TheState.Com

"Inmate to be executed today." (Associated Press Posted on Fri, Nov. 04, 2005)

Hastings Wise is scheduled to go to the death chamber today to be executed by lethal injection at 6 p.m. for killing four workers at an Aiken County plant in September 1997 as revenge for his firing several weeks earlier.

Wise, who tried to commit suicide in the plant after the shootings by drinking insecticide, has asked to die since his arrest. He refused to let his lawyers call any witnesses to ask the jury to spare his life and has brushed off any attempts to appeal since he was sent to Death Row.

“At almost every opportunity, he has expressed his wish to die,” attorney Joseph Savitz said. “Once you get someone who’s convinced they want to die, it’s difficult to change their minds.”

Wise was sentenced to death for killing four workers during a shooting rampage he planned to coincide with a shift change at the R.E Phelon plant, which makes ignition parts for lawn mowers. All four people killed either had something to do with Wise getting fired or took jobs he wanted, prosecutors said.

As he stood before the judge to have his sentence formally read after his 2001 trial, Wise said he was ready to receive his punishment. “I do not wish to take advantage of the court as far as asking for mercy. It was a fair trial. I committed these crimes,” he said in a voice so soft few in the courtroom could hear.

Wise will be the sixth person put to death in South Carolina without using all their appeals since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Wise will be the 34th inmate put to death in South Carolina since 1976

The Times and Democrat

"Hastings Wise a 'volunteer' for execution; his is scheduled this evening," by Jeffrey Collins. (Associated Press)

COLUMBIA — They are called “volunteers” — inmates who choose to give up their appeals and be put to death.

Whether they do it out of remorse, boredom or frustration the result is the same.

Hastings Wise appears to be one of them, heading to the death chamber Friday to be executed by lethal injection at 6 p.m. for killing four workers at an Aiken County plant in September 1997 as revenge for his firing several weeks earlier.

Wise, who tried to commit suicide in the plant after the shootings by drinking insecticide, has asked to die since his arrest. He refused to let his lawyers call any witnesses to ask the jury to spare his life and has brushed off any attempts to appeal since he was sent to death row.

“At almost every opportunity he has expressed his wish to die,” said attorney Joseph Savitz, who also has represented other volunteers. “Once you get someone whose convinced they want to die, it’s difficult to change their minds.”

Wise was sentenced to death for killing four workers during a shooting rampage he planned to coincide with shift change at the R.E Phelon plant, which makes ignition parts for lawnmowers. All four people killed either had something to do with Wise getting fired or took jobs he wanted, prosecutors said.

As he stood before the judge to have his sentence formally read after his 2001 trial, Wise said he was ready to receive his punishment. “I do not wish to take advantage of the court as far as asking for mercy. It was a fair trial. I committed these crimes,” he said in a voice so soft few in the courtroom could hear.

Wise will be the sixth person put to death in South Carolina without using all their appeals since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. All have died by lethal injection instead of the electric chair, and Savitz said that’s not a coincidence.

“Lethal injection has changed the dynamic of the whole thing,” Savitz said. “These guys are no longer scared to be put to death.”

Wise will be the 34th inmate put to death in South Carolina since 1976, meaning about 18 percent of the state’s executions have been volunteers. Nationwide, 117 of the 989 inmates, or nearly 12 percent, put to death since the death penalty was reinstated had appeals left, said Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center.

The numbers fluctuate from year to year. In 2004, 10 of the 59 executions were done on volunteers. In 2003, it was just four deaths out of 65, according to the center’s statistics.

Many more inmates give up for a time, but change their minds, Dieter said.

“They get discouraged, they lose, lose, lose and give up. But then after a while, they decide to go after at least one more appeal,” Dieter said.

The six volunteers in South Carolina don’t hold much in common other than giving up their appeals. Three of them were executed in 1996, shortly after the state made lethal injection an option, said Mark Plowden, a spokesman with the state attorney general’s office.

The rush of volunteers also coincided with the arrival of former Corrections Department chief Michael Moore, who moved death row from Broad River Correctional Institution in Columbia, where executions continue to be carried out, to Lieber Correctional Institution in the Lowcountry.

Moore also used the move to make conditions harsher on death row, requiring inmates to stay in their cells 23 hours a day and have minimal contact with each other even outside of their cells.

The reasons the volunteers drop their appeals varies. Wise and the most recent volunteer, Michael Passaro, planned to commit suicide after their crimes. In Passaro’s case, he jumped from his burning van, but left his 2-year-old daughter — the subject of a bitter custody battle — strapped inside.

Doyle Cecil Lucas, put to death for killing a Rock Hill couple in a robbery, told his lawyer he was filled with remorse and hoped his death brought his victims’ family relief. And Michael Torrence, executed for killing two Midlands men in a robbery, asked to drop his appeals because he couldn’t see how spending 20 or 30 more years in prison was going to benefit him.

“If I could start a euthanasia clinic in downtown Columbia, I’d have more clients than I could handle,” Savitz said. “Sometimes life is tough. I’ve witnessed lethal injection. It’s an easy way to die.”

The Augusta Chronicle

"Jurors decide death; Families, survivors express relief," by Greg Rickbaugh. (Web posted Friday, February 2, 2001)

AIKEN - Arthur Hastings Wise didn't want mercy, and he didn't get it. Twelve jurors, some of them weeping, returned a death sentence Thursday against Mr. Wise for a workplace rampage at R.E. Phelon Co. in Aiken. Four were killed and three were wounded in the attack Sept. 15, 1997.

The convicted killer closed his eyes and remained stone faced during the announcement.

``I don't have much to say except that I did not wish to take advantage of the court as far as asking mercy,'' Mr. Wise said. ``It's a fair trial. I committed the crimes.''

The verdicts brought shouts of joy from survivors of the attack and relatives of the dead. They cried and held hands in court. Outside, they gathered in groups and hugged.

``Three years, four months and 17 days,'' said Robert Wise, a former Phelon employee who is not related to the defendant, referring to his long wait for justice.

``He got what he deserved,'' said shooting victim Stan Vance, a former Phelon security guard. ``That's what I wanted to hear - death. He didn't deserve to live.''

Jurors deliberated almost five hours, and former Phelon employee Bruce Mundy worried they were considering a life sentence.

``I was sweating,'' he said. ``Life just wouldn't have been justice. I mean, he killed my friends. I believe when the time comes, he'll pay dearly.''

Janet Cooper, sister-in-law of victim Charles Griffeth, said she felt relief.

``We hated that it dragged out so long,'' she said, adding that other family members were too distraught to attend the trial.

