26th murderer executed in U.S. in 2014

1385th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Arizona in 2014

37th murderer executed in Arizona since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(26) |

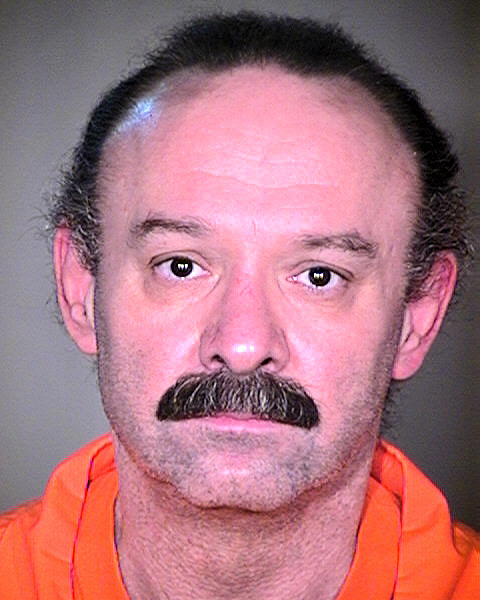

Joseph Rudolph Wood III W / M / 30 - 55 |

Debra Dietz W / W / 29 Eugene Dietz W / M / 55 |

Her Father |

Summary:

Wood and his 29-year-old ex-girlfriend, Debbie Dietz, had been involved in a turbulent relationship for 5 years, which had been marred by numerous breakups and several domestic violent incidents. Dietz tried to end their relationship and got an order of protection against Wood. Debbie was working at a local body shop owned by her family. On August 7, 1989, Wood walked into the shop. waited for her father, Gene Deitz, to hang up the phone, then shot him in the chest with a .38 caliber revolver, killing him. Wood approached Debbie, placed her in some type of hold, and shot her once in the abdomen and once in the chest, killing her. Wood then fled the building. Two police officers approached Wood and ordered him to drop his weapon. After Wood placed the weapon on the ground, he reached down and picked it up, and pointed it at the officers. The officers fired, striking him several times. Wood survived his wounds after extensive surgery.

Citations:

State v. Wood, 180 Ariz. 53, 881 P.2d 1158 (Ariz. 1994).(Direct Appeal)

Wood v. Ryan, 693 F.3d 1104 (9th Cir. 2012). (Habeas)

Wood v. Ryan, ___ F.3d ___ (9th Cir. 2014). (Sec. 1983)

Final Words:

Wood looked at the victim's family as he delivered his final words, saying he was thankful for Jesus Christ as his savior. At one point, he smiled at them, which angered the family. "I take comfort knowing today my pain stops, and I said a prayer that on this or any other day you may find peace in all of your hearts, and may God forgive you all."

Final / Special Meal:

Wood chose not to have a special "last meal" Tuesday night, instead eating the sausage and mashed potatoes that the rest of the prisoners were served.

Internet Sources:

Arizona Department of Corrections

INMATE: WOOD, JOSEPH #086279

Date of Birth: December 6, 1958

Executed: July 23, 2014

Defendant: Caucasian

Last Meal: 2 cookies

Wood and his 29-year-old ex-girlfriend, Debbie Dietz, had been involved in a turbulent relationship for 5 years, which had been marred by numerous breakups and several domestic violent incidents. Debbie was working at a local body shop owned by her family. On August 7, 1989, Wood walked into the shop and shot Gene Dietz, age 55, in the chest with a .38 caliber revolver, killing him. Gene Dietz's 70-year-old brother was present and tried to stop Wood, but Wood pushed him away and proceeded into another section of the body shop. Wood went up to Debbie, placed her in some type of hold, and shot her once in the abdomen and once in the chest, killing her. Wood then fled the building. Two police officers approached Wood and ordered him to drop his weapon. After Wood placed the weapon on the ground, he reached down and picked it up, and pointed it at the officers. The officers fired, striking Wood several times. Wood was transported to a local hospital where he underwent extensive surgery.

PROCEEDINGS:

Presiding Judge: Hon. G. Thomas Meehan

Prosecutor: Thomas Zawada

Defense Counsel: Lamar Couser

Start of Trial: February 19, 1991

Verdict: February 25, 1991

Sentencing: July 2, 1991

Aggravating Circumstances: Grave risk of death to others, Multiple homicides

Published Opinion: State v. Wood, 180 Ariz. 53, 881 P.2d 1158 (1994).

Inmate: WOOD JOSEPH R

DOB: 12/06/1958

Gender: Male

Height 67 in

Weight: 240 lbs

Hair Color:Brown

Eye Color: Brown

Ethnic Origin: Caucasian

Admission: 07/19/1991

Executed: 07/23/2014

Sentence County Court Cause# Offense Date Crime

DEATH PIMA 0028449 08/07/1989 MURDER 1ST DEGREE; DANGER

0150000 PIMA 0028449 08/07/1989 AGGRAVATED ASSAULT; DANGER

0150000 PIMA 0028449 08/07/1989 AGGRAVATED ASSAULT; DANGER

AZCentral - The Arizona Republic

"Reporter describes Arizona execution: 2 hours, 640 gasps," by Michael Kiefer. (11:58 p.m. MST July 26, 2014)

Lethal injection was invented in the United States in 1977. States at that time used an anesthetic called thiopental in combination with other drugs. But in 2010, a shortage of thiopental left states scrambling to obtain deadly drugs. Arizona Republic reporter Michael Kiefer, through use of public-records laws and wide-ranging reporting, documented that Arizona and other states had obtained supplies improperly until their source was cut off, then switched to the barbiturate pentobarbital. But pentobarbital manufacturers soon put in place sales controls to avoid its use for executions. Some halted because assisting in executions is prohibited by European law. And some just didn't want to be known as a company that sells drugs that kill people. By the end of 2013, pentobarbital also became unavailable for executions.

Since then, death-penalty states have been scrambling to come up with alternatives. Some have turned to compounding pharmacies to custom-make pentobarbital; others have turned to midazolam, a drug related to Valium. Executions carried out with midazolam in Florida, Ohio and Oklahoma suggested that the drug worked less quickly and less efficiently in putting people to death than thiopental or pentobarbital. When Arizona announced that it would use midazolam in combination with the narcotic hydromorphone to execute double-murderer Joseph Rudolph Wood, Wood's attorneys fought to the U.S. Supreme Court. The execution took place Wednesday. Kiefer was a news-media witness. What follows is his account of what he saw.

The first glimpse was from above, framed by two closed-circuit TVs. Joseph Rudolph Wood was strapped to a gurney in an orange jumpsuit as prison medical staff prepared to set intravenous lines in his arms. It was 1:30 in the afternoon at Housing Unit 9, the small, one-story, free-standing stucco building where executions are carried out at the Arizona Prison Complex-Florence. The viewing room is 15 feet by 12 feet, painted in calming tones of blue, with three rows of risers that climb from the big window that looks into the lethal-injection chamber in front to the bay windows of the gas chamber behind. Federal law requires that witnesses to executions see every phase, including the setting of IV lines. But in Arizona, it's done on camera.

Wood's eyes flitted back and forth, and his eyebrows arched as men in scrubs, their faces out of camera range, fussed with blood-pressure cuffs and trays of IV needles. The lines went in easily. They don't usually; Arizona is one of three states that will surgically cut a catheter into a condemned man's groin after failing to find veins in the arms or hands, a process used in nine of the past 14 executions. Then, the curtains opened.

According to Arizona Republic reporter Michael Kiefer, Wood was unconscious by 1:57 p.m.. At about 2:05, he started gasping. Wood turned his head and looked curiously at the 20 or so witnesses in the room. He found the family of his victims, the sisters and brother-in-law of Debra Dietz, the estranged girlfriend he killed, along with her father, Eugene, in Tucson in 1989. He grinned, seemed to laugh at them and jerked his head back to look at the ceiling. Next to me, Wood's chaplain, a priest in a collar, counted beads on a rosary. His lips moved silently in prayer. Three of Wood's attorneys sat behind him.

Wood pronounced his last words: There was no apology to the family, only a statement about how he had found Jesus, who he hoped would forgive them all. "Are those your last words?" the warden asked. "Yes, sir." It was 1:54. The drugs had already begun to flow through the IVs. The execution had begun.

This was the fifth execution I've witnessed. They don't look like much. The condemned person usually wears an expression of dumbfounded embarrassment and stares absurdly at the ceiling. Then, his eyes close slowly and he stops moving, except for a few chest-raising breaths that slow and then stop. The face slackens, the mouth gapes. It's usually over in 10 or 11 minutes. Wood's execution was no different — at first. Maybe he was smiling, but just slightly. He took a few gulps of air and closed his eyes. The priest stopped praying and watched

Four minutes into the procedure, the doctor appeared on the other side of the window. He checked Wood's eyes and pulse and then said over the microphone, "It is confirmed that he is sedated." There had been concern about the drugs used in this execution, a cocktail of the Valium-like midazolam and a narcotic called hydromorphone. Witnesses to an execution in Florida, where the drug was used last October, noted that it seemed to take longer than usual. An Ohio execution in January took more than 20 minutes and death-penalty attorneys claimed that was too long.

