Executed November 18, 2011 9:15 p.m. by Lethal Injection in Idaho

43rd murderer executed in U.S. in 2011

1277th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Idaho in 2011

2nd murderer executed in Idaho since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

(43) |

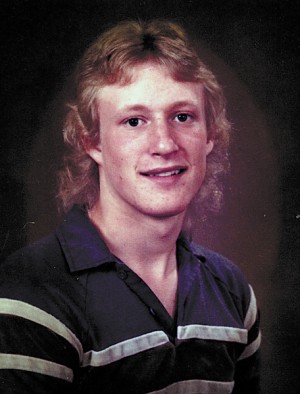

Paul Ezra Rhoades W / M / 30 - 54 |

Stacy Dawn Baldwin W / F / 21 Nolan Haddon W / M / 23 Susan Michelbacher W / F / 34 |

03-17-87 03-19-87 |

1988 05-24-88 |

Summary:

Rhoades was convicted in three separate kidnapping and murder cases. For the murders of Susan Michelbacher and Stacy Baldwin, Rhoades was sentenced to death, and for the murder of Nolan Haddon he received an indeterminate life sentence based on a guilty plea. On February 28, 1987, 21 year old Stacy Dawn Baldwin was abducted while working at the Red Mini Barn convenience store in Blackfoot. She was then taken to a secluded location and shot several times. She died approximately an hour and a half later. On March 17, 1987, Nolan Haddon, a 23 year old student, was shot five times while working at Buck's convenience store in Idaho Falls. His body body was found in the store's walk-in cooler. On March 19, 1987 - Susan Michelbacher, 34, a special education teacher, was abducted in a parking lot at 7 a.m., forced to withdraw money from her checking account, driven to a rural location, raped and shot nine times, resulting in her death.

Rhoades was a high school dropout who began drinking at the age of 10, suffered polio as a child, and developed a serious methamphetamine addiction as an adult.

Citations:

State v. Rhoades, 120 Idaho 795, 820 P.2d 665 (Idaho 1991). (Baldwin Direct Appeal)

State v. Rhoades, 121 Idaho 63, 822 P.2d 960 (Idaho 1991). (Michelbacher Direct Appeal)

State v. Rhoades, 135 Idaho 299, 17 P.3d 243 (Idaho 2000). (Baldwin PCR)

State v. Rhoades, 148 Idaho 247, 220 P.3d 1066 (Idaho 2009). (Haddon PCR)

Rhoades v. Henry, 638 F.3d 1027 (9th Cir. 2011). (Baldwin Habeas)

Rhoades v. Henry, 598 F.3d 511 (9th Cir. 2010). (Haddon Habeas)

Rhoades v. Henry, 611 F.3d 1133 (9th Cir. 2010). (Michelbacher Habeas)

Final/Special Meal:

Rhoades was offered hot dogs, sauerkraut, mustard, ketchup, onions, relish, baked beans, veggie sticks, ranch dressing, fruit with gelatin and strawberry ice cream cups — the same meal that was offered to all Idaho Maximum Security inmates.

Final Words:

"To Bert Michelbacher, I am sorry for the part I played in your wife's death. For Haddon and Baldwin, I can't help you. You still have to keep looking. I'm sorry for your family. I can't help you. I took part in the Michelbacher murder, I can't help you guys. I'm sorry." Rhodes then told his mom "goodbye." He then turned to the executioner or the warden and uttered, "I forgive you, I really do."

Internet Sources:

"Idaho executes inmate for 1987 slayings," by Rebecca Boone. (11/18/11)

BOISE, Idaho — Idaho prison officials executed Paul Ezra Rhoades on Friday for his role in the 1987 murders of two women, marking the state's first execution in 17 years.

Rhoades, 54, was declared dead at 9:15 a.m. at the Idaho Maximum Security Institution after being administered three separate drugs that make up the state's new lethal injection protocol. In his final words, Rhoades apologized for one of the murders, bid goodbye to his mother, and forgave state officials for the execution. "I forgive you. I really do," he said.

Rhoades was convicted in the kidnapping and murders of 34-year-old Susan Michelbacher and 21-year-old Stacy Dawn Baldwin. He was also sentenced to life in prison for the murder of 20-year-old Nolan Haddon.

The execution was witnessed by representatives of all three of the victims' families, Rhoades' mother, Pauline Rhoades, and four members of Idaho media. It appeared to go according to protocol, witnesses said. Rhoades delivered his final statement while lying on his back, strapped to a table. He seemed antsy, occasionally tapping his hand on the table. In a clear, loud voice, Rhoades apologized to Michelbacher's husband for her murder but did not take responsibility for the other two slayings. "To Bert Michelbacher, I'm sorry for the part I played in your wife's death," he said. Michelbacher did not attend the execution; but friends of the Michelbacher family were in attendance. "For Haddon and for Baldwin, you still have to keep looking. I can't help you," Rhoades said. "I'm sorry for your family. I can't help you."

After that statement, Baldwin's brother quietly said, "He lied the whole way through." Julie Haddon, Nolan Haddon's mother, commented, "What a coward." The time from initial injection to declaration of death was 22 minutes.

Brian Edgerton, a long-time family friend of the Michelbachers, told the AP after the execution that he felt a sense of relief, as well as continued grief over Susan Michelbacher's murder. He helped search for Michelbacher after she was reported missing, and said that everyone who knew her was devastated. "It's amazing how much is still there after all this time," Edgerton said. "A psychologist said there's always going to be a gnawing pain - it never completely heals. This helps a lot to move on and do the best we can to go forward." The other victims' family members seemed to feel the same way, he said. "I think that was felt by several of the families - a sense of peace and closure," Edgerton said.

Rhoades' attacks on Michelbacher, Baldwin and Haddon were brutal and his death was long overdue, Edgerton said, calling the execution "the appropriate, compelling and lawful consequence of these heinous crimes." The killings of Michelbacher, Baldwin and Haddon occurred during a three-week span in the winter of 1987. Prosecutors said Rhoades snatched Michelbacher, a special education teacher, into his van, raped her, shot her nine times and continued the sexual assault either as she lay dying or after she was already dead. Baldwin died in similar fashion. The newlywed and convenience store worker was abducted at gunpoint and taken to a remote area where prosecutor said he intended to sexually assault her. She fought back, and as she was scrambling away on all fours, he shot her twice and left her to die alone in the snow. Haddon also worked at a convenience store. He had long hair, and investigators speculated that Rhoades may have mistaken him for a young woman because of his blond locks. In any case, Rhoades robbed the convenience store, shooting Haddon five times and leaving him for dead in a walk-in cooler. Haddon died several hours later.

Rhoades, an Idaho Falls native, was the first Idaho inmate to be executed since 1994 and the only person to be involuntarily put to death in the state since 1957. The last inmate to be executed gave up all of his remaining appeals and asked the state to carry out his lethal injection.

The execution was the target of protests by capital punishment activists outside the prison south of Boise. Early Friday, about 50 people braved the cold and wind to protest at the prison's entrance. Some of them sat on the ground in silence, while others prayed collectively and waved signs with messages such as "What Would Jesus Do?" Across the street, about a half-dozen people gathered in a fenced-off area designated for supporters of the death penalty.

Rhoades admitted committing the murders, but he and his lawyers have vigorously appealed his case and Idaho's new execution protocols and procedures. On Thursday, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denied a request for a full judge's panel to review their appeal, and Rhoades' attorneys also filed a last-ditch appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. The high court cleared the way for the state to proceed.

A section of the state's protocol that barred media witnesses from viewing the first part of the execution was also subject to a separate challenge. Under the state's procedure, media witnesses were not allowed to see the execution team bring Rhoades into the chamber, secure him or insert the IVs. Media cited a 2002 California case in which the 9th U.S. Circuit Court ruled the public - through media representatives - had a First Amendment right to view an execution in its entirety. The Department of Correction rejected requests from various Idaho newspapers, The Associated Press and broadcast groups to change the policy in the days leading up to the execution.