Judge Cooper sentenced Mr. Wise, 46, to death four times for the murders of Sheryl Wood, David Moore, Leonard Filyaw and Mr. Griffeth. He also ordered 60 years in prison for the shootings of Stan Vance, Jerry Corley and John Mucha, all of whom survived. Concurrent jail time was given for burglary and possession of a gun during the commission of a violent crime.

The judge set April 3 as the execution date, but that will be delayed because Mr. Wise gets an automatic appeal to the South Carolina Supreme Court.

Defense attorneys Gregory Harlow and Carl B. Grant were crippled in their efforts to save their client from a death sentence when Mr. Wise ordered them Wednesday not to present witnesses on his behalf. The killer said he didn't want family or friends involved and didn't want to make his own plea to the jury.

Outside the courtroom, Mr. Grant said he was prepared to call Mr. Wise's family and friends and members of the North Augusta church he once attended.

``There was no question we were hampered in this case by not being able to call those 13 witnesses. In this case, the jury did not get to know that man sitting in the jail suit,'' he said.

The defense attorneys were left with only closing arguments to make a case for life.

Mr. Harlow told jurors that his client offered no excuses and no plea of insanity. He asked the jury to spare his client from death row so others could learn from him.

``What causes a person to snap like this? ... Perhaps in the future, Mr. Wise may be studied,'' Mr. Harlow said.

Taking a different approach, Mr. Grant asked jurors to use their consciences and not be swayed by the opinion of another juror. He asked if they could look themselves in the mirror or sleep at night if they voted against their consciences.

Mr. Grant argued for a life sentence, saying Mr. Wise still would die in prison. ``The only way he's going to get out is in a coffin,'' he said.

Finally, Mr. Grant asked for mercy, saying enough people had suffered already.

``In the midst of misery, you have the opportunity to choose mercy,'' he said. ``There's been enough killing. The question is when will the killing stop? When will the dying stop?''

The jury rejected the defense attorneys' arguments and agreed with 2nd Circuit Solicitor Barbara R. Morgan, who told jurors that Mr. Wise created the ``ultimate, horrible terrorist act'' and deserved the ultimate sentence.

``He didn't come to kill one or two,'' Ms. Morgan said. ``He came to maximize his hate.''

Ms. Morgan repeated the facts of the case, recalling how Mr. Wise returned to the plant after being fired. Mr. Wise had worked as a machine operator at Phelon, a company that manufactures ignitions for lawn equipment. He was fired in July 1997 after a confrontation with a supervisor.

Mr. Wise returned to the plant and shot a security guard before killing Mr. Griffeth, the human resources director who had fired him. He later walked to the tool and die area, where he fatally shot Mr. Moore and Mr. Filyaw, who worked in jobs Mr. Wise wanted.

Ms. Woods was shot three times in the quality assurance division.

Mr. Wise created terror for dozens of employees as they prepared for their shift change that day, Ms. Morgan said.

``Their innocence and safety at the workplace were shattered,'' she said. ``The facts of what happened in a small manufacturing plant in the county of Aiken demand the ultimate penalty.''

The verdicts wrapped up a two-week trial that began in Beaufort, S.C., where jury selection was held. Judge Cooper chose jurors there because of widespread publicity given the case in Aiken County.

Minutes after a jury returned four death sentences, Arthur Hastings Wise was given the chance to address the court. Here is what he said:

``Well, I've been pretty much quiet up until now. I don't have much to say except that I did not wish to take advantage of the court as far as asking mercy.

``It's a fair trial. I committed the crimes. Not once have I tried to evade my charges. As a matter of fact, from the very beginning - 40 months ago - I admitted to being at the scene of the crime, and I'm ready for my sentence.''

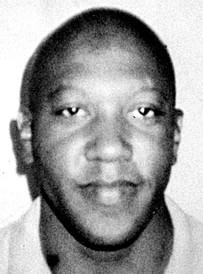

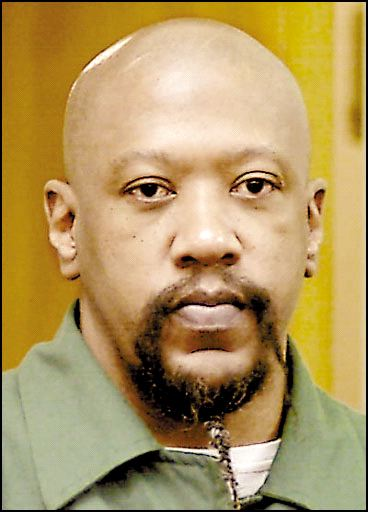

"Key players in the Wise trial," by Greg Rickbaugh. (Web posted Sunday, January 21, 2001)

The names and faces of the Arthur Hastings Wise trial

Defendant - Arthur Hastings Wise

Charged with killing four workers and injuring three others at R.E. Phelon Co. in Aiken on Sept. 15, 1997. Authorities say he had been fired from the plant two months earlier for being aggressive with a supervisor. He also had been turned down for several other positions he wanted in the plant. The North Augusta man, who stands well over 6 feet tall, spent time in prison for bank robbery and receiving stolen goods, but he earned a technical degree and found work after his release. He had worked at the Phelon plant five years before his termination.

2nd Circuit Solicitor - Barbara R. Morgan

Will argue the case to the jury, question the state's witnesses and cross-examine defense witnesses. Ms. Morgan has prosecuted five casesthat resulted in death sentences.

The victims

Sheryl Wood - Quality assurance employee

Ms. Wood was shot three times and died in the plant's rear parking lot. The 27-year-old from Bath was a 1988 graduate of Midland Valley High School, where she played basketball, volleyball and softball. She was survived by her mother and father, a brother, five sisters and her grandmother.

Charles Griffeth - Human resources director

Mr. Griffeth, 50, was the first person killed. He was in his office when he was shot twice. Mr. Griffeth, of Lexington, was responsible for firing and hiring at the company. Police say they believe he was targeted because the suspect had been fired two months before the shootings. Mr. Griffeth had worked at Phelon about six months.

Leonard Filyaw - Tool and die machinist

Mr. Filyaw, 30, was shot at his work station. The Warrenville man had been engaged for two weeks when he was killed. He was a 1985 graduate of Silver Bluff High School and liked to collect guns. He was survived by his parents, two sisters and his maternal grandparents.

David Moore - Tool and die machinist

Mr. Moore, 30, was shot twice at his work station. An Aiken resident, he had a fiancee when he was killed. He was a member of Holiness Church. He was survived by his parents, a brother and sister and his maternal grandparents.

4 killed in Aiken County shooting; suspect caught by SWAT team," by Kathy Steele. (09/16/97)

AIKEN - Leila Duncan ran for her life when she saw a gunman Monday in the hallways of R.E. Phelon Co.