Wood's attorneys filed motions in state and federal courts expressing concerns over the drugs and the Arizona Department of Corrections' refusal to provide information about the specific batches of the drugs that it had obtained. The execution was stayed twice. The first stay was lifted Tuesday by the U.S. Supreme Court. A second stay was imposed Wednesday morning, which pushed the execution back from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. The Arizona Supreme Court lifted it before noon Wednesday. At the start of Wood's execution, none of those concerns seemed warranted.

Then at 2:05, Wood's mouth opened. Three minutes later it opened again, and his chest moved as if he had burped. Then two minutes again, and again, the mouth open wider and wider. Then it didn't stop. He gulped like a fish on land. The movement was like a piston: The mouth opened, the chest rose, the stomach convulsed. And when the doctor came in to check on his consciousness and turned on the microphone to announce that Wood was still sedated, we could hear the sound he was making: a snoring, sucking, similar to when a swimming-pool filter starts taking in air, a louder noise than I can imitate, though I have tried. It was death by apnea. And it went on for an hour and a half. I made a pencil stroke on a pad of paper, each time his mouth opened, and ticked off more than 640, which was not all of them, because the doctor came in at least four times and blocked my view. I turned to my friend Troy Hayden, the anchor and reporter from Fox 10 News, who was sitting next to me. Troy and I witnessed another execution together in 2007, and he had seen one before that, so he also knows what it looks like. "I don't think he's going to die," I said. A moment later, Troy turned to me and whispered, "I think you're right."

The priest laid a crucifix at the end of the rosary on the bench and stared into the face of Jesus. I wondered if there were a Plan B, some other dose of drugs, something to speed up the death. Or someone to stop it. In fact, as Wood was drowning in air, two of his attorneys left the room. I later learned they had filed motions to try to get the execution stopped. Finally, Wood started to gasp less frequently. Once, twice, minutes apart; he stopped at 3:36. At 3:40 and 3:48, the doctor examined him and pronounced him "still sedated."

A minute later, Arizona Department of Corrections Director Charles Ryan appeared in the window next to Wood's gurney, like some kind of narrator. It was like a scene featuring the stage manager in Thornton Wilder's play, "Our Town." Or maybe like Rod Serling in "Twilight Zone." The execution had been completed, he said. The curtains closed. The witnesses filed out. One of Wood's lawyers said, "The experiment failed."

AZCentral - The Arizona Republic

"Execution of Arizona murderer takes nearly 2 hours," by Bob Ortega, Michael Kiefer and Mariana Dale. (12:24 a.m. MST July 24, 2014)

The controversial drug that Arizona used to execute double-murderer Joseph Rudolph Wood on Wednesday took nearly two hours to kill him and left him snorting and gasping for breath. One reporter who witnessed the execution, Troy Hayden of Fox 10 News, said it was "very disturbing to watch ... like a fish on shore gulping for air. At a certain point, you wondered whether he was ever going to die." State officials and the victims' families, however, took issue with other witness descriptions, saying that Wood was not conscious after the first few minutes and that the noises he made sounded like snoring. According to Arizona Republic reporter Michael Kiefer, Wood was unconscious by 1:57 p.m.. At about 2:05, he started gasping.

Richard Brown claimed the media had more compassion for a convicted killer then the victim. Arizona Attorney General Tom Horne declined to comment. His spokeswoman, Stephanie Grisham, disputed that Wood snorted or gasped for air. "He went to sleep and appeared to be snoring," she said. "This was my first execution, and I was surprised at how peaceful it was." Wood was sentenced to death for the 1989 murders of his ex-girlfriend, Debra Dietz, and her father, Eugene Dietz.

The victims' family members said the media were wrong to focus on the execution method rather than on the victims. "Everybody here said it was excruciating," said Jeanne Brown, Debra Dietz's sister. "You don't know what excruciating is. Seeing your dad lying there in a pool of blood, seeing your sister lying there in a pool of blood, that's excruciating." Her husband, Richard Brown, who said he witnessed the murders, said, "What I've seen today, you guys are blowing this all out of proportion about these drugs. "Why didn't we give him a bullet? Why didn't we give him some Drano? These people that are on death row, they deserve to suffer a little bit."

Across the country, a majority of Americans support the death penalty, but that support appears to be waning. A 2013 Pew Research Center survey indicated that 55 percent of U.S. adults favor the practice, while 37 percent oppose it, a big drop from two years earlier, when 62 percent said they favored the death penalty for murder convictions and 31 percent opposed it. Wednesday's execution began at 1:53 p.m., after Wood's last words, in which he thanked his attorneys, said he had found Christ and concluded, "May God forgive all of you."

According to Arizona Republic reporter Michael Kiefer, who witnessed the execution, lines were run into each of Wood's arms. Wood was unconscious by 1:57 p.m. At about 2:05, he started gasping, Kiefer said. "I counted about 640 times he gasped," Kiefer said. "That petered out by 3:33. The death was called at 3:49. ... I just know it was not efficient. It took a long time."

The length of the process drew swift condemnation from death-penalty critics. "The worst part about Joseph Wood's botched execution was, it was entirely predictable and avoidable," Diann Rust-Tierney, executive director of the National Coalition To Abolish the Death Penalty, said in a statement noting that the same combination of drugs had been used in a problematic execution in Ohio earlier this year. That was echoed by the Arizona director of the American Civil Liberties Union. "Arizona had clear warnings from Ohio and Oklahoma," said Alessandra Soler, executive director of the ACLU of Arizona, calling for a moratorium on executions. "Instead of ensuring that a similar outcome was avoided here, our state officials cloaked the plans for Mr. Wood's death in secrecy."

AZCENTRAL

"Appeals court judge argues for return of firing squads."

The latest petition initially was filed in Pima County Superior Court after a federal appellate court's stay was lifted Tuesday by the U.S. Supreme Court. It argued that Wood had ineffective assistance of counsel during his trial, and also challenged Arizona's lethal-injection protocol and the drug cocktail used in executions. Pima County Superior Court Judge Kenneth Lee dismissed Wood's first argument, but sent the question of Arizona's lethal-injection protocol to the state high court. On Tuesday, the U.S. Supreme Court had upheld Arizona's veil of secrecy around its lethal-injection drugs, permitting plans for the execution to proceed. The high-court ruling knocked down a federal appeals court decision that the execution could not move forward unless the state turned over information about how the execution would be carried out.

Executions are public events. But in recent years, many states that still have capital punishment, including Arizona, have passed or expanded laws that shroud the procedures in secrecy. The Arizona Department of Corrections planned to use a controversial drug, and it favors a controversial method of administering it, so Wood's attorneys demanded to know the qualifications of the executioners and the origin of the drugs to be used in the execution, claiming that Wood had a First Amendment right to the information. On Saturday, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed. The state appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which lifted the stay without addressing the First Amendment issue.

State officials said in court filings that they need to maintain secrecy because publicity has made it more difficult to obtain the drugs needed to carry out executions. Drug manufacturers have begun refusing to sell to departments of corrections, forcing the departments to experiment with new and less reliable drugs or to specially order them from compounding pharmacies, which in turn are harassed by anti-death-penalty activists. "Prisoners who are sentenced to death for their crimes have every right to know what drugs are going to be used," said Stephanie Grisham, a spokeswoman for Arizona Attorney General Tom Horne, "but it would be a bad matter of policy if the manufacturer of these drugs were identified. The very reason we have a new drug protocol is because of the pressure and threats applied to the companies ... forcing them to stop making it."

It was not the first time the Supreme Court has ruled against a stay of execution based on drug secrecy. In 2010, it ruled against an Arizona prisoner asserting his right to know about lethal-injection drugs that turned out to have been improperly obtained from overseas. The U.S. District and Circuit Courts in Washington, D.C., later determined federal law had been violated, which the Arizona Attorney General's Office denies. "In most respects, what Mr. Wood is asking for is quite small," said Megan McCracken, a former federal defender who works with the University of California-Berkeley Death Penalty Clinic. "I think they don't want to set precedent about giving out information, and they don't want to come under scrutiny."

Sen. Ed Ableser, D-Tempe, called the execution barbaric and said: "This one is really on (Brewer's) shoulders. She can sign an executive order, put a stay on executions and let the Legislature find a better way to deal with violent criminals who deserve the maximum penalty, but one that is not cruel and unusual." Dan Peitzmeyer, president of Phoenix-based Death Penalty Alternatives, said, "Actions like this might not cause us to totally repeal the death penalty. But it should sure as hell cause us to bring a moratorium to it and take a sincere look at what we're doing."

