Executed September 19, 2013 8:41 p.m. CDT by Lethal Injection in Texas

25th murderer executed in U.S. in 2013

1345th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

12th murderer executed in Texas in 2013

504th murderer executed in Texas since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(25) |

Robert Gene Garza H / M / 20 - 31 |

Maria De La Luz Bazaldua Cobbarubias H / F / 31 Vasquez Beltran H / F / 21 Celina Linares Sanchez H / F / 22 Lourdes Yesenia Araujo Torres H / F / 20 |

Citations:

Garza v. State, Unpub. LEXIS 340 (Tex.Crim.App. April 30, 2008). (Direct Appeal)

Garza v. State, 213 S.W.3d 338 (Tex.Crim.App. 2007). (Direct Appeal)

Garza v. Thaler, 487 Fed. Appx. 907 (5th Cir. 2012). (Federal Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Texas no longer offers a special "last meal" to condemned inmates. Instead, the inmate is offered the same meal served to the rest of the unit.

Final/Last Words:

“I want to thank all of my family and friends for supporting me. I love you and I’m glad y’all are by my side through this whole thing. I know it’s hard for y’all. Thank God for you being there for me. It’s not easy, this is a release. Y’all finally get to move on with your lives.”

Internet Sources:

Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Executed Offenders

Garza, Robert

Date of Birth: 05/15/1982

DR#: 999466

Date Received: 12/18/2003

Education: 8 years

Occupation: Laborer

Date of Offense: 09/05/2002

County of Offense: Harris

Native County: Hidalgo

Race: Hispanic

Gender: Male

Hair Color: Black

Eye Color: Brown

Height: 5' 07"

Weight: 147

Prior Prison Record: #1090018 on a 2 year sentence from Hidalgo County for escape.

Summary of Incident: On 09/05/2003, in Hidalgo County, Texas, Garza and co-defendants killed four Hispanic females by firing into the victims' car. It was later discovered that Garza and his co-defendants were members of the Tri City Bomber Gang, carrying out orders to murder one of the females who was a witness to their weapons activity.

Co-Defendants: M. Reyna, G. Guerra, R. Medrano, A. Medrano, J. Cordova, J. Juarez, M. Bocanegra, S. Solis, J. Martinez, J. Ramirez, H. Garza, R. Saucedo, R. Cantu

Race and Gender of Victim: Hispanic/Females

Tuesday, September 17, 2013

Media Advisory: Robert Gene Garza scheduled for execution

AUSTIN – Pursuant to an order entered by the 398th District Court in Hildago County, Robert Gene Garza is scheduled for execution after 6 p.m. on September 19, 2012. In 2003, a Hildago County jury found Garza guilty of murdering Maria De La Luz Bazaldua Cobbarubias, Dantizene Lizeth Vasquez Beltran, Celina Linares Sanchez, and Lourdes Yesenia Araujo Torres.

FACTS OF THE CRIME

The United States Court of Appeals for the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas described the murder as follows:

At around midnight on September 4, 2002, Maria De La Luz Bazaldua Cobbarubias headed home from her job as a barmaid at Garcia’s Bar in Donna, Texas. She offered to give five coworkers – Dantizene Lizeth Vasquez Beltran, Celina Linares Sanchez, Lourdes Yesenia Araujo Torres, Karla Espino Ramos and Magda Torres Vasquez – a ride to the mobile home where they all lived. Another woman – Nora Rodriguez – remained behind to close the bar. Ms Cobbarubias did not notice a vehicle following them to their home on Valley View Road. After she parked the car near their trailer, gunfire erupted.

Eyewitnesses saw the vicious assault on Ms. Cobbarubbias’ car, though no one could conclusively identify the shooters. Witnesses saw two men wearing black repeatedly fire into the vehicle. The police later recovered sixty-one spent shell cases from the scene. All but one of the women suffered gunshot wounds. Four of them – Cobbarubias, Beltran, Sanchez, and Torres – died. After riddling the victims’ car with bullets, the men got into the vehicle that had followed the women and sped away. The gunmen abandoned their vehicle a few miles away after it had run out of gas.

Police investigation uncovered many false leads and unsubstantiated rumors about the four murders. Their attention soon turned to members of a local criminal gang involved in murder, robbery, drug running, assault, and theft. Information led the police to believe that a leader of the [local criminal gang] who was serving time for attempted murder had ordered a hit on Ms. Rodriguez because she had witnessed a shooting in Garcia’s Bar and later testified against him. In carrying out that hit, the gunmen who intended to kill Ms. Rodriguez slaughtered the victims by mistake.

Informants pointed to Garza as a possible gunman. Garza was a member of the [local criminal gang] with tattoos attesting to his gang affiliation. The police believed that Garza had also been involved in the January 4, 2003, gang-related killing of six people in nearby Edinburg, Texas. In that crime – known colloquially as the Edinburg massacre – the [local criminal gang] orchestrated a fake police assault on two houses in a failed attempt to steal drugs.

On January 24, 2003, the police arrested Garza and questioned him about his involvement in the Edinburg massacre. He confessed. Two days later, an officer from the Hidalgo County Sheriff’s Office interviewed him about his role in the Donna killings. Garza wrote a statement confessing that he helped prepare for the murders and followed the gunmen to the trailer house, but he did not admit to being one of the shooters. Garza wrote that he and another man “received instruction[s] to carry out a hit that resulted in the death of four [women]. The hit was organized for us.” After getting vehicles and a gun, Garza followed another car to the crime scene, saw two fellow gang members get out, and “then shots rang out.” The two cars drove away, until the car Garza was in broke down. The gang leader who ordered the hit “was mad ‘cause it wasn’t done right.”

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

In September 2002, a Hildago County grand jury indicted Garza for murdering Maria De La Luz Bazaldua Cobbarubias, Dantizene Lizeth Vasquez Beltran, Celina Linares Sanchez, and Lourdes Yesenia Araujo Torres.

A Hildago County jury found Garza guilty of capital murder. After the jury recommended capital punishment, the court sentenced Garza to death. Judgment was entered Dec. 17, 2003.

On April 31, 2007, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals rejected Garza’s direct appeal and affirmed his conviction and sentence. Garza did not appeal to the United States Supreme Court.

Garza also sought to appeal his conviction and sentence by filing an application for a state writ of habeas corpus with the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. On Sept. 10, 2008, the high court denied Garza’s application for state habeas relief.

On Oct. 2, 2009, Garza attempted to appeal his conviction and sentence in the federal district court for the Southern District of Texas. The federal district court denied his petition for federal writ of habeas corpus on Sept. 15, 2011.

On Aug. 27, 2012, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit denied Garza’s request for certificate of appealabilty on his federal writ of habeas corpus.

On Feb. 19, 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Garza’s appeal when it denied his petition for a writ of certiorari off federal habeas.

PRIOR CRIMINAL HISTORY

Under Texas law, the rules of evidence prevent certain prior criminal acts from being presented to a jury during the guilt-innocence phase of the trial. However, once a defendant is found guilty, jurors are presented with information about the defendant’s prior criminal conduct during the second phase of the trial – which is when they determine the defendant’s punishment.

During the penalty phase of Garza’s trial the jury heard that was ordered to the Hidalgo County Youth Village, a residential facility for boys in February 1997. And later that year, Garza was ordered into the custody of the Texas Youth Commission (TYC) for burglary of a habitation. In February 2002, Garza was sent to the Texas Department of Correction (TDC) for escape. Several employees with the Hidalgo County Sheriff’s Department testified to Garza’s attempted escape from county jail in April 2003.

Texas Execution Information Center by David Carson.

Robert Gene Garza, 30, was executed by lethal injection on 19 September 2013 in Huntsville, Texas for the gang-related murder of four women.

On the evening of 4 September 2002, six women were working at Garcia's Bar in Donna, a town in the Rio Grande valley, east of McAllen. After the bar closed at midnight, they rode together in a Pontiac Grand Am to their trailer home outside of town. After the car stopped, but before anyone could exit, dozens of gunshots were fired into the car. Four of the women - Maria Cobarrubias, Danitzene Beltran, Celina Sanchez, and Lourdes Torres - died. Karla Ramos survived gunshot wounds to her arm and leg. Magda Vasquez was uninjured.

Donna police officer Alejandro Martinez was the first officer to arrive at the scene. Witnesses told him that a Chevrolet Blazer had been parked close to the trailer at the time of the shooting. The vehicle was white, had paper license tags, and no hubcaps. Martinez, finding that the crime occurred outside Donna city limits, contacted the Hidalgo County sheriff's office. Investigators with that office recovered 61 bullet casings from the scene. The rounds were 9mm and 7.76mm. Investigators also found an abandoned, out-of-gas Chevrolet Blazer matching the description given to Officer Martinez a few miles from the trailer park. It had been reported stolen a few days earlier. It contained some items of clothing that did not belong to the vehicle's owner, including a red bandana with white markings.