``He said he would be back,'' Ms. Duncan said. ``He passed me. I saw the gun. Thank God he didn't say anything to me, because he probably would have shot me, too.''

Four people were killed and three were wounded when the shooting broke out shortly after 3 p.m., just as shifts were changing at the plant. Three of the bodies were found in the tool and die and human resources departments. A fourth victim was found in the rear parking lot.

``One of those shots could possibly have been for me,'' the assembly worker said. ``I just ran for my life when I heard the shots. People were running as fast as they could, yelling `Get out! Get out!'''

The accused gunman, Arthur Hastings Wise, 43, of North Augusta, was listed in critical condition at Aiken Regional Medical Centers late Monday after ingesting an unknown substance, possibly a drug.

Mr. Wise had been fired from the plant within the last few weeks, plant employees said.

Aiken County Coroner Sue Townsend identified the victims as David Moore, 30, of North Augusta; Esther Sheryl Wood, 27, of Bath; Charles Griffith, 50, of Columbia; and Ernest L. Filyaw, 31, of Warrenville. Ms. Wood's body was found in the parking lot, Ms. Townsend said.

The killings came almost exactly one year after Mark David Hill opened fire in the South Carolina Department of Social Services office in North Augusta, leaving three people dead.

``I thought, `My God! We did this same thing last year,''' Mrs. Townsend said.

Lt. Stan Vance, a 49-year-old security guard from Jackson, and John Mucha, 60, of Aiken, were listed in serious condition at Aiken Regional with gunshot wounds. Lucius Corley, 44, of Graniteville, was treated and released, authorities said.

Five other employees were treated and released with minor injuries, hospital officials said.

Police were releasing only sketchy details late Monday as they worked to piece together the sequence of events. The 911 emergency call came in at 3:07 p.m. to the Aiken County Sheriff's Office.

Within minutes, an army of law enforcement officers responded from the sheriff's office, the State Law Enforcement Division, the FBI, the Aiken and North Augusta public safety departments, Aiken County Emergency Medical Services and the Edgefield County Sheriff's Department.

Helicopters hovered overhead at the plant and state agents brought in an armored car.

Employees at Phelon, which manufactures ignition systems and flywheels for lawn equipment, said they could have predicted the shooting spree.

Margaret Drafts, who works in the plant's payroll department, said she had spoken with Mr. Wise frequently on the phone about payroll deductions.

``He had applied for several different positions in tool and die and quality assurance departments and he didn't get them,'' she said. ``I never thought he would have done that. He was always pleasant to me.''

``When he was fired, he said this wasn't the end of it. Nobody paid it any attention,'' Angela Humphries said.

Others heard the same thing. ``He told them it wasn't over. He'd be back,'' Lisa Beck said.

Lt. Michael Frank, spokesman for the sheriff's office, confirmed that Mr. Wise was a former employee of Phelon. He wasn't aware of how long he had worked at the plant or the reasons for his dismissal.

``We were told an individual showed up at the plant, walked inside and began shooting,'' Lt. Frank said. ``We don't have information on whether it was a random shooting or if he had targets.''

The gunman drove to the plant, parked his red two-door Saturn and pointed a weapon at Lt. Vance, the sheriff's spokesman said. He shot and wounded the guard and headed for the main door.

Mr. Wise cut the telephone lines before entering the building, Ms. Duncan said.

Eyewitnesses said they fled the plant, scrambling for doors as other workers and supervisors came through shouting, ``There's a man with a gun.''

Two people were shot to death in the plant's tool and die area, one in the human resources department and one in the back parking lot, Lt. Frank said.

Carol Woody said she was walking toward the personnel office when Mr. Wise ran by.

``He pushed me out of the way,'' Ms. Woody said. ``He went in the human resources door. A gun was in his left hand. I could see the gun. I know the gun was black. He's a big man.''

A lot of employees said they felt lucky to get out alive. Bruce Mundy, who works in the flywheel department, was standing next to a woman who was shot.

``He killed everybody,'' Mr. Mundy said as his mother held tightly to his arm. They were standing outside the Golden Pantry, milling around with a couple of hundred other employees and relatives looking for their loved ones after the shooting.

Vernelle Weaver heaved a sigh of relief when she found her husband, Jimmy, outside and safe.

``When I came up I didn't see him,'' she said. ``All kinds of things were going on in my head.''

Danny Goldston said the man next to him was shot.

``I didn't know the guy,'' he said. ``I heard popping sounds. I seen a flash from a pistol. Then I left.''

With most of the employees evacuated after the shooting, Lt. Frank said the sheriff's entry team and state agents' SWAT team began searching each section of the building for Mr. Wise.

As the search proceeded, two men and a woman were hiding under desks on the first floor, communicating with a 911 dispatcher by portable telephone. They were found and evacuated.

SLED Chief Robert Stewart said Mr. Wise was found on the second floor near the quality assurance office. The weapon, a handgun, was discovered nearby.

``He said nothing,'' Chief Stewart said. ``He was lying on the floor and there appeared to be something physically wrong with him.''

Wikipedia

Hastings Arthur Wise

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Hastings Arthur Wise (February 16, 1954 – November 4, 2005), was a convicted U.S serial killer who was executed in the U.S. state of South Carolina for killing four former co-workers. Sometimes erroneously referred to by the press as "Arthur Hastings Wise," he was known simply as Hastings Wise to the people he worked with.

Wise shot and killed Charles Griffeth, David Moore, Leonard Filyaw, and Sheryl Wood on September 15, 1997 at the R.E. Phelon Company lawn mower parts manufacturing factory in Aiken, South Carolina, his former employer.

Crime

Hastings Wise was an ex-convict who had served prison time for bank robbery and receipt of stolen goods before obtaining a technical degree and, eventually, finding employment at R.E. Phelon. He had no criminal convictions for the approximately fifteen years between his release from prison and the murders of 1997. According to his pastor, in eleven years, he had "hardly ever" missed a week of Sunday services.

The motive for the murders was Wise's termination of employment with the factory following a confrontation with a supervisor eleven weeks earlier. Wise had worked there as a machine operator for more than four years until his firing in July 1997. After his dismissal, Wise told co-workers he would "be back."

Testimony was presented at trial that he had felt discriminated against for his African-American race all his life. The jobs he wanted were given to white employees by a white personnel director. Wise killed the director, and three other white workers as well, some (possibly all) of whom had jobs he had been denied.

On September 15, the day of the murders, Hastings Wise drove into the Phelon employee parking lot for a scheduled meeting to pick up a box of personal items from Stanley Vance, a security guard. Instead, he shot Vance in the chest with a semi-automatic pistol. Wise tore out the guard station's phone lines and told Vance, "I got things to do." Vance survived his injuries.