Executions by lethal injection using barbiturates such as pentobarbital more typically take about 10 minutes. But the European and American manufacturers refuse to supply it for executions. With the drug unavailable for death penalties, Arizona became the latest of four states to turn to another sedative, midazolam, first used for execution less than a year ago. Arizona used it in combination with a narcotic, hydromorphone. Midazolam, by itself or with hydromorphone, has led to flawed, drawn-out executions in three other states. Wood's attorneys had fought its use before the U.S. Supreme Court and then in a last-minute appeal to the Arizona Supreme Court, saying the drug was "experimental" and had not been proven to be effective.

Wood had been scheduled to die at 10a.m. Wednesday, but the state Supreme Court halted the process to consider a last-minute petition for post-conviction relief. The court lifted its temporary stay shortly before noon, clearing the way for his execution later in the day. Witnesses were told when the stay was issued to return by 1 p.m. One day earlier, it was uncertain whether the execution would go forward. Wood's attorneys had filed for a preliminary injunction to stop the execution unless Arizona revealed where it had obtained the midazolam and divulged the qualifications of the medical team that would administer it.

In October and January, midazolam was used in executions in other states. Both times, witnesses said that the condemned prisoners appeared to gasp for breath and took longer to die than with the barbiturates that were used until they became unavailable. And in April, an Oklahoma inmate was executed using the drug, but the medical person inserting the catheter into a groin artery completely punctured it, sending the drug into the soft tissue beneath. The man writhed in pain for more than 40 minutes before dying of an apparent heart attack. Wood's attorneys asked for information with those incidents in mind. A U.S. District Court judge denied a stay. But on Saturday, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals granted it, with the condition that it would be vacated if the state turned over the information. The Arizona Attorney General's Office appealed the 9th Circuit ruling and the U.S. Supreme Court threw it out Tuesday afternoon. Wood chose not to have a special "last meal" Tuesday night, instead eating the sausage and mashed potatoes that the rest of the prisoners were served.

In 1989, Wood was living with Debra Dietz, who supported him and paid for the apartment they shared. But Wood was abusive, and after Dietz moved out of the apartment, he stalked her. On Aug. 7, 1989, Wood became enraged when Dietz wouldn't take his calls. He went to the auto body shop where Dietz worked for her father. Eugene Dietz was on the phone when Wood reached the body shop; Wood waited for him to hang up and then shot him in the chest without saying a word. Wood then hunted down Debra Dietz and shot her twice in the chest.

"Arizona inmate takes nearly two hours to die in botched execution," by David Schwartz. (Thu Jul 24, 2014 7:37am EDT)

PHOENIX (Reuters) - An Arizona inmate took almost two hours to die by lethal injection on Wednesday and his lawyers said he "gasped and snorted" before succumbing in the latest botched execution to raise questions about the death penalty in the United States. The execution of convicted double murderer Joseph Wood began at 1:52 p.m. at a state prison complex, and the 55-year-old was pronounced dead just shy of two hours later at 3:49 p.m., the Arizona attorney general's office said.

During that time, his lawyers filed an unsuccessful emergency appeal to multiple federal courts that sought to have the execution halted and their client given life-saving medical treatment. The appeal, which said the procedure violated his constitutional right to be executed without suffering cruel and unusual punishment, was denied by Justice Anthony Kennedy of the U.S. Supreme Court. "He gasped and struggled to breathe for about an hour and 40 minutes," said one of Wood's attorneys, Dale Baich. "Arizona appears to have joined several other states who have been responsible for an entirely preventable horror: a bungled execution. The public should hold its officials responsible."

Arizona Governor Jan Brewer expressed concern over how long the procedure took and ordered the state's Department of Corrections to conduct a full review, but said justice had been done and that the execution was lawful. "One thing is certain, however, inmate Wood died in a lawful manner and by eyewitness and medical accounts he did not suffer," the Republican governor said in a statement. "This is in stark comparison to the gruesome, vicious suffering that he inflicted on his two victims, and the lifetime of suffering he has caused their family."

An Arizona Republic journalist who witnessed the execution said he counted the inmate gasping for breath about 660 times. "I just know it was not efficient," said the reporter, Michael Kiefer. "It took a long time."

DRAWN-OUT DEATH

Charles Ryan, director of Arizona's Department of Corrections, said protocol was followed and that the execution was monitored by a team of licensed medical professionals. He said Wood was "fully and deeply sedated" five minutes after the drugs began to be administered, and that the medical team reaffirmed that he remained deeply sedated seven more times before he was pronounced dead. Ryan said in a statement that apart from snoring, Wood "did not grimace or make any further movement."

The Pima County Medical Examiner will conduct an independent autopsy, he said, and a toxicology study was requested too. Wood had been one of six death row prisoners who sued Arizona last month arguing that secrecy surrounding the drugs used in other botched executions in Ohio and Oklahoma violated their rights. But he exhausted his appeals on Wednesday when the Arizona Supreme Court lifted a hold after reviewing a last-minute appeal that involved demands for more information about the lethal drug cocktail to be used in the execution. Wood's lawyers had also wanted to know the qualifications of the medical staff conducting the execution.

Anti-death penalty campaigners expressed horror over the drawn-out death. Cassandra Stubbs, director of the American Civil Liberties Union's Capital Punishment Project, said Arizona had broken constitutional rights, and the bounds of basic decency. "It's time for Arizona and the other states still using lethal injection to admit that this experiment with unreliable drugs is a failure," she said in a statement. Diann Rust-Tierney, executive director of the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, said Wood's execution had been shocking, cruel and entirely predictable. "Americans have had enough of the barbarism," she said.

In January, convicted rapist and murderer Dennis McGuire was put to death in Ohio using a sedative-painkiller mix of midazolam and hydromorphone, the first such combination administered for a lethal injection in the United States. The execution took about 25 minutes to complete, with McGuire reportedly convulsing and gasping for breath. In Oklahoma in April, convicted killer Clayton Lockett writhed in pain and a needle became dislodged during his lethal injection at a state prison. The execution was halted, but Lockett died about 30 minutes later of a heart attack.

"Doctor: Injection lines placed correctly in inmate."

PHOENIX (AP) — Intravenous lines were placed correctly during the execution of an Arizona inmate whose death with lethal drugs took more than 90 minutes, a medical examiner said Monday. Incorrect placement of lines can inject drugs into soft tissue instead of the blood stream, but the drugs used to kill Joseph Woods went into the veins of his arms, said Gregory Hess of the Pima County Medical Examiner's Office. Hess also told The Associated Press that he found no unexplained injuries or anything else out of the ordinary when he examined the body of Woods, who gasped and snorted Wednesday more than 600 times before he was pronounced dead.

An Ohio inmate gasped in similar fashion for nearly 30 minutes in January. An Oklahoma inmate died of a heart attack in April, minutes after prison officials halted his execution because the drugs weren't being administered properly.

Hess said he will certify the outcome of Woods' execution as death by intoxication from the two execution drugs — the sedative midazolam and the painkiller hydromorphone — if there is nothing unusual about whatever drugs are detected in Wood's system. Hess' preliminary findings were reported previously by the Arizona Capitol Times (http://bit.ly/1thLaFe ). Toxicology results are expected in 4 to 6 weeks from an outside lab. Hess is chief deputy medical examiner for Pima County, which conducts autopsies for Pinal County, where the prison is located.

Wood was sentenced to death for the 1989 killings of his estranged girlfriend, Debbie Dietz, and her father, Gene Dietz. Wood was the first Arizona prisoner to be killed with the drug combination. Anesthesiology experts have said they weren't surprised the drugs took so long to kill him. Arizona and other death-penalty states have scrambled in recent years to find alternatives to drugs used previously for executions but are now in short supply due to opposition to capital punishment. Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer has ordered the Corrections Department to conduct a review of the execution of Wood.

"As inmate died, lawyers argued whether he was in pain." (July 24, 2014)

FLORENCE, Ariz. (AP) - The nearly two-hour execution of a convicted murderer prompted a series of phone calls involving the governor's office, the prison director, lawyers and judges as the inmate gasped for more than 90 minutes. They discussed the brain activity and heart rate of Joseph Rudolph Wood, who was gasping over and over as witnesses looked on. The judge was concerned that no monitoring equipment showed whether the inmate had brain function, and they talked about whether to stop the execution while it was so far along.

But the defense lawyers' pleading on the grounds that Wood could be suffering while strapped to a gurney, breathing in and out and snoring, did no good. Nearly two hours after he'd been sedated Wednesday, Wood finally died. A transcript of an emergency court hearing released Thursday amid debate over whether the execution was botched reveals the behind-the-scenes drama and early questions about whether something was going wrong.