Based on statements taken from the surviving victims, authorities investigated three men who had been in Garcia's Bar on the night of the shooting, but they were unable to find any evidence connecting any of them to the crime. They also investigated several other bar patrons and pursued some anonymous tips, but after a few weeks, they were left with no suspects.

On 5 January 2003, four months after the murders, six people were found shot to death in two houses on a semi-rural cul-de-sac in Edinburg, also in Hidalgo County. The incident, known locally as the "Edinburg Massacre," immediately drew comparisons with the Donna slayings from the public and the media. Police investigated the TriCity Bombers gang, or T.C.B., for the killings. Through their investigation, several members of the gang, including Garza, then 19, became suspects in the Donna slayings. Prosecutors advanced the theory that the Donna killings were ordered by T.C.B. leader Jesus Carlos Rodriguez, who was awaiting trial for an attempted murder committed at Garcia's Bar on 31 March 2001. Two women, Nora Rodriguez and Mercedes Quintero, had witnessed the incident and had been called to testify. Both women lived at the trailer park where the murders were committed. Nora Rodriguez was also the manager of Garcia's Bar. Prosecutors said that the hitmen made a mistake and killed the wrong targets.

On 26 January, Garza was taken to the Hidalgo County sheriff's office, where he gave a confession. Garza stated that he had been instructed concerning an arranged hit, and on 5 September, he received instructions that the hit was to be carried out that day. At approximately 7 p.m., Ricardo Martinez picked up Garza and Mark Anthony Reyna in a four-dour sedan, either a Buick Cutlass or Regal. They then picked up a fourth person, later identified as Guadalupe Guerra, but who Garza simply called "Manny." An AK-47 assault rifle, a TEC-9 handgun, and another 9mm handgun were in the trunk of the vehicle. According to Garza's confession, the men drove by Garcia's Bar, then went to pick up a second vehicle, which had been stolen. Garza and Reyna got in the second vehicle and waited for "them" to come. They later saw two vehicles drive by - a Grand Am and the Buick - and followed them. When the vehicles stopped, Martinez and Guerra got out of the Buick and started shooting. They then left the scene and abandoned the Buick. They drove around in the second vehicle until it "broke down," then they left on foot. Garza added that "Rocha" - J.C. Rodriguez - "was mad 'cause it wasn't done right."

Investigators recovered a TEC-9 from a gang member's grandparents' house and determined that it fired 18 of the 9mm casings recovered from the scene. Three 7.76mm Chinese-made SKS military rifles were found at a gang member's friend's house. Firearms specialist Tim Counce testified that he could not "identify or eliminate" any of the SKS rifles as murder weapons. He further testified that the SKS rifles could appear to be AK-47s to the untrained eye. Detective Roberto Alvarez testified that the TriCity Bombers identified themselves by the colors red and black and often carried and wore red shirts and bandannas. Robert Garza had a tattoo on his chest with the words "Tri City Bomber" and the initials "T.C.B.", along with various other tattoos on other body parts, signifying his membership in the gang.

In pre-trial proceedings, Garza's lawyers attempted to prevent his confession from being admitted into evidence. In an amended statement, Garza wrote that he did not commit the crime, and only "wrote what the investigators told me, to get things I wanted." Garza stated that he was told that if he confessed, he would be allowed to make some phone calls, would be allowed to see his pregnant wife, and would be released from "the hole" to the general jail population. In response, investigator Juan Sifuentes testified that he offered no favors or promises to Garza for his confession. Garza did get to make some phone calls and see his wife, Sifuentes said, but that was independent of his statement. Sifuentes said he had nothing to do with where prisoners were kept in the jail. The judge ruled against Garza and allowed his confession to be admitted. Two trailer park residents who witnessed the shooting testified that it was committed by two men wearing black clothing.

Under Texas law, a defendant can be found guilty of capital murder for being a party to a killing if he intended to kill the victim or "anticipated that a human life would be taken," even if he did not directly cause the victim's death.

A jury found Garza guilty of capital murder in December 2003 and sentenced him to death. He was also convicted of committing capital murder while engaging in organized criminal activity and given a second death sentence. He was also given a life sentence for the attempted capital murder of the surviving victims. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed Garza's first capital murder conviction and death sentence in January 2007. The second capital murder conviction was also affirmed, but the appeals court vacated that death sentence, and he was subsequently given a life sentence. All of Garza's subsequent appeals in state and federal court were denied.

Texas Department of Criminal Justice records name Garza as a co-defendant in the Edinburg killings, but he was not brought to trial for them. Three men - Humberto Garza, Rodolfo Medrano, and Juan Ramirez - received death sentences in that case, and are currently on Texas' death row in Livingston. No information on the three men Garza named as accomplices in the Donna murders - Mark Anthony Reyna, Guadalupe Guerra, and Ricardo Martinez - was available for this report.

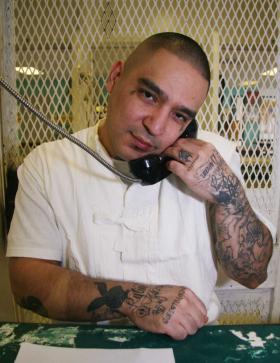

In an interview from death row in July 2013, Garza denied involvement in either of the multiple murders. "I wasn't there. I didn't kill nobody," he said. He did, however, acknowledge that he was aware of a planned hit by his gang. "I had knowledge of it, you know, prior to it, so probably I'm at fault for not preventing it." "I lived the life of a thug," Garza said. "I was in the streets. I was a gang member, you know."

Garza said he regretted the suffering he had caused. "Definitely, I feel remorse for the family, for the victim, for the victim's children, for my family, I mean for everybody," he said. "Not just for that case, but for my whole past, the people I've hurt in my past." Garza said he has grown and changed during his ten years on death row. "I think I'm a totally different person today than I was back then," he said. While in prison, Garza received two additional 8-year sentences for aggravated assault on a public servant.

Garza's execution was delayed for about two hours as the U.S. Supreme Court considered his final appeal, which he filed on his own. Gaza expressed love to his family in his brief last statement. He did not address or acknowledge the victims' families. The lethal injection was started, and he was pronounced dead at 8:41 p.m.

Some death-penalty watchers had been speculating that Garza's execution would be the last one performed in Texas using the chemical pentobarbital. Companies that manufacture the sedative - long used for animal euthanasia and legal human euthanasia - object to its use in executions, and have banned its sale to state prisons. Other states have had to switch to other drugs for their lethal injections, but Texas had enough of a supply on stock to last to September. That stock, however, expires this month. A spokesman for the Texas prison system said yesterday that the state will continue to use pentobarbital. He did not disclose how the prison will obtain its supply. Texas has another execution scheduled for September, and four more through the end of the year. When U.S. states began performing executions via lethal injection in the 1980s, they used a series of three drugs, the first of which was sodium thiopental. In 2011, the only lab manufacturing sodium thiopental stopped exporting it to the U.S., so the death-peanlty states have switched to pentobarbital.

"Texas man executed for ambush that killed 4 women." (ASSOCIATED PRESS September 20, 2013)

HUNTSVILLE - A former South Texas street gangster was executed Thursday evening for his involvement in an ambush in which four women were gunned down 11 years ago. Robert Gene Garza, 30, was the 12th inmate executed this year in Texas.

Garza smiled and blew a kiss to friends and relatives as they entered the death chamber. In a brief final statement, he thanked them for coming and said he loved them. "I know it's hard for you," he said. "It's not easy. This is a release. Y'all finally get to move on with your lives." He was pronounced dead at 8:41 p.m., 26 minutes after a dose of pentobarbital began flowing into his arms.

A longtime member of a Rio Grande Valley gang known as the Tri-City Bombers, Garza insisted a statement admitting his participation in the September 2002 shootings in Hidalgo County was made under duress and improperly obtained. But prosecutors said Garza orchestrated the plan to silence the women, who he thought had witnessed another gang crime. "I really didn't have anything to do with the scenario the state was providing," Garza told The Associated Press recently from death row. "I think they were just trying to close his case … and they needed somebody." Evidence later showed the women were killed by mistake.

Garza was arrested in late January 2003 and convicted under Texas' law of parties, which makes a non-triggerman equally culpable. Evidence showed Garza was a gang leader, told his companions how to do the killings and was present when the shootings took place, Hidalgo County prosecutor Joseph Orendain said this week.

"TDCJ Execution: Gang member executed for murders of 4," by Cody Stark. (September 19, 2013)

HUNTSVILLE — A South Texas gang member was put to death Thursday for his role in the 2002 mass killing of four women who were ambushed while sitting in a parked car outside their home in Hidalgo County. Robert Gene Garza, 30, was pronounced dead at 8:41 p.m., 26 minutes after the lethal dose was administered. The execution was delayed two hours before the United States Supreme Court denied Garza’s last-day appeals. He became the 12th death row inmate to be put to death in Texas this year.

Maria De La Luz Bazaldua Cobbarubias, Dantizene Lizeth Vasquez Beltran, Celina Linares Sanchez and Lourdes Yesenia Araujo Torres were gunned down in the ambush, which happened near the South Texas town of Donna. Two other women survived. Garza did not acknowledge the family of some of the victims who were present Thursday. He did thank his family for all the support they have shown him during the 10 years he was on death row. “I want to thank all of my family and friends for supporting me. I love you and I’m glad y’all are by my side through this whole thing,” he said. “I know it’s hard for y’all. ... Thank God for you being there for me. It’s not easy, this is a release. Y’all finally get to move on with your lives.”

Garza’s execution could be the last using the state’s existing supply of pentobarbital, the drug used to carry out executions. Texas Department of Criminal Justice officials said in August that its supply of the drug will run out this month and the agency is looking for a substitute. Manufacturers of pentobarbital have refused to sell the state the drug because it is used for executions. There is an execution scheduled for next week, three in October and one both November and December.

Garza filed his own appeals Thursday to the Supreme Court, arguing his trial attorneys failed to obtain from his mother testimony jurors should have been allowed to hear that he stayed in the gang because he feared retaliation if he quit. He also contended his trial court judge earlier this week improperly refused his request to withdraw his execution date. Garza argued the state should assure him the lethal dose of pentobarbital to be used in his punishment was chemically effective and obtained legally.

A member of a Rio Grande Valley gang known as the Tri-City Bombers even before he was a teenager, Garza insisted a statement to police acknowledging his participation in the September 2002 shootings in Hidalgo County was made under duress and improperly obtained. But prosecutors said Garza orchestrated the gang’s plan to silence the women, who he thought had witnessed another gang crime, and was present when several gang members opened fire on the women when they arrived at their trailer park home after work at a bar. Evidence later would show the women were killed by mistake. The gang member in that case never went to trial because he accepted a plea deal and prison term.

Garza, who was arrested in late January 2003, was convicted under Texas’ law of parties, which makes a non-triggerman equally culpable. Evidence showed Garza was a gang leader, told his companions how to do the killings, was present when the shootings took place and “in all likelihood was a shooter but is downplaying his part,” Joseph Orendain, the Hidalgo County assistant district attorney who prosecuted him, told the Associated Press this week.

Garza also was charged but never tried for participating in what became known in the Rio Grande Valley as the Edinburg massacre, the January 2003 slayings of six people at a home in the city.

"Ex-South Texas gang member executed for deaths of 4 women in 2002." (Updated: 19 September 2013 09:32 PM)

HUNTSVILLE — A former South Texas street gang member was executed Thursday evening for his involvement in a gang ambush where four women were gunned down 11 years ago. Robert Gene Garza, 30, became the 12th condemned inmate executed this year in Texas, which carries out capital punishment more than any other state. Garza smiled and blew a kiss to friends and relatives as they entered the death chamber. In a brief final statement, he thanked them for coming and told them he loved them. “I know it’s hard for you,” he said. “It’s not easy. This is a release. Y’all finally get to move on with your lives.” He was pronounced dead at 8:41 p.m. CDT, 26 minutes after a lethal dose of pentobarbital began flowing into his arms.

A member of a Rio Grande Valley gang known as the Tri-City Bombers even before he was a teenager, Garza insisted a statement to police acknowledging his participation in the September 2002 shootings in Hidalgo County was made under duress and improperly obtained. But prosecutors said Garza orchestrated the gang’s plan to silence the women, who Garza thought had witnessed another gang crime, and was present when several gang members opened fire on the women when they arrived at their trailer park home after work at a bar. “I really didn’t have anything to do with the scenario the state was providing,” Garza told The Associated Press recently from death row. “I guess since we are gang members, they got me involved through the gang. “I think they were just trying to close his case … and they needed somebody.” Evidence later would show the women were killed by mistake. The gang member in the other crime never went to trial because he accepted a plea deal and prison term.

Garza, who was arrested in late January 2003, was convicted under Texas’ law of parties, which makes a non-triggerman equally culpable. Evidence showed Garza was a gang leader, told his companions how to do the killings, was present when the shootings took place and “in all likelihood was a shooter but is downplaying his part,” Joseph Orendain, the Hidalgo County assistant district attorney who prosecuted him, said this week.

In February, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review his case. His lawyer, Don Vernay, said appeals were exhausted. Garza filed his own last-day appeals Thursday to the high court, arguing his trial attorneys failed to obtain from his mother testimony jurors should have been allowed to hear that he stayed in the gang because he feared retaliation if he quit. He also contended his trial court judge earlier this week improperly refused his request to withdraw his execution date. Garza argued the state should assure him the lethal dose of pentobarbital to be used in his punishment was chemically effective and obtained legally. Texas prison officials have said their inventory of pentobarbital is expiring this month.

Texas prison officials said Thursday that they will continue to use the same drug but wouldn’t say how the state will replace its supply. “We have not changed our current execution protocol and have no immediate plans to do so,” Texas Department of Criminal Justice spokesman Jason Clark said in a statement to The Associated Press.

Garza also was charged but never tried for participating in what became known in the Rio Grande Valley as the Edinburg massacre, the January 2003 slayings of six people at a home in the city. In the case that sent him to death row, Garza was convicted of two counts of capital murder for the slayings of the four women. Evidence showed they were living in the U.S. without legal permission just outside Donna, about 15 miles southeast of McAllen. In his statement to investigators, which Garza insisted was coerced, he said he carried out the “hit” with three other gunmen in two vehicles who opened fire on six women in their parked car. Killed were Maria De La Luz Bazaldua Cobbarubias, Dantizene Lizeth Vasquez Beltran, Celina Linares Sanchez and Lourdes Yesenia Araujo Torres. Two others survived. Another Texas inmate is set to die next week.

Victims: Maria Cobarrubias, Danitzene Beltran, Celina Sanchez, Lourdes Torres , Jimmy Almendariz, 22, Jerry Hidalgo, 24, Ray Hidalgo, 30, Juan Delgado Jr., 32, Juan Delgado III, 20, Ruben Castillo, 32

On the evening of September 4, 2002, Maria De La Luz Bazaldua Cobarrubias, Danitzene Lizeth Vasquez Beltran, Celina Linares Sanchez, Lourdes Yesenia Araujo Torres, Karla Espino Ramos, and Magda Torres Vasquez were working at Garcia's Bar in Donna, Texas. When the bar closed at midnight, Cobbarubias gave the other women a ride to their trailer home. She drove south on Business 83, turned onto Valley View Road, and then parked close to the women's trailer. Before anyone had a chance to get out of the vehicle, shots were fired. Cobbarubias, Beltran, Sanchez, and Torres sustained multiple gunshot wounds and died from their injuries. Ramos sustained gunshot wounds to her arm and leg, but survived. Vasquez did not sustain any physical injuries.

Alejandro Martinez of the Donna Police Department was the first officer to arrive at the scene. He determined that the shooting had actually occurred just outside the Donna city limits and contacted the Hidalgo County Sheriff's Office. Several witnesses told Martinez that a Chevrolet Blazer had been parked close to the trailer at the time of the shooting. The vehicle was white, had paper plates, and did not have any hubcaps. Investigators with the Hidalgo County Sheriff's Office recovered sixty-one spent bullet casings from the trailer park, which were of two different sizes: 9 millimeter and 7.76 x 39 millimeter. Most of the casings were recovered from a driveway located directly behind where the victim's Pontiac Grand Am was parked. Investigators also impounded a Chevrolet Blazer a few miles from the trailer park. The vehicle was white, had paper plates, and did not have any hubcaps. It had been reported stolen a few days earlier. Several items of clothing that did not belong to the vehicle's owner were recovered from the vehicle, including a red bandana with white markings. The vehicle had run out of gas.

Juan Antonio Quintero, a neighbor, testified that he saw two people at the time of the shooting. One of them was short and "chubby" and the other one was tall and "skinny." Both of them were wearing black. He noticed that the short person was holding a gun that "looked like a TEC-9." He testified that he could not see their faces, but thought one of them "resembled" Vasquez's boyfriend, Jesse Munoz. Carlos Villarreal, J.A. Quintero's guest, told investigators that he saw two people at the time of the shooting. One of them appeared to be between 5'10'' and 5'11'' and 160 pounds. The other person was 5'8'' and 250 pounds. At trial, prosecutors introduced Robert Garza's booking sheet which showed that he was 5'11'' and 160 pounds.

Investigator Juan Sifuentes testified that, because of information they had received, patrons at Garcia's Bar were suspected in the shooting. Ramos told investigators that Abraham Martinez Tienda, who had been in Garcia's Bar on the evening of the shooting, shot the women. Vasquez told investigators that she suspected her boyfriend, Juan Rudolfo Barrones, who had been in Garcia's Bar on the evening of the shooting. Another suspect was Antonio Francisco Conteras, because he had followed the victim's car to the trailer park on the evening of the shooting. Sifuentes testified that they investigated Tienda, Barrones, and Conteras, but could not find any evidence linking them to the shooting. They also investigated several other bar patrons and pursued tips they received from the Crime Stoppers program. However, this investigation did not lead anywhere, and after a few weeks they were left with no suspects.

In January 2003, Abraham Osequera and Marco Antonio Mendez told investigators that they believed that members from their criminal street gang, the TriCity Bombers, the "T.C.B.," could be involved. They gave investigators information pointing towards T.C.B. members Jesus Carlos Rodriguez and Mark Anthony Reyna. Also, investigators received information from J.A. Quintero and his aunt, Mercedes Quintero, implicating the T.C.B. Through further investigation, other T.C.B. members emerged as possible suspects including Garza, Rudolfo Medrano, Guadalupe Guerra, and Ricardo Martinez. The State's theory of the case was that J.C. Rodriguez, who was serving time for attempted murder, ordered "a hit" on Nora Rodriguez and M. Quintero because they had been called to testify against him, but that the wrong women were killed by mistake.

N. Rodriguez testified that she and M. Quintero witnessed J.C. Rodriguez commit the attempted murder on March 31, 2001, and were called to testify about the incident. To support this theory, the State introduced a judgment showing that J.C. Rodriguez was sentenced to twenty years' imprisonment for an attempted murder committed on March 31, 2001. On January 26, 2003, Garza was taken to the Hidalgo County Sheriff's Office. After receiving Miranda warnings and signing a waiver, Garza gave a statement describing his own involvement in "a hit" which "resulted in the death of four Donna womans." Garza explained that the "hit was organized for us" and that someone left a four-door "Cutlass or Regal" at Plaza Mall to be used in "the hit." Garza was "hoping it would be left alone," but on September 5, 2002, he received instructions "that the hit was to be carried out that day." At approximately 7:00 p.m., Martinez picked up Garza and Reyna in a four-door vehicle. Garza saw that Martinez had an AK-47, a TEC-9, and a nine-millimeter handgun in the trunk of the vehicle. They picked up a fourth person, "Manny," and drove "around Donna to see the bar which was located on old [highway] 83." Then they left Donna to pick up a "second vehicle," which had been stolen. Garza and Reyna got into the second vehicle and waited in the "middle of nowhere" until they saw "them" coming. They saw two vehicles pass by, a "Grand Am" and Manny's and Martinez's vehicle, and followed them to "a big house" or an "apartment complex." Martinez and Manny got out of their vehicle and started shooting. Garza saw that Manny "shot as he ran" and Martinez shot "as he stood." After the shooting, they left the scene and abandoned the four-door vehicle "in the middle of nowhere." Then they left the weapons in the trash where they could pick them up the next day. They drove around in the second vehicle for a while until it "broke down," and they left on foot. Finally, Garza stated that: "Apparently Rocha was mad 'cause it wasn't done right."

Medrano, who kept weapons for the T.C.B., told investigators that he knew where the weapons used in the Donna shooting were located. He directed investigators to a black box he kept in his grandparents' house. Also, he directed investigators to the residence of fellow T.C.B. member Robert Zamora, Jr. Zamora subsequently took investigators to his friend Nicholas Montez's residence. Firearms specialist Timothy Counce testified that a TEC-9 gun, which had been seized at Medrano's grandparents' house, fired eighteen of the nine-millimeter cartridge casings found at the scene. Further, Counce testified that he had been unable to "identify or eliminate" three Chinese-manufactured SKS military assault rifles, which had been seized at Montez's residence, as having fired the 7.76 x 39 millimeter cartridge casings found at the trailer park. The SKS rifles could appear to be AK-47 rifles to the untrained eye. Detective Roberto Alvarez testified that the T.C.B. was a highly organized criminal street gang that was connected with various crimes including murder, robbery, assault, burglary, and theft. Members identified themselves by the colors red and black; they often carried red bandannas, drove red cars, and wore red t-shirts. They commonly used a hand symbol and tattoos to show their affiliation with the gang. Alvarez testified that photographs depicting Garza wearing red shirts and making the T.C.B. hand symbol confirmed his affiliation with the T.C.B., as did photographs of his tattoos. The tattoo photographs showed the words "Tri City Bomber" and the initials "T.C.B." on his chest, the words "tri" and "city" and a bomb with a fuse on his right shoulder blade, the initials "T.C.B." on his right leg, the nickname "bones" and a skull on his right arm, and a small bomb on his left arm. Over counsel's objection, Garza was required to take off his shirt and display his tattoos to the jury.

Garza v. State, Unpub. LEXIS 340 (Tex.Crim.App. April 30, 2008). (Direct Appeal)

Appellant was indicted for two counts of capital murder. 2 In March 2005, the jury convicted appellant of the lesser-included offense of murder in Count One and assessed a life sentence. 3 The jury also convicted appellant of capital murder in Count Two. 4 Based on the jury's answers to the special issues set forth in Texas Code of Criminal Procedure Article 37.071, sections 2(b) and 2(e), the trial judge sentenced appellant to death for Count Two. 5 The direct appeal of Count Two to this Court is automatic. 6 After reviewing appellant's thirty-three points of error, we affirm the trial court's judgment and sentence of death in Count Two.

I.STATEMENT OF FACTS

This trial involved the gang-related, "pseudo-cop" robbery-homicide of six men, some of whom were members of the "Texas Chicano Brotherhood," a rival gang of the "Bombitas" or "Tri-City Bombers" gang to which appellant belonged. In the early morning hours of January 5, 2003, police responded to a 911 call and found the bodies of six men at 2915 East Monte Cristo Road in Edinburg. There were two houses on the property that were separated by a dirt driveway. Police found the body of Jerry Hidalgo in the kitchen of the larger house that was located on the west side of the driveway (the "west-side house"). 7 He was lying face down on the floor and his hands and legs were bound with extension cords. He had sustained numerous gunshot wounds, and there was a bullet hole in his back and blood around his head. The living room had been ransacked, and it appeared that someone had rummaged through one of the bedrooms, leaving the mattress standing on its side.

7 The "west-side house" had a kitchen, living room, two bedrooms, and a utility room. There was a storage shed behind it. An outhouse was located behind the "east-side house."

The body of Juan Delgado, III, was lying face down in the grass outside the front door of the smaller house on the east side of the driveway (the "east-side house"). He had suffered a fatal gunshot wound to the back of his neck. As they entered the house, police discovered the bodies of Juan Delgado, Jr., who had been shot in the back and head, and Jimmy Almendarez, who had suffered multiple gunshot wounds, including a fatal head wound. The bodies of Ray Hidalgo and Ruben Castillo were in another room. Ray had sustained two gunshot wounds to the head and was missing an eye. Ruben had suffered multiple gunshot wounds including shots to the buttocks. The "east-side house" had also been ransacked, and the victims' pockets had been pulled out. Police received information about a "pseudo-cop" robbery and took various suspects into custody, including appellant. Following his arrest, appellant gave a statement in which he admitted that he was a "captain" of the Tri-City Bombers, and that he and several other gang members put together a plan to steal what they believed was a significant amount of marihuana from the rival gang. He described his planning of the robbery and its ultimate execution, but denied being one of the actual killers. He stated that he and another gang member had "dropped off" the robbers at the murder scene and then picked them up afterwards.

II. In his first point of error, appellant contends that the trial court violated the federal and state constitutional protections against double jeopardy by subjecting him to multiple prosecutions and multiple punishments for the same offense. 8 Appellant admits that he did not make a double-jeopardy objection at trial. However, because of the "fundamental nature of the double-jeopardy protections," a double-jeopardy claim may be raised for the first time on appeal (1) when the undisputed facts show the double-jeopardy violation is clearly apparent on the face of the record and (2) when enforcement of the usual rules of procedural default serves no legitimate state interest. 9

8 U. S. Const. amend. V; Tex. Const. art. I, § 14. Appellant also claims that "[c]ollateral estoppel bars the conviction and sentence in the second prosecution styled 'Count Two.'" This claim is multifarious. Tex. R. App. P. 38.1(h). It is also without merit. As discussed herein, appellant was convicted and sentenced on both counts in a single proceeding. There was no "second prosecution." 9 Gonzalez v. State, 8 S.W.3d 640, 642-643 (Tex. Crim. App. 2000).

Count One of the indictment alleged that appellant . . . did then and there intentionally and knowingly cause the deaths of Jimmy Almendariz, Juan Delgado, III, Jerry Eugene Hidalgo, Juan Delgado, Jr., Ruben Castillo, and Ray Hidalgo, by shooting them with a firearm, and said murders were committed during the same criminal transaction[.] Count Two of the indictment alleged that appellant: . . . did then and there intentionally and knowingly cause the deaths of Jimmy Almendariz, Juan Delgado, III, Jerry Eugene Hidalgo, Juan Delgado, Jr., Ruben Castillo, and Ray Hidalgo, by shooting them with a firearm, and the defendant was then and there in the course of committing or attempting to commit the offense of robbery of Jimmy Almendariz, Juan Delgado, III, Jerry Eugene Hidalgo, Juan Delgado, Jr., Ruben Castillo, and Ray Hidalgo, and the defendant did then and there commit said capital murder as a member of a criminal street gang[.]

There were two jury charges, one for each count of capital murder. The charge in Count One defined capital murder as the murder of "more than one person during the same criminal transaction," and it authorized the jury to convict appellant as a party. 10 The charge in Count Two defined capital murder as murder "in the course of committing or attempting to commit the offense of Robbery," and authorized the jury to convict appellant as a party or a conspirator. 11 Both charges contained the same instruction on the lesser-included offense of murder:

10 Tex. Penal Code § 7.02(a). 11 Tex. Penal Code §§ 7.02(a) and 7.02(b).

Now, if you believe from the evidence beyond a reasonable doubt that on or about JANUARY 5, 2003 in Hidalgo County, Texas, ROBERT GENE GARZA a/k/a "BONES", RODOLFO MEDRANO a/k/a/ "CREEPER", MARCIAL BOCANEGRA a/k/a "MARSHALL", JUAN RAMIREZ a/k/a "RAM" a/k/a "LENNY", JUAN CORDOVA a/k/a "JUANON", SALVADOR SOLIS, a/k/a "LITTLE SAL", RICARDO MARTINEZ a/k/a "RICA" or "RICK", JUAN MIGUEL NUNEZ a/k/a "PERRO", REYMUNDO SAUCEDA a/k/a "KITO", JORGE ESPINOZA MARTINEZ, a/k/a "CHOCHE", or ROBERT CANTU a/k/a "ROBBIE," hereinafter known as CO-DEFENDANTS, did then and there did commit [sic] the felony offense of aggravated robbery of Jimmy Almendariz, Juan Delgado, III, Jerry Eugene Hidalgo, Juan Delgado, Jr., Ruben Castillo, or Ray Hidalgo, and that while in the commission of said aggravated robbery, if any, or while in immediate flight from the commission of such aggravated robbery, if any, one or more of the said CO-DEFENDANTS, did intentionally or knowingly or recklessly shoot any one of the following persons: Jimmy Almendariz, Juan Delgado, III, Jerry Eugene Hidalgo, Juan Delgado, Jr., Ruben Castillo, or Ray Hidalgo, and said act or acts were, under the circumstances then and there existing, were clearly dangerous to human life and that said acts or acts [sic] caused the death of any one of the following persons: Jimmy Almendariz, Juan Delgado, III, Jerry Eugene Hidalgo, Juan Delgado, Jr., Ruben Castillo, or Ray Hidalgo, and the Defendant, HUMBERTO GARZA, then and there knew of the intent, if any, of one or more of the said CO-DEFENDANTS, to rob Jimmy Almendariz, Juan Delgado, III, Jerry Eugene Hidalgo, Juan Delgado, Jr., Ruben Castillo, and Ray Hidalgo, by shooting any one of the following persons: Jimmy Almendariz, Juan Delgado, III, Jerry Eugene Hidalgo, Juan Delgado, Jr., Ruben Castillo, or Ray Hidalgo with a firearm, and the Defendant acted with intent to promote or assist the commission of the offense of aggravated robbery by one or more of the CO-DEFENDANTS, by encouraging, directing, aiding or attempting to aid one or more of the CO-DEFENDANTS, to commit the offense of aggravated robbery of Jimmy Almendariz, Juan Delgado, III, Jerry Eugene Hidalgo, Juan Delgado, Jr., Ruben Castillo, and Ray Hidalgo, by being leader of the gang giving the okay to commit the offense, by planning the offense, by ordering gang members to commit the offense, by calling Creeper to bring the weapons, by selecting certain gang members to participate in the offense, by gathering the gang members at Juanon's house, by planning to approach the victims' location from the empty field north of the victims' location, by explaining the victims' location to the group, by calling Bones to participate, by calling Ram to participate, by calling Rick to participate, by calling Kito to participate, by calling Perro to participate, by calling Little Sal to participate, by calling Marcial to participate, by arranging transportation to and from the victims' location, by driving participants to the victims' location, or by driving participants from the victims' location, then you will find the Defendant, HUMBERTO GARZA, guilty of the offense of Murder. 12 This quoted instruction is worded exactly as it appears in the Count One charge. There are a few minor grammatical variations in the Count Two charge.

With regard to Count One, the jury found appellant guilty of the lesser-included offense of murder and assessed a life sentence. With regard to Count Two, the jury found appellant guilty of capital murder, and the trial court sentenced appellant to death. The double-jeopardy clause protects against multiple prosecutions for the same offense following acquittal or conviction. 13 It also protects against multiple punishments for the same offense. 14 Here, the "multiple prosecutions" aspect is not implicated because appellant was convicted and sentenced in a single proceeding. 15 Thus, we are concerned only with the "multiple punishments" aspect in this case. 16 A multiple-punishments claim can arise in two contexts: (1) the lesser-included-offense context, in which the same conduct is punished twice-once for the basic conduct, and a second time for that same conduct plus more; and (2) punishing the same criminal act twice under two distinct statutes when the legislature intended the conduct to be punished only once. 17

13 Villanueva v. State, 227 S.W.3d 744, 747 (Tex. Crim. App. 2007) (citing Ex parte Kopecky, 821 S.W.2d 957, 958 (Tex. Crim. App. 1992)). 14 Id. 15 See id. 16 We recently addressed a "multiple punishments" double-jeopardy claim for one of appellant's co-defendants. Ramirez v. State, No. AP-75,167, 2007 Tex. Crim. App. Unpub. LEXIS 610 (Tex. Crim. App. Dec. 12, 2007) (not designated for publication). Ramirez was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death in two separate counts. In Ramirez, as in the present case, one count alleged murder in the course of robbery under Section 19.03(a)(2) and one count alleged the murders of more than one person during the same criminal transaction under Section 19.03(a)(7). 2007 Tex. Crim. App. Unpub. LEXIS 610 at *15. In Ramirez and in this case, both counts arose from the same conduct on the same date involving the same victims. Id. We held in Ramirez that the same evidence that formed the basis for "the same criminal transaction" element in one count also formed the basis for the robbery element in the other count and that there was only one "allowable unit of prosecution" under the statute in that circumstance. 2007 Tex. Crim. App. Unpub. LEXIS 610 at *15. We held that Ramirez had been subjected to multiple punishments for the same offense in violation of double-jeopardy, and we reversed his conviction and vacated his death sentence on one of the counts. 2007 Tex. Crim. App. Unpub. LEXIS 610 at *15. 17 Langs v. State, 183 S.W.3d 680, 685 (Tex. Crim. App. 2006).

In this case, the application paragraphs for the lesser-included offense of murder in Count One and Count Two were the same. Thus, the same conduct was punished twice: first in Count One for the "basic conduct" of murder and a second time in Count Two for "that same conduct plus more." It is clearly apparent from the face of the record that appellant was subjected to multiple punishments for the same offense in violation of the federal and state constitutional protections against double-jeopardy. And because both convictions arise out of the same trial, enforcement of the usual rules of procedural default would serve no legitimate state interest. 18 Thus, we will sustain appellant's first point of error. When a defendant is convicted of two offenses that are the "same" for double- jeopardy purposes, the "most serious" offense is retained and the other conviction is set aside. 19 The "most serious" offense is generally the offense of conviction for which the greatest sentence was assessed. 20 Here, the most serious offense is appellant's capital murder conviction in Count Two, for which he received the death sentence. Thus, we retain appellant's capital murder conviction and death sentence in Count Two. 21

18 Johnson v. State, 208 S.W.3d 478, 510 (Tex. App.-Austin 2006, pet. ref'd); Honeycutt v. State, 82 S.W.3d 545, 547 (Tex. App.-San Antonio 2002, pet. ref'd). 19 Ex parte Cavazos, 203 S.W.3d 333, 337 (Tex. Crim. App. 2006). 20 Id. at 338. 21 Appellant's appeal from his murder conviction and life sentence in Count One, Garza v. State, No. 13-05-00397-CR, is currently pending in the Thirteenth Court of Appeals. Because appellant's capital murder conviction and death sentence in Count Two is retained as "the most serious offense," the Thirteenth Court of Appeals may consider reversing appellant's murder conviction on double-jeopardy grounds.

In point of error two, appellant argues that the trial court "erred in imposing death as a sentence where the jury returned verdicts of both not guilty and guilty of capital-murder, under the same factual basis." In point of error three, he complains that the charge and verdict form failed to inform the jurors "whether a murder of more than one person in the same transaction would include a murder in the course of a robbery." Appellant's arguments are based on the faulty premise that his murder conviction in Count One amounted to an acquittal of the capital-murder alleged in Count Two. Appellant also asserts that "the Eighth Amendment requires that it be the death verdict that is set aside." As we have already stated, when a defendant is convicted of two offenses that are the "same" for double-jeopardy purposes, the "most serious" offense is retained and the other conviction is set aside. 22 The "most serious offense" test is not an "arbitrary rule," as appellant argues. One reason that we apply the "most serious offense" test to double- jeopardy violations is to eliminate arbitrariness in determining "greater" and "lesser" offenses. 23 Because appellant's points of error two and three are without merit, we overrule them.

22 Cavazos, 203 S.W.3d at 337. 23 Bigon v. State, S.W.3d , , Nos. PD-1769-06 & PD-1770-06, 252 S.W.3d 360, 2008 Tex. Crim. App. LEXIS 1, at *30-31 (Tex. Crim. App. Jan. 16, 2008). In point of error four, appellant claims that counsel "failed to preserve his right (1) not to be twice placed in jeopardy for the same offense; (2) to have his guilt case decided by jurors who were informed that the second count of the indictment was included in the first; and (3) to have his acquittal of capital-murder [in Paragraph 1 of the indictment] given preclusive effect over the later conviction [in Paragraph 2 of the indictment] for the same offense." However, we have already agreed with appellant's double-jeopardy argument, and he does not provide any additional argument or authorities to support an argument that his trial counsel were ineffective under the second and third prongs of his claim. These additional claims are inadequately briefed. 24 Point of error four is overruled.

24 See Tex. R. App. P. 38.1.

In point of error six, appellant asserts that he received ineffective assistance of counsel during voir dire. He specifically focuses on the veniremembers who were selected to serve on the jury, arguing that counsel failed to "diligently question [them] about their position, thoughts and feelings about the death penalty for any murder, let alone multiple murder." He also complains that defense counsel failed to ask them if they "could consider a life sentence as the proper punishment for the murder of more than one person in the same transaction." He asserts that "the result of the punishment phase of the trial [was] unreliable" because "the jury members' thoughts and feelings about the death penalty were either unknown, or were so biased in favor of the prosecution, the result of their deliberations was a foregone conclusion." To prevail on a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel, appellant must show (1) deficient performance and (2) prejudice. 25 "Judicial scrutiny of counsel's performance must be highly deferential." 26 To show deficient performance, the defendant must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that his counsel's representation fell below the standard of professional norms. 27 To demonstrate prejudice, the defendant must show a reasonable probability that, but for counsel's unprofessional errors, the result of the proceeding would have been different. 28

25 Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 687, 104 S. Ct. 2052, 80 L. Ed. 2d 674 (1984). 26 Id. at 689. 27 Id. at 688. 28 Id. at 694.

A Strickland claim must be firmly founded in the record, and the record must affirmatively demonstrate its meritorious nature. 29 Direct appeal is usually an inadequate vehicle for raising a Strickland claim because the record is generally undeveloped. 30 This is especially true in terms of deficient performance, where counsel's reasons for doing or failing to do something do not appear in the record. 31 Trial counsel should ordinarily be afforded an opportunity to explain his actions before being found ineffective. 32 Absent such an opportunity, the reviewing court should not find deficient performance unless the challenged conduct was so outrageous that no competent attorney would have engaged in it. 33

29 Goodspeed v. State, 187 S.W.3d 390, 392 (Tex. Crim. App. 2005). 30 Id. 31 Id. 32 Id. 33 Id.

Each prospective juror was asked in the jury questionnaire to categorize and explain his or her feelings about the death penalty, and the State and defense counsel asked some of them to elaborate during voir dire. The State consistently asked prospective jurors if they could consider the full range of punishment, and defense counsel consistently asked them if they were predisposed on punishment because there were multiple victims. The record also reflects that defense counsel often conferred with appellant before deciding not to challenge prospective jurors. Defense counsel could have had valid strategic reasons for conducting the voir dire as they did. We refuse to speculate about defense counsels' possible voir dire strategy, and we cannot conclude that their conduct was so outrageous that no competent attorney would have engaged in it. 34

34 See Goodspeed, 187 S.W.3d at 392-94 (holding that counsel's failure to ask any questions during voir dire could not be treated as ineffective assistance without inquiry into reasons for the conduct).

Appellant has also failed to demonstrate prejudice. The result of the jury's deliberations was not "a foregone conclusion," given that it found him guilty of the lesser-included offense of murder and assessed a life sentence in Count One. Point of error six is overruled. In point of error five, appellant claims that the trial court was biased against him because, after allowing defense counsel to conduct an inadequate voir dire, it seated a "biased jury which was unable to consider life imprisonment as a proper punishment." However, as discussed above, the jurors consistently answered during voir dire that they could consider the full range of punishment and that they were not predisposed on punishment because there were multiple victims. Buried within point of error five in his brief is appellant's claim that the trial court was biased because it allowed defense counsel to proceed to trial without retaining any experts. He alleges that "[b]y sanctioning Defense Counsel's neglect, with regard to defense experts, the Court helped create an unfair trial for [appellant]." 35

35 We understand appellant to be raising this issue solely in terms of trial-court bias, not as a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel. To the extent that he is attempting to raise a Strickland argument, his claim is multifarious and inadequately briefed. Tex. R. App. P. 38.1

During pre-trial proceedings on February 10, 2005, the State informed the trial court that defense counsel had not provided "notice of experts" as requested. The following exchange occurred: Court: They are requesting your list. Defense Counsel: I don't have experts. I'm not going to have any experts. Court: You are not going to be calling anybody? Defense Counsel: No, sir. The trial court then asked the parties to approach the bench for an off-the-record discussion. We do not know the substance of that conversation, and the matter was not mentioned again. Absent a clear showing of bias, a trial court's actions will be presumed to have been correct. 36 Appellant has not made a clear showing of trial-court bias. Point of error five is overruled.

36 Brumit v. State, 206 S.W.3d 639, 645 (Tex. Crim. App. 2006).

In point of error seven, appellant complains about the capital-murder application paragraph in the Count Two jury charge. He alleges that (1) he was denied his right to the presumption of innocence, (2) the State was relieved of its burden to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt, and (3) the language in the application paragraph "conveyed to the jury the court's opinion on the merits of the case." The jury charge in Count Two defined capital-murder as murder "in the course of committing or attempting to commit the offense of Robbery." 37 The capital-murder application paragraph contained two alternative theories of liability, the first authorizing the jury to convict appellant as a party under Section 7.02(a) , and the second authorizing the jury to convict appellant as a conspirator under Section 7.02(b). The "party" portion required the jury to find that the co-defendants "intentionally and knowingly cause[d] the deaths" of the victims "by shooting them with a firearm" and that one or more of the co-defendants "were then and there in the course of committing or attempting to commit the offense of robbery" of the victims. It authorized the jurors to convict appellant as a party if they found that . . . the Defendant, HUMBERTO GARZA, then and there knew of the intent, if any, of one or more of the said CO-DEFENDANTS, to rob the said JIMMY ALMENDARIZ, JUAN DELGADO, III, JERRY EUGENE HIDALGO, JUAN DELGADO, JR., RUBEN CASTILLO, and RAY HIDALGO, and the Defendant acted with intent to promote or assist the commission of the offense by one or more of the said CO-DEFENDANTS by encouraging, directing, aiding, or attempting to aid one or more of the said CO-DEFENDANTS, to commit the offense of Murder of the said JIMMY ALMENDARIZ, JUAN DELGADO, III, JERRY EUGENE HIDALGO, JUAN DELGADO, JR., RUBEN CASTILLO, and RAY HIDALGO, by being leader of the gang giving the okay to commit the offense, by planning the offense, by ordering gang members to commit the offense, by calling Creeper to bring the weapons, by selecting certain gang members to participate in the offense, by gathering the gang members at Juanon's house, by planning to approach the victims' location from the empty field North of the victims' location, by explaining the victims' location to the group, by calling Bones to participate, by calling Ram to participate, by calling Rick to participate, by calling Kito to participate, by calling Perro to participate, by calling Little Sal to participate, by calling Marcial to participate, by arranging transportation to and from the victims' location, by driving participants to the victims' location, or by driving participants from the victims' location . . .

37 Tex. Penal Code § 19.03(a)(2).

In contrast, the "conspiracy" portion required the jury to find that the co-defendants "entered into a conspiracy to rob" the victims "and that pursuant thereto did carry out, or attempt to carry out, such conspiracy to rob" the victims "in that . . . in the course of committing theft of personal property" from the victims "to-wit, money, jewelry, drugs, a cell phone, or personal papers, and with intent to obtain or maintain control of said property" the co-defendants "intentionally caused bodily injury" to the victims "to-wit, death, by shooting" the victims "with a firearm or firearms, intending thereby to kill" the victims. 38 It authorized the jurors to convict appellant as a conspirator if they found that. . . the Defendant, HUMBERTO GARZA, pursuant to said conspiracy, if any, with the intent to promote and assist [CO-DEFENDANTS] in the commission of said robbery, if any, was acting with and aiding one or more of the said CO-DEFENDANTS in the execution or attempted executions of said robbery of the said JIMMY ALMENDARIZ, JUAN DELGADO, III, JERRY EUGENE HIDALGO, JUAN DELGADO, JR., RUBEN CASTILLO, and RAY HIDALGO, if any, and that the shooting of the said JIMMY ALMENDARIZ, JUAN DELGADO, III, JERRY EUGENE HIDALGO, JUAN DELGADO, JR., RUBEN CASTILLO, and RAY HIDALGO followed in the execution of the conspiracy, if any, of HUMBERTO GARZA and one or more of the said CO-DEFENDANTS to rob the said JIMMY ALMENDARIZ, JUAN DELGADO, III, JERRY EUGENE HIDALGO, JUAN DELGADO, JR., RUBEN CASTILLO, and RAY HIDALGO of his property, and that the shooting of the said JIMMY ALMENDARIZ, JUAN DELGADO, III, JERRY EUGENE HIDALGO, JUAN DELGADO, JR., RUBEN CASTILLO, and RAY HIDALGO by one or more of the said CO-DEFENDANTS, if there was such, was done in furtherance of the conspiracy to rob the said JIMMY ALMENDARIZ, JUAN DELGADO, III, JERRY EUGENE HIDALGO, JUAN DELGADO, JR., RUBEN CASTILLO, and RAY HIDALGO, if any, and was an offense that should have been anticipated as a result of the carrying out of the conspiracy . . .

38 The conspiracy portion adds another co-defendant: Jeffrey Juarez a/k/a "Dragon."

The general verdict form did not require the jury to specify which theory of party liability it relied upon. 39

39 The verdict form stated: "We, the Jury, find the Defendant, HUMBERTO GARZA, GUILTY of the offense of Capital-murder as charged in the indictment."

Appellant asserts that "the trial court submitted [the] conspiracy theory to the jury in such a way that he could be convicted of capital-murder under circumstances not giving rise to the anticipation that human life would be taken." He claims that "the jurors likely thought this application paragraph was satisfied if the offense that was or should have been anticipated was the shooting of the six named persons, not necessarily the killing of them." When we review a charge for alleged error, we must examine the charge as a whole instead of a series of isolated and unrelated statements. 40 The charge stated that the co-defendants' "shooting" of the victims was done in furtherance of the conspiracy to rob and was an offense that should have been anticipated as a result of carrying out the conspiracy. We do not view this statement in isolation. The charge also stated that the co-defendants "intentionally caused bodily injury" to the victims, "to-wit, death, by shooting" them "with a firearm or firearms, intending thereby to kill" them. Thus, the "shooting" offense that appellant should have anticipated as a result of carrying out the conspiracy was the co-defendants' shooting the victims to death with the intent to kill them. There is no reasonable likelihood that the jury applied the challenged instruction in an erroneous way. 41 Appellant also contends that the trial court commented on the weight of the evidence by "stating as established fact matters that were elements for the State to prove." He argues that the long list of specific acts in the "party" portion of the charge was unnecessary and called undue attention to the State's theory of the case. He complains about the inconsistent use of the phrase "if any," arguing that its omission in certain places suggested "established facts." He further asserts that the inclusion of the co-defendants' "alias nicknames" was "suggestive of prior criminal activity and predisposition." In sum, he argues: "[B]y telling the jury that [appellant] was the leader of a group of criminals that had done a series of acts resulting in the deaths of six named persons, the court sent the message that the prosecution had proved their case and that the inevitable verdict was 'guilty.'" We disagree.

40 Dinkins v. State, 894 S.W.2d 330, 339 (Tex. Crim. App. 1995). 41 Boyde v. California, 494 U.S. 370, 380, 110 S. Ct. 1190, 108 L. Ed. 2d 316 (1990).

The language in the capital-murder application paragraph tracked the statutory language contained in Sections 7.02(a) and 7.02(b). Appellant's gang membership was raised by the evidence. The gang names and activities detailed in the charge reflected the State's theory; however, the inclusion of these details did not endorse that theory, nor were they presented as "established facts." The jurors were clearly instructed to find appellant guilty of capital-murder only if they found the stated elements "from the evidence beyond a reasonable doubt." The wording of the charge was not an improper comment on the weight of the evidence. Point of error seven is overruled. In point of error eight, appellant argues that Apprendi and Ring 42 mandate that future-dangerousness "must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt, rather than by the current statutory requirement of a 'probability' of future-dangerousness beyond a reasonable doubt, which is a much lower standard." In points of error nine and ten, he argues that Article 37.071 violates due process and amounts to cruel and unusual punishment. He asserts that the misleading use of the undefined term "probability" permits the jury to find future-dangerousness based on a standard less than "beyond a reasonable doubt."

42 Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466, 120 S. Ct. 2348, 147 L. Ed. 2d 435 (2000); Ring v. Arizona, 536 U.S. 584, 122 S. Ct. 2428, 153 L. Ed. 2d 556 (2002).

We have previously upheld the constitutionality of Article 37.071 when faced with these arguments. 43 Apprendi and Ring have no applicability to Article 37.071 in its current form. 44 The inclusion of the term "probability" does not render the future-dangerousness special issue unconstitutional. 45 The State must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that there is a probability that the defendant will be a continuing threat to society. 46 This is constitutionally sufficient. 47 Points of error eight, nine, and ten are overruled.

43 Rayford v. State, 125 S.W.3d 521, 534 (Tex. Crim. App. 2003). 44 Id. 45 Id. 46 Id. 47 Id.

In points of error eleven and twelve, appellant contends that Article 37.071 violates the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution "by instructing jurors to decide the likelihood of [appellant's] future-dangerousness through a vague definition of 'continuing threat to society.'" We have held that the reference to the statutory term "society" is not unconstitutionally vague and that the jury is presumed to understand it without an instruction. 48 Appellant has not persuaded us to overrule our precedent. Points of error eleven and twelve are overruled.

48 Murphy v. State, 112 S.W.3d 592, 606 (Tex. Crim. App. 2003).

In points of error thirteen, fourteen, and fifteen, appellant challenges the version of Article 37.071 under which he was sentenced because it failed to provide the jury with the option to sentence him to life without parole. He asserts that the statute amounts to cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment and offends his rights to due process and equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment. We have previously denied such claims, 49 and appellant fails to persuade us that our prior holding is incorrect. Points of error thirteen, fourteen, and fifteen are overruled.

49 Arnold v. State, 873 S.W.2d 27, 39-40 (Tex. Crim. App. 1993).

In points of error sixteen and seventeen, appellant argues that the evidence is legally and factually insufficient to support the jury's affirmative finding on the future-dangerousness special issue. In points of error eighteen and nineteen, appellant contends that the trial court violated the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments by sentencing him to death without legally or factually sufficient evidence of future-dangerousness. We do not conduct factual sufficiency reviews of the future-dangerousness special issue. 50 In evaluating legal sufficiency, we view the evidence in the light most favorable to the jury's finding and determine whether any rational trier of fact could have found beyond a reasonable doubt that there is a probability that appellant would commit criminal acts of violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society. 51

50 McGinn v. State, 961 S.W.2d 161, 169 (Tex. Crim. App. 1998). 51 Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307, 99 S. Ct. 2781, 61 L. Ed. 2d 560 (1979).

The State presented evidence at the guilt phase that appellant, although not a "triggerman," was a gang leader who planned and orchestrated the brutal killings of six rival gang members. 52 At punishment, the State also presented evidence of appellant's prior criminal history. Appellant committed the offense of unauthorized use of a motor vehicle at age fifteen and was placed on probation. He was later committed to TYC after violating the conditions of his probation. He was released on parole shortly thereafter. In July 1991, just a few days before his seventeenth birthday, he committed the offense of attempted murder when he stabbed a man during an altercation. On September 10, 1991, he was certified to be tried as an adult for that offense. On September 25, 1991, he committed burglary of a habitation. He pleaded guilty to both offenses in 1992 and was sentenced to eighteen years in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). He committed several disciplinary offenses while incarcerated in TDCJ, including getting into a fist fight with one inmate and stabbing another inmate with a homemade weapon. He was released on parole in April 2002 and committed the instant offense in January 2003. This evidence, viewed in the light most favorable to the jury's finding, was sufficient to support the jury's affirmative answer to the future-dangerousness special issue. Points of error sixteen, seventeen, eighteen, and nineteen are overruled.

52 In its determination of the future-dangerousness special issue, the jury is entitled to consider all of the evidence presented at both the guilt and punishment stages of trial. Druery v. State, 225 S.W.3d 491, 507 (Tex. Crim. App.), cert. denied, 128 S. Ct. 627, 169 L. Ed. 2d 404 (2007). In point of error twenty, appellant claims that Article 37.071 violates the Fourteenth Amendment by implicitly placing the burden on the defendant to prove mitigation, rather than requiring the jury to make a finding against the defendant on that issue beyond a reasonable doubt. He also asserts that the aggravating factor of future-dangerousness must be alleged in the indictment before the State can seek the death penalty. In support of these claims, he cites Apprendi, Ring, and Blakely v. Washington. 53 We have previously rejected these claims, 54 and appellant does not persuade us that our prior cases were wrongly decided. Point of error twenty is overruled.

53 542 U.S. 296, 124 S. Ct. 2531, 159 L. Ed. 2d 403 (2004). 54 Roberts v. State, 220 S.W.3d 521, 535 (Tex. Crim. App.), cert. denied, 128 S. Ct. 282, 169 L. Ed. 2d 206 (2007); Renteria v. State, 206 S.W.3d 689, 709 (Tex. Crim. App. 2006); Jones v. State, 119 S.W.3d 766, 791 (Tex. Crim. App. 2003).

In points of error twenty-one through twenty-six, appellant argues that Article 37.071 violates the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution. He claims that the mitigation special issue "forces jurors to weigh the aggravating circumstances against mitigating circumstances," and, as a result, it "does not provide a means for jurors to give effect to the mitigating circumstances warranting a life sentence," it "shifts the burden of proof to the defendant to prove that sufficient mitigating circumstances exist to warrant a life sentence," and it "does not require jurors to consider mitigating circumstances alone in determining whether a life sentence is warranted." The jury's consideration of aggravating circumstances in deliberating on the mitigation issue is permitted, but not required. 55 Article 37.071 does not shift the burden of proof to the accused to prove a mitigating circumstance. 56 We have consistently declined to hold Article 37.071 unconstitutional for failing to assign a burden of proof on the mitigation special issue. 57 Points of error twenty-one through twenty-six are overruled.

55 Hankins v. State, 132 S.W.3d 380, 385 (Tex. Crim. App. 2004); Mosley v. State, 983 S.W.2d 249, 263 n.18 (Tex. Crim. App. 1998). 56 Threadgill v. State, 146 S.W.3d 654, 672 (Tex. Crim. App. 2004). 57 Russeau v. State, 171 S.W.3d 871, 886 (Tex. Crim. App. 2005), cert. denied, 548 U.S. 926, 126 S. Ct. 2982, 165 L. Ed. 2d 989 (2006); Resendiz v. State, 112 S.W.3d 541, 549-50 (Tex. Crim. App. 2003).

In points of error twenty-seven through twenty-nine, appellant argues that Article 37.071 violates the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments "by failing to provide for any meaningful appellate review of the mitigation special issue in the punishment phase of the trial." We have previously rejected this claim. 58 Points of error twenty-seven through twenty-nine are overruled.

58 Renteria, 206 S.W.3d at 707; Russeau, 171 S.W.3d at 886.

In points of error thirty through thirty-three, appellant raises several challenges to the "10-12 rule." Art. 37.071, § 2(d) and § 2(f). He argues that the trial court should have instructed the jury that a single holdout juror on any special issue would result in an automatic life sentence. He asserts that the trial court's failure to do so amounted to cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment, denied him due process under the Fourteenth Amendment, and denied him a fair and impartial jury and effective assistance of counsel under the Sixth Amendment.

We have consistently upheld the "10-12 rule" as constitutional. 59 The instructions on answering the special issues do not mislead the jury into thinking that an affirmative answer should be given unless ten or more jurors agree to give a negative one. 60 Any juror who wishes to vote for life contrary to the votes of the majority is given an avenue to accommodate the complained-of potential disagreements, "for every juror knows that capital punishment cannot be imposed without the unanimous agreement of the jury on all three special issues." 61 The "10-12 rule" ensures the proper level of juror deliberation. 62 It serves this value by not informing the jury of the consequences of a non-verdict, while at the same time ensuring that the death penalty will not be imposed without the unanimous consent of the jury. 63 Points of error thirty through thirty-three are overruled.

59 Prystash v. State, 3 S.W.3d 522, 536 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999); McFarland v. State, 928 S.W.2d 482, 519 (Tex. Crim. App. 1996); Lawton v. State, 913 S.W.2d 542, 558-59 (Tex. Crim. App. 1995). 60 Prystash, 3 S.W.3d at 536. 61 Id. (quoting Lawton v. State, 913 S.W.2d 542, 559 (Tex. Crim. App. 1995)). 62 Id. at 537. 63 Id.

We affirm the trial court's judgment and sentence of death in Count Two.

Garza v. State, 213 S.W.3d 338 (Tex.Crim.App. 2007). (Direct Appeal)

PROCEDURAL POSTURE: In the 398th Judicial District Court Hidalgo County, Texas, appellant was convicted of two counts of capital murder under Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 19.03(a), and sentenced to death. He was also convicted and sentenced to death for engaging in organized criminal activity under Tex. Penal Code Ann. Code § 71.02. This appeal followed.

OVERVIEW: Appellant's contention that the evidence was insufficient to support his capital murder convictions was rejected on appeal. Appellant admitted in his statement to police that he and three other men carried out "a hit" which resulted in four women's deaths. Forensic evidence corroborated the statement. While the State's evidence did not affirmatively show that appellant fired the fatal shots, the evidence established his participation in the offense as a party. The record also supported the findings regarding the voluntariness of appellant's statement. There was no abuse of discretion in requiring appellant to display his tattoos to the jury because the tattoos were admissible to prove the "criminal street gang" element of the offense, and their probative value was not outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice. And, finally, the jury was properly instructed that it could convict and punish appellant for both capital murder and engaging in organized criminal activity by committing capital murder as a criminal street gang member, but the death sentence for violating Tex. Penal Code Ann. Code § 71.02 was erroneous since appellant should have been sentenced as a first-degree felon.

OUTCOME: Appellant's conviction and death sentence for capital murder under Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 19.03 was affirmed, but the death sentence for organized criminal activity under Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 71.02 was vacated and the matter was remanded to the trial court for resentencing appellant as a first-degree felon.

JUDGES: PRICE, J., delivered the opinion of the Court in which KELLER, P.J., and MEYERS, JOHNSON, KEASLER, HERVEY, HOLCOMB, and COCHRAN, JJ., joined. WOMACK, J., dissented.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

On the evening of September 4, 2002, Maria De La Luz Bazaldua Cobarrubias, Danitzene Lizeth Vasquez Beltran, Celina Linares Sanchez, Lourdes Yesenia Araujo Torres, Karla Espino Ramos, and Magda Torres Vasquez were working at Garcia's Bar in Donna, Texas. When the bar closed at midnight, Cobbarubias gave the other women a ride to their trailer home. She drove south on Business 83, turned onto Valley View Road, and then parked close to the women's trailer. Before anyone had a chance to get out of the vehicle, shots were fired. Cobbarubias, Beltran, Sanchez, and Torres sustained multiple gunshot wounds and died from their injuries. Ramos sustained gunshot wounds to her arm and leg, but survived. Vasquez did not sustain any physical injuries.