Wise then entered the main building, first going to the personnel office, where he fatally shot Charles Griffeth, the man who had fired him, twice in the back. Griffeth was 56 years old.

The next victims were in the tool and die area. He fired rapidly, killing David Wayne Moore, 30, and Ernest Leonard Filyaw ("Leonard"), 31. Two other people were injured in this area. According to news reports, both Moore and Filyaw were engaged to be married at the time of their murders. According to court documents, Wise had wanted a promotion to the tool and die area where Moore and Filyaw worked, but had not gotten it.

The last victim was Esther Sheryl Wood ("Sheryl"), 27, who held a quality control position. He first shot her in the back and leg and then, in what Aiken County prosecutor Barbara Morgan described as "execution-style," shot her in the head. Contemporary news reports stated he had been denied a promotion to Wood's job.

Wise reloaded several times as he walked through the plant, shooting and screaming something incomprehensible to the witnesses who later testified at trial. Police recovered four empty magazines, each with a capacity of 8 bullets. There were also four full magazines and 123 more bullets.

After Wise reached the upper floor of the plant, he lay down and swallowed insecticide as a suicide attempt. He was semi-conscious when police located him.

Trial and appeals

Wise was indicted in August 1998. His trial was delayed when the judge assigned to it was changed in 2000, and underwent a further delay when one of his defense attorneys was arrested in North Augusta, South Carolina on domestic violence charges. Although the crimes were committed in Aiken County, the trial itself was held in Beaufort County, South Carolina by order of the trial judge, who felt that the publicity around the crime may have tainted the Aiken County jury pool.

A psychiatrist who assessed Wise said that he drove over 9,000 miles in the two weeks before the murders, in a desire to visit and see sights such as the San Diego Zoo before carrying out the crimes he planned to commit. The psychiatrist said that the only motive behind the murders was the dismissal from his job, and that Wise felt he had been mistreated all his life due to being African American.

After a two-week trial in which the defense called no witnesses, Wise was convicted of the four murders after five hours of deliberation by the jury.

During the sentencing phase of the trial, at Wise's insistence, no character witnesses were called by the defense, although his attorneys had a slate of thirteen people willing to testify. Wise reportedly said:

"I don't have much to say except that I did not wish to take advantage of the court as far as asking [for] mercy. It's a fair trial. I committed the crimes."

He was given the death penalty for all four murders. Wise was also sentenced to 60 years for the non-fatal shootings Stan Vance, Jerry Corley and John Mucha, all of whom survived. Shorter concurrent sentences were given for burglary and possession of a gun during the commission of a violent crime.

After conviction, on February 2, 2001, Wise was transferred to the custody of the South Carolina Department of Corrections, where he was known as Inmate #00005074.

After an automatic appeal to the South Carolina Supreme Court, the conviction and sentence were upheld. Wise's court-appointed attorneys then appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which declined to hear the appeal.

At that point, Wise wrote to the state Supreme Court to say that the second appeal was made against his wishes and that he wanted to die. Wise thus waived the right to further appeals of his death sentence. He was the sixth person to do so since South Carolina reintroduced capital punishment after the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Gregg v. Georgia.

By refusing to pursue all his permitted appeals, Wise became what is known in legal and correctional circles as a "volunteer" for execution. This is consistent with his careful planning and the suicide attempt at the plant, which suggest that he may have been planning "suicide by cop" as well. Whether by the insecticide he ingested, or by police action, or by formal execution, Hastings Wise clearly did not intend to survive his revenge spree.

After hearings to assess his competence to make this decision, the execution date of November 4 was set by the state Supreme Court on September 26, 2005.

Execution

Wise was executed by lethal injection at the Broad River Correctional Institution on Friday, November 4, 2005. He chose to make no final statement but did order a last meal of lobster back, french fries, coleslaw, banana pudding and milk. During the execution process, he just stared at the ceiling. He was pronounced dead at 6:18 p.m. EST.

Wise was the second person executed in South Carolina in 2005 and the thirty-fourth inmate executed there since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976. According to a roster maintained by the prosecutor of Clark County, Indiana, Wise was the 992nd person to be executed nationwide since the restoration of the death penalty in 1976.

Civil suits

Ten people who were survivors of the shooting, or relatives of the dead, filed a civil suit against the security firm for which Vance worked, Regent Security Services. Federal District Court Judge Cameron Currie oversaw the settlement which was reached Monday, November 5, 2001, just one day before the case was scheduled to go to trial. The amount of the settlement was not disclosed.

Vance himself sued R.E. Phelon, and settled with them in March 2001 prior to the Regent Security Services settlement. Vance's argument was that Phelon failed to warn him that Hastings Wise had a history of prior disruptions there. The amount of Vance's settlement was also undisclosed.

Phelon and its insuror, Liberty Mutual, brought four suits against Regent on behalf of 32 employees who received workers' compensation payments for injuries and trauma related to the event. In July 2001, Phelon and Liberty dropped the four state lawsuits and intervened in the federal lawsuits filed by the victims, hoping to recover some of the over $380,000 spent on the work comp claims.

Pro Death Penalty.com

The state Supreme Court has set an execution date for a man convicted of killing four former co-workers at an Aiken County plant in 1997. The justices have set a November 4th execution date for 51-year-old Arthur Hastings Wise. Wise had asked to have his appeals dropped almost immediately after his 2001 conviction. The attorney general's office says Wise had offered no defense during his trial. Wise was within weeks of dying by lethal injection in June 2004 when the state Supreme Court stopped his execution because his lawyer said he wanted to appeal and Wise wrote a letter to the court saying he wanted to die. Charles Griffeth, David Moore, Earnest Filyaw and Cheryl Wood died and three other people were hurt in the attack at the R.E. Phelon lawnmower ignition plant.

UPDATE: Charles Griffeth was hired by R.E. Phelon to fill the management opening in human resources. Pam Morey, his assistant, said. "(Mr. Phelon) got the best man for the job when he hired Charles. Charles would walk through the plant and talk and joke with the workers. He treated people with tenderness. He made it worthwhile going to work." But the good times ended violently Sept. 15 that year, when Hastings Arthur Wise, a former Phelon machine operator who had been fired two months earlier, returned with a gun, nearly 200 rounds of ammunition and a plan to make those he felt had wronged him pay in blood. At the end of the rampage, four were dead and three wounded.