Department of Corrections Director Charles Ryan read a statement Thursday outside his office dismissing the notion the execution was botched, calling it an "erroneous conclusion" and "pure conjecture." He said IV lines in the inmate's arms were "perfectly placed" and insisted that Wood felt no pain. But he also said the Arizona attorney general's office will not seek any new death warrants while his office completes a review of execution practices. He didn't take questions from reporters.

Defense lawyer Dale Baich called it a "horrifically botched execution" that should have taken 10 minutes. U.S. District Judge Neil V. Wake convened the urgent hearing at the request of one of Wood's attorneys, notified by her colleagues at the execution that things were problematic. A lawyer for the state, Jeffrey A. Zick, assured Wake that Wood was comatose and not feeling pain. He spoke to the Arizona Department of Corrections director on the phone and was given assurances from medical staff at the prison that Wood was not in any pain. Zick also said the governor's office was notified of the situation.

Zick said that at one point, a second dose of drugs was given, but he did not provide specifics. The participants discussed Wood's brain activity and heart rate. "I am told that Mr. Wood is effectively brain dead and that this is the type of reaction that one gets if they were taken off of life support. The brain stem is working but there's no brain activity," he said, according to the transcript. The judge then asked, "Do you have the leads connected to determine his brain state?" The lawyer said he didn't think so. "Well if there are not monitors connected with him, if it's just a visual observation, that is very concerning as not being adequate," the judge said.

Wood died at 3:49 p.m., and judges were notified of his death while they were still considering whether to stop it. Zick later informed the judge that Wood had died. Anesthesiology experts say they're not surprised that the combination of drugs took so long to kill Wood. "This doesn't actually sound like a botched execution. This actually sounds like a typical scenario if you used that drug combination," said Karen Sibert, an anesthesiologist and associate professor at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Sibert was speaking on behalf of the California Society of Anesthesiologists. Sibert said the sedative midazolam would not completely render Wood incapacitated. If he'd felt pain or been conscious, he would have been able to open his eyes and move, she said. The other drug was the painkiller hydromorphone. "It's fair to say that those are drugs that would not expeditiously achieve (death)," said Daniel Nyhan, a professor and interim director at the anesthesiology department at Johns Hopkins medical school.

But the third execution in six months to appear to go awry rekindled the debate over the death penalty and handed potentially new evidence to those building a case against lethal injection as cruel and unusual punishment. An Ohio inmate gasped in similar fashion for nearly 30 minutes in January. An Oklahoma inmate died of a heart attack in April, minutes after prison officials halted his execution because the drugs weren't being administered properly.

Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer said later that she was ordering a review of the state's execution process, saying she's concerned by how long it took for the drug protocol to kill Wood. Family members of Wood's victims in a 1989 double murder said they had no problems with the way the execution was carried out. "This man conducted a horrific murder and you guys are going, 'let's worry about the drugs,'" said Richard Brown, the brother-in-law of Debbie Dietz. "Why didn't they give him a bullet? Why didn't we give him Drano?"

Arizona uses the same drugs that were used in the Ohio execution. A different drug combination was used in the Oklahoma case. States have refused to reveal details such as which pharmacies are supplying lethal injection drugs and who is administering them out of concerns that the drugmakers could be harassed. Wood filed several appeals that were denied by the U.S. Supreme Court. Wood argued he and the public have a right to know details about the state's method for lethal injections, the qualifications of the executioner and who makes the drugs. Such demands for greater transparency have become a legal tactic in death penalty cases.

Wood was convicted of fatally shooting Dietz, 29, and her father, Gene Dietz, 55, at their auto repair shop in Tucson.

"Inside the Efforts to Halt Arizona’s Two-Hour Execution of Joseph Wood," by Josh Sanburn. (July 24, 2014)

The inmate's lawyers appealed to state and federal courts to issue an order to resuscitate Wood as he reportedly gasped on the gurney on Wednesday An hour into Joseph Wood’s execution, as the condemned prisoner gasped for air and struggled to breathe, Wood’s attorneys were filing motions in federal district court and the state supreme court in an attempt to get an order to resuscitate the death-row inmate as he lay on the gurney. “We were arguing that he was still alive, that we did not know his level of sedation, and that he was still breathing,” says Dale Baich, one of Wood’s attorneys, who witnessed Wednesday’s prolonged execution.

Wood’s lethal injection, almost two hours long, is the third execution this year widely considered “botched,” raising new questions surrounding the efficacy of the method as state officials once again pledge an investigation into why it went awry. Wood’s lawyers attempted to get a stay for his execution, based initially on First Amendment grounds that Wood, convicted of murdering his ex-girlfriend and her father in 1989, had a right to know the origins of the execution drugs being used. The U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals sided with Wood and issued a stay, but the Supreme Court lifted it. In a last-minute appeal, Wood’s attorneys argued that the drugs posed a risk of violating the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, but the Arizona Supreme Court failed to grant a stay.

At 1:52 p.m. on Wednesday, Wood was led into the execution chamber and strapped to the gurney. Midazolam, a sedative, and hydromorphone, used to halt breathing, were administered. About five minutes into the process, Baich says, a medical-team member came into the chamber and announced that Wood was unconscious. But his condition soon changed. “About two or three minutes later, I noticed his lips moved slightly,” Baich says. “And then two minutes after that, he was gasping for air. He started breathing. And he was pressing up against the restraining straps. And that went on for about an hour.” Baich says Wood was taking deep, long breaths — “like he was gasping, like he was drowning.” He adds that someone from the department of corrections’ medical staff checked on Wood seven times throughout the two-hour process. Michael Kiefer, a writer for the Arizona Republic, reported that Wood gasped 640 times.

Meanwhile, Baich was filtering information to another attorney, who was filing a motion in U.S. District Court and the Arizona Supreme Court in an attempt to get an order to resuscitate the inmate. Wood died during the hearings. Arizona Governor Jan Brewer has asked for a review of the state’s lethal-injection process, saying she was “concerned by the length of the time it took” to complete the execution but denied that Wood was in pain. “One thing is certain, however, inmate Wood died in a lawful manner and by eyewitness and medical accounts he did not suffer,” Brewer said in a statement.

Wood’s execution appeared to be eerily similar to that of Dennis McGuire, a convicted murderer who was executed in Ohio with the same drug combination used in Arizona. McGuire reportedly made snoring noises, similar to the ones made by Wood, during his 25-minute execution. Lethal-injection executions generally take 10 to 15 minutes to complete.

Joseph Wood shot and killed his estranged girlfriend, Debra Dietz, and her father, Eugene Dietz, on August 7, 1989 at a Tucson automotive paint and body shop owned and operated by the Dietz family. Since 1984, Wood and Debra had maintained a tumultuous relationship increasingly marred by Wood's abusive and violent behavior. Eugene generally disapproved of this relationship but did not actively interfere. In fact, the Dietz family often included Wood in dinners and other activities. Several times, however, Eugene refused to let Wood visit Debra during business hours while she was working at the shop.

Wood disliked Eugene and told him he would “get him back” and that Eugene would “be sorry.” Debra had rented an apartment that she shared with Wood. Because Wood was seldom employed, Debra supported him financially. Wood nevertheless assaulted Debra periodically. She finally tried to end the relationship after a fight during the 1989 July 4th weekend. She left her apartment and moved in with her parents, saying “I don't want any more of this.” After Debra left, Wood ransacked and vandalized the apartment. She obtained an order of protection against Wood on July 8, 1989.

In the following weeks, however, Wood repeatedly tried to contact Debra at the shop, her parents' home, and her apartment. Debra and Eugene drove together to work at the shop early on Monday morning, August 7, 1989. Wood phoned the shop three times that morning. Debra hung up on him once, and Eugene hung up on him twice. Wood called again and asked another employee if Debra and Eugene were at the shop. The employee said that they had temporarily left but would return soon. Debra and Eugene came back at 8:30 a.m. and began working in different areas of the shop. Six other employees were also present that morning. At 8:50 a.m., a Tucson Police officer saw Wood driving in a suspicious manner near the shop. The officer slowed her patrol car and made eye contact with Wood as he left his truck and entered the shop.

Eugene was on the telephone in an area where three other employees were working. Wood waited for Eugene to hang up, drew a revolver, and approached to within four feet of him. The other employees shouted for Wood to put the gun away. Without saying a word, Wood fatally shot Eugene once in the chest and then smiled. When the police officer saw this from her patrol car she immediately called for more officers. Wood left the shop, but quickly returned and again pointed his revolver at the now supine Eugene. Donald Dietz, an employee and Eugene's seventy-year-old brother, struggled with Wood, who then ran to the area where Debra had been working. Debra had apparently heard an employee shout that her father had been shot and was trying to telephone for help when Wood grabbed her around the neck from behind and placed his revolver directly against her chest. Debra struggled and screamed, “No, Joe, don't!” Another employee heard Wood say, “I told you I was going to do it, I have to kill you.” Wood then called Debra a “bitch” and shot her twice in the chest.

