutional because it inflicted needless suffering.

Georgia switched to lethal injection after the ruling.

Alabama and Nebraska are the only states that still rely solely on electrocution to execute inmates. The other 35 states with the death penalty use lethal injection or give the inmate a choice in deciding the method of execution.

There are now 125 prisoners on Georgia's death row.