The violence started at about 3 p.m. on that Monday eight years ago when security officer Stanley Vance took the first bullet from Wise's gun - in the chest at close range - and fell in the guard shack where he had been on duty. From there, Wise headed for the human resources department inside the main building. Pam Morey, whose last name at the time was Holley, was on the telephone at her desk in the outer office when Wise rushed in, searching for Charles Griffeth. "I saw the shadow just dart past me. I froze when I heard the noise (of gunfire)," she said. Charles Griffeth had also been on the phone when Wise entered. He tried to take cover when he spotted the gun, said his sister-in-law Janet Cooper. But there was no time to find safety. The well-loved manager died at his desk when he was shot twice in the back.

Returning to the outer office, Wise accosted Pam Morey. "He put the gun between my eyes," she said. He then ordered her off the phone and yanked it out of the wall. "I just started pleading and praying. I said, 'I have kids. I'm a single mother. Please don't kill me,'" Mrs. Morey said. The gunman was distracted by someone who entered the building, and he left the room. Terrified, Mrs. Morey said she hid under her desk "because I didn't want to see somebody get shot." When she eventually heard shots farther off, she jumped up and ran from the building. Wise continued his rampage, firing and reloading. He moved to the tool and dye area where he had wanted to work but had been denied. There, David Moore, Earnest Filyaw, Lucius Corley and John Mitchell were shot. David Moore and Earnest Filyaw both died.

After a frantic search, worker John Goad discovered his brother behind a work station and figured he was hiding from the gunman. Then he rolled his brother over. "I could see the blood on his chest. His eyes were still open. He was starting to turn purple," Mr. Goad told the jury in Wise's trial as tears streamed down his face. ``When I realized he was gone, I just started calling his name. I said, 'No, David, no!'" David Moore, his brother and co-worker, was gone. But the war-like atmosphere around Mr. Goad continued. "I could hear the shots, and I could hear people screaming,'' he said. "I knew I had to go. I knew I couldn't carry him out. So I ran out the way I came." An Aiken resident, Moore had a fiancee when he was killed. He was a member of Holiness Church. He was survived by his parents, a brother and sister and his maternal grandparents.

After the gunman walked out of the tool and die area toward the quality assurance division, employee David Langille said, Mr. Langille checked on co-worker Leonard Filyaw, who had been hit once with gunfire. "His eyes, there was a blank stare. I knew he was dead,'' Mr. Langille said. David Moore had the same lifeless stare, he said. But John Mucha was alive, begging and pleading for help for his gunshot wound. His co-workers came to his aid and carried him outside. Earnest Filyaw was from Warrenville and had been engaged for two weeks when he was killed. He was a 1985 graduate of Silver Bluff High School and liked to collect guns. He was survived by his parents, two sisters and his maternal grandparents.

After hearing gunfire from the shootings of Moore and Filyaw, other employees ran. Sheryl Wood almost made it out, but that wasn't Wise's plan. He shot the young woman who got the job he wanted. She fell, with bullets in her back and leg. The gunman walked up to where she lay on the floor and shot her in the head. In the quality assurance office, she lay there, pleading with others not to leave her. Minutes later, die cast worker Bruce Mundy appeared. He had been outside but decided to return and help the wounded. He soon discovered Ms. Wood. "I yelled into the radio that I had found somebody and they were hurt,'' Mr. Mundy told the jury, fighting back tears. "I couldn't move her. She squeezed my hand, but as far as talking - no, she couldn't talk. ... She was gurgling, her eyes rolled back into her head, and she died.'' Still, Mr. Mundy and others lifted Ms. Wood onto a stretcher and carried her outside, just in time to meet arriving police and rescue personnel. Sheryl Wood was the last of seven victims. The 27-year-old from Bath was a 1988 graduate of Midland Valley High School, where she played basketball, volleyball and softball. She was survived by her mother and father, a brother, five sisters and her grandmother. Only Mr. Vance, Mr. Corley and Mr. Mitchell survived.

Aiken Public Safety Officer Bob Besley testified that he arrived at the plant and eventually found the body of human resources manager Charles Griffeth in the front office, a telephone still in his hand. The manager's eyes were fixed and dilated, and he had no pulse, Officer Besley said. Beth Griffeth, Charles Griffeth's widow, was too traumatized to attend any of the trial and will be out of the state, said her sister Mrs. Cooper. "She didn't want to face it," Mrs. Cooper said. "We're just so hoping that once this is over, it will give her some closure. She won't have to deal with it every time something else comes up." Pam Morey understands her pain. "She lost one of the best men God ever made. I felt like I lost my dad when I lost him," she said.

UPDATE: Hastings Wise was put to death by lethal injection Friday night for killing four workers at an Aiken County plant in September 1997 out of revenge for being fired. Wise, 51, tried to die the day of the killings, drinking insecticide after the plant emptied. But it only made him violently ill. Wise refused to let witnesses testify for him as jurors chose between the death penalty and life in prison, then refused to appeal his conviction. Prosecutors said Wise waited for afternoon shift change at the R.E. Phelon lawnmower ignition plant so he could make sure all of his targets were there. He only shot people who he thought led to his firing several weeks before or took jobs he wanted, authorities said. Wise made no final statement and never looked at the victims' families or other witnesses. Instead, he stared at the ceiling and took several deep breaths as the lethal mix of three chemicals went into his veins. His rapid blinking ended with his eyes wide open at about the same time his chest stopped rising. It was about two minutes after the curtain to the death chamber opened. The official time of death was 6:18 p.m.

"He didn't die a violent death. He died easy, went to sleep," said Tommy Thompson. Thompson's son David Moore was one of the four killed eight years ago. He wanted to be there to watch justice be served. "He's dead. He won't be able to commit crimes again, but you never get over the loss," said Thompson. According to witnesses, Wise didn't look at anyone nor did he offer any words to the victims' families. "I was hoping he might have said, I'm sorry, but it just wasn't in him," said John Wood, whose daughter Sheryl was killed in the attack. Zach Bush was working at R.E. Phelon that fateful day, but Wise spared his life. He came to honor those who weren't as fortunate. "All of our family there at the R.E. Phelon company hope this will be a passing page in the chapter of the book of our lives," said Bush. "When it happens to you and your family, that's when it comes home and no one should ever have to go through that," said Thompson. And though the execution brings closure, victims say they'll never forget the loss.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Arthur Hastings Wise - South Carolina - November 4, 2005

Arthur Hastings Wise, a white man, is scheduled to be executed on Nov. 4, 2005 for the Sept. 15, 1997 shooting deaths of Charles Griffeth, David W. Moore, Earnest L. Filyaw, and Cheryl Wood in Greenville County. Wise returned to work after being fired from his job as a machine operator and shot the four victims in addition to injuring many others. Wise tried to kill himself after the murders by swallowing insecticide; however he was taken to the hospital after being arrested and survived.

Wise has shown sorrow and a desire to pay the price for his actions. He has dropped his appeals and is “volunteering” to be executed. At the time of the crime there was evidence of LSD in Wise’s system.