Several police officers were already on the scene when Wood left the shop after shooting Debra. Two officers ordered him to put his hands up. Wood complied and dropped his weapon, but then grabbed it and began raising it toward the officers. After again ordering Wood to raise his hands, the officers shot Wood several times. Wood was arrested and indicted on two counts of first degree murder and two counts of aggravated assault against the police officers who subdued him.

At trial, Wood conceded his role in the killings, but argued that they were impulsive acts that were not premeditated. After a five-day trial, the jury found Wood guilty on all counts. Following an aggravation and mitigation hearing, the trial court sentenced Wood to imprisonment for the assaults and to death for each murder.

Arizona Death Row Prisoners Slideshow (AZCentral.Com)

Arizona's History of Executions since 1992 (AZCentral.Com)

Wikipedia: List of People executed in Arizona Since 1976

1. Donald Eugene Harding White 43 M 06-Apr-1992 Lethal gas Allen Gage, Robert Wise, and Martin Concannon

2. John George Brewer White 27 M 03-Mar-1993 Lethal injection Rite Brier

3. James Dean Clark White 35 M 14-Apr-1993 Lethal injection Charles Thumm, Mildred Thumm, Gerald McFerron, and George Martin

4. Jimmie Wayne Jeffers White 49 M 13-Sep-1995 Lethal injection Penelope Cheney

5. Darren Lee Bolton White 29 M 19-Jun-1996 Lethal injection Zosha Lee Picket

6. Luis Morine Mata Latino 45 M 22-Aug-1996 Lethal injection Debra Lee Lopez

7. Randy Greenawalt White 47 M 23-Jan-1997 Lethal injection John Lyons, Donnelda Lyons, Christopher Lyons, and Theresa Tyson

8. William Lyle Woratzeck White 51 M 25-Jun-1997 Lethal injection Linda Leslie

9. Jose Jesus Ceja Latino 42 M 21-Jan-1998 Lethal injection Linda Leon and Randy Leon

10. Jose Roberto Villafuerte Latino 45 M 22-Apr-1998 Lethal injection Amelia Shoville

11. Arthur Martin Ross White 43 M 29-Apr-1998 Lethal injection James Ruble

12. Douglas Edward Gretzler White 47 M 03-Jun-1998 Lethal injection Michael Sandsberg and Patricia Sandsberg

13. Jesse James Gillies White 38 M 13-Jan-1999 Lethal injection Suzanne Rossetti

14. Darick Leonard Gerlaugh Native American 38 M 03-Feb-1999 Lethal injection Scott Schwartz

15. Karl-Heinz LaGrand White 35 M 24-Feb-1999 Lethal injection Kenneth Hartsock

16. Walter Bernhard LaGrand White 37 M 03-Mar-1999 Lethal gas

17. Robert Wayne Vickers White 41 M 05-May-1999 Lethal injection Wilmar Holsinger

18. Michael Kent Poland White 59 M 16-Jun-1999 Lethal injection Cecil Newkirk and Russell Dempsey

19. Ignacio Alberto Ortiz Latino 57 M 27-Oct-1999 Lethal injection Manuelita McCormack

20. Anthony Lee Chaney White 45 M 16-Feb-2000 Lethal injection John B. Jamison

21. Patrick Gene Poland White 50 M 15-Mar-2000 Lethal injection Cecil Newkirk and Russell Dempsey

22. Donald Jay Miller White 36 M 08-Nov-2000 Lethal injection Jennifer Geuder

23. Robert Charles Comer White 50 M 22-May-2007 Lethal injection Larry Pritchard and Tracy Andrews

24. Jeffrey Timothy Landrigan Native American 50 M 26-Oct-2010 Lethal injection Chester Dean Dyer

25. Eric John King African American 47 M 29-Mar-2011 Lethal injection Ron Barman and Richard Butts

26. Donald Beaty White 25-May-2011 Lethal Injection Christy Ann Fornoff

27. Richard Lynn Bible 30-June-2011 Lethal Injection Jennifer Wilson

28. Thomas Paul West 19-July-2011 Lethal Injection Don Bortle

29. Robert Henry Moorman 29-Feb-2012 Lethal injection Roberta Maude Moorman

30. Robert Charles Towery 08-Mar-2012 Lethal injection Mark Jones

31. Thomas Arnold Kemp 25-Apr-2012 Lethal injection Hector Juarez

32. Samuel Lopez 27-June-2012 Lethal Injection Estafana Holmes

33. Daniel Wayne Cook 8-August-2012 Lethal Injection Carlos Froyan Cruz-Ramos. Kevin Swaney

34. Richard Dale Stokley 5-December-2012 Lethal Injection Mary Snyder, Mandy Meyers

35. Edward Harold Schad 9-October-2013 Lethal Injection Lorimer Grove

36. Robert Glen Jones Jr. 23-October-2013 Lethal Injection Chip O'Dell, Tom Hardman, Maribeth Munn, Carol Noel, Judy Bell, Arthur 'Taco' Bell

37. Joseph Rudolph Wood III 23-Jul-2014 Lethal injection Debbie Dietz, Gene Dietz

State v. Wood, 180 Ariz. 53, 881 P.2d 1158 (Ariz. 1994).(Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder and two counts of aggravated assault and sentenced to death for each murder after jury trial in the Superior Court, Pima County, No. CR–28449, Thomas Meehan, J. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, Feldman, C.J., held that: (1) defendant's prior physical abuse of and threats against victim were relevant to show state of mind and were properly admitted; (2) hearsay statements about victim's fear and desire to end relationship with defendant were admissible to explain defendant's motive under exception to hearsay for then existing state of mind, emotion, or intent; (3) error in admitting neighbor's testimony that victim had told her that defendant had threatened her life was harmless; (4) evidence was sufficient to support aggravated assault conviction; and (5) aggravating circumstances outweighed mitigating circumstances requiring imposition of death penalty. Affirmed.

FELDMAN, Chief Justice.

A Pima County jury convicted Joseph Rudolph Wood, III (“Defendant”) of two counts of first degree murder and two counts of aggravated assault. The trial court sentenced him to death for each murder and to imprisonment for the assaults. Appeal to this court from the death sentences is automatic. Ariz.R.Crim.P. 26.15, 31.2(b). We have jurisdiction under Ariz. Const. art. VI, § 5(3), A.R.S. §§ 13–4031 and 13–4033(A), and Ariz.R.Crim.P. 31.

FACTS AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY

Defendant shot and killed his estranged girlfriend Debra Dietz (“Debra”) and her father Eugene Dietz (“Eugene”) on Monday, August 7, 1989, at a Tucson automotive paint and body shop (“the shop”) owned and operated by the Dietz family. Since 1984, Defendant and Debra had maintained a tumultuous relationship increasingly marred by Defendant's abusive and violent behavior. Eugene generally disapproved of this relationship but did not actively interfere. In fact, the Dietz family often included Defendant in dinners and other activities. Several times, however, Eugene refused to let Defendant visit Debra during business hours while she was working at the shop. Defendant disliked Eugene and told him he would “get him back” and that Eugene would “be sorry.” Debra had rented an apartment that she shared with Defendant. Because Defendant was seldom employed, Debra supported him financially. Defendant nevertheless assaulted Debra periodically.FN1 She finally tried to end the relationship after a fight during the 1989 July 4th weekend. She left her apartment and moved in with her parents, saying “I don't want any more of this.” After Debra left, Defendant ransacked and vandalized the apartment. She obtained an order of protection against Defendant on July 8, 1989. In the following weeks, however, Defendant repeatedly tried to contact Debra at the shop, her parents' home, and her apartment.FN2

FN1. Debra was often bruised and sometimes wore sunglasses to hide blackened eyes. A neighbor who often heard “thuds and banging” within Debra's apartment called police on June 30, 1989, after finding Debra outside and “hysterical.” The responding officer saw cuts and bruises on Debra. FN2. Defendant left ten messages on Debra's apartment answering machine on the night of Friday, August 4, 1989. Some contained threats of harm, such as: “Debbie, I'm sorry I have to do this. I hope someday somebody will understand when we're not around no more. I do love you babe. I'm going to take you with me.”

Debra and Eugene drove together to work at the shop early on Monday morning, August 7, 1989. Defendant phoned the shop three times that morning. Debra hung up on him once, and Eugene hung up on him twice. Defendant called again and asked another employee if Debra and Eugene were at the shop. The employee said that they had temporarily left but would return soon. Debra and Eugene came back at 8:30 a.m. and began working in different areas of the shop. Six other employees were also present that morning. At 8:50 a.m., a Tucson Police officer saw Defendant driving in a suspicious manner near the shop. The officer slowed her patrol car and made eye contact with Defendant as he left his truck and entered the shop. Eugene was on the telephone in an area where three other employees were working. Defendant waited for Eugene to hang up, drew a revolver, and approached to within four feet of him. The other employees shouted for Defendant to put the gun away. Without saying a word, Defendant fatally shot Eugene once in the chest and then smiled. When the police officer saw this from her patrol car she immediately called for more officers. Defendant left the shop, but quickly returned and again pointed his revolver at the now supine Eugene. Donald Dietz, an employee and Eugene's seventy-year-old brother, struggled with Defendant, who then ran to the area where Debra had been working.