Rhoades, who is a diabetic, was in fair health during his final days, though he was anxious about the coming execution, said Ray, the corrections spokesman. The department planned to cremate his body after the execution and give the remains to Rhoades' attorney, Oliver Loewy.

Rhoades was a high school dropout who began drinking at the about the age of 10, suffered polio as a child and developed a serious methamphetamine addiction as an adult.

"Rhoades defiant to the end; Paul Rhoades apologized for one murder but told the other two families, ‘I can’t help you.’ by Rebecca Roone. (ASSOCIATED PRESS 11/19/11)

Idaho prison officials executed Paul Ezra Rhoades on Friday for his role in the 1987 murders of two women, marking the state’s first execution in 17 years. Rhoades, 54, was declared dead at 9:15 a.m. at the Idaho Maximum Security Institution after being administered the three drugs that make up the state’s new lethal injection protocol. In his final words, Rhoades said he was sorry for one of the murders, bid goodbye to his mother and forgave state officials for the execution. “I forgive you. I really do,” he said.

Rhoades was convicted in the kidnapping and murders of 34-year-old Susan Michelbacher and 21-year-old Stacy Dawn Baldwin. He was also sentenced to life in prison for the murder of 20-year-old Nolan Haddon. The execution was witnessed by representatives of all three of the victims’ families; Rhoades’ mother, Pauline Rhoades; and four Idaho reporters. It appeared to go according to protocol, witnesses said.

A CLEAR VOICE

Rhoades delivered his final statement while lying on his back, strapped to a table. He seemed antsy, occasionally tapping his hand on the table. In a clear, loud voice, Rhoades apologized to Michelbacher’s husband for her murder but did not take responsibility for the other two slayings. “To Bert Michelbacher, I’m sorry for the part I played in your wife’s death,” he said. Michelbacher did not attend the execution, but friends of the Michelbacher family were in attendance. “For Haddon and for Baldwin, you still have to keep looking. I can’t help you,” Rhoades said. “I’m sorry for your family. I can’t help you.”

After that statement, Baldwin’s brother quietly said, “He lied the whole way through.” Julie Haddon, Nolan Haddon’s mother, commented, “What a coward.” The time from initial injection to declaration of death was 22 minutes.

Brian Edgerton, a long-time family friend of the Michelbachers’, told the AP after the execution that he felt a sense of relief, as well as continued grief over Susan Michelbacher’s murder. He helped search for Michelbacher after she was reported missing, and said that everyone who knew her was devastated. “It’s amazing how much is still there after all this time,” Edgerton said. “A psychologist said there’s always going to be a gnawing pain — it never completely heals. This helps a lot to move on and do the best we can to go forward.” The other victims’ family members seemed to feel the same way, he said. “I think that was felt by several of the families — a sense of peace and closure,” Edgerton said.

‘HEINOUS CRIMES’

Rhoades’ attacks on Michelbacher, Baldwin and Haddon were brutal, and his death was long overdue, Edgerton said, calling the execution “the appropriate, compelling and lawful consequence of these heinous crimes.” The killings of Michelbacher, Baldwin and Haddon occurred during a three-week span in the winter of 1987. Prosecutors said Rhoades snatched Michelbacher, a special education teacher, into his van, raped her, shot her nine times and continued the sexual assault either as she lay dying or after she was already dead. Baldwin died in similar fashion. The newlywed and convenience store worker was abducted at gunpoint and taken to a remote area where prosecutors said he intended to sexually assault her. She fought back, and as she was scrambling away on all fours, he shot her twice and left her to die alone in the snow. Haddon also worked at a convenience store. He had long hair, and investigators speculated that Rhoades may have mistaken him for a young woman because of his blond locks. In any case, Rhoades robbed the convenience store, shooting Haddon five times and leaving him for dead in a walk-in cooler. Haddon died several hours later.

VIGOROUS APPEALS

Rhoades, an Idaho Falls native, admitted committing the murders, but he and his lawyers vigorously appealed the case and Idaho’s new execution protocols and procedures. On Thursday, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denied a request for a full judge’s panel to review their appeal, and Rhoades’ attorneys also filed a last-ditch appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. The high court cleared the way for the state to proceed. The last inmate to be executed in Idaho, in 1994, gave up all of his remaining appeals and asked the state to carry out his lethal injection. A section of the state’s protocol that barred media witnesses from viewing the first part of the execution was also subject to a separate challenge. Under the state’s procedure, media witnesses were not allowed to see the execution team bring Rhoades into the chamber, secure him or insert the IVs.

FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHT TO VIEW DEATH

Media cited a 2002 California case in which the 9th U.S. Circuit Court ruled the public — through media representatives — had a First Amendment right to view an execution in its entirety. The Department of Correction rejected requests from the Statesman and other Idaho newspapers, The Associated Press and broadcast groups to change the policy in the days leading up to the execution. Rhoades, who was a diabetic, was in fair health during his final days, though he was anxious about the coming execution, said Correction Department spokesman Jeff Ray. The department planned to cremate his body after the execution and give the remains to Rhoades’ attorney, Oliver Loewy.

Rhoades was a high school dropout who began drinking at about the age of 10, suffered polio as a child and developed a serious methamphetamine addiction as an adult.

"Rhoades' last hours; Idaho's first execution in 17 years set for Friday." (11/18/11)

Twenty-four years after Idaho sentenced him to death, Paul Ezra Rhoades is slated to die today by lethal injection at 8:10 a.m. Here is what we know about his final days.

Lawyers for the Death Row inmate asked the U.S. Supreme Court Thursday to stop the execution. That request was denied. Rhoades will be the first person executed in Idaho since 1994 and the only one to be put to death against his will since 1957 — the year he was born.

The Department of Correction gave these details Thursday:

LAST MEAL: Rhoades was offered hot dogs, sauerkraut, mustard, ketchup, onions, relish, baked beans, veggie sticks, ranch dressing, fruit with gelatin and strawberry ice cream cups — the same meal that was offered to all Idaho Maximum Security inmates Thursday night.

VISITORS: He was able to have family members visit until 8:30 p.m. and make phone calls until 9 p.m. His attorney, Oliver Loewy, and his spiritual adviser may be with him until 6 a.m. The adviser asked IDOC not to identify him.

CARD: All but one of the other Death Row inmates signed a card for Rhoades.

CREMATION: Rhoades’ body will be cremated and his remains given to his attorney.

WITNESSES: Representatives from all three of the victims’ families will attend the execution. IDOC is not disclosing their identities.

FAMILY: Rhoades’ mother will attend the execution.

CONDITION: Rhoades’ health is fair, his demeanor anxious and lucid.

ACTIVITIES: Rhoades has been watching TV, reading and doing artwork. He has been talkative with his family, attorney, spiritual adviser and the correctional officers who are monitoring him.

Idaho Department of Correction

Rhoades' Death Warrant Carried Out

BOISE, November 18, 2011 – Director Brent Reinke made the following statement to the media following today’s execution procedures. “Today, the Idaho Department of Correction carried out the court-order death warrants issued against Paul Ezra Rhoades for the crimes of first-degree murder and first degree kidnapping in Bonneville and Bingham counties. Paul Ezra Rhoades was pronounced dead at 9:15 a.m.”

Biographical information

Sex: male

Height: 6’ 2”

Weight: 259 lbs

Eyes: hazel

Hair: brown

Ethnicity: white

Complexion: fair

Birth date: 01/18/1957

Birthplace: Idaho Falls, ID

Rhoades' Case Summary

On January 26, 1988, Paul Ezra Rhoades, IDOC #26864, was found guilty in the 7th Judicial District Court for Bonneville County of the crimes of first degree murder and first degree kidnapping.

On March 4, 1988, the 7th Judicial District Court for Bonneville County made and entered its findings of the Court in considering the death penalty, finding that Rhoades is guilty of murder in the first degree and kidnapping in the first degree and imposing the sentence of death.

On March 11, 1988, Rhoades was found guilty in the 7th Judicial District Court for Bingham County of the crimes of first degree murder and first degree kidnapping.

On May 13, 1988, the 7th Judicial District Court for Bingham County made and entered its findings of the Court in considering the death penalty, finding that Rhoades is guilty of murder in the first degree and kidnapping in the first degree and imposing the sentence of death.

On October 11, 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear Rhoades' case.

On October 19, 2011, the IDOC served Rhoades with a death warrant as ordered by Seventh District Judge Jon J. Shindurling. The warrant ordered that Rhoades be executed on November 18, 2011.

On November 4, 2011, the Idaho Commission of Pardons and Parole decide to deny the petition for a commutation hearing submitted on behalf of Rhoades.

On November 14, 2011, a U.S. Magistrate Judge denied a stay of execution.

On November 16, 2011, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals denied an emergency stay.

On November 18, 2011, Rhoades was executed by lethal injection.

Planned schedule for November 18, 2011

4:00 a.m. Media center opens to pre-approved news media personnel

5:45 a.m. Selection of news media witnesses

6:00 a.m. Short news media briefing by IDOC Director Brent Reinke

7:00 a.m. IDOC van available for transport to demonstration area

7:15 a.m. News media witnesses transported to Idaho Maximum Security Institution

7:20 a.m. Offender is moved from isolation cell to execution chamber

7:30 a.m. IDOC van returns from demonstration area

7:45 a.m. Witnesses are escorted into execution chamber

8:00 a.m. IMSI’s warden reads death warrant to offender and witnesses

8:03 a.m. Warden asks offender if he wishes to make a final statement

8:07 a.m. IDOC’s director re-confirms that no legal impediments exist

8:10 a.m. Administration of chemicals begins

8:30 a.m. Coroner enters chamber, examines the condemned and pronounces death

9:30 a.m. News media briefing by IDOC Director Brent Reinke and media witnesses

10:30 a.m. Demonstration area closes

1:00 p.m. Media center closes

Paul Ezra Rhoades: Timeline

February 28, 1987 - Stacy Baldwin, 21, was shot after being abducted while working at the Red Mini Barn convenience store in Blackfoot. She put up a fight as Rhoades tried to sexually assault her. He shot her in the back as she was running away.

March 17, 1987 - Nolan Haddon, 23, was shot while working at Buck's convenience store in Idaho Falls. He was a student at a technical-vocational school. Haddon's body was found in the store's walk-in cooler.

March 19, 1987 - Susan Michelbacher, 34, was abducted in grocery store parking lot at 7 a.m., raped and shot to death.

March 25, 1987 - Paul Ezra Rhoades crashed his mother's car near Wells, Nevada, and walked to a nearby casino. Inside his car, police found the weapon and the same bullets used in the three murders. Detectives located Rhoades, playing blackjack in a casino.

March 24, 1988 - Rhoades was sentenced to death for the murder of Susan Michelbacher by Seventh District Judge Larry M. Boyle.

May 13, 1988 - Rhoades was sentenced to death by Seventh District Judge James Herndon for the murder of Stacy Baldwin.

February 15, 1991 - The Idaho Supreme Court affirmed Rhoades' conviction and sentence in the Baldwin murder.

November 14, 1991 - The Idaho Supreme Court affirmed Rhoades' conviction and sentence.

May 24, 2007 - U.S. District Judge Edward Lodge denied Rhoades' petition for a writ of habeas corpus.

February 9, 2011 - The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals denied Rhoades' petition for rehearing in the Baldwin case.

October 11, 2011 - The United States Supreme Court denied Rhoades' petition for certiorari.

Nov. 15, 2011: Attorneys for Rhoades filed an emergency appeal to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, claiming that Idaho's new lethal injection protocol is likely to be botched, causing him to suffer excruciating pain in violation of the 8th Amendment.

Nov. 16, 2011: The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denies Rhoades' plea to stop the scheduled execution of Rhoades. His lawyer argued Idaho's new lethal injection policy is flawed and results in cruel and unusual punishment.

Kevin Richert: "Paul Ezra Rhoades’ last hurtful words," by Kevin Richert. (11/19/11)

In his last moments on the planet — 24 years removed from a three-week spree of unspeakable murderous violence — Paul Ezra Rhoades seized upon his one final chance to inflict harm upon his victims’ loved ones.

Rhoades accepted blame for his role in the killing of Susan Michelbacher, an Idaho Falls schoolteacher. His role, implying he did not act alone in her abduction, rape and shooting. He said the families of Stacy Dawn Baldwin and Nolan Haddon need to keep looking for a killer.

P>Rhoades managed to say he forgave the state workers who were about to inject him with a cocktail of lethal drugs. His mercy, still, never extended to the families of his victims. Even in his final, hurtful moments.

Final moments that are given added weight, and added public attention, when we as a society choose to carry out the death penalty.

Wherever you stand on the death penalty, it’s impossible not to feel first for those who knew and loved Rhoades’ victims. That, it seems, is simply a prerequisite to being a member of the human race.

I cannot begin to imagine what they have endured for 24 years, nor would I ever want to. It’s no one’s place to judge whether they are feeling, to use the overused phrase, a sense of closure. I only feel sorrow for them, especially in light of what they had to hear Friday morning.

AND MEANWHILE, ON THE MAINLAND ...

Before Idaho carried out its first execution in 17 years, Gov. Butch Otter had spent much of the week in Maui at a conference.

Bankrolled by the California Independent Voter Project, attendees at the Maui “Business and Leader Exchange” discussed presidential politics, reported Betsy Russell of the Spokane Spokesman-Review. The conference was held at the Fairmont Kea Lani Resort, she wrote, “a beachfront spread with three swimming pools, a 140-foot water slide and an array of luxury amenities.”

Back in Idaho, Otter released this statement Friday:

“My thoughts and prayers are with the victims, their loved ones, the mother of Paul Ezra Rhoades and everyone who has been impacted by these crimes. Mr. Rhoades took full and unfettered advantage of his right to due process of law for more than 20 years. That process has run its course and Mr. Rhoades has been held accountable for his actions. The state of Idaho has done its best to fulfill this most solemn responsibility with respect, professionalism and most of all dignity for everyone involved.”

Nice of Otter to check in.

This execution was the first to occur under the governor’s watch; an event of such magnitude should supercede a conference in Hawaii.

"Idaho inmate Paul Ezra Rhoades executed," by Jay Michaels. (Updated: Nov 19, 2011 at 12:48 AM MST)

BOISE, ID (KMVT) This morning the first person to be executed in Idaho in 17 years received a lethal injection and died at the State Penitentiary south of Boise. The inmate in question was charged with three Southeastern Idaho murders almost 25 years ago.

Paul Ezra Rhoades was sentenced to death for the 1987 kidnapping and murders of 34 year old Susan Michelbacher and 21 year old Stacy Dawn Baldwin. Following the 1987 murder of 20 year old Nolan Haddon, Rhoades was also sentenced to life in prison without parole.

At 9:15 a.m. this morning Rhoades, now 54 years old, was the first person executed in Idaho since 1994 and the only person to be involuntarily put to death in the state since 1957, the year he was born.

Local resident Dave Sylvester says, "I don't look at it as punishment. I just figure that person is so miserable, sitting there. I think that I would choose the death sentence, if it came down to it for myself."

Pastor Pedro Contreres says, "To me 20, 30, 50 years or maybe lifetime in prison, isn't that enough? The person can repent, and turn their life for the good one."

Local viewers also posted comments on KMVT's Facebook page, as well.

Jennifer says, "If it had been your mother, sister, wife, or girlfriend, you would want justice. Him in a prison cell with tv and free food is not justice."

Ivan says, "I don't want to keep paying for repeat offenders to get another chance to do the right thing. I've been through the system and I had help. The difference is I took the help I was given and made something of myself!"

And Sarah says, "Life is harder because life is something you have to deal with. ...Don't get me wrong, he got what he deserved, but he also got it easy."

"Rhoades addresses the victims' families, his mother, and executioners in final statement," by Kelsey Jacobson. (Saturday, Nov 19 at 8:53 AM)

BOISE -- Paul Ezra Rhoades was confirmed dead at 9:15 a.m. Friday.

Rhoades was killed by a lethal injection administered at 9:05 a.m.

The delay

The execution was scheduled to take place at 8 a.m. That was delayed after a motion was filed in court at 3 a.m. Friday. It took about a half hour for the motion to be reviewed. Shortly after that review, the Idaho Department of Corrections announced the execution would take place at 9:05 a.m., 55 minutes late.

"It was occasioned by a motion of stay that was filed at about 3 a.m. this morning," said Attorney General Lawrence Wasden following the time of death announcement. "At about 8 o'clock this morning, the state district court judge in Ada County issued a denial of that stay and the matter was able to proceed."

Rhoades was convicted of murder in 1987. He admitted to police he killed Susan Michelbacher, 34, and Nolan Haddon, 20.. He was also convicted in the murder of Stacy Baldwin, 21. He was sentenced in 1988.

Witness testimonials

The media representatives who witnessed the execution reported what they had seen in the execution chamber. Rebecca Boone is a reporter with the Associated Press. She described Rhoades' last words.

"Perhaps the most noteworthy thing was Mr. Rhoades' final statement. He apologized for the Michelbacher murder but did not take responsibility for the other two murders," said Boone. "He said, to Bert Michelbacher, 'I'm sorry for the part I played in your wife's death. For Haddon, you still have to keep looking. I can't help you, I'm sorry for your family. I can't help you, I took part in the Michelbacher death, I can't help you guys, sorry.'"

Boone continued to describe his final statement, "He continued, he faced the section that contained his representatives, and he said 'Mom, goodbye,' and then he turned and faced the warden Randy Blades and said, 'You guys, I forgive you, I really do.' And that was the end of his statement for the evening."

KIVI's Mac King also witnessed the execution. He said the entire thing was done very professionally, "The whole thing was incredibly sterile, with the exception of his statement. Everyone was very professional. Double and triple checking every step of the process and sterile is the best adjective or word I can put with the entire thing."

He also mentioned what the mood was like in the room when Rhoades made his statement and once the death was announced, "There were some tears on their part, they didn't really react when they did the statement but after he was pronounced dead there was definitely relief."

Nate Green with the Idaho Press Tribune was the third witness to address the media. He described what he thought was one of the most emotional parts of the execution.

"It was very quiet and somber, quiet throughout. Towards the end, one gentlemen, apparent friend of Michelbachers, said, 'The devil has gone home.' That was very emotional."

The process

Following witness testimonies, Ada County Coroner Erwin Sonnenberg talked about the process. He was present for Rhoades' execution Friday, as well as the 1994 execution of Eugene Wells.

"What I saw is what I would've expected," Sonnenberg described. "We're 27 years later, the first was done professional, as far as start to finish. Process was very much the same. What you expect to see different, is the changes in technology that have been implemented that were not available back then. It made it a lot better process because of technology, for my role in pronouncing the death, and seeing that everything went smoothly."

Sonnenberg continued describing the process, "We're monitoring the heart, you're seeing, as the different drugs are injected, you're seeing the heart respond accordingly to those drugs. Until you finally have the last drug administered, which would end up giving a flatline, and they run flatline for a few minutes to see if anything else was going on. Basically, we're just monitoring the heart, and how it's responding to the meds, and they responded just as we expected."

Finding closure

Following the execution, the mother of one of Rhoades' victims spoke with KTVB over the phone. Julie Haddon, mother of Nolan, said she feels relieved and is glad they are through having to hear about her son's murderer.

"The only thing that bothered me was when he couldn't help the Baldwill family because he didn't do it," said Haddon. "I was stunned. I don't know why, why would I expect anything better out of him."

Haddon also described what it was like being surrounded by the other victims' families.

"It was quite comforting in a way, they were all very nice people. We got to visit with and express our feelings together. It was good."

Tom Moss was the lead prosecutor in Bingham County at the time of the murders. He said he was not surprised with how the execution went and he does not have much reaction to what happened.

"I know what the evidence was, I feel very comfortable that he pleaded guilty to killing Nolan Haddon," said Moss. "There's no doubt in my mind that he killed Stacy Baldwin."

Moss was asked if he believes in the death sentence. He said the facts in a case determine whether a prosecutor seeks the death penalty, and in this case it was warranted, "Nothing brings total justice. It doesn't bring their loved ones back."

He added that he has tried other death penalty cases, but this is the first one to bring a certain amount of closure, "This case is closed."

"Mother of victim reacts to Rhoades' execution," by Justin Corr. (Friday, Nov 18 at 10:16 PM)

BOISE -- It's been 24 years since Julie Haddon received the news that her son was killed by Paul Ezra Rhoades. Friday, Rhoades was put to death and Haddon said justice was done.

Nolan Haddon died on March 17, 1987 when Paul Ezra Rhoades came into the convenience store Haddon was working at and shot the 20-year-old five times.

Friday, with Nolan on her mind, Julie Haddon saw her son's killer for the first time in more than two decades.

"Probably 22 or 23 years ago I saw him at a hearing in Idaho Falls," she said. "Been a long, long time."

But this time, Rhoades was strapped down on a table, about to be executed for his crimes. Watching with Julie was her husband, Junior, and other family members of Rhoades' victims.

"It was quite comforting, in a way," said Haddon. "They were all very nice people. We got to visit and express our feelings together. It was good."

Before the lethal injections were given, Rhoades said his final words.

"He said that he couldn't help the Haddons and the Baldwin family, because he didn't do it," said Haddon. "I was stunned, but I don't know why. Why would I expect anything better out of him?"

Then, it ended -- the execution, and the 24-year ordeal for Julie and other family members of Rhoades' victims.

"I actually feel good about it," said Haddon. "I didn't know how I was going to feel, but it isn't bothering me. I feel relieved. I'm glad it's over. I'm glad we're through having to hear about him. Justice has finally been served."

Julie and her husband went back to eastern Idaho on Friday. She said it will be nice to not have worry about Rhoades or his court proceedings ever again.

"Governor Otter releases statement on Rhoades' execution." (Posted on November 18, 2011 at 11:28 AM)

Governor C.L. "Butch" Otter released this statement today following the execution of Paul Ezra Rhoades:

"My thoughts and prayers are with the victims, their loved ones, the mother of Paul Ezra Rhoades and everyone who has been impacted by these crimes. Mr. Rhoades took full and unfettered advantage of his right to due process of law for more than twenty years. That process has run its course and Mr. Rhoades has been held accountable for his actions. The State of Idaho has done its best to fulfill this most solemn responsibility with respect, professionalism and most of all dignity for everyone involved."

Inmates Currently on Idaho's Death Row

Azad Abdullah Arrived: November 2004 Convicted of 1st degree murder for the arson death of his wife in Ada County.

David Card Arrived: September 1989 Shooting deaths of two people in Canyon County.

Thomas Creech Arrived: January 1983 Beating death of an inmate in Ada County

Timothy Dunlap Arrived: April 1992 Convicted of 1st degree murder for killing a woman during a bank robbery in Caribou County.

Zane Fields Arrived: August 1991 Convicted of 1st degree murder for a stabbing death in Ada County.

James Hairston Arrived: November 1996 Convicted of 1st degree murder for two shooting deaths in Bannock County

Erick Hall Arrived: October 2004 Convicted of two counts of 1st degree murder for raping and killing two women in Ada County in 2000 and 2003.

Michael Jauhola Arrived: May 2001 Convicted of 1st degree murder for the 2001 beating death of a fellow inmate.

Richard Leavitt Arrived: December 1985 Convicted of 1st degree murder for a mutilation and stabbing death in Bingham County.

Darrell Payne Arrived: May 2002 Convicted of 1st degree murder for the death of a woman in Ada County

Gerald Pizzuto Arrived: May 1986 Convicted of 1st degree murder for beating to death two people in Idaho County.

Paul Rhoades Arrived: March 1988 Convicted of 1st degree murder for kidnapping and raping two women in Bonneville County. Convicted of 1st degree murder and kidnapping in Bingham County.

Robin Row Arrived: December 1993 Convicted of 1st degree murder for the arson deaths of her husband, son and daughter in Ada County.

Lacey Sivak Arrived: December 1981 Convicted of 1st degree murder for killing gas station attendant during a robbery.

Gene Stuart Arrived: December 1982 Convicted of 1st degree murder for the beating death of a three-year-old boy in Clearwater County.

"Triple killer Rhoades executed in Idaho," by Betsy Z. Russell. (November 18, 2011)

BOISE - Triple murderer Paul Ezra Rhoades was executed this morning despite repeated last-minute appeals, in Idaho’s first execution since 1994 and only its second since 1957.

“The execution of Paul Ezra Rhoades has been carried out in the manner that was prescribed by law in the state of Idaho,” state Corrections Director Brent Reinke said. “Death of the prisoner was pronounced at 9:15 a.m.”

In his final words, Rhoades took responsibility for one of the murders, but not the other two. A friend of the family of one of the victims, who was in the chamber witnessing the execution, said, “The devil has gone home.”

Another family member commented, “What a coward.”

Unlike the last person executed in Idaho, double murderer Keith Eugene Wells, who dropped all appeals and asked to be put to death, Rhoades pursued every appeal possible, including a last-ditch appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court the night before his execution. None worked.

Rhoades earlier admitted his crimes, which terrorized an eastern Idaho community for three weeks in 1987. His appeals have focused mostly on technicalities and on his abusive childhood and drug addiction. He said he had changed in his quarter-century in prison. He also challenged Idaho’s lethal-injection execution method as cruel.

Rhoades received the death sentence for the kidnappings and murders of 34-year-old Susan Michelbacher and 21-year-old Stacy Dawn Baldwin in 1987. He also was sentenced to life in prison without parole for the 1987 murder of 20-year-old Nolan Haddon, to which he pleaded guilty.

Associated Press reporter Rebecca Boone, who witnessed the execution, said Rhoades, after apologizing for the Michelbacher murder, said to the families of his other two victims, “I can’t help you guys, sorry.”

She said a family member of one of the victims said, “He’s been lying the whole way through.”

Rhoades, lying on his back strapped to a gurney with IVs running to deliver the drugs that would kill him, said, “‘Mom, goodbye,’ then he turned and faced the warden, Randy Blades, and said, ‘You guys, I forgive you, I really do,’” Boone reported.

ABC Channel 6 reporter Mac King said, “The whole thing was incredibly sterile, with the exception of his statement. Everyone was really professional.” King said there were “some tears” from the victims’ families. King was among four reporters who witnessed the execution on behalf of the public.

About 45 people gathered in a circle in the freezing darkness outside Idaho’s state prison complex early in the morning to protest capital punishment, as the clock ticked toward the time for Rhoades to die by lethal injection.

“This is a heartbreaking morning,” said Mia Crosthwaite of Idahoans Against the Death Penalty.

Reinke, asked about Rhoades’ demeanor prior to the execution proceedings, said, “He’s very serious. He understands what is about to happen. His spiritual adviser and his attorney have been with him throughout the night.”

Addressing the media in the chill of the early morning, Reinke said, “The law requires and justice demands that Mr. Rhoades be held accountable. … Today we carry out the execution order.”

All Idaho state prisons, statewide, were on lockdown and high alert during the execution proceedings, Reinke said.

Tom Moss, who prosecuted Rhoades in 1987 and later served as U.S. attorney for Idaho, said after the execution, “Nothing brings total justice. They don’t get their loved ones back. But it brings some satisfaction to them.”

He said, “I’ve often said I don’t think I will live to see anybody executed. So there’s a certain amount of closure to see one of ‘em get executed. … There is satisfaction to see finally the law comes to its conclusion, it’s done. These families don’t have to read any more in the paper about there’s something going on with Paul Rhoades. … This case is closed.”

Paul Ezra Rhoades had been loitering around convenience stores in the Blackfoot and Idaho Falls area, including the Red Mini Barn in Blackfoot. Stacy Baldwin worked at the Red Mini Barn and began her night shift around 9:45 p.m. on February 27, 1987. Some time before 11:00 p.m., Carrie Baier and two other girls rented videos at the Mini Barn from Stephanie Cooper, Baldwin’s co-worker. Cooper’s shift ended at 11:00 p.m, which left Baldwin alone.

When Baier returned around midnight, she noticed a man leave the store, get into a pickup truck (it turned out to be one used by the Rhoades family), and drive recklessly toward her. Baier saw a passenger next to the driver, but neither she nor her friends could identify the driver or the passenger. Baier went into the Mini Barn but could not find Baldwin, though Baldwin’s coat was still there and her car was outside. The last recorded transaction at the store was at 12:15 a.m. $249 was missing from the cash register. Rhoades and another male had coffee at Stan’s Bar and Restaurant, near the Mini Barn, sometime between 1:30 a.m. and 2:00 a.m. on February 28. Baldwin’s body was found later that morning near some garbage dumpsters on an isolated road leading to an archery range. She had been shot three times.

According to a pathologist, Baldwin died from a gunshot wound to the back and chest, but may have lived for an hour or so after the fatal shot was fired. On March 22 or 23, Rhoades’s mother reported her green Ford LTD had been stolen. Rhoades was seen driving a similar looking LTD on March 22, and on March 24, truckers saw the LTD parked on a highway median in Northern Nevada. They also saw a person matching Rhoades’s description lean out of the car, fumble with a dark brown item, and run off into the sagebrush. A Nevada trooper responding to the scene found a .38 caliber gun on the ground near the open door of the car, and a holster about forty-five feet away. Ballistics testing would show that this weapon had fired the bullets that killed Baldwin.

Rhoades turned up about 11:00 in the morning of March 25 at a ranch a mile and a half from where the LTD was found. Later that day, he got a ride from the ranch to Wells, Nevada, where he was dropped off at the 4 Way Casino around 9:00 p.m. Nevada law enforcement officers arrested Rhoades while he was playing blackjack. They handcuffed him, set him over the trunk of the police car, and read him his Miranda rights. Meanwhile, Idaho authorities were alerted to a Rhoades connection when the LTD was discovered. They had previously obtained a warrant for Rhoades’s arrest for burglary of Lavaunda’s Lingerie, and arrived at the 4 Way Casino shortly after Rhoades was arrested. As the Idaho officers — one of whom Rhoades knew from home — approached, Rhoades said: “I did it.”

Rhoades was advised of his Miranda rights by an officer from Idaho, Victor Rodriguez, and searched by another Idaho officer, Dennis Shaw. Rhoades had a digital wrist watch in his pocket, which he claimed to have found in a “barrow pit.” It was just like the one Baldwin was wearing the night she was killed. During the booking process at the Wells Highway Patrol Station, Shaw remarked something to the effect: “If I had arrested you earlier, Stacy Baldwin may be alive today.” Rhoades replied: “I did it.” Shaw then said, “The girl in Blackfoot,” and Rhoades again replied, “I did it.”

Forensic analysis would show that footprints found in the snow near Baldwin’s body were consistent with the size and pattern of Rhoades’s boots, and that Rhoades’s hair was consistent with a hair on Baldwin’s blouse. Rhoades also admitted to a cellmate that he kidnapped Baldwin, took her to an archery range intending to rape her but was unable to do so because she was hysterical, and shot her twice in the back. Based on this evidence, the jury found Rhoades guilty of murder in the first degree, kidnapping in the first degree, and robbery. The state court held an aggravation and mitigation hearing, after which it sentenced Rhoades to death on the conviction for first degree murder and the conviction for first degree kidnapping.

In 1987, Paul Ezra Rhoades was charged with the rape and murder of Susan Michelbacher as well as the murder and robbery of Nolan Haddon. Rhoades pleaded not guilty to all charges and filed a motion to sever the charges, which was subsequently granted. Rhoades was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death on the charges relating to the Michelbacher rape and murder. The parties subsequently entered into a plea agreement relating to the Haddon murder/robbery wherein Rhoades entered an “Alford” plea, maintaining his innocence in the case but conceding that “a conviction may be had on the charges as presently filed.” Rhoades was sentenced to serve concurrent indeterminate life sentences for the Haddon murder and robbery.

The evidence that would have been introduced at a trial for the Haddon murder included the gun used to kill Haddon found in the vicinity of a green car abandoned by Rhoades, statements made by Rhoades at the time of his arrest, and statements allegedly made to a jailhouse informer. Further evidence would have included witness testimony placing a car matching the description of the car in which Rhoades was found at the scene of the Haddon murder, law enforcement officers' testimony that items found in Rhoades' possession were similar to the items taken at the time of the Haddon robbery, and testimony regarding Rhoades' purchase of bullets matching the caliber of those used in Haddon?s murder. The gun is notable in the present case as the same gun was presented as the murder weapon in the case relating to the rape and murder of Susan Michelbacher.

Nolan Haddon worked the night shift at Buck’s convenience store in Idaho Falls, Idaho on March 16, 1987. The next morning, Buck’s owner found Haddon lying on the floor in a pool of blood. He had been shot five times. He was still alive at the time, but unconscious. He died at the hospital. An inventory of the store showed that some BIC lighters, Marlboro cigarettes, and $116 in cash were missing. The police suspected Rhoades of a string of burglaries, including one at Lavaunda’s Lingerie, and obtained a warrant to arrest Rhoades for that burglary on March 23, 1987. They learned that he was in Nevada when, on March 24, a Nevada state trooper responded to an accident involving a green Ford that was reported stolen by Rhoades’s mother, Pauline Rhoades. The next evening, two Nevada law enforcement officers arrested Rhoades inside a Wells Casino. They handcuffed him, placed him across the trunk of the police car, and advised him of his Miranda rights. Idaho officials were contacted and went to the Casino. As the Idaho team approached, Rhoades stated “I did it” without being questioned by anyone. Officer Victor Rodriguez, from Idaho, again advised Rhoades of his Miranda rights. Rhoades was asked if he understood those rights, and said something to the effect of “I do, yes.”

Detective Dennis Shaw, also from Idaho, searched Rhoades, and found two packages of Marlboro cigarettes and five BIC lighters similar to those taken from the store. Shaw also found a ten dollar bill, a one dollar bill, and a one-hundred dollar bill. He told Rhoades he had found three dollars, to which Rhoades responded: “It better be $111.” Rhoades was then taken to the Wells Highway Patrol substation for booking. At the station, Shaw remarked that he wished he had arrested Rhoades on an earlier occasion, and that he would probably have saved the last victim’s life. Rhoades raised his head and said, “I did it.”

RHOADES Paul Ezra

An Idaho native, born in 1957, Rhoades boasted a record of small-time arrests dating from age 21. In May 1978, he was charged with refusal to disperse, and grand theft charges were filed against him six months later, the latter count dismissed prior to trial. A new charge of refusal to disperse was lodged in March 1982, and June of that year saw him booked for petty theft. Rhoades was arrested for driving without a license in June 1985 and again in March 1986, but more serious charges of burglary were dismissed in January 1986. So far, he had been lucky, but police were only chipping at the apex of a lethal iceberg. If the authorities are right in their suspicions, Rhoades began his hunt for human prey in the adjoining state of Utah, gunning down 16-year-old Christine Gallegos, in Salt Lake City, during May 1985. Eleven months later, 20-year-old Carla Maxwell was shot to death in the robbery of a Layton, Utah, convenience store. Lisa Strong, age 25, was the third Utah victim, blasted on a Salt Lake City street in May 1986.

On February 27, 1987, Stacy Baldwin, 21, was kidnapped from her job at a convenience store in Blackfoot, Idaho, shot dead and dumped outside the city limits. Officers saw no connection four days later, when a 19-year-old college co-ed was abducted, robbed, and raped in Rexburg, but the links would show, in time. On March 16, 20-year-old Nolan Haddon was fatally wounded in the robbery of an Idaho Falls convenience store. Three days later, Susan Michelbacher, a 34-year-old schoolteacher, vanished en route to her classes in Idaho Falls. She was discovered, shot to death outside of town, March 21. Paul Rhoades, meanwhile, had fled the city in his mother's car, the vehicle reported to police as stolen. He was picked up in Elko, Nevada, on March 25, after a traffic accident led to identification of the missing car. Ballistics tests matched a confiscated revolver to the three deaths in Idaho, and warrants were issued charging Rhoades with murder, kidnapping, robbery, rape, and "an infamous crime against nature." The courts ruled out an insanity plea in November 1987, and Rhoades was held over for trial on the outstanding charges.

State v. Rhoades, 119 Idaho 594, 809 P.2d 455 (Idaho 1991). (Haddon Direct Appeal)

Defendant entered conditional guilty plea to second-degree murder and robbery and was sentenced to indeterminate life sentences by the District Court, Seventh Judicial District, Bonneville County, Larry M. Boyle, J., and subsequently appealed issues reserved in plea agreement. The Supreme Court, McDevitt, J., held that: (1) justiciable issue did not exist with respect to whether abolition of insanity defense deprived defendant of due process rights; (2) prosecution was not required to prove reliability of inculpatory statements by any higher standard than beyond reasonable doubt in capital case; (3) defendant's negative shake of head after being read Miranda warnings was not assertion of his right to remain silent justifying suppression of inculpatory statements subsequently made; (4) testimony of jailhouse informants as to defendant's purported confession to murder was not more prejudicial than probative; and (5) judge was not required to disqualify himself because he had sentenced defendant to death in earlier murder trial. Affirmed. Bakes, C.J., concurred specially with regard to Parts I and III of opinion with note. Johnson, J., concurred in result and concurred specially with Parts I, II and V of opinion with note.

McDEVITT, Justice.

This case arises from the murder of Nolan Haddon, a convenience store clerk, during the course of a robbery. Paul Ezra Rhoades was charged with that murder, and after pretrial proceedings he entered a conditional guilty plea to second degree murder and robbery. The trial court accepted the plea agreement and sentenced Rhoades to an indeterminate life sentence for murder in the second degree, and an indeterminate life sentence for robbery.

By the terms of the plea agreement, Rhoades reserved for appeal the issues discussed below, except that the issue of prosecutorial misconduct in withholding exculpatory evidence from the defense was not listed as an issue preserved for appeal by the plea agreement.

* * *

Prior to facing charges for the murder of Nolan Haddon, Rhoades was tried and convicted for the murder of Susan Michelbacher by a jury, and sentenced to death by the same judge who presided over the Haddon case. In deciding that the death penalty was appropriate for the Michelbacher homicide, the trial judge made detailed findings of fact, as required by statute. Those findings, weighing the aggravating and mitigating factors of the crime and Rhoades's character, concluded that, “[t]he murder and accompanying acts are those of someone morally vacant and totally devoid of conscience,” and that the circumstances of the crime were “extremely wicked and vile, shockingly evil, and designed to inflict a high degree of physical and mental pain with utter indifference to and with the apparent enjoyment of the suffering....” The judge also found that Rhoades has a propensity to commit murder and constitutes a continuing threat to society.

Rhoades moved to disqualify the trial judge from the Haddon case, arguing that after having reached such extreme and negative conclusions concerning the defendant, the trial judge could not possibly remain neutral during a second trial of the same person for a different crime.

A majority of the Court sitting on this case is of the opinion that this issue, as framed by the appellant, is not necessary to decide as the defendant was not sentenced to death in this case, or for the reason that the trial judge is able to carry out the duties of sentencing and still afford a defendant a fair trial in a subsequent proceeding.

SCHROEDER and REINHARDT, JJ., Pro Tem., concur. BAKES, C.J., concurs in result. JOHNSON, J., specially concurring.

* * *

Rhoades entered a conditional guilty plea to the murder of Nolan Haddon pursuant to Idaho Criminal Rule 11. That rule provides that if the appeal of issues raised in the conditional plea is successful, the defendant shall be entitled to withdraw the guilty plea and stand trial.

Our analysis has established no issue that constitutes reversible error thus permitting withdrawal of the plea entered by this appellant.

BAKES, Chief Justice, concurring specially:

With regard to Parts I and III, I agree with the Court that there was no evidence to raise a justiciable issue as to the constitutionality of the repeal of the insanity defense. However, if there had been, I agree with Justice Johnson that that issue is now foreclosed by virtue of our decision in State v. Searcy, 118 Idaho 632, 798 P.2d 914 (1990).

JOHNSON, Justice, concurring, concurring in the result and concurring specially:

I concur in the Court's opinion, except parts I–II (PRETRIAL RULING ON AVAILABILITY OF INSANITY DEFENSE) and part V (DISQUALIFICATION OF TRIAL JUDGE FOR PREJUDICE).

I concur in the result of parts I–II. In my view, there was a justiciable issue as to the constitutionality of the repeal of the insanity defense. However, this Court ruled in State v. Searcy, 118 Idaho 632, 798 P.2d 914 (1990) that the repeal of the insanity defense was not in violation of either the United States Constitution or the Constitution of the State of Idaho. Since no rehearing was requested in Searcy, a remittitur has issued, and the Court's opinion has become final. Although I dissented from this ruling of the Court in Searcy, I now accept that Searcy should be honored under the rule of stare decisis.

I concur specially in part V. In my view since the district judge who was the subject of the motion to disqualify did not sentence Rhoades to death in this case, I do not believe we should address the issue raised concerning his disqualification.

State v. Rhoades, 121 Idaho 63, 822 P.2d 960 (Idaho 1991). (Michelbacher Direct Appeal)

Defendant was convicted of capital murder and sentenced to death following jury trial by the Seventh Judicial District Court, Bonneville County, Larry M. Boyle, J. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, McDevitt, J., held that: (1) no judiciable controversy existed regarding constitutionality of statutory repeal of insanity defense; (2) prosecutor's reference to defendant's failure to testify was harmless error; (3) statute which required prompt postconviction proceedings did not violate defendant's procedural due process rights; (4) defendant's statements were admissible; (5) prosecutor's failure to produce two police reports did not affect outcome of trial; (6) jury instructions adequately informed jury of applicable laws; (7) setting deadline for production of defense expert report was not abuse of discretion; (8) erroneous admission of victim impact statements was harmless; (9) trial court properly considered alternatives to death penalty; (10) weapons enhancements were properly charged as separate counts; and (11) reasonable doubt jury instruction did not misstate to applicable law. Affirmed. Johnson, J., concurred specially, dissented, and filed opinion. Bistline, J., concurs in the result.

McDEVITT, Justice.

This case arises from the murder of Susan Michelbacher. Paul Ezra Rhoades has been convicted in three separate murder cases. For the murders of Susan Michelbacher and Stacy Baldwin, Rhoades was sentenced to death; for the murder of Nolan Haddon he received an indeterminate life sentence based on a conditional plea.

The issues presented in this appeal are:

I. Whether the legislative abolition of the defense of mental condition in criminal cases violates the Idaho or United States Constitutions.

II. Whether the trial court's failure to make a pretrial ruling on the constitutionality of the statutory abolition of the insanity defense was in error.

III. Whether comments made by the prosecuting attorney to the jury during closing argument violated the appellant's right to be free from compelled self-incrimination.

IV. Whether the trial court's limitation on juror inquiry into the effects of the prosecutor's comments constituted harmless error.

V. Whether accelerated post conviction procedures in capital cases are unconstitutional.

VI. Whether inculpatory statements made by Rhoades to the police should have been suppressed.

VII. Whether the prosecution's failure to turn over exculpatory evidence constituted reversible error.

VIII. Whether the jury instructions were proper.

IX. Whether the court erred in compelling a defense expert to prepare a written report or submit to an interview by the prosecutor before testifying.

X. Whether the court erroneously considered a victim impact statement.

XI. Whether the death penalty was properly imposed.

XII. Whether the jury was properly selected.

XIII. Whether the trial court's approval of the method of charging weapon enhancements was erroneous under statutory and case law.

I.–II. LEGISLATIVE ABOLITION OF THE INSANITY DEFENSE AND PRETRIAL RULING ON AVAILABILITY OF INSANITY DEFENSE

In 1982 the Idaho Legislature abolished the insanity defense in criminal cases by repealing I.C. § 18–209 and enacting I.C. § 18–207(a), which provides that “[m]ental condition shall not be a defense to any charge of criminal conduct.”

In this case, prior to trial, defense counsel filed a “Request for Declaration that the Enactment of § 18–207, I.C., the Repeal of §§ 18–208, 18–209, I.C. and the Repeal of Rule 12(g), I.C.R. are Unconstitutional.” It was urged that the abolition of the defense deprives criminal defendants of due process rights under the state and federal constitutions. The state filed a motion to quash this request, because, “an insanity defense has not been raised by the defendant and until such time as that issue is raised in good faith by the defendant such a request is an academic exercise as there is no issue in controversy.”

Both parties extensively briefed and argued the issue of justiciability; that is, whether there was any factual showing on the record that would grant the court the authority to render a ruling in the nature of a declaratory judgment on the issue. Rhoades had been examined by a psychiatrist pursuant to defense counsel's request. However, the defense did not introduce evidence indicating the psychiatrist's conclusions as to whether there was any basis on which to raise the issue of mental defect.

The defense contended that no showing was required under the unique circumstances of a capital case. The defense asserted that the court did have jurisdiction to render a declaratory judgment, in that the nature of a declaratory judgment is to clarify legal uncertainty, and having no legal definition of insanity made it impossible for a psychiatrist to render an opinion on whether Rhoades was legally insane.

The defense further argued that even if some showing was required, the prosecution and the court had waived the necessity of presenting preliminary evidence on Rhoades's mental condition when a defense request for psychiatric assistance at state expense was granted without the preliminary showing required by statute. The defense argues that this constituted a waiver of any showing that might be required in the later request for a ruling on the existence of the insanity defense.

Finally, the defense urged that there was a sufficient factual showing on the record to bring Rhoades's sanity into issue. Noting that where the insanity defense is permitted it may be established by lay testimony, the defense cited the preliminary hearing testimony of one of the arresting officers to the effect that on the night Rhoades was arrested he was unstable and incoherent.

The trial court held a hearing on the defense request for a “declaration,” which consisted of the court inquiring of defense counsel if he was asserting the defense of insanity, if he had an offer of proof that the sanity of the defendant was in question, or an opinion from the psychiatrist that examined the defendant. Defense counsel replied to each inquiry that he could offer no proof until he had a legal standard by which to define insanity.

THE COURT: Do you have an insanity defense that you are raising, or is this an academic exercise we're going through? ... If you have a defense, and you have an expert who is going to testify that this is an issue in this case, then I want to know that.

ATTORNEY: Your Honor, I'm sure the Court is thinking of Ake v. Oklahoma where the U.S. Supreme Court spoke on an indigent's right to have a psychiatrist appointed at public expense. The problem we have here, Your Honor, is there's little authority out of the Supreme Court in this area, that's one of the few cases that come even close to our situation.

THE COURT: My question is, though, do you have, after having Mr. Rhoades examined by a psychiatrist of your choosing, an opinion that the insanity issue is present in this case?

ATTORNEY: Your honor, may I have just a minute, I want to address the precise question the Court is posing to me. In light of Ake, we've been afforded the psychiatrist, ... and if you read the Ake decision, the Court explicitly states that the purpose of providing that psychiatrist at an early point is to allow the defense an opportunity to determine whether a defense is viable ... my point here today ... is that the psychiatrist does me no good unless we know what the law and legal standard is.

THE COURT: You're evading my question. My question, and I want an answer to it, is direct, do you have an opinion from your expert that the sanity of this defendant is in question?

ATTORNEY: Your Honor, I have no opinions from my expert at this time for the simple reason it was to be my next point, that until we know what the legal standard is for a possible sanity defense, defense of mental conditions excluding responsibility of the law, until we know what that is....

THE COURT: I'm going to go back, the question I'm concerned with is whether or not your expert who examined Mr. Rhoades months ago has rendered an opinion at any time indicating that there is a viable issue as to sanity or the ability of this man to understand what he did and to formulate an intent? I need an answer to that question, and we've danced around it, but we haven't had that directly presented to the Court. Has your expert given you any type of an opinion as to the mental condition of this defendant?

ATTORNEY: Your Honor, again I'm not sure I understand the question....

The trial court issued a Memorandum Decision refusing to rule on defendant's motion to find I.C. § 18–207 unconstitutional, finding that in the absence of expert testimony or evidence, there was no legitimate issue before the court. Defendant moved to appeal this decision, and another hearing was held. Again, the court asked defense counsel for an offer of proof, and again, none was given.

THE COURT: Let me ask you again as I did in August, do you have,—do you represent to this Court that you have expert testimony available to establish the viability of insanity defense in this case?

ATTORNEY: Well, I'll answer it the way I answered it. First of all, I don't know whether I do or not because a psychiatrist, forensic psychiatrist without a legal standard defining what insanity is could not possibly give me an opinion. That's where that sits.

Defendant's motion to appeal was denied.

We perceive the difficulty of the defense in obtaining an expert opinion on such a complex issue without the guiding framework of a legal standard. We also recognize that a psychiatric opinion on the mental condition of a defendant in a criminal case is forged by a long process of interaction between the expert and the defense, and that the result of that process will not generally be available during the pretrial stage of a criminal case.

However, the trial court did not require that the defense present an expert opinion as to the ultimate issue of Rhoades's sanity. The court requested any expression of opinion by the expert as to whether insanity might be an issue in the case, or an assertion by counsel that he was raising the defense of insanity. The court did not require polished testimony concerning exact mental processes or precise cognitive abilities of the defendant. It would have sufficed for the expert to provide a summary affidavit stating that in his opinion, there was a viable issue of insanity involved in the case. Alternatively, the expert might have submitted an affidavit to the effect that it would be impossible for him to render an opinion without a guiding legal standard. Yet another option might be to offer an opinion based on the definition of insanity that Idaho had in place prior to the legislative repeal of the defense, restricting the affidavit to an in camera review in order to protect the defense from the consequences of prematurely offering an opinion from an improperly prepared defense expert.

The trial court found that the record did not create a justiciable controversy to support a ruling on the issue of the repeal of the insanity defense. We agree.

The authority to render a declaratory judgment is bestowed by statute. The Declaratory Judgment Act, contained in Idaho Code Title 10, chapter 12, confers jurisdiction upon the courts with the option to “declare rights, status, and other legal relations, whether or not further relief is or could be claimed.” I.C. § 10–1201. An important limitation upon this jurisdiction is that, “a declaratory judgment can only be rendered in a case where an actual or justiciable controversy exists.” Harris v. Cassia County, 106 Idaho 513, 516, 681 P.2d 988, 991 (1984). This concept precludes courts from deciding cases which are purely hypothetical or advisory in nature.

Declaratory judgments by their very nature ride a fine line between purely hypothetical or academic questions and actually justiciable cases. Many courts have noted that the test of justiciability is not susceptible of any mechanistic formulation, but must be grappled with according to the specific facts of each case. Id.; 22 Am.Jur.2d Declaratory Judgments § 33, at 697. This Court, in Harris, adopted the following language from the United States Supreme Court's definition of justiciability as a guiding standard in the context of declaratory judgment actions:

[A] controversy in this sense must be one that is appropriate for judicial determination. A justiciable controversy is thus distinguished from a difference or dispute of a hypothetical or abstract character; from one that is academic or moot. The controversy must be definite and concrete, touching the legal relations of parties having adverse legal interests. It must be a real and substantial controversy admitting of specific relief through a decree of a conclusive character, as distinguished from an opinion advising what the law would be upon a hypothetical state of facts. Where there is such a concrete case admitting of an immediate and definitive determination of the legal rights of the parties in an adversary proceeding upon the facts alleged, the judicial function may be appropriately exercised although the adjudication of the rights of the litigants may not require the award of process or the payment of damages.

Aetna Life Ins. Co. v. Haworth, 300 U.S. 227, 241–42, 57 S.Ct. 461, 464, 81 L.Ed. 617 (1937) (citations omitted).

The same principle as pronounced by this Court provides:

The Declaratory Judgment Act ... contemplates some specific adversary question or contention based on an existing state of facts, out of which the alleged “rights, status and other legal relations” arise, upon which the court may predicate a judgment “either affirmative or negative in form and effect.”

* * * * * *

The questioned “right” or status” may invoke either remedial or preventative relief; it may relate to a right that has either been breached or is only yet in dispute or a status undisturbed but threatened or endangered; but in either or any event, it must involve actual and existing facts.

State v. State Board of Education, 56 Idaho 210, 217, 52 P.2d 141, 144 (1935).

In the present case, there are no actual and existing facts on the record. The record before the trial court, and before this Court, contains nothing more than the statement of counsel that he desired to inquire into the viability of the defense, and that although Rhoades had been examined by a psychiatrist, no opinion in any form as to Rhoades's mental state could be forthcoming unless the court provided an operative legal definition of insanity. As to the impossibility of offering an opinion without a legal standard to work with, the court had only the unsubstantiated statement of counsel to rely upon, there being no evidence from the expert. This unsworn statement does not provide a factual showing sufficient to create a justiciable issue before the court.

The testimony of Officer Rodriguez concerning Rhoades's manner on the night of his arrest likewise does not suffice to create a justiciable controversy on the issue of insanity. The officer stated during the preliminary hearing that on the night of the arrest:

Paul Rhoades was either acting as if he was high on some kind of narcotic, or he was high on some kind of narcotics.... [H]e really didn't have much stability ... he had to be helped to walk. He swayed back and forth when he sat down, almost in a drunken stupor. Didn't say too much, and when he did, he mumbled, as if, I would take it, he was not in control of his senses, ...

Other testimony confirms Officer Rodriguez's impressions of Rhoades's conduct on the night of the arrest, but there is no evidence in the record as to abnormal conduct at any other time. This testimony establishes that Rhoades was having physical difficulty on the night of his arrest, which was assumed by the officers to be the result of drugs or intoxication. The trial court appropriately concluded that such evidence alone does not rise to the level of a showing of the mental condition of the defendant.

The defense argues that any showing that might be required was waived by the prosecution at the time of the hearing on the defense request for appointment of a psychiatric expert at state expense. The United States Supreme Court, in Ake v. Oklahoma, 470 U.S. 68, 105 S.Ct. 1087, 84 L.Ed.2d 53 (1985), held that the defendant is constitutionally entitled to psychiatric assistance