It is not the job of the state to assist its citizens in suicide. Yet that is exactly what the state of South Carolina would be doing if Wise is executed. Wise is clearly a troubled man and clearly the death penalty is an inappropriate sentence.

Please write Gov. Mark Sanford requesting that he commute Wise’s sentence to life in prison.

State v. Wise, 359 S.C. 14, 596 S.E.2d 475 (S.C. 2004) (Direct Appeal).

Background: Defendant was convicted in the Circuit Court, Aiken County, Thomas W. Cooper, Jr., J., of four counts of murder, for which sentence of death was entered for each count, three counts of assault and battery with intent to kill, one count of second-degree burglary, and four counts of possession of a weapon during the commission of a violent crime. Defendant appealed.

Holdings: The Supreme Court, Burnett, J., held that:

(1) trial judge did not abuse his discretion by excusing prospective juror for cause during individual voir dire after juror stated that she could not under any circumstances find defendant guilty;

(2) trial court did not abuse its discretion during penalty phase by refusing to allow a surviving victim to testify on cross-examination that he did not personally believe defendant should receive the death penalty; and

(3) sentence of death imposed on defendant for each of his four convictions of murder was neither excessive nor disproportionate in light of crime and defendant.

Affirmed.

Justice BURNETT:

Hastings Arthur Wise (Appellant) was convicted of four counts of murder, three counts of assault and battery with intent to kill, one count of second-degree burglary, and four counts of possession of a weapon during the commission of a violent crime. The jury found two aggravating circumstances: a murder was committed during the commission of a burglary; and two or more persons were murdered by one act or pursuant to one scheme or course of conduct. See S.C.Code Ann. § 16-3-20(C) (2003 and Supp.2003).

Appellant was sentenced to death on the jury's recommendation for each count of murder, twenty years consecutive on each count of assault and battery with intent to kill, fifteen years concurrent for burglary, and five years concurrent on each weapon possession conviction. This appeal follows.

FACTS

Appellant drove into the employees' parking lot at the R.E. Phelon manufacturing plant in Aiken County at about 3 p.m. on September 15, 1997, as the work shifts were changing. He had been fired from his job as a machine operator at the plant several weeks earlier. Appellant did not present a defense. His lawyers' examination of some plant employees during the trial indicated Appellant may have been upset because he had not received a promotion from machine operator to the tool and dye division.

Stanley Vance, the security officer on duty, testified he believed Appellant had come to pick up his personal belongings which were stored in the guard station. Appellant exited his vehicle, walked to the guard station, and shot Vance once in the upper abdomen with a semi-automatic pistol.

During the guilt phase of the trial, in addition to two security officers, the State presented fifteen employees as witnesses to the shootings at the plant. All identified Appellant as the perpetrator. Their testimony, along with the testimony of law enforcement investigators and the medical examiner, established the following events:

After tearing out telephone lines in the guard station, Appellant entered the plant's human resources office. He shot personnel manager Charles Griffeth, age 56, twice in the back, killing him as he sat at his desk. Appellant held his pistol to the head of a secretary as he exited Griffeth's office, tore out the secretary's telephone line, and continued into the plant.

Appellant walked to the tool and dye area where several employees were working. He fired his pistol repeatedly at the employees, killing David W. Moore, age 30, and Earnest L. Filyaw, age 31. Lucius Corley and John Mitchell were wounded. Mitchell was shot in the chest, and suffered extensive and severe internal injuries which required multiple surgical procedures.

Appellant walked toward another area of the plant as employees, who gradually had become aware of the shootings in the plant, fled the building. He shot Cheryl Wood, age 27, in the back and leg as she stood near a doorway. She was fatally shot after she fell to the floor, described by the prosecutor as an execution-style slaying.

Appellant continued firing his pistol at other employees in other areas of the plant. Witnesses observed Appellant reload his pistol several times as he progressed through the plant. Investigators recovered four empty, eight-round magazines at the scene, plus four full magazines and 123 additional rounds in Appellant's possession. Some witnesses related Appellant was "screaming something" unintelligible during the shootings.

Appellant walked to an upstairs office, shooting through glass windows and doors. He entered an office, lay down on the floor, and swallowed or attempted to swallow an insecticide. Police found Appellant lying there semi-conscious, arrested him, and transported him to a hospital.

The trial judge ruled Appellant competent to stand trial. Appellant did not present witnesses or evidence during the guilt or sentencing phases of the trial. He refused before trial to identify for his attorneys family or friends as favorable witnesses. During the sentencing phase, Appellant refused to allow his attorneys to call thirteen mitigation witnesses to present evidence that life imprisonment without parole was the appropriate sentence.

Appellant's refusal prompted the trial judge to again have Appellant examined during the trial by a psychiatrist, who again testified Appellant was competent. Although his attorneys had evidence of the presence of the hallucinogenic drug LSD in his body when the shootings occurred, Appellant told the judge "I was in total control of my faculties at the time."

ISSUES

I. Did the trial judge err in excusing a potential juror for cause during individual voir dire without allowing defense counsel to examine her about personal religious beliefs that would preclude her from finding Appellant guilty of the crimes charged?

II. Did the trial judge err in refusing to allow a surviving victim, called by the State to provide victim-impact evidence, to testify on cross-examination that he previously had stated Appellant should not receive the death penalty?

DISCUSSION

I. Individual voir dire issue

Appellant argues the trial judge erred in excusing a potential juror (Juror) for cause during individual voir dire without first permitting his lawyers to personally examine her. Appellant contends the judge did not have the discretion to excuse Juror. We disagree.

Juror was the fourth venireman examined during individual voir dire. Responding to questions from the trial judge, Juror testified she would accept and apply the law as instructed by the court. She testified she could find a defendant not guilty in a criminal case; however, she could not find a defendant guilty. Juror testified she was a member of the "Holiness" religion, did not believe in judging anyone, and would be unable under any circumstances to find a defendant guilty. Juror testified, "I mean, they could be guilty but I'm not going to sit on the jury stand and say that they're guilty because it's not right to say whether they're guilty or not."

The judge and attorneys discussed Juror's responses outside her presence. The judge requested Appellant's attorneys suggest questions he might ask Juror. No questions were suggested, but Appellant's attorneys requested an opportunity to examine and possibly rehabilitate Juror by clarifying her responses. The judge denied the request, but examined her further about the source of her beliefs. Juror testified her beliefs were personal, and she was unaware of any pastoral counseling or similar program she could undergo in order to sit in judgment of another person. Juror testified she could not find someone guilty in "so serious as this case is" and she did not "want to have [any] part in saying what, you know, where he's going to be at, you know."

The judge excused Juror for cause over defense counsel's objection, relying primarily on State v. Tucker, 334 S.C. 1, 512 S.E.2d 99 (1999). "The presiding judge shall determine whether any juror is disqualified or exempted by law and only he shall disqualify or excuse any juror as may be provided by law." S.C.Code Ann. § 14-7-1010 (Supp.2003). The authority and responsibility of the trial court is to focus the scope of the voir dire examination as set forth in S.C.Code Ann. 14-7-1020 (Supp.2003). State v. Hill, 331 S.C. 94, 103, 501 S.E.2d 122, 127 (1998) (citing State v. Plath, 281 S.C. 1, 313 S.E.2d 619 (1984)). A capital defendant has the right to examine jurors through counsel pursuant to S.C.Code Ann. 16-3-20(D) (Supp.2003), but that statute does not enlarge the scope of voir dire permitted under Section 14-7-1020. [FN2] Id. The scope of voir dire and the manner in which it is conducted generally are left to the sound discretion of the trial judge. Id. (citing State v. Smart, 278 S.C. 515, 299 S.E.2d 686 (1982), overruled on other grounds by State v. Torrence, 305 S.C. 45, 406 S.E.2d 315 (1991)).

FN2. Section 14-7-1020 provides:

The court shall, on motion of either party in the suit, examine on oath any person who is called as a juror to know whether he is related to either party, has any interest in the cause, has expressed or formed any opinion, or is sensible of any bias or prejudice therein, and the party objecting to the juror may introduce any other competent evidence in support of the objection. If it appears to the court that the juror is not indifferent in the cause, he must be placed aside as to the trial of that cause and another must be called.

Section 16-3-20(D) provides:

Notwithstanding the provisions of Section 14-7-1020, in cases involving capital punishment a person called as a juror must be examined by the attorney for the defense.

"Voir dire examination serves the dual purposes of enabling the court to select an impartial jury and assisting counsel in exercising peremptory challenges." Mu'Min v. Virginia, 500 U.S. 415, 431, 111 S.Ct. 1899, 1908, 114 L.Ed.2d 493, 509 (1991). A capital defendants right to voir dire, while grounded in statutory law, also is rooted in the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. See id.; Morgan v. Illinois, 504 U.S. 719, 729, 112 S.Ct. 2222, 2230, 119 L.Ed.2d 492, 503 (1992). To be constitutionally compelled, it is not enough that a question may be helpful. Rather, the trial court's failure to ask or allow a question must render the defendant's trial fundamentally unfair. Mu'Min, 500 U.S. at 425, 111 S.Ct. at 1905, 114 L.Ed.2d at 506; State v. Tucker, 334 S.C. 1, 10, 512 S.E.2d 99, 103 (1999).

An appellate court will not disturb the trial court's disqualification of a prospective juror when there is a reasonable basis from which the trial court could have concluded the juror would not have been able to faithfully discharge his responsibilities as a juror under the law. Tucker, 334 S.C. at 11, 512 S.E.2d at 104 (citing State v. Green, 301 S.C. 347, 392 S.E.2d 157 (1990)).

We conclude the trial judge properly excused Juror for cause. Section 14-7-1010 requires the judge determine whether a juror is disqualified or exempted by law, a determination that may be made before parties are given an opportunity to examine the juror in a death penalty case. A juror who testifies she would not be able to find a criminal defendant guilty under any circumstances is disqualified by law. Such a person may not be seated because she would be unable to fulfill her duties as a juror or apply the law as it is given to her by the court. See also State v. Plath, 281 S.C. 1, 5, 313 S.E.2d 619, 621 (1984) (court repeatedly has said test of juror's qualification under Section 16-3-20 is ability to both reach a verdict of either guilt or innocence and, if necessary, to vote for death sentence).

In addition, the trial judge's excusal of Juror is supported by Tucker, supra. In that case, the trial court excused for cause a juror, a Jehovah's Witness, because the juror stated he could not sit in judgment without undergoing religious counseling that might take four days. The juror was excused during the general qualifying of the jury pool. We rejected the argument that the excusal improperly prevented defense counsel from rehabilitating the juror during individual voir dire as to his views on the death penalty and the special circumstances which might allow him to sit as a juror. We found the trial court properly excluded the juror because his religious beliefs which prohibit judging another person would prevent or substantially impair the performance of juror's duties; therefore, a reasonable basis existed in support of the trial court's excusal of the juror for cause. Tucker, 334 S.C. at 10-11, 512 S.E.2d at 103-104.

In the present case, the trial judge's lengthy colloquy with Juror revealed she would be unable to return a verdict of guilty under any circumstances. Her belief she should not sit in judgment of another rendered her incapable of fulfilling her basic responsibilities as a juror, and would have prevented or substantially impaired the performance of her duties as a juror. Consequently, a reasonable basis existed for the trial judge's excusal for cause of Juror. See Sections 14-7-1010 and -1020; Tucker, supra; Plath, supra. Furthermore, we conclude her excusal for cause did not render Appellant's trial fundamentally unfair. See Mu'Min, supra; Tucker, supra.

Appellant argues we should find State v. Atkins, 293 S.C. 294, 360 S.E.2d 302 (1987), overruled on other grounds by Torrence, supra, to be controlling, not Tucker. In Atkins, the trial court excused four potential jurors for cause, without allowing counsel for either side to examine them, after concluding they were opposed to the death penalty.

We emphasized in Atkins that case law and the mandatory language of Section 16-3-20(D) "make it clear that the trial courts discretion does not extend so far as to authorize it to refuse counsel the right to conduct any examination at all in a capital case. When our legislature has seen fit to enact special statutory requirements to be followed in death penalty cases, the courts should endeavor to see that these are strictly followed." Atkins, 293 S.C. at 297, 360 S.E.2d at 304.

We explained in Atkins that further examination by counsel might reveal the juror would be able to subordinate his personal views and apply the law of the state. The error could not be deemed harmless as the defendant was sentenced to death; therefore, we reversed and remanded for a new penalty phase proceeding. Id; see also State v. Owens, 277 S.C. 189, 192, 284 S.E.2d 584, 586 (1981) (finding error in trial courts dismissal of two potential jurors for cause, without allowing defense counsel to examine them, when jurors indicated opposition to death penalty, although issue was moot because defendant was given a life sentence).

Atkins is distinguishable on two grounds. First, the juror qualification issue in Atkins was the ability of jurors to consider both the death penalty and life imprisonment. In the present case, the qualification issue was whether Juror believed she could sit on a jury in judgment of another person at all. Her comments and belief she could never find someone guilty in such a serious case disqualified her, at a more fundamental level than the jurors in Atkins, to serve. See Plath, supra.

Second, it is clear from this record that further examination of Juror would have been unlikely to reveal she could subordinate her views and apply the law of the state. Juror unequivocally and repeatedly stated during thorough examination by the trial judge she would be unable to find the defendant guilty. In fact, Appellant's attorneys were given an opportunity to suggest additional questions to the trial judge, but suggested none. Nevertheless, the trial judge after conferring with counsel examined Juror further to ascertain the basis of her beliefs.

Appellant also contends Tucker is distinguishable because Juror was excused during individual voir dire, while the juror in Tucker was excused during the general juror qualification process. This distinction is unpersuasive because the basic requirement of ensuring a juror is qualified and able to render a fair and just verdict to either party based on the facts and the law applies throughout the jury selection process.

We do not intend, by this decision or the decision in Tucker, to dilute the mandate of Section 16-3-20(D) as expressed in Atkins, supra. When the record reveals a juror plainly is not qualified, after thorough examination by the trial judge, to serve and it does not reasonably appear further examination would likely reveal the juror could subordinate his views and apply the law of the state, a reasonable basis exists for excusal for cause of the juror without further examination by defense counsel. Accordingly, the trial judge did not err and properly exercised his discretion in excusing Juror for cause.

II. Cross-examination of victim impact witness

Appellant contends the trial judge erred by refusing to allow a surviving victim to testify on cross-examination during the sentencing phase of the trial that he did not personally believe appellant should receive the death penalty. We disagree.

Security officer Vance testified during both the guilt and sentencing phases of the trial. Vance was shot once in the upper abdomen by Appellant, resulting in temporary paralysis in his legs, rendering him totally disabled, unable to work. Vance testified he suffers constant, intense pain requiring daily medications. He has weekly psychiatric appointments and has been diagnosed with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Vance testified he knew Appellant only by sight and had little or no interaction with him on the job.

During cross-examination in the sentencing phase, Appellant's attorney attempted to question Vance about a statement he made to a newspaper reporter shortly after the shootings, in which Vance reportedly said Appellant should not receive the death penalty. The trial judge sustained the State's objection and did not allow the testimony.The judge earlier had refused to allow Appellant to question Vance about the same alleged statement to the media during the guilt phase, as it was irrelevant. This ruling obviously was proper. Appellant now challenges only the ruling during the penalty phase.

A capital defendant is prohibited from directly eliciting the opinion of family members or other penalty-phase witnesses about the appropriate penalty. Such questions go to the ultimate issue to be decided by the jury-- life in prison versus the death penalty--and are properly reserved for determination by the jury. State v. Matthews, 296 S.C. 379, 393, 373 S.E.2d 587, 595 (1988) (affirming exclusion of family members' opinion about appropriate penalty and what effect the death penalty would have on them, although defendant could show no prejudice because his mother expressed her opinion to jury despite judge's ruling); State v. Adams, 277 S.C. 115, 283 S.E.2d 582 (1981) (whether death penalty should be imposed is an ultimate issue reserved for jurys determination), overruled on other grounds by Torrence, supra.

Similarly, a capital defendant may not present a penalty-phase witness to testify explicitly what verdict the jury "ought" to reach. Torrence, 305 S.C. at 51, 406 S.E.2d at 319. A capital defendant may not present witnesses merely to testify of their religious or philosophical attitudes about the death penalty. Id.

[17] [18] On the other hand, a capital defendant may present witnesses who know and care for him, and who are willing on that basis to plead with the jury for mercy on his behalf. Thus, a close relative of a defendant, such as his mother, may make a general plea for mercy for the life of her son. Torrence, 305 S.C. at 51, 406 S.E.2d at 319. A close relative of a defendant, such as his sister, may be asked whether she wants the defendant to die, which is akin to asking her to make a general plea for mercy and not explicitly directed toward eliciting her opinion of what verdict the jury should reach. State v. Johnson, 338 S.C. 114, 125-127, 525 S.E.2d 519, 524-525 (2000) (while trial court erred in limiting sister's testimony, defendant was not prejudiced because sister was able to make a general plea for mercy on his behalf and clearly expressed her love and affection for him).

We are unpersuaded by Appellant's argument he should have been allowed to cross-examine Vance pursuant to Torrence and Johnson. We accept as true the proffer by Appellant's attorney Vance would testify he told the media shortly after the shootings he did not personally believe Appellant should receive the death penalty. However, such a statement by Vance would not constitute a plea for mercy on behalf of Appellant. Instead, it would constitute Vance's opinion of what verdict--life in prison versus the death penalty--the jury should reach. Accordingly, the trial judge properly disallowed the question, recognizing it was an attempt to elicit an inadmissible opinion from a witness. See Matthews, 296 S.C. at 393, 373 S.E.2d at 595.

PROPORTIONALITY REVIEW

As required, we conduct a proportionality review of Appellants death sentence. S.C.Code Ann. 16-3-25(C) (2003). The United States Constitution prohibits the imposition of the death penalty when it is either excessive or disproportionate in light of the crime and the defendant. State v. Copeland, 278 S.C. 572, 590, 300 S.E.2d 63, 74 (1982). In conducting a proportionality review, we search for similar cases in which the death sentence has been upheld. Id.; S.C.Code Ann. 16-3-25(E) (2003).

After reviewing the entire record, we conclude the death sentence was not the result of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor, and the jurys finding of statutory aggravating circumstances for each of the four murders is supported by the evidence. Furthermore, a review of prior cases shows the death sentence in this case is proportionate to that in similar cases and is neither excessive nor disproportionate to the crime. See State v. Shuler, 353 S.C. 176, 577 S.E.2d 438 (2003) (death penalty warranted for defendant convicted of murders of former live-in lover, lovers thirteen year-old daughter, and lovers mother; aggravating circumstances included two or more persons were murdered pursuant to one scheme or course of conduct, and murder was committed during commission of burglary); State v. Wilson, 306 S.C. 498, 413 S.E.2d 19 (1992) (death penalty warranted where defendant was convicted of two counts of murdering two schoolchildren, eight counts of assault and battery with intent to kill, one count of assault and battery of a high and aggravated nature, and one count of illegally carrying a firearm in shootings at an elementary school); State v. Hughey, 339 S.C. 439, 529 S.E.2d 721 (2000) (death penalty warranted where defendant shot and killed former girlfriend and another woman in a home); State v. Rosemond, 335 S.C. 593, 518 S.E.2d 588 (1999) (death penalty warranted where defendant shot and killed former girlfriend and her young daughter in their home); State v. Reed, 332 S.C. 35, 503 S.E.2d 747 (1998) (death penalty warranted where defendant shot and killed both parents of his former girlfriend).

AFFIRMED.