Debra had apparently heard an employee shout that her father had been shot and was trying to telephone for help when Defendant grabbed her around the neck from behind and placed his revolver directly against her chest. Debra struggled and screamed, “No, Joe, don't!” Another employee heard Defendant say, “I told you I was going to do it, I have to kill you.” Defendant then called Debra a “bitch” and shot her twice in the chest. Several police officers were already on the scene when Defendant left the shop after shooting Debra. Two officers ordered him to put his hands up. Defendant complied and dropped his weapon, but then grabbed it and began raising it toward the officers. After again ordering Defendant to raise his hands, the officers shot Defendant several times.

A grand jury indicted Defendant on two counts of first degree murder and two counts of aggravated assault against the officers. Although he did not testify, Defendant did not dispute his role in the killings but argued he had acted impulsively and without premeditation. A jury found Defendant guilty on all counts. The trial court sentenced him to death for each of the murders and to concurrent fifteen-year prison terms for the aggravated assaults, to be served consecutively to the death sentences. This appeal followed.

DISCUSSION

A. Trial issues

Defendant makes many ineffective assistance of counsel claims. Such claims generally should be pursued in post-conviction relief proceedings pursuant to Ariz.R.Crim.P. 32. Because they are fact-intensive and often involve matters of trial tactics and strategy, trial courts are far better-situated to address these issues. State v. Valdez, 160 Ariz. 9, 14–15, 770 P.2d 313, 318–19 (1989). We decline to address them here and turn instead to the other issues presented.

1. Admission of alleged “other act,” hearsay, and irrelevant testimony

Defendant alleges that the trial court improperly admitted testimony from various witnesses, violating his confrontation and due process rights. Unfortunately, appellate counsel has failed to articulate separate grounds of objection to each portion of testimony.FN3 We will, therefore, separate and address the challenged testimony in seven categories. Because the trial court is in the best position to judge the admissibility of proffered testimony, we review most evidentiary claims on a discretionary standard. See, e.g., State v. Prince, 160 Ariz. 268, 274, 772 P.2d 1121, 1127 (1989); State v. Chapple, 135 Ariz. 281, 297 n. 18, 660 P.2d 1208, 1224 n. 18 (1983). FN3. Defense counsel reproduced 20 excerpts of trial testimony amounting to 14 pages in his opening brief and then made a generic claim that all the testimony was improperly admitted on hearsay, relevance, opinion testimony, or Rule 404 grounds. To say the least, this is an unhelpful appellate practice. On appeal, counsel must clearly identify the objectionable portions of testimony and the specific basis for each claimed error. See Ariz.R.Crim.P. 31.13(c)(1)(iv). Because this is a capital case and we must search for fundamental error, we will examine the evidentiary claims before considering the question of any waiver by appellate counsel.

a. Character evidence and prior acts

The trial court denied Defendant's motion to suppress evidence of his prior bad acts. Defendant alleges that the trial court improperly admitted testimony concerning his alleged violent acts against Debra in violation of Ariz.R.Evid. 404(a). We disagree. Rule 404(a) generally precludes admission of other acts to prove a defendant's character or “to show action in conformity therewith” on a particular occasion. State v. Bible, 175 Ariz. 549, 575, 858 P.2d 1152, 1178, cert. denied, 511 U.S. 1046, 114 S.Ct. 1578, 128 L.Ed.2d 221 (1993). Evidence of certain types of prior acts is admissible, however, “for other purposes such as proof of motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, plan, knowledge, identity, or absence of mistake or accident.” Ariz.R.Evid. 404(b). This list of permissible purposes is merely illustrative, not exclusive. State v. Jeffers, 135 Ariz. 404, 417, 661 P.2d 1105, 1118 (1983), cert. denied, 464 U.S. 865, 104 S.Ct. 199, 78 L.Ed.2d 174 (1983), rev'd on other grounds, Jeffers v. Ricketts, 832 F.2d 476, 480–81 (9th Cir.1987); Morris K. Udall et al., Arizona Practice–Law of Evidence § 84, at 179 n. 6 (3d ed. 1991).

This court has “long held that where the existence of premeditation is in issue, evidence of previous quarrels or difficulties between the accused and the victim is admissible.” Jeffers, 135 Ariz. at 418, 661 P.2d at 1119 (citing Leonard v. State, 17 Ariz. 293, 151 P. 947 (1915)). Such evidence “tends to show the malice, motive or premeditation of the accused.” Id. at 418, 661 P.2d at 1119 (emphasis added). In some cases, of course, such evidence may also show lack of premeditation. In either event, it is relevant. Defendant's abuse of Debra falls squarely within this rule and, under the facts of this case, tends to show both motive and premeditation. Premeditation was the main trial issue. The defense was lack of motive to kill either victim and the act's alleged impulsiveness, which supposedly precluded the premeditation required for first degree murder. See A.R.S. § 13–1105(A)(1). Defendant's prior physical abuse of and threats against Debra were relevant to show his state of mind and thus were properly admitted under Rule 404(b). See State v. Featherman, 133 Ariz. 340, 344–45, 651 P.2d 868, 872–73 (Ct.App.1982) (evidence of prior assault on victim admissible to show defendant's intent in murder prosecution).

b. Hearsay statements of Debra Dietz

A number of witnesses testified to statements made by Debra about her fear of Defendant and her desire to end their relationship. Defendant claims the trial court erred in admitting this testimony over a continuing objection that the statements were irrelevant and hearsay.FN4 We address each contention. FN4. The trial court denied Defendant's pretrial motion to suppress all hearsay testimony relating to statements by Debra and recorded defense counsel's continuing objection to such testimony. This is a proper method of preserving error for appeal. State v. Christensen, 129 Ariz. 32, 36, 628 P.2d 580, 584 (1981).

Evidence is relevant “if it has any basis in reason to prove a material fact in issue or if it tends to cast light on the crime charged.” State v. Moss, 119 Ariz. 4, 5, 579 P.2d 42, 43 (1978); Ariz.R.Evid. 401. We have found similar testimony relevant in analogous cases. For instance, in State v. Fulminante, evidence of the victim's fear of the defendant and their acrimonious relationship was relevant to the defendant's motive and admissible to refute defense claims that the relationship was harmonious. 161 Ariz. 237, 251, 778 P.2d 602, 616 (1989), aff'd, 499 U.S. 279, 111 S.Ct. 1246, 113 L.Ed.2d 302 (1991).FN5 Contrary to Defendant's assertion, State v. Charo, 156 Ariz. 561, 754 P.2d 288 (1988), and State v. Christensen, 129 Ariz. 32, 628 P.2d 580 (1981), are consistent with this general rule. Those cases hold merely that evidence of the victim's fear of the defendant is not relevant to prove the defendant's conduct or identity. Charo, 156 Ariz. at 564–65, 754 P.2d at 291–92; Christensen, 129 Ariz. at 36, 628 P.2d at 584. In the present case, by contrast, Defendant's conduct and identity were undisputed. FN5. Other jurisdictions follow this approach. See, e.g., United States v. Donley, 878 F.2d 735, 738 (3d Cir.1989) (victim's statements regarding plan to end relationship relevant to defendant's mental state in murder prosecution), cert. denied, 494 U.S. 1058, 110 S.Ct. 1528, 108 L.Ed.2d 767 (1990); State v. Payne, 327 N.C. 194, 394 S.E.2d 158, 165, cert. denied, 498 U.S. 1092, 111 S.Ct. 977, 112 L.Ed.2d 1062 (1990).

The statements about Debra's fear and desire to end the relationship helped explain Defendant's motive. The disputed trial issues were Defendant's motive and mental state—whether Defendant acted with premeditation or as a result of a sudden impulse. The prosecution theorized that Defendant was motivated by anger or spite engendered by Debra's termination of the relationship.FN6 Debra's statements were relevant because they showed her intent to end the relationship, which in turn provided a plausible motive for premeditated murder. See Fulminante, 161 Ariz. at 251, 778 P.2d at 616. In addition, Debra's statements were also relevant to refute Defendant's assertion that he and Debra had secretly maintained their relationship after July 4, 1989. Id. FN6. Immediately after the murders, Defendant repeatedly said that “if he and Debra couldn't be together in life, they would be together in death.”

Defendant contends that even if the statements were relevant, they were still inadmissible hearsay. Although hearsay, these statements fall within a well-established exception allowing admission of hearsay statements concerning the declarant's then-existing state of mind, emotion, or intent, if the statements are not offered to prove the fact remembered or believed by the declarant. Ariz.R.Evid. 803(3). Debra's statements were not offered to prove any fact. Instead, they related solely to her state of mind when the statements were made and thus fit within the Rule 803(3) exception. Fulminante, 161 Ariz. at 251, 778 P.2d at 616 (victim's desire to move from defendant's home properly admitted under Rule 803(3)). The trial court did not err in admitting this testimony.

c. The neighbor's testimony

The following exchange occurred during the state's direct examination of a neighbor who lived next to the apartment shared by Defendant and Debra: Q. Did she [Debra] ever have another conversation with you later on when she related the same information to you? A. Yes, she did. I remember that instance very clearly ... she told me that she did not want to stay at the apartment because Joe had threatened her life. FN7 FN7. Reporter's Transcript (“R.T.”), Feb. 20, 1991, at 46–47 (emphasis added).

Neither Defendant nor the state addressed why this particular testimony may have been offered, either at trial or on appeal. The statement that Defendant had threatened Debra does not reflect Debra's state of mind but rather appears to be a statement of “memory or belief to prove the fact remembered or believed.” Ariz.R.Evid. 803(3). This declaration therefore falls outside the state of mind exception and should not have been admitted. Charo, 156 Ariz. at 563–64, 754 P.2d at 190–91; Christensen, 129 Ariz. at 36, 628 P.2d at 584. Defendant preserved this claim by his continuing objection at trial, so we must consider the effect of its admission.

We review a trial court's erroneous admission of testimony under a harmless error standard. Bible, 175 Ariz. at 588, 858 P.2d at 1191. Unless an error amounts to a structural defect, it is harmless if we can say “beyond a reasonable doubt that the error had no influence on the jury's judgment.” Id.; see also Sullivan v. Louisiana, 508 U.S. 275, ––––, 113 S.Ct. 2078, 2081, 124 L.Ed.2d 182 (1993) (error is only harmless if guilty verdict “was surely unattributable to the error”). We consider particular errors in light of the totality of the trial evidence. State v. White, 168 Ariz. 500, 508, 815 P.2d 869, 877 (1991), cert. denied, 502 U.S. 1105, 112 S.Ct. 1199, 117 L.Ed.2d 439 (1992). An error that requires reversal in one case may be harmless in another due to the fact-specific nature of the inquiry. Bible, 175 Ariz. at 588, 858 P.2d at 1191. Premeditation was the key trial issue, and we recognize that a prior threat is relevant to that issue. Premeditation requires proof that the defendant “made a decision to kill prior to the act of killing.” State v. Kreps, 146 Ariz. 446, 449, 706 P.2d 1213, 1216 (1985). The interval, however, can be short. Id. Either direct or circumstantial evidence may prove premeditation. State v. Hunter, 136 Ariz. 45, 48, 664 P.2d 195, 198 (1983).

Initially, we note that a tendency to act impulsively in no way precludes a finding of legal premeditation. Defendant offered little evidence to support his claim that he acted without premeditation on the morning of the murders. A defense expert briefly testified that Defendant displayed no signs of organic brain damage or psychotic thinking. The essence of his testimony militating against premeditation was that Defendant “appeared to be an individual that would act in an impulsive fashion, responding more to emotions rather than thinking things out.” This expert, however, examined Defendant for a total of six hours more than thirteen months after the murders, and there was no testimony correlating this trait to Defendant's conduct on August 7, 1989. Other witnesses testified that Defendant had, at various times, acted violently for no apparent reason. These instances usually occurred, however, when Defendant had been abusing alcohol or drugs. There was no evidence that Defendant consumed alcohol or drugs before the murders. There was, on the other hand, a great deal of evidence that unequivocally compels the conclusion that Defendant acted with premeditation. See Bible, 175 Ariz. at 588, 858 P.2d at 1191. Defendant disliked and had threatened Eugene. Three days before the killing, Defendant left threatening phone messages with Debra showing his intent to harm her.FN8 Defendant called the shop just before the killings and asked whether Debra and Eugene were there. Although Defendant regularly carried a gun, on the morning of the murders he also had a spare cartridge belt with him, contrary to his normal practice. Defendant calmly waited for Eugene to hang up the telephone before shooting him. There was no evidence that Eugene did or said anything to which Defendant might have impulsively responded. Finally, Defendant looked for Debra after shooting Eugene, found her in a separate area, and held her before shooting her, stating, “I told you I was going to do it, I have to kill you.” FN8. See supra, note 2.

The hearsay statement about threats came from the state's first witness on the first day of a five-day trial. The prosecutor neither emphasized it nor asked the witness to elaborate. Nor did the prosecutor mention the statement in closing argument. Cf. Charo, 156 Ariz. at 563, 754 P.2d at 190 (noting prosecution's emphasis of improperly-admitted evidence during closing argument in finding reversible error). We note, also, that other statements, properly admitted, established that Defendant had threatened Debra on other occasions. We stress that this court cannot and does not determine an error is harmless merely because the record contains sufficient untainted evidence. Bible, 175 Ariz. at 590, 858 P.2d at 1193. Given this record, however, we are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the statement did not influence the finding of premeditation implicit in the verdict. See State v. Coey, 82 Ariz. 133, 142, 309 P.2d 260, 269 (1957) (finding no reversible error in admission of hearsay statement bearing on pre-meditation). The error was harmless.

d. Constitutional claims

Defendant urges that admission of this and other hearsay statements violated his right to confront witnesses in contravention of the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments. The state claims that Defendant failed to properly raise this claim in either this or the trial court. We need not reach these issues, however, because of our disposition of Defendant's hearsay claims. There is no Confrontation Clause violation when the hearsay testimony of a deceased declarant is admitted pursuant to a firmly-rooted hearsay exception. White v. Illinois, 502 U.S. 346, 356, 112 S.Ct. 736, 743, 116 L.Ed.2d 848 (1992); Bible, 175 Ariz. at 596, 858 P.2d at 1199. The Rule 803(3) state of mind exception is such a recognized exception. See, e.g., Lenza v. Wyrick, 665 F.2d 804, 811 (8th Cir.1981). Additionally, as in this case, a Confrontation Clause violation can be harmless error. Harrington v. California, 395 U.S. 250, 253, 89 S.Ct. 1726, 1728, 23 L.Ed.2d 284 (1969); State v. Wilhite, 160 Ariz. 228, 233, 772 P.2d 582, 587 (Ct.App.1989).

e. Hearsay statements of Eugene Dietz

Defendant alleges next that several witnesses improperly testified about hearsay statements made by Eugene Dietz. To the extent these statements concerned Eugene's state of mind about the animosity between him and Defendant, the statements, like Debra's, were relevant and properly admitted under Rule 803(3). See Fulminante, 161 Ariz. at 251, 778 P.2d at 616. One witness testified, however, that Eugene said, “Nobody is going to stop [Defendant] until he kills somebody.” This does not fall within the Rule 803(3) state of mind exception because it is a statement of belief to prove the fact believed. Christensen, 129 Ariz. at 36, 628 P.2d at 584. Defendant did not object to this testimony, however, nor was it the subject of any pretrial motion. This claim thus is waived unless it rises to the level of fundamental error. State v. West, 176 Ariz. 432, 445, 862 P.2d 192, 205 (1993), cert. denied, 511 U.S. 1063, 114 S.Ct. 1635, 128 L.Ed.2d 358 (1994). Error is only fundamental if it goes to the essence of a case, denies the defendant a right essential to a defense, or is of such magnitude that the defendant could not have received a fair trial. State v. Cornell, 179 Ariz. 314, 329, 878 P.2d 1352, 1367 (1994). The “essence” of this case was Defendant's mental state at the time of the murders. Eugene's statement of belief does not clearly establish premeditation nor refute Defendant's defense of impulsivity. Given the clear quantum of evidence supporting premeditation, admission of this lone statement did not deprive Defendant of a fair trial. See id. at 51. We conclude that admission of Eugene's hearsay statement does not meet the “stringent standard” of fundamental error. Bible, 175 Ariz. at 573, 858 P.2d at 1176.

f. Defendant's statements

Defendant next claims that his own statements were hearsay and improperly admitted. This claim is meritless. A defendant's out-of-court statements are not hearsay when offered by the state. Ariz.R.Evid. 801(d)(2)(A); State v. Atwood, 171 Ariz. 576, 635, 832 P.2d 593, 652 (1992).

g. Other evidentiary claims

On appeal, Defendant objects for the first time to the admission of testimony revealing that Defendant had been fired from two jobs, once for fighting with a co-worker and once due to his “temperament.” Because these claims were not raised below, we review only for fundamental error. West, 176 Ariz. at 445, 862 P.2d at 204. Arguably, this testimony concerns prior bad acts inadmissible under Rule 404. The state claims Defendant made a tactical decision not to object to the testimony because it tended to show Defendant's impulsivity. We decline to resolve the issue, however, because even if the testimony was erroneously admitted, its admission does not rise to the level of fundamental error. The testimony in both instances was perfunctory and undetailed. Moreover, there was other compelling evidence of Defendant's ill temper, much of it introduced by Defendant himself on the issue of impulsivity. Defendant's final evidentiary claim concerns testimony of a witness who related a neighbor's report that Defendant had vandalized Debra's apartment. This testimony was hearsay and should not have been admitted. See Ariz.R.Evid. 801 and 802. Again, Defendant did not object to this testimony. Because other witnesses presented direct testimony on the same issue, we conclude Defendant was not prejudiced. See Fulminante, 161 Ariz. at 250, 778 P.2d at 615. We find no fundamental error.

2. Failure to instruct on manslaughter

The trial court instructed the jury on both first and second degree murder under A.R.S. §§ 13–1105(A)(1) and 13–1104. Defendant claims the trial court committed reversible error by failing to sua sponte instruct the jury on the lesser-included offense of manslaughter. We disagree. It is true that in capital cases, trial courts must instruct on all lesser-included homicide offenses supported by the evidence. State v. Comer, 165 Ariz. 413, 422, 799 P.2d 333, 342 (1990), cert. denied, 499 U.S. 943, 111 S.Ct. 1404, 113 L.Ed.2d 460 (1991). It is equally true, however, that such instructions need not be given if unsupported by the evidence. State v. Clabourne, 142 Ariz. 335, 345, 690 P.2d 54, 64 (1984).

The manslaughter statute provides, in relevant part: A. A person commits manslaughter by: 1. Recklessly causing the death of another person; or 2. Committing second degree murder ... upon a sudden quarrel or heat of passion resulting from adequate provocation by the victim; or 3. Committing second degree murder ... while being coerced to do so by the use or threatened immediate use of unlawful deadly physical force ... A.R.S. § 13–1103(A). There was no evidence to support a manslaughter instruction. These were not reckless shootings. Nor was there evidence Defendant was provoked or coerced. Defendant intentionally shot both victims at close range. The claim is meritless. See State v. Ortiz, 158 Ariz. 528, 534, 764 P.2d 13, 19 (1988).

3. Sufficiency of evidence of aggravated assault

The trial court denied Defendant's motion for directed verdicts on the aggravated assault counts. Defendant now alleges those convictions are not supported by sufficient evidence because neither police officer testified to a subjective fear of imminent physical harm. We have previously rejected this same argument. Valdez, 160 Ariz. at 11, 770 P.2d at 315. To be guilty of aggravated assault, “the defendant need only intentionally act using a deadly weapon or dangerous instrument so that the victim is placed in reasonable apprehension of imminent physical injury.” Id. Either direct or circumstantial evidence may prove the victim's apprehension. There is no requirement that the victim testify to actual fright. Id. There was ample circumstantial evidence supporting the conclusion that the officers were apprehensive or in fear of imminent harm. The police officers knew that at least one victim had been shot and that other shots had been fired. Defendant grabbed his revolver and began to aim at the officers despite their orders not to do so. Police officers, of course, are not immune from the fear that anyone would reasonably feel under these circumstances. See In re Juvenile Appeal No. J–78539–2, 143 Ariz. 254, 256, 693 P.2d 909, 911 (1984) (sufficient evidence of apprehension where police officer-victim drew gun and assumed protective stance). The jury could have concluded the officers must have acted with apprehension or fear when they used deadly force against Defendant. The evidence certainly supports that conclusion.

4. Prosecutorial misconduct

Defendant alleges the prosecutor “ran amok” at trial, particularly in his cross-examination of Dr. Allender, Defendant's psychological expert. FN9 Because defense counsel made no trial objection, again we review these claims only for fundamental error. Bible, 175 Ariz. at 601, 858 P.2d at 1204. In determining whether a prosecutor's conduct amounts to fundamental error, we focus on the probability it influenced the jury and whether the conduct denied the defendant a fair trial. See id. FN9. Defendant styles several additional alleged instances of prosecutorial misconduct as ineffective assistance of counsel claims, based on his defense counsel's failure to object. As previously noted, these claims are better left to Rule 32 proceedings. See Valdez, 160 Ariz. at 14–15, 770 P.2d at 318–19. We do not address them.

Subject to Rule 403 limitations, expert witnesses may disclose facts not otherwise admissible if they form a basis for their opinions and are of a type normally relied on by experts. Ariz.R.Evid. 703; State v. Lundstrom, 161 Ariz. 141, 145, 776 P.2d 1067, 1071 (1989). If such facts are disclosed, they are admissible only to demonstrate the basis for the expert's testimony. Lundstrom, 161 Ariz. at 146, 776 P.2d at 1071. However, to offset the potential advantage this rule bestows on the proponent of expert opinion, “it is proper to inquire into the reasons for [the] opinion, including the facts upon which it is based, and to subject the expert to a most rigid cross-examination concerning his opinion and its sources.” State v. Stabler, 162 Ariz. 370, 374, 783 P.2d 816, 820 (Ct.App.1989); Ariz.R.Evid. 705. This latitude on cross-examination extends to matters otherwise inadmissible. United States v. A & S Council Oil Co., 947 F.2d 1128, 1135 (4th Cir.1991) (“Rule 703 creates a shield by which a party may enjoy the benefit of inadmissible evidence by wrapping it in an expert's opinion; Rule 705 is the cross-examiner's sword, and, within very broad limits, he may wield it as he likes.”).

With these principles in mind, we turn to the alleged misconduct. On direct examination, defense counsel asked Dr. Allender what materials he reviewed in preparing to examine Defendant. Dr. Allender replied, in part, “a variety of police reports from the Tucson Police Department, as well as from the Las Vegas Police Department.” On cross-examination, the following exchange occurred: Q. Directing your attention, you said you had some Las Vegas police reports? A. Yes. Q. You had police reports from 1979? A. I believe I did. I would have to flip through and look for it if you want me to. Q. Do you recall in 1979 an incident when he was arrested from some criminal activity? A. I think I found a report from '79 from Las Vegas. R.T., Feb. 22, 1991, at 160–61. Defendant alleges this was improper because the trial court had ruled inadmissible Defendant's 1979 Las Vegas misdemeanor assault conviction. On cross-examination, however, the prosecutor simply asked Dr. Allender to elaborate on the reports he first mentioned on direct examination. The jury never learned the details of the conduct underlying Defendant's Las Vegas arrest. Because Dr. Allender relied on the reports in forming his opinion of Defendant, the prosecutor's cross-examination was proper.

Defendant was entitled, however, to a limiting instruction that references to the Las Vegas police reports were admissible only to show the basis of Dr. Allender's opinions. See Lundstrom, 161 Ariz. at 148, 776 P.2d at 1074. Defense counsel did not request such an instruction. On this record, we conclude that the absence of such an instruction did not deprive Defendant of a fair trial. There was no fundamental error. Defendant also argues that the prosecutor improperly cross-examined Dr. Allender about the possibility of testing Defendant to determine the validity of his claim that he had no memory of the day of the murders. The full extent of that questioning was as follows: Q. Didn't Dr. Morris [another psychologist who examined Defendant] suggest that hypnosis or amobarbital might be ideal to discover whether this defendant was malingering? A. He suggested that those might be techniques. Q. With hypnosis, you place them under hypnosis in order to find out what the truth of the matter was? A. [Answer about the theory of hypnosis and amobarbital.] Q. So you didn't, did you attempt, did you request a hypnosis evaluation? A. I didn't because I'm not as convinced about those techniques as Dr. Morris. Q. Amobarbital, is that a truth serum? A. That is what they call it, that is what people have called it along the way. R.T., Feb. 22, 1991, at 173–74.

Defendant claims this exchange prejudiced him much like questioning a defendant about refusing to take a polygraph test. It is true that, as with polygraph test results, courts generally exclude testimony induced or “refreshed” by drugs or hypnosis. Jeffers, 135 Ariz. at 431, 661 P.2d at 1132; State v. Mena, 128 Ariz. 226, 228–29, 624 P.2d 1274, 1276–77 (1981). Defendant's analogy, however, is misguided. The prosecutor's cross-examination was not intended to impugn Defendant but to test the basis and credibility of Dr. Allender's opinions concerning whether Defendant was faking his asserted memory loss at the time of the murders. Dr. Morris had examined Defendant and recommended the disputed testing. Dr. Allender relied in part on Dr. Morris's written evaluation in forming his own opinions about Defendant. Without reaching the issue of admissibility of expert testimony based upon the results of hypnotic or amobarbital examination of a subject, we conclude the prosecutor acted within the wide latitude permitted on cross-examination. Stabler, 162 Ariz. at 374, 783 P.2d at 820.

5. The Wussler instruction