35th murderer executed in U.S. in 2013

1355th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Missouri in 2013

69th murderer executed in Missouri since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(35) |

Joseph Paul Franklin a/k/a James Clayton Vaughn, Jr W / M / 27 - 63 |

Gerald Gordon W / M / 42 |

Summary:

Believing that Jews were “enemies of the white race,” Franklin drove to Dallas, Texas after robbing a bank in Little Rock, Arkansas. In Dallas, Franklin bought a 30-06 rifle with a telescopic sight. He then drove to St. Louis, Missouri, checked into a hotel, scouted the city for synagogues, and finally chose Brith Shalom Kneseth Israel Congregation in Richmond Heights. When people emerged from the synagouge, Franklin began firing from 100 yards away, shooting five times. Gerald Gordon was killed and Steven Goldman and William Ash were wounded. He rode a bicycle from the scene to a parking lot, where he drove away. Franklin was convicted of killing eight people in the late 1970s and 1980s in racially motivated attacks around the country. He finally stumbled after the Utah murders in August 1980. He was arrested a month later in Kentucky, briefly escaped, and was recaptured later in Florida. The crimes remained unsolved for seventeen years. While serving a life sentence for the murders in Utah, in 1994, Franklin confessed to the 1977 St. Louis synagogue shootings. Franklin gave the FBI agent and local police a detailed account of his preparation for and execution of the shootings.

Franklin faced a marathon series of state and federal trials, with mixed results. In 1982, he was acquitted of federal civil rights charges in the May 1980 shooting that left civil rights leader Vernon Jordan critically injured in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Utah juries found him guilty of murder and civil rights violations; Franklin was serving life on those counts in 1983 when he confessed the 1978 sniping that crippled Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flint in Gwinnett County, Georgia. Franklin was indicted for that crime but never tried. More convictions followed: for the Chattanooga bombing; for the double murder in Wisconsin, for the murder of Gerald Gordon, killed leaving a Clayton, Missouri synagogue in 1977; for the June 1980 double murder in Cincinnati; for the 1978 murder of William Tatum, shot while talking to a white woman outside a Chattanooga restaurant. Other crimes confessed by Franklin without further convictions include the 1980 murder of teenager Nancy Santomero at a peace retreat in West Virginia; the 1980 murders of an interracial couple in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; the 1980 murders of an interracial couple in Johnstown, Ohio; and the separate 1979 murders of a white woman and a black man in Decatur, Georgia. Overall, investigators believe Franklin is responsible for at least 18 murders and five nonfatal shootings in 11 states, plus two bombings and 16 bank robberies.

Citations:

State v. Franklin, 969 S.W.2d 743 (Mo. 1998). (Direct Appeal)

Franklin v. State, 24 S.W.3d 686 (Mo. 2000). (PCR)

State v. Franklin, 714 S.W.2d 252 (Tenn. 1986).

State v. Franklin, 735 P.2d 34 (Utah 1987).

Final Meal:

Franklin did not eat a final meal before his death, preferring to fast.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

State of Missouri v. Joseph P. Franklin

December 9, 2008 by smays

Executed November 20, 2013, 6:08 a.m.

DOB: 04-13-50

969 S.W.2d 743 (Mo.banc 1998)

Franklin Case Facts: In September of 1977, believing that Jews were “enemies of the white race,” Franklin drove to Dallas, Texas after robbing a bank in Little Rock, Arkansas. In Dallas, Franklin bought a 30-06 rifle with a telescopic sight. He then drove to St. Louis, Missouri, checked into a hotel, scouted the city for synagogues, and finally chose Brith Shalom Kneseth Israel Congregation in Richmond Heights.

To prepare for the crime, Franklin bought some ten-inch nails, a guitar case and a bicycle. He tested the bicycle to assure himself that it could be used to enable him to leave the scene of the crime. He drove the nails into a telephone pole to serve as a rifle rest. Later, he ground the serial number off the rifle. He then cleaned the rifle, ammunition and guitar case of any fingerprints and, thereafter, he used gloves to handle the equipment. Lastly, he put the rifle into the guitar case and hid them both in some bushes near the synagogue.

On October 8, 1977, Franklin waited outside the synagogue for people to emerge. Shortly before 1:00 p.m., some of the guests left the synagogue and walked toward their cars. Franklin began firing on the guests. He fired five shots from approximately one hundred yards. Gerald Gordon was shot in the left side of his chest and later died from blood loss resulting from damage to his lung, stomach, spleen, and other internal organs. Steven Goldman was grazed on the shoulder. William Ash was wounded in the left hand and later lost his small finger on that hand. Having fired all his ammunition, Franklin abandoned the rifle and the guitar case. He then rode his bicycle to a nearby parking lot where his automobile was parked, hid the bicycle in some bushes and left St. Louis by car. P>

Franklin execution: a timeline (AUDIO)November 20, 2013 By Jessica Machetta

Joseph Paul Franklin was to be executed at 12:01 a.m., Nov. 20, 2013. The Department of Corrections has until 11:59 p.m. to carry out the state’s orders, allowing time for any legal descrepancies to be resolved. Here’s a timeline of the last-hours efforts to block his execution and of the execution this morning at the Bonne Terre prison.

TUESDAY

4:28 p.m. – Federal Judges Nanette Laughry and Carol Jackson issue two stays of execution, after three appeals filed by Franklin’s attorney. One claimed he was mentally ill and should not be executed because of that, and the other challenged the drug protocol, a lethal dose of pentobarbital, which has never been used for an execution in Missouri. (Several other states have successfully used pentobarbital, which is commonly used to euthanize animals.)

10:30 p.m. — Members of the press and state witnesses are taken to separate holding rooms in the Bonne Terre correctional facility. Members of the press are only allowed to have a pen, notebook, and a watch. In the end, though, neither Franklin nor his victims will have witnesses for the execution.

WEDNESDAY

12:01 a.m. — No new information is available; prison officials stand by to carry out the execution despite the legal proceedings. Franklin remains in a holding cell.

1:30 a.m. (approximately) — Witnesses there for Franklin have left. Corrections staff tells members of the press that included Franklin’s daughter, two members of the clergy, and two witnesses from the Department of Corrections.

2:55 a.m. — Stays are vacated, Franklin appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court.

4:40 a.m. — Attorney General Chris Koster obtains reversal of appeals in 8th District Court of Appeals.

5:17 — Corrections staff tells press “it’s a go.” Superintendent Dave Dormire confirms, “It does appear the execution will proceed.”

5:20 — Dept. of Corrections Director George Lombardi comes in, reads statement thanking witnesses for their service to the state. Stresses that a lawful execution is about to take place. Dormire reads the protocol: 5 grams of pentobarbital is to be administered. If that does not result in death after 5 minutes, another 5 grams is to be administered. “The entire process should take 10 to 15 minutes.” He says he’ll be back to get the witnesses from the holding area soon.

6 a.m. — Corrections officials tell state witnesses and press it’s time to go to the execution chamber.

Six witnesses: three members of the press, and three private citizens, enter a darkened viewing area. A black curtain is covering a one-way window between them and Franklin. Dormire stands at the door. There is a guard on each side of the curtain.

6:07 — The drug is administered and the guards are ordered to open the curtain. Franklin is strapped onto a gurney, a white sheet pulled up to his chin. His hair is combed behind his ears and he is wearing his glasses. Other than the blinking of his eyes, there is no movement.

6:10 — Franklin’s chest rises and falls with a few deep breaths, he closes his eyes, and swallows. His chest stops rising and falling, it appears he has stopped breathing. His mouth falls open slightly, and his face begins to pale.

6:15 — The guards are ordered to pull the black curtain closed, so that medical staff can check Franklin’s vital signs. “Five grams of pentobarbital was administered,” says Dormire, “and we waited five minutes.”

6:17 — The black curtain opens, and a voice crackles over one of the guards radio’s … “execution complete.” The warden signs the death warrant and slides it under the door.

"Missouri executes white supremacist Joseph Paul Franklin," by Jeremy Kohler. (Nov 20, 2013 10:45 am )

BONNE TERRE, Mo. • Missouri has executed Joseph Paul Franklin, the white supremacist killer who targeted blacks and Jews during a multistate crime spree from 1977-1980. Franklin, 63, was put to death for the 1977 sniper killing of Gerald Gordon at a Richmond Heights synagogue. His fate was sealed when the U.S. Supreme Court, at about 5:20 a.m. Wednesday, upheld a federal appeals court decisions overturning stays granted Tuesday by federal judges in Jefferson City and St. Louis.

Mike O’Connell, of the Missouri Department of Public Safety, said the execution got the final OK from Gov. Jay Nixon at 6:05 a.m. By this time, Franklin was already strapped to a table in the state’s death chamber at Eastern Reception, Diagnostic and Correctional Center, ready for the injection. He received a lethal injection at 6:07 a.m., and his death was confirmed at 6:17 a.m. The execution was the first in Missouri using a single drug, pentobarbital. Three media witnesses said Franklin did not seem to express pain. He did not make any final written statement and did not speak a word in the death chamber. After the injection, he blinked a few times, breathed heavily a few times, and swallowed hard, the witnesses said. The heaving of his chest slowed, and finally stopped, they said.

Jessica Machetta, managing editor of Missourinet, who witnessed the execution, said he did not seem to take a breath after 6:10 a.m. Nixon said in a statement: “The cowardly and calculated shootings outside a St. Louis-area synagogue were part of Joseph Paul Franklin’s long record of murders and other acts of extreme violence across the country, fueled by religious and racial hate.” He asked that Gordon be remembered and that Franklin’s victims and their families remain in the thoughts and prayers of Missourians.

Judges in two U.S. court districts had ordered stays of execution for Franklin on Tuesday. But Missouri Attorney General Chris Koster’s office successfully appealed both of the orders to the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals. U.S. District Judge Nanette K. Laughrey in Jefferson City granted the first stay Tuesday afternoon. She criticized the state for changing the plan just days beforehand for how the execution was to be carried out — using a lethal injection of pentobarbital produced by a secret compounding pharmacy — and then telling the defendant that “time is up” to challenge the method.

Then, Tuesday night, U.S. District Judge Carol E. Jackson in St. Louis granted a second stay, based on Franklin’s claim that he is mentally incompetent to be executed. She wrote that Laughrey’s stay “does not moot the necessity to address the petitioner’s motion in this case.” Laughrey wrote that neither Franklin’s lawyers nor the court had been able to address the question of whether the state’s execution method passes constitutional muster, “because the Defendants keep changing the protocol that they intend to use.” Whether the use of pentobarbital constituted cruel and unusual punishment was among the issues raised in the request for a stay filed by Franklin and other plaintiffs. The stay was meant to “ensure that the Defendants’ last act against Franklin is not permanent, irremediable cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment,” Laughrey’s ruling said.

Last month, Gov. Jay Nixon delayed the execution of another man because of issues surrounding the state’s plan to use the widely used anesthetic propofol. Most of the supply of propofol comes from drug makers in the European Union, which opposes the death penalty and has said it would cut off supplies to the U.S. if the drug were used for executions. Nixon ordered the state to find a new drug, and the Department of Corrections settled on pentobarbital, which is commonly used to euthanize pets, to be provided by a compounding pharmacy. The name of that pharmacy is a secret, under a law passed by the Missouri Legislature that bans making public the identity of anyone on the execution team. “The Department has not provided any information about the certification, inspection, history, infraction history, or other aspects of the compounding pharmacy,” the judge’s order noted.

Koster’s office argued in a motion to vacate Laughrey’s order that “the use of sufficiently potent pentobarbital, in the dose planned, will lead to a rapid and painless death” and that the Supreme Court has said that some risk of pain is inherent in any method of execution. The office also argued that Franklin had not exhausted his administrative appeals, and thus had no right to relief from the court.

The plaintiff’s expert, the judge’s order said, noted that the American Veterinary Medical Association recently discouraged the use of compounded drugs such as pentobarbital because of the “high risk of contamination.” In the competency appeal, Jackson ruled that a stay was necessary to investigate a defense expert’s claim that Franklin was insane. She noted that he “has routinely stated that he makes decisions based on idiosyncratic associations of meaning to particular letters or numbers or messages he receives in dreams.” Koster’s office responded in a motion that said Jackson relied on anecdotes and abused her discretion. “There is nothing inherently delusional about these things. Many people are superstitious or ascribe meaning to the symbols in their dreams. None of the anecdotes shows Franklin does not have a rational understanding of the State’s basis for his execution, and the district court offered no explanation or analysis to the contrary.” The Missouri Supreme Court had denied Franklin’s appeals earlier Tuesday.

PROTEST HELD HERE

Franklin did not eat a final meal before his death, preferring to fast. In addition to the three media witnesses, six people witnessed the execution for the state. Franklin’s four witnesses left the prison about 4 a.m. and were not present for his death.

While prison guards cordoned off an area near the prison for demonstrators for and against the execution, none arrived. Protesters with Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty held a candlelight vigil on the steps of St. Francis Xavier (College) Church at St. Louis University on Tuesday night. About three dozen people stood in silence on the steps, holding battery-powered candles. Margaret Phillips, the St. Louis representative of the group, said Franklin’s mental illness and concerns about the origins of the death penalty drug troubled the group. They prayed for Franklin’s family and his victims. “Even though we oppose the death penalty, we don’t support his actions, at all,” she said. The Associated Press and Valerie Schremp Hahn of the Post-Dispatch contributed to this report.

"Up next for execution: The man who shot Larry Flynt and Vernon Jordan," by by Jeremy Kohler (11-17-13)

The next U.S. execution is scheduled for 12:01 a.m. Wednesday in Bonne Terre, Mo. If the execution survives legal challenges filed in federal and state courts, it will be watched closely because of the high profile of the condemned inmate and the state’s controversial method to kill him.

Joseph Paul Franklin, 63, is condemned to die for the 1977 sniper killing of Gerald Gordon, 42, the father of three young daughters, outside a Richmond Heights synagogue. Authorities have convicted the avowed racist of, or linked him to, 18 killings and other crimes, including the murder of two black men in Utah, two black teens in Ohio and an interracial couple in Wisconsin. He admitted to the nonfatal shootings of Hustler Magazine publisher Larry Flynt and civil rights leader Vernon Jordan, but was never convicted of those crimes.

For several years, Missouri was one of the nation’s most prolific death penalty states, but the pace of the state’s executions has slowed to a crawl because of constitutional challenges, questions about the fitness of its execution team and, most recently, struggles to secure lethal drugs for executions. The state executed 66 prisoners between 1989 and 2005, but just two in the past eight years, and no one since Martin Link in February 2011.

Now, Missouri says it is prepared to give Franklin a lethal injection of pentobarbital, a drug commonly used to euthanize pets, produced by a compounding pharmacy. Franklin’s attorneys are appealing to state and federal courts to stop the execution, arguing that the method would put him at risk of an unconstitutionally “excruciatingly painful execution.” And death penalty opponents are attacking Missouri’s secrecy over the people involved. Flynt on Nov. 8 filed a motion in federal court to unseal documents revealing the identity of an anesthesiologist on the team. “There are simply too many unanswered questions to justify ending someone’s life,” Jeffrey A. Mittman, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri, wrote in an email to ACLU supporters on Friday.

Lee Lankford was a sergeant with Richmond Heights police when the shootings happened, and was a captain in 1980 when he figured out that Franklin was the killer. He scoffed at the concern over Franklin’s comfort. “How many lives did he take on his rampage across the United States?” Lankford, who retired as Richmond Heights police chief in 1992, said on Friday. “Just to be put to sleep, that’s the easiest way out of here.”

Major drug manufacturers have stopped supplying drugs used in executions. Stymied by a shortage of chemicals available for the state’s long-used three-drug sequence, Missouri last year switched to a lethal dose of propofol. It would have been the first time the common hospital anesthetic was used in an execution. The European Union, which opposes the death penalty, had threatened to cut off supplies of the drug to the U.S. if the execution went forward, which could have had a widespread impact on hospitals. Last month, Gov. Jay Nixon postponed the execution of Allen Nicklasson after the Department of Corrections was pressured to return its propofol inventory. Within days, Missouri announced it would use a different drug for Franklin’s execution.

The state has added the compounding pharmacy to its execution team to produce a lethal injection of pentobarbital. Just a half-dozen states have resorted to compounding pharmacies. Those pharmacies come under limited government oversight, and their safety has come into question. Earlier this year, federal regulators said they had found numerous unsafe practices at 30 compounding pharmacies. Last year, more than 50 people died and more than 600 were made ill from fungal meningitis after receiving injections of a contaminated steroid made by the New England Compounding Center.

AN AIM TO KILL JEWS

Franklin has caused more than his share of suffering. In a 1995 interview with two Post-Dispatch reporters, Franklin, who legally changed his name to honor Nazi propagandist Joseph Paul Goebbels, said he randomly picked St. Louis from a road map as a site for killing “as many Jews as I could.” He used a phone book to select Brith Sholom Kneseth Israel Congregation in Richmond Heights.

On Oct. 7, 1977, a Friday, Franklin arrived in St. Louis and chose a place for the shooting, from a knoll overlooking the synagogue. He returned about 9 a.m., on the Sabbath. A bar mitzvah was under way. He fired five shots, killing Gordon. In the shooting, another man lost a finger and was wounded in the hip. A bullet ripped through the clothes of a third man. Franklin escaped to Memphis, Tenn. “As soon as they came out, I opened fire,” he said. “I hit two … I wanted to kill at least two of them. After the first two shots, I fired three quick shots randomly at the synagogue.”

Franklin told the Post-Dispatch that he discovered Nazism through pamphlets he read. He later joined the Ku Klux Klan, the American Nazi Party and the National States Rights Party. He decided to act after he moved to the Washington area in the early 1970s. The moment came one Saturday in 1975 as he walked past a synagogue in Maryland. “I remember thinking I could just sit there with a rifle and pick off Jews,” he said.

His next attack was in Chattanooga, Tenn., in July 1977, where he blew up a synagogue. The bomb went off one hour after services had ended. No one was injured. “I got mixed on times and set it to go off at the wrong time. If I would have set it an hour earlier, I would have killed them all. And I was trying to kill them all.”

In his interview with the Post-Dispatch, Franklin admitted shooting Flynt outside a courthouse in Georgia in 1978, where the publisher was on trial for obscenity. Franklin said he did not like Hustler’s pictures of interracial couples. On May 29, 1980, Jordan was shot and seriously wounded outside the Marriott Inn in Fort Wayne, Ind. Asked about the Jordan shooting, Franklin would say only, “I did it.” He was finally caught that year while selling his blood in Florida. A nurse recognized a bald eagle tattoo on his arm from descriptions for a suspect being sought in several murders and called authorities. He was sentenced to death in Missouri in 1997.

Lankford said Franklin called him regularly to talk during his incarceration — even tracking him down by phone after Lankford’s retirement. “You’re dealing with a homicidal maniac, a person who at the time was all screwed up in the head,” Lankford said. “He was a racist and a Nazi. But he finally came to grips with himself and was sorry that he had done it.”

"Joseph Paul Franklin Timeline," by Brooke Adams. (Last Updated Nov 20 2013 07:29 am)

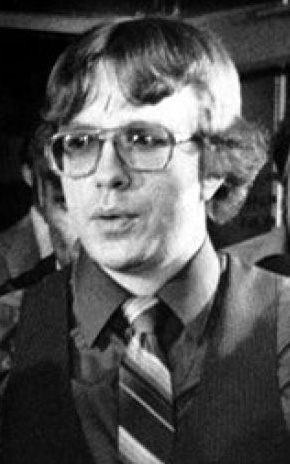

Avowed racist Joseph Paul Franklin, 31, served as his own attorney during his trial on first-degree murder charges in the sniper killing of two black joggers. This photo was taken during the trail on Sept. 3, 1981. The case was expected to go to the jury Friday afternoon.

Juy 8- Joseph Paul Franklin, avowed racist charged with shooting former National Urban League director Vernon Jordan, leaves U.S. District Court in Fort Wayne, Thursday. Franklin was told by a federal judge that he need not furnish samples of his handwriting to be compared with Fort Wayne motel registration cards allegedly signed around the time Jordan was shot. Franklin was wheel-chair bound because of knife wounds he suffered in Marion, Ill. federal prison. Atlanta attorney Vernon E. Jordan Jr. addresses a news conference in New York City on June 15, 1971. Jordan is named executive director of the National Urban League, the established African American organization. Urban League Director Vernon Jordan speaks at a National Urban Affairs Council luncheon in New York, Friday, May 30, 1981, one year after he was wounded in an unsolved shooting in Fort Wayne, Ind. Jordan warned that the United States is turning into a meaner, more selfish country, as the government abandons the black poor.

David Martin, gunned down in a racially motivated attack while jogging with white women in Liberty Park on Aug. 20, 1980. Martin was 18 years old. Ted Fields was 20 when Joseph Paul Franklin shot him and 18-year-old David Martin outside Salt Lake City's Liberty Park on Aug. 20, 1980. Hustler magazine founder Larry Flynt arrives at the premiere of the documentary 'Larry Flynt: The Right to be Left Alone' at The Paley Center for Media Friday, Oct. 26, 2007 in New York.

The state of Missouri plans to execute Joseph Paul Franklin by lethal injection at midnight on Nov. 20 for the murder of Gerald C. Gordon. Franklin shot Gordon on Oct. 8, 1977, as he stood outside the Brith Sholom Kneseth Israel Congregation synagogue in Richmond Heights, Mo. Franklin has been found guilty in seven additional murders. He has admitted or been linked to two bombings, at least 16 bank robberies and about a dozen other ambush-style attacks that left as many as eight people dead. April 13, 1950 • James Clayton Vaughn Jr. is born in Mobile, AL to James Clayton Vaughn Sr. and Helen Rau.

1976 • Vaughn changes his name to Joseph Paul Franklin, after Paul Joseph Goebbels and Benjamin Franklin.

July 25, 1977 • Franklin bombs the Rockland, Maryland, home of Morris Amitay, a Jewish lobbyist.

July 29, 1977 • Franklin bombs the Beth Sholom synagogue in Chattanooga, Tenn. He is convicted of the bombing on July 17, 1984, and sentenced to 31 years in prison.

Aug. 7, 1977 • Franklin fatally shoots African-American Alphonse Manning Jr., 23, and Toni Schwenn, 23, a white woman, in Madison, Wis., shortly after robbing a bank. In 1986, Franklin receives two life sentences for the murders.

Oct. 8, 1977 • Franklin fires at a crowd outside Brith Sholom Kneseth Israel Congregation synagogue in Richmond Heights, Mo., killing Gerald C. Gordon, 42, of Chesterfield, Mo., and wounding William Lee Ash, 30, of Akron, Ohio. He is convicted in 1997 and receives a death sentence.

Feb. 2, 1978 • Franklin kills African American Johnny Brookshire, 22, and wounds his white wife, Joy Williams, 23, in Atlanta, Ga.

March 6, 1978 • Larry Flynt, publisher of "Hustler" magazine, and his attorney Gene Reeves are shot while in Lawrenceville, Ga. Flynt is paralyzed from the waist down. Franklin later admits to the shooting.

July 29, 1978 • Franklin fatally shoots African American William Bryant Tatum and wounds his white girlfriend, Nancy Hilton, 18, in Chattanooga, Tenn. He confesses, pleads guilty and receives a life sentence in 1998.

July 12, 1979 • Franklin fatally shoots Harold McIver, 29, an African-American man and Taco Bell manager, in Doraville, Georgia.

Aug. 18, 1979 • Franklin fatally shoots Aftican American Raymond Taylor, 28, in Falls Church, Va.

Oct. 21, 1979 • Franklin fatally shoots Jesse E. Taylor, 42, an African-American, and Marion Bresette, 31, who was white, in Oklahoma City. He is charged with the crimes but the case is later dropped.

Dec. 5, 1979 • Franklin fatally shoots Mercedes Lynn Masters, 15, a white prostitute, after she tells him she had had African-American customers.

Jan. 12, 1980 • Franklin fatally shoots African American Lawrence E. Reese, 22, in Indianapolis.

Jan. 14, 1980 • Franklin fatally shoots African American Leo Thomas Watkins, 19, in Indianapolis.

May 2, 1980 • Franklin fatally shoots Rebecca Bergstrom, 20, a white woman, in Mill Bluff State Park, Wis. He admits the murder in 1984.

May 29, 1980 • Vernon E. Jordan Jr., president of the National Urban League, is shot outside a Marriott Inn in Fort Wayne, Ind. Franklin is later charged with attempted murder, but is acquitted after a trial in August 1982. Years later, Franklin admits shooting Jordan.

June 8, 1980 • Franklin fatally shoots cousins Darrell Lane, 14, and Dante Evans Brown, 13, both African American, in Cincinnati, Ohio. He is convicted in October 1998 and receives two life sentences.

June 15, 1980 • Franklin fatally shoots Arthur Smothers, 22, an African-American, and Kathleen Mikula, 16, a white, in Johnstown, Pa.

June 25, 1980 • Franklin fatally shoots Nancy Santomero, 19, and Vickie Durian, 26, in Pocahontas County, Va., after one of the white women said she had had a boyfriend who was African-American. He confesses to the murders in 1984.

Aug. 10, 1980 • Franklin arrives in Utah, staying in various local motels.

Aug. 20, 1980 • Ted Fields, David Martin, Terry Elrod and Karma Ingersoll are crossing 500 East at 900 South at 10:15 p.m. after jogging in Liberty Park as shots are fired. Fields, 20, and Martin, 18, both African-American, are killed.

Aug. 22, 1980 • Franklin leaves Utah and travels to Nevada and then San Francisco, Calif.

Sept. 25, 1980 • Franklin is arrested in Florence, Kentucky, on car theft charges but escapes from the jail five hours later, setting off a nationwide manhunt.

Oct. 28, 1980 • FBI agents arrest Franklin at Sera-Tec Biologicals, a blood bank, in Lakeland, Fla.

Oct. 31, 1980 • A federal jury in Utah indicts Franklin for violating the civil rights of Fields and Martin. His bail is set at $1 million. Other states begin linking him to sniper shootings.

Nov. 5, 1980 • First-degree murder charges for deaths of Fields and Martin are filed against Franklin in state court.

March 4, 1981 • After deliberating 14 hours, a federal jury in Utah finds Franklin guilty of civil rights violations for murdering Ted Fields and David Martin. The verdict followed a two-week trial.

March 18, 1981 • Franklin is charged with 1979 Oklahoma and 1980 Indiana murders.

March 23, 1981 • Franklin is sentenced to two consecutive life sentences in federal court for the Utah murders.

Sept. 18, 1981 • In a case brought by the state of Utah, Franklin is found guilty of first-degree murder. He subsequently receives two consecutive life sentences.

Feb. 3, 1982 • Franklin is stabbed 15 times by inmates three days after arriving at the federal prison in Marion, Ill.

Feb. 27, 1997 • Franklin receives a death sentence in Missourifor killing Gerald C. Gordon.

"Missouri executes serial killer after Supreme Court clears way," by Karen Brooks. (11-20-13)

(Reuters) - Missouri serial killer Joseph Paul Franklin was executed by lethal injection on Wednesday after the U.S. Supreme Court cleared the way for him to be put to death for murdering a man outside a synagogue in 1977, a corrections spokesman said. Franklin, an avowed white supremacist, was convicted and sentenced to death for killing Gerald Gordon, 42, and wounding two other men in a St. Louis-area synagogue parking lot. But he also was linked to the deaths of at least 18 other people. Franklin, 63, was pronounced dead at 6:17 a.m. CST (1217 GMT) at the Missouri Eastern Correctional Center in Bonne Terre, said Mike O'Connell, a spokesman for the Missouri Department of Public Safety.

The U.S. Supreme Court had cleared the way earlier on Wednesday for the execution to move forward, lifting two stays that would have allowed Franklin to challenge Missouri's new lethal drug protocol, and argue his claim that he was mentally incompetent and could not be executed. The stays were granted on Tuesday by two federal judges and immediately appealed by the state. Franklin was the 35th inmate executed in the United States in 2013 and the first in Missouri in nearly three years, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

He was convicted of killing eight people in the late 1970s and 1980s in racially motivated attacks around the country. The victims included two African-American men in Utah, two African-American teenagers in Ohio and an interracial couple in Wisconsin. He also had admitted to shooting Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt in 1978, paralyzing him. Flynt argued that Franklin should serve life in prison and not be executed.

FIRST EXECUTION UNDER NEW PROTOCOL

Franklin was the first inmate in Missouri put to death under the state's new execution protocol. In October, the state changed its protocols to allow for a compounded pentobarbital, a short-acting barbiturate, to be used in a lethal dose for executions. The state also said it would make the compounding pharmacy mixing the drug a member of its official "execution team," which could allow the pharmacy's identity to be kept secret.

Missouri is one of many U.S. states that have been seeking out drugs for executions from compounding pharmacies now that a growing number of pharmaceutical manufacturers refuse to allow their drugs to be used for the purpose. The practice is controversial because drugs mixed in compounding pharmacies are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Critics contend use of the compounded drugs could result in needless suffering and botched executions, but states including Missouri have pressed ahead. Franklin was one of nearly two dozen plaintiffs challenging the constitutionality of Missouri's new execution protocol.

In granting a stay on Tuesday, U.S. District Judge Nanette Laughrey had noted that Missouri issued three different protocols in the three months preceding Franklin's execution date and as recently as five days before. "Franklin has been afforded no time to research the risk of pain associated with the department's new protocol, the quality of the pentobarbital provided, and the record of the source of the pentobarbital," Laughrey wrote in the stay order entered in federal court in Jefferson City, Missouri.

"Missouri executes white supremacist serial killer," by Jim Salter. (Associated Press November 20, 2013)

BONNE TERRE, Mo. — Joseph Paul Franklin, a white supremacist who targeted blacks and Jews in a cross-country killing spree from 1977 to 1980, was put to death Wednesday in Missouri, the state's first execution in nearly three years.

Franklin, 63, was executed at the state prison in Bonne Terre for killing Gerald Gordon in a sniper shooting at a suburban St. Louis synagogue in 1977. He was convicted of seven other murders, but the Missouri case was the only one resulting in a death sentence. Franklin has also admitted to shooting and wounding civil rights leader Vernon Jordan and Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt, who has been paralyzed from the waist down since the attack in 1978.

Mike O'Connell, a spokesman for the Missouri Department of Corrections, said Franklin was pronounced dead at 6:17 a.m. The execution began more than six hours later than intended, and it took just 10 minutes. Franklin declined to make a final statement. Wearing black rimmed glasses with long hair tucked behind his ears, he swallowed hard as five grams of pentobarbital were administered. He breathed heavily a couple of times then simply stopped breathing. Guards closed the curtains to the viewing area while medical personnel confirmed Franklin was dead.

"The cowardly and calculated shootings outside a St. Louis-area synagogue were part of Joseph Paul Franklin's long record of murders and other acts of extreme violence across the country, fueled by religious and racial hate." Gov. Jay Nixon said in a statement read to reporters by George Lombardi, director of the Department of Corrections, after the execution.

Franklin's lawyer had launched three separate appeals: One claiming his life should be spared because he was mentally ill; one claiming faulty jury instruction when he was given the death penalty; and one raising concerns about Missouri's first-ever use of the single drug pentobarbital for the execution. But his fate was sealed early Wednesday when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a federal appeals court ruling that overturned two stays granted Tuesday evening by district court judges in Missouri. The rulings lifting the stay were issued without comment.

Franklin, a paranoid schizophrenic, was in his mid-20s when he began drifting across the country. He bombed a synagogue in Chattanooga, Tenn., in July 1977. No one was hurt, but soon, the killings began. He arrived in the St. Louis area in October 1977 and picked out the Brith Sholom Kneseth Israel synagogue from the Yellow Pages. He fired five shots at the parking lot in Richmond Heights after a bar mitzvah on Oct. 8, 1977. One struck and killed Gerald Gordon, a 42-year-old father of three. Franklin got away. His killing spree continued another three years.

Several of his victims were interracial couples. He also shot and killed, among others, two black children in Cincinnati, three female hitchhikers and a white 15-year-old prostitute, with whom he was angry because the girl had sex with black men. He finally stumbled after killing two young black men in Salt Lake City in August 1980. He was arrested a month later in Kentucky, briefly escaped, and was captured for good a month after that in Florida. Franklin was convicted of eight murders: two in Madison, Wis., two in Cincinnati, two in Salt Lake City, one in Chattanooga, Tenn., and the one in St. Louis County. Years later, in federal prison, Franklin admitted to several crimes, including the St. Louis County killing. He was sentenced to death in 1997.

In an interview with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch on Monday, Franklin insisted he no longer hates blacks or Jews. While he was held at St. Louis County Jail, he said he interacted with blacks at the jail, "and I saw they were people just like us." He has made similar statements to other media but has denied repeated interview requests from The Associated Press. Franklin's attorney Jennifer Herndon said his reasoning exemplified his mental illness: He told her the digits of the AP's St. Louis office phone number added up to what he called an "unlucky number," so he refused to call it.

Victims:

Alphonse Manning,23

Toni Schwenn, 23

Gerald Gordon, 42

Johnnie Brookshire, 22

William Bryant Tatum

Harold McIver, 29

Raymond Taylor

Jesse Taylor, 42

Marian Vera Bresette, 31

Mercedes Lynn Masters, 15

Lawrence Reese, 22

Leo Thomas Watkins, 19

Rebecca Bergstrom, 21

Darrell Layne, 14

Dante Evans Brown, 13

Arthur Smothers, 22

Kathleen Mikula, 16

Nancy Santomero, 19

Vicki Durian, 26

Ted Fields, 20

David Martin, 18

In September of 1977, believing that Jews were “enemies of the white race,” Joseph Paul Franklin, born as James Clayton Vaughn, Jr., drove to Dallas, Texas after robbing a bank in Little Rock, Arkansas. In Dallas, Franklin bought a 30-06 rifle with a telescopic sight. He then drove to St. Louis, Missouri, checked into a hotel under an assumed name, scouted the city for synagogues, and finally chose Brith Sholom Kneseth Israel Congregation in Richmond Heights. Franklin had previously bombed a synagogue and another building and had long considered developing a plan to murder numerous Jews as they left synagogue, as he believed that African-Americans and Jews were “enemies of the white race.”

To prepare for the crime, Franklin bought some ten-inch nails, a guitar case, and a bicycle. He tested the bicycle to assure himself that it could be used to enable him to leave the scene of the crime. He drove the nails into a telephone pole to serve as a rifle rest. Later, he ground the serial number off of the rifle. He then cleaned the rifle, ammunition, and guitar case of any fingerprints and, thereafter, he used gloves to handle the equipment. Lastly, he put the rifle into the guitar case and hid them both in some bushes near the synagogue.

On Saturday, October 8, 1977, Franklin waited outside the synagogue for people to emerge. Shortly before 1:00 p.m., some of the guests left the synagogue and walked toward their cars. Franklin began firing on the guests. He fired five shots from approximately one hundred yards. Gerald Gordon was shot in the left side of his chest and later died from blood loss resulting from damage to his lung, stomach, spleen, and other internal organs. Steven Goldman was grazed on the shoulder. William Ash was wounded in the left hand and later lost his small finger on that hand.

Having fired all his ammunition, Franklin abandoned the rifle and the guitar case. He then rode his bicycle to a nearby parking lot where his automobile was parked, hid the bicycle in some bushes, and left St. Louis by car. Police recovered a Remington .30-06 rifle, spent shell casings, a guitar case, and a bicycle used in connection with the shootings, but never apprehended the sniper.

The crimes remained unsolved for seventeen years. In 1994, while serving six consecutive life sentences at a federal penitentiary in Marion, Illinois, Franklin requested an interview with an agent from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). During the interview, Franklin confessed to the 1977 St. Louis synagogue shootings. Franklin gave the FBI agent a detailed account of his preparation for and execution of the shootings, which included: (1) buying a .30-06 rifle in Texas, obliterating the rifle’s serial numbers, and wiping his fingerprints from the rifle and shell casings; (2) initially choosing Oklahoma City as the location for the shootings, but selecting St. Louis instead, believing St. Louis had a larger Jewish population; (3) choosing the Richmond Heights (St. Louis) synagogue because it had bushes for cover; (4) carrying the rifle in a guitar case to the scene the night before the shootings; (5) hammering nails into a telephone post to use as a rifle prop; (6) using a bicycle to flee the scene undetected after the shootings; and (7) monitoring the police radio to determine whether the police were looking for him. Franklin repeated his confession in a videotaped interview to a Richmond Heights police officer, and told the officer he wished he “had killed five Jews with the five bullets.”

UPDATE: After initially receiving a stay that delayed his execution for several hours, Joseph Franklin was executed despite claims that using pentobarbital for the execution might cause him undue pain.

James Clayton Vaughn Jr. AKA Joseph Paul Franklin

Information researched and summarized by Sam Brauer, Ryan A. Bruch, Ashleigh Benois

Department of Psychology, Radford University, Radford, VA 24142-6946

Date - Age - Life Event

04/13/1950 0 Born in Mobile, Alabama as James Clayton Vaughn, Jr.

1957 7 Head Injury - Bicycle Accident

1958 8 Father abandons family. Would return on occasion.

1965 15 Stole copy of Mein Kampf

1967 17 Dropped out of Murphy High School at the end of his junior year.

02/1968 18 Met Bobbie Louise Dorman (16) and marries her two weeks later. They divorce after 4 mo.

1968 18 Joined Arlington American Nazi Party

1969 19 Becomes obsessed with Charles Manson’s plan for a race war

1970 20 Begins insulting mixed-raced couples

1972 22 Conviction for carrying a concealed weapon in Fairfax, VA

1973 23 Joins National States Rights Party

1973 23 Begins selling racist newspaper, The Thunderbolt

1976 26 Joined KKK in Atlanta, GA (quit after a few months due to Klan’s lack of violence)

9/6/1976 26 Tailed a Black man with a white date, cornered them, and sprayed them with mace (Md.)

1976 26 Sent threating letter to newly elected President Jimmy Carter

1976 26 Changed name to Joseph Paul Franklin

1977 27 Joined Alabama National Guard

1977 27 Commits first major bank robbery in Atlanta, GA

07/25/1977 27 Bombs home of Jewish leader, Morris Amitay

07/29/1977 27 Bombs of synagogue in Chattanooga, TN

08/07/1977 27 Goes to Madison, WI, robs a bank, plans to shoot Archie Simonson but instead shoots an

interracial couple, Alphonse Manning (23) and Toni Schwenn (23).

1977 27 Robs a bank in Little Rock, AR

1977 27 Drives to Dallas, TX buys a Remington 30.06

08/02/1977 27 Robs a bank in Columbus, Ohio

10/08/1977 27 Kills Gerald Gordon (42) and wounds William Ash (30) in St. Louis, MO (Remington 700)

02/1978 28 Kills Johnny Brookshire (22) and wounds (paralyzed) his white girlfriend, Joy Williams

(23), in Atlanta, GA

03/06/1978 28 Wounds/paralyzes Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt in Lawrenceville, GA (.44)

03/06/1978 28 Wounds Gene Reeves (latter recovers) (.44)

1978 28 Robs a bank in Louisville, KY

1978 28 Robs a bank in Atlanta, GA

07/29/1978 28 Shoots an interracial couple at Pizza Hut – kills Bryant Tatum, and wounds girlfriend,

Nancy Diane Hilton(18)

1978 28 Robs a bank in Montgomery, AL

1978 28 Returns to Alabama and meets Anita Carden (16) in an ice cream shop, they begin dating

1979 29 Franklin and Anita get married in DeKalb County Courthouse (Atlanta, GA)

07/12/1979 29 Shoots and kills Harold McIver (29) at Taco Bell in Doraville, GA (30.30)

08/18/1979 29 Kills Raymond Taylor at Burger King in Falls Church, VA (30.30)

08/25/1979 29 First offspring – Montgomery, AL

10/21/1979 29 Shoots and kills a mixed-race couple Jesse Taylor (42) and Marian Vera Bressette (31) in Oklahoma City, OK

12/05/1979 29 Cheats on his wife and kills prostitute Mercedes Masters (15) after admission of

interracial relations

01/08/1980 30 Kills Black man, Lawrence Reese (22), at fried chicken fast food restaurant

01/14/1980 30 Kills Leo Thomas Watkins (19) through plate glass of convenience store in Indianapolis

shopping mall (30.30)

April 1980 30 Franklin and his wife Anita separate.

05/02/1980 30 Kills hitchhiking student Rebecca Bergstorm in Mill Bluff State Park, WI

05/29/1980 30 Shoots civil rights leader. Vernon Jordan. in Fort Wayne, IN

06/08/1980 30 Kills cousins Darrell Layne (14) and Dante Evans Brown (13) in Cincinnati, OH

06/15/1980 30 Kills Arthur Smothers (22) and Kathleen Mikula (16) in Johnstown, PA

06/24/1980 30 Robs a bank in Burlington, NC

06/25/1980 30 Kills hitchhikers Nancy Santomero (19) and Vicki Durian (26) in Pocahontas, WV (.44

Ruger)

08/20/1980 30 Kills Ted Fields (20) and David Martin (18) in Salt Lake City, UT (Marlin lever action)

09/24/1980 30 Franklin is arrested in Florence, Kentucky and then escapes from the police department/

10/28/1980 30 Franklin is recaptured in Lakeland, FL

11/07/1980 30 Extradited to Salt Lake City, UT and arraigned for murders of Ted Fields and David

Martin.

03/04/1981 31 Federal Trial – convicted of violating the civil rights of Fields and Martin and sentenced to two consecutive life sentences

06/02/1981 31 State Trial – convicted of killing Fields and Martin, sentenced to two more life sentences due to hung jury regarding death penalty (attempted escape but recaptured) sent to

Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield MI

01/31/1982 32 Transferred to United States Penitentiary in Marion, IL to begin serving life sentences

02/03/1982 32 Stabbed 15 times in the neck and abdomen by a group of African Americans

08/17/1982 32 Federal Trial – found not guilty for violating the civil rights of Vernon Jordan

1983 33 Partially confesses to the Larry Flynt shooting

1983 33 Confesses to shooting of Larry Flynt and bombing Morris Amitay’s house in Washington DC

03/01/1984 34 Confesses to the murder of Rebecca Bergstrom; the murders of Santomero and Durian;

Chattanooga synagogue bombing (tried in July and sentenced to 15-20yrs for bombing & 6-10yrs for possession of explosives), Rainbow murders, shooting Alphonse Manning (23) and Toni Schwenn (23)

02/14/1986 36 Convicted in Wisconsin of killing Manning and Schwenn. Sentenced to two consecutive

life sentences

08/19/1990 40 Admits to Killing Ted Fields and David Martin in Salt Lake City, UT

06/04/1993 43 Jacob Beard is found guilty of two counts of 1st-Degree murder for the Rainbow murders

of Satomero and Durian although Franklin confessed to the murders

1994 44 Franklin confesses to killing Gerald Gordon

1995 45 Admits to shooting Vernon Jordan

11/18/1996 46 Tells Deborah Dixon, WKRC Cincinnati reporter, that he killed Santomero and Durian

because “They dated black people”

02/27/1997 47 Found guilty of killing Gerald Gordon and sentenced to death

03/10/1997 47 Admits to killing Raymond Taylor

04/13/1997 Admits to murdering Arthur Smothers and Kathleen Mikula. Later confesses to

murdering Darrell Lane and Dante Evans Brown

10/22/1997 47 Found guilty of murdering Darrell Lane and Dante Evans Brown, sentenced to 40 years

to life in prison.

1998 48 Admits to killing William Tatum, pleads and receives two concurrent life sentences (one

for murder and one for robbery)

03/1998 48 Confesses to killing prostitute Mercedes Masters and Harold McIver

11/01/1999 49 Confesses to killing Johnny Brookshire in 1978

2000 50 Jacob Beard is retried for the Rainbow murders and found not guilty

2004 54 US District Court requires release or retrial of Franklin for the Gerald Gordon murder

2006 56 Federal Judge puts the Missouri death penalty on hold over concerns involving lethal rugs.

July 2007 57 Federal Appellate Court overturns U.S. District Court decision

2008 58 U.S. Supreme Court decides that the current method of execution (lethal injection) is

constitutionally permissible

2010 60 US Supreme court refuses to hear Missouri lethal injection case Clemons v. Crawford,

lethal injection stands as permissible and Missouri attorney general states executions will begin again.

General Information

Sex Male

Race White

Number of victims 7-20+

Country where killing occurred United States

States where killing occurred Wisconsin, Missouri, Tennessee, Georgia, Virginia, Indiana,

Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Utah, Oklahoma

Cities where killing occurred

Type of killer Organized Visionary

Height 5’11”

Childhood Information

Date of birth April 13, 1950

Location Mobile, Alabama

Birth order 2nd of 4

Number of siblings 4

XYY? No

Raised by Mom

Birth category Middle

Parent’s marital status Divorced

Did serial killer spend time in an orphanage? No

Did serial killer spend time in a foster home? No

Was serial killer ever raised by a relative? No

Did serial killer ever live with adopted family? No

Did serial killer live with a step-parent? No

Family event Parents divorce in 1950s

Age of family event Younger than 10 years old

Problems in school? No

Teased while in school? No

Physically attractive? No

Physical defect? Yes

Speech defect? No

Head injury? Bike accident, age 7

Physically abused? Yes, by both parents

Psychologically abused? Yes

Sexually abused? No

Father’s occupation

Age when first had intercourse

Mother’s occupation

Father abused drugs/alcohol Yes; alcohol

Mother abused drugs/alcohol

Cognitive Ability

Highest grade in school 10th

Highest degree None

Grades in school Average

IQ Above average

Source of IQ information Ayton (2011, pg. 272)

Work History

Served in the military? Yes

Branch Alabama National Guard

Type of discharge Unknown

Saw combat duty No

Killed enemy during service? No

Applied for job as a cop? No

Worked in law enforcement? No

Fired from jobs? No

Types of jobs worked Unknown

Employment status during series Unknown

Relationships

Sexual preference Heterosexual

Marital status Married

Number of children 1

Lives with his children No

Living with Mother

Triad

Animal torture No

Fire setting No

Bed wetting No

Killer Psychological Information

Abused drugs? No

Abused alcohol? No

Been to a psychologist (prior to killing)? No

Time in forensic hospital (prior to killing)? None

Diagnosis n/a

Killer Criminal History (Prior to the series)

Committed previous crimes? Bank robbery, Fire-bombed home of Morris Amitay, firebombed

synagogue, and Threw mace at mixed-race couple

Spent time in jail? No

Spent time in prison? No

Killed prior to series? Age? No; n/a

Serial Killing

Number of victims (suspected of) 21 murders

Number of victims (confessed to) 17 murders

Number of victims (convicted of) 8 murders

Victim type Mixed-race couples, and anyone who ever mixed race

Killer age at start of series 27yrs

Killer age at end of series 30yrs

Date of first kill in series August 7, 1977

Date of final kill in series August 20, 1980

Gender of victims Male (14) and Female (7)

Race of victims White (8) and African American (13)

Age of victims 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19(2), 20, 22(3), 23(2), 26, 29, 31, 42(2)

Type of victim Mixed-race couples

Method of killing Shooting

Weapon Guns

Was gun used? Yes

Type Rifles, Shotguns, and Handguns

Did killer have a partner? No

Name of partner n/a

Sex of partner n/a

Relationship of partner n/a

Type of serial killer Organized missionary

How close did killer live? Drifter

Location of first contact Unknown

Location of killing Madison, Wisconsin

Killing occurred in home of victim? No

Killing occurred in home of killer? No

Victim abducted or killed at contact? Killed at contact, if contact was made

Behavior During Crimes

Rape? No

Tortured victims? No

Stalked victims? Sometimes

Overkill? No

Quick & efficient? Yes

Used blindfold? No

Bound the victims? No

After Death Behavior

Sex with the body? No

Mutilated body? No

Ate part of the body? No

Drank victim’s blood? No

Posed the body? No

Took totem – body part No

Took totem – personal item No

Robbed victim or location No

Disposal of Body

Left at scene, no attempt to hide Yes

Left at scene, hidden No

Left at scene, buried No

Moved, no attempt to hide No

Moved, hidden No

Moved, buried No

Cut-op and disposed of No

Burned body No

Dumped body in lake, river, etc. No

Moved, took home No

Sentencing

Date killer arrested September 24, 1980

Date convicted About 1981

Sentence Death sentence and multiple life sentences

Killer executed? Not yet

Did killer plead NGRI? No

Was the NGRI plea successful?

Did serial killer confess? Yes

Name and state of prison Potosi Correctional Center near Mineral Point, Missouri

Killer committed suicide? No

Killer killed in prison? No

"Three decades later, the effects of synagogue shooting are still being felt, In Race, Frankly," by Ellen Futterman, Editor of Jewish Light. (Tue May 25, 2010 7:00 pm)

It was supposed to be one of the most memorable days of his young life. And in fact Richard "Ricky" Kalina's bar mitzvah certainly was that, but not in the way he, or his parents, or any of the guests had envisioned. On the day that in the Jewish religion signifies Ricky's passage from boyhood to manhood, the 13-year-old was forced to deal with a tragedy of life-changing proportion. It left one family friend dead, two others wounded and a neo-Nazi serial killer on the loose. "It was the day that I lost my innocence," says Kalina, now 45, married and the father of two. "My whole life changed in a matter of seconds."

The day Rick kalina became a man - Proud parents Maxine and Merwyn Kalina had invited about 200 guests to their eldest son Ricky's bar mitzvah at Brith Sholom Kneseth Israel in Richmond Heights on Oct. 8, 1977. A reception at Le Chateau in Frontenac was planned for the evening and a brunch at the Kalina's home in Town & Country would take place the next day. A separate kids' party was to occur later that Sunday. "I felt good about the bar mitzvah service," says Rick Kalina, recently recalling the sunny autumn day more than 32 years ago. "I read my Haftorah without messing up, recited the prayers and gave my speech. It all went very well."

Steve Goldman had been standing on the synagogue parking lot talking to Gordon, who had one of his three young daughters in tow. Gordon's wife and other daughters were nearby. Goldman heard a popping noise then felt what he thought was some sort of bug bite his shoulder. Like Ricky, Goldman thought Gordon was joking when he grabbed himself. But then he was lying on the pavement, bleeding from his chest. Goldman swooped up Gordon's little girl and held her tight as they ducked between parked cars to avoid more bullets. "She was yelling for her daddy," Goldman, now 62, remembers.

Ricky ran inside to find his parents. He told them Gerry Gordon had been shot. The Gordons, who had recently moved to Chesterfield from Creve Coeur, were among the Kalinas' closest friends.

Kalina talks about the shooting - "There was such disbelief and horror," Rick Kalina recalls. "This was long before cell phones. I remember running to the office of the temple, but it was locked. We needed to find someone to unlock it so we could call an ambulance. I remember people trying to get out of the synagogue as fast as they could."

Ambulances arrived quickly and rushed Gordon, 42, to the old St. Louis County Hospital where he died in an operating room about two hours after he was shot. A bullet had pierced his left arm and lodged in his chest, destroying his internal organs.

Another guest, William Lee Ash, 30, of Akron, Ohio, lost his left pinkie finger, which got embedded in his hip when he was struck. He was treated and released from County Hospital.

In all, five shots were fired in fast succession. One of the bullets passed through Goldman's suit coat, though he was not injured. "I hadn't even realized that I had been hit until a police officer noticed a hole in my jacket," says Goldman.

Franklin's day in court - In 1997, roughly 20 years after the murder at his bar mitzvah, Rick Kalina found himself inside a St. Louis County courtroom listening to Joseph Paul Franklin tell how he wanted to kill as many Jews as possible and how he had traveled from state to state to do so.

Kalina listened as prosecutors told how Franklin had chosen BSKI randomly from the Yellow Pages and decided on it after visiting some other synagogues in the St. Louis area. He figured the high grass behind a telephone pole in view of BSKI's parking lot was a good place for him to stage an ambush.

Before the shooting, he purchased some 10-inch nails, a bicycle and a guitar case, which he used to carry a Remington 700 hunting rifle to his hiding location. He made sure to scratch the serial number from his gun so police couldn't trace it.

When he arrived that Saturday morning, he hammered the nails into the pole to use as makeshift gun rests. He waited several hours for people to leave the synagogue before opening fire.

At roughly 1 p.m., after squeezing off five shots, he made his getaway on bicycle to a nearby location where he had parked his car. Then he drove south, never to be caught until he eventually confessed to the crime 17 years later.

"When they would bring (Franklin) into the courtroom, it was like the atmosphere turned ice cold," recalls Kalina, who attended the three-day murder trial alone, without friends or relatives by his side. "It was as if he had sucked all the life out of the room. He has the type of charisma that is just dead. It reeks of death."

In 1994, Franklin was incarcerated at the Marion, Ill., federal penitentiary where he first told the FBI, and later Richmond Heights police, that he was the one who had murdered Gerald Gordon at BSKI. He said a dream told him to confess and he always listens to his dreams.

At the time, he was serving six consecutive life sentences -- two federal and four state -- for four murders: the killing of an interracial couple in Wisconsin in 1977 and the killing of two black men in Salt Lake City in 1980 as they jogged with white women. He was involved in roughly 20 violent crimes, including the 1978 shooting of Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt, which left Flynt paralyzed, as well as the shooting of then-Urban League President Vernon Jordan, though Franklin was acquitted in 1982.

It took the jury 39 minutes to convict Franklin of the sniper killing of Gerald Gordon and 65 minutes the next day to agree that Franklin should die of lethal injection.

Franklin, who was quoted in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch after the trial, claimed after the trial that his only regret was that "killing Jews is not legal."

Aftermath of the shootings - Rick Kalina remembers feeling tremendously guilty and afraid in the aftermath of his bar mitzvah. "I felt a lot of kids pulled back from me. Friends I had (before the shootings) no longer wanted to be my friend," he says. "The anti-Semitism really came to the surface. Our house was vandalized with anti-Semitic slurs. I remember being called a kike. Within a year of the incident, we moved from our house in Crystal Lake to Spoede."

Kalina points out that 30 years ago therapy was something many people, including his parents, shied away from because of how others would perceive it. There were no grief counselors to help him at school. His parents, wanting to protect their son, didn't allow him to attend Gerry Gordon's funeral. Essentially, he was on his own to figure out how to deal with the tragedy.

"The world wasn't really equipped to deal with this kind of hate crime," he says. "The entire Jewish community in St. Louis at that point in time hid from this. (The Jewish) Federation didn't take a position or a stand. Today, the organization would set up a scholarship for the children of the victim or raise money to support the family. There would be counseling and help. But it was a different time back then."

Eventually, when he was in his mid-20s, Kalina did go to therapy, in part to help deal with the bar mitzvah incident. "I have issues associated with post-traumatic stress syndrome," he explains. "There are certain times when I feel cornered and threatened and my reactions are not the typical reactions."

Kalina, who now belongs to Shaare Zedek Synagogue, says he has a hard time picking up his older daughter from Sunday school. Last year he went to BSKI to attend a bar mitzvah -- the first one he had been to there since his own -- and found himself running to his car when it was over. "I didn't park in the (temple) parking lot," he says. "I parked in the street. There are still really crazy things (I do). And yet I don't want my kids to be affected by my fears and experiences."

Kalina says that until now he has declined to be interviewed about the BSKI shootings because "one of my fears is publicity and the other is that sometimes you don't always get what you're hoping for. It's safer to say 'no comment.'" But he is speaking out, in part because he feels too many people in the Jewish community still "act naively" when it comes to hate violence.

"There is still denial in the Jewish community about this," he says. "That in 2009 we had a Nazi organization hold a rally under the Arch and we didn't demand to know who these people are. That's crazy. They could be our teachers, our neighbors, our co-workers. Freedom of speech is one thing, but that stops when it hurts me and the people I love."

Sheila Gordon, the widow of Gerry Gordon, declined to be interviewed for this article because, she says, it is still too painful for her to speak publicly about her husband's murder. Her three daughters, now married with children and each still living in the St. Louis area, also declined to be interviewed.

Joseph Paul Franklin today - One person who is very eager to talk is Joseph Paul Franklin. Currently serving his death sentence at the Potosi Correctional Center in Mineral Point, Mo., about 90 miles southeast of St. Louis, Franklin spends days and nights alone in a cell waiting to be executed. According to the Missouri Department of Corrections, he remains in "administrative/disciplinary segregation for poor institutional behavior" and is no longer allowed in-person interviews with the media. I went to the prison earlier this year and spoke to Franklin by phone.

Now 60 years old, Franklin is eager to discuss everything from his interest in Eastern religions to how meditation turned his life around to what he says was an abusive childhood to a desire for female companionship. When it comes to reflecting on his deadly, four-year crime spree in the late 1970s and the repercussions of hate violence, he says only: "The devil had control over my mind at the time. I was out of my mind for real. It's been, like, 30-something years ago. I've changed a lot. I wish it never happened, but there is no way you can go back and undo something like that."

Franklin, who represented himself during the BSKI trial, waived his right to an appeal and requested an execution date after he was sentenced for the sniper killing of Gerald Gordon. Franklin had urged the jury to put him to death, saying he would kill again if he were released.

Some time later though, he filed an appeal, which eventually made its way to the Missouri Supreme Court and was denied in June 2000. Franklin says he had changed his mind about being executed because "that's not what the Lord wanted me to do. I get signs from God about what to do. Also, I'm into numerology and get guidance from the numbers." He told me that prior to our conversation, he had checked my numbers using my name and phone number, and they turned out to be good.

Franklin says he "got into white supremacy" when he was around 18 and "became obsessed with anti-Jewish literature." He even changed his name when he was 25 from James Clayton Vaughn Jr. to Joseph Paul Franklin as a tribute to Nazism; Joseph Paul came from Joseph Paul Goebbels, Hitler's minister of propaganda.

Franklin grew up in Mobile, Ala., with two sisters and two brothers. He says his father was an alcoholic and his mother was abusive. "My brother and I would sleep together in the same bed when we were little. My mother would think of something we had done wrong during the day and get up in the middle of the night to beat us," he says, adding that he thinks the abuse he endured, coupled with his alcoholism, led him to become violent.

He says he no longer hates Jews or blacks, adding, "in fact, just the opposite." Meditation as well as learning about Hinduism, Buddhism and even Judaism, he says, has made him tolerant.

In late January, Missouri Attorney General Chris Koster asked the state Supreme Court to set an execution date for Franklin after a federal appeals court cleared the way for Missouri to resume scheduling executions by rejecting a lawsuit from eight inmates over the training and competence of the state's execution team. As of last week, no execution date for Franklin had been set.

Is he fearful about being executed?

"No, not really," he says. "I just figure may the will of God be done."

About.Com - Serial Killers: Paul Franklin

"Profile of Serial Killer Joseph Paul Franklin, Serial Extremist Killer," by Charles Montaldo.

Joseph Paul Franklin is a serial extremist killer whose crimes were motivated by a pathological hatred of African Americans and Jews. Fueled by the words of his hero, Adolf Hitler, Franklin went on a killing rampage targeting interracial couples and setting off bombs in synagogues.

His killing rampage lasted between 1977 and 1980, ending after his arrest in September 1980.

Childhood Years

Franklin (named James Clayton Vaughan Jr. at birth) was born in Mobile, Alabama on April 13, 1950 and was the second of four children in a volatile impoverished home. As a child Franklin, who felt different from other children, turned to reading books, mostly fairy tales, as an escape from the domestic violence in the home. His sister has described the home as abusive, saying Franklin was the target of much of the abuse.

Teen Years

During his teen years he was introduced to the American Nazi Party through pamphlets and he adopted the belief that the world needed to be "cleansed" of what he considered inferior races - mainly African Americans and Jews. He was in full agreement with the Nazi teachings and he became a member of the American Nazi Party, the Ku Klux Klan, and the National States Rights Party.

Name Change

In 1976, he wanted to join the Rhodesian Army, but because of his criminal background he needed to change his name to be accepted. He changed his name to Joseph Paul Franklin - Joseph Paul after Adolph Hitler's minister of propaganda, Joseph Paul Goebbels, and Franklin after Benjamin Franklin.

Franklin never did join the army, but instead launched his own war of the races.

Obsessed With Hate

Obsessed with hatred for interracial marriages, many of his killings were against black and white couples he encountered.

He has also admitted to blowing up synagogues and takes responsibility for the 1978 shooting of Hustler Magazine publisher, Larry Flynt and the 1980 shooting on civil rights activist and Urban League president Vernon Jordan, Jr.

Over the years Franklin has been linked to or confessed to numerous bank robberies, bombings and murders. However not all of his confessions are viewed as truthful and many of the crimes were never brought to trial.

Convictions

•Alphonse Manning and Toni Schwenn - Madison Wisconsin

•Bryant Tatum and Nancy Hilton - Chattanooga, Tennessee

•Donte Brown and Darrel Lane - Cincinnati, Ohio

•Ted Fields and David Martin - Salt Lake City, Utah

•Gerald Gordon - Potosi, Missouri

Eight life sentences and a death sentence has done little to change Franklin's radical racist views. He has told authorities that his only regret is that killing Jews isn't legal.

During a 1995 article published by Deseret News, Franklin seemed to boast about his killing sprees and the only regret that he seems to have is that there were victims that managed to survive his murderous rage. Franklin is currently on death row at the Potosi Correctional Center near Mineral Point, Missouri.

Update:

Franklin is scheduled to be executed Nov. 20. 2013 in Missouri. Much has changed since Franklin's 1995 interview. Pointing to his manic depression and mental illness as the driving force behind his fanatical hatred, he now says he regrets his crimes.

As for his upcoming execution, Franklin told The Hollywood Reporter, "I firmly believe that a government that forbids killing among its citizens should not be in the business of killing people itself."

Apparently, one of his victims agrees- Flynt has spoken out against Franklin's execution.

Missourians to Abolish the Death Penalty

Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty

Wikipedia: Joseph Paul Franklin

Joseph Paul Franklin

Born: James Clayton Vaughn, Jr., April 13, 1950, Mobile, Alabama

Joseph Paul Franklin (April 13, 1950 – November 20, 2013) was an American serial killer. He was convicted of several murders, and given six life sentences, as well as a death sentence. He confessed to the attempted murders of two prominent men: the magazine publisher Larry Flynt in 1978 and Vernon Jordan, Jr., the civil rights activist, in 1980. Both survived their injuries, but Flynt was left permanently paralyzed from the waist down. Franklin was not convicted in either of those cases.

Because Franklin has repeatedly changed his accounts of some cases, officials cannot determine the full extent of his crimes. His claims of racial motivation have been offset by a defense expert witness who testified in 1997 that Franklin was a paranoid schizophrenic who was not fit to stand trial.

Franklin was on death row for 15 years awaiting execution in the state of Missouri for the 1977 murder of Gerald Gordon.[1][2] He was executed by lethal injection on November 20, 2013.[3]

Early life

Franklin was born James Clayton Vaughn in Mobile, Alabama, to a poor family.[4] He suffered severe physical abuse as a child.[5] As early as high school, he had become interested first in evangelical Christianity, then Nazism, and later held memberships in both the National Socialist White People's Party and the Ku Klux Klan.[6] In the 1960s, Franklin was inspired to try to start a race war after reading Adolf Hitler's political manifesto Mein Kampf. "I've never felt that way about any other book that I read," he would reflect later. "It was something weird about that book."[7]

Crimes

For much of his life, Franklin was a drifter, roaming up and down the East Coast looking for chances to "cleanse the world" of people he considered inferior, especially blacks and Jews.[5]

1977

July 25, 1977. At 3:17 AM, a trunk load of dynamite is detonated outside the home of Jewish pro-Israel lobbyist Morris Amitay and his family. While the home was severely damaged, all occupants escaped except for their 6 month old beagle. Franklin confessed to the crime years later while in prison. "The Many Trials of a Killer," The Mobile Register October 18, 1988

July 29, 1977: Beth Sholom synagogue in Chattanooga is firebombed. Franklin has confessed to the crime.[5]

October 8, 1977: Franklin hid in long grass behind a telegraph pole at Brith Shalom, a synagogue in Richmond Heights, Missouri, and fired into a group of worshipers with a hunting rifle, killing Gerald Gordon and injuring two others. He confessed to this murder in 1995 and two years later was tried, convicted and sentenced to die.[5]

1978

Franklin claimed that, on March 6, 1978, he used a .44 caliber rifle to ambush Hustler publisher Larry Flynt and his lawyer Gene Reeves in Lawrenceville, Georgia. In his confession, Franklin said this was in retaliation for an edition of Hustler displaying interracial sex.[5]

July 29, 1978: Franklin hid near a Pizza Hut in Chattanooga, and shot and killed Bryant Tatum, a black man, with a 12-gauge shotgun; he also shot Tatum's white girlfriend, Nancy Hilton, who survived. Franklin confessed and pleaded guilty, being given a life sentence, as well as a sentence for an unrelated armed robbery in 1977.[5]

1979

July 12, 1979: Taco Bell manager Harold McIver (27), a black man, was fatally shot through a window from 150 yards (140 m) in Doraville, Georgia. Franklin confessed but was not tried or sentenced for this crime. Franklin said that McIver was in close contact with white women, so he murdered him.[5]

1980

May 29, 1980: Franklin said he shot and seriously wounded civil rights activist and Urban League president Vernon Jordan, Jr. after seeing him with a white woman in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Franklin initially denied any part in the crime and was acquitted, but later confessed.[5]

June 8, 1980: Franklin confessed to killing cousins Darrell Lane (14) and Dante Evans Brown (13) in Cincinnati, Ohio. Waiting on an overpass to shoot a racially mixed couple, he shot the boys instead. He was convicted in 1998 and received two life sentences for these murders.[8][9]

June 25, 1980: Franklin used a .44 Ruger pistol to kill two hitchhikers, Nancy Santomero (19) and Vicki Durian (26), in Pocahontas County, West Virginia. He confessed to the crime in 1997 to an Ohio assistant prosecutor in the course of investigation in another case; he said he picked up the white girls and decided to kill them after one said she had a black boyfriend. Jacob Beard of Florida, was convicted and imprisoned in 1993 on these charges. He was freed in 1999 and a new trial was ordered based on Franklin's confession.[8]

August 20, 1980: Franklin killed two black men, Ted Fields and David Martin, near Liberty Park located in Salt Lake City, Utah.[5] He was tried on federal civil rights charges as well as state first-degree murder charges.[10]

Conviction and imprisonment

Franklin tried to escape during the judgment of the 1997 Missouri trial on charges of murdering Gerald Gordon. He was convicted of the murder charge. The psychiatrist Dorothy Otnow Lewis, who had interviewed him at length, testified for the defense that she believed that he was a paranoid schizophrenic and unfit to stand trial. She noted his delusional thinking and a childhood history of severe abuse.[5]

In October 2013, Flynt called for clemency for Franklin asserting "that a government that forbids killing among its citizens should not be in the business of killing people itself."[11]

Franklin was held on death row at the Potosi Correctional Center near Mineral Point, Missouri. In August 2013 the Missouri State Supreme Court announced that Franklin would be executed later that year on November 20.[12] Missouri Attorney General Chris Koster said in a statement that by setting execution dates, the state high court "has taken an important step to see that justice is finally done for the victims and their families".[13]

Execution

Franklin's execution was complicated as it took place during a period when various European drug manufacturers refused or objected on moral grounds to having their drugs used in a lethal injection.[14] In response Missouri announced that it would use for Franklin's execution a new method of lethal injection, which used a single drug provided by an unnamed compounding pharmacy.[15]

A day before his execution, U.S. District Judge Nanette Laughrey (Jefferson City) granted a stay of execution over concerns raised about the new method of execution.[16] A second stay was granted that evening by U.S. District Judge Carol E. Jackson (St. Louis), based on Franklin’s claim that he is mentally incompetent to be executed. An appeals court quickly overturned both stays,[17] and the Supreme Court subsequently rejected final appeals.[18][19]

Franklin was executed at the Eastern Reception, Diagnostic and Correctional Center in Bonne Terre, Missouri on November 20, 2013. The execution began at 6:07 AM CST and he was pronounced dead at 6:17 AM CST.[17] His execution was the first lethal injection in Missouri to use pentobarbital alone instead of the conventional three drug cocktail.[18]

An Associated Press news agency journalist said that Franklin swallowed hard as 5g of pentobarbital were administered. It took him 10 minutes to be pronounced dead.[20]

Racist views 'renounced'

In an interview with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch newspaper published on Monday, November 17, 2013, Franklin said he had renounced his racist views. He said his motivation had been "illogical" and was partly a consequence of an abusive upbringing. He said he had interacted with black people in prison, adding: "I saw they were people just like us."[7]

Michael Newton - An Encyclopedia of Modern Serial Killers - Hunting Humans

Joseph Paul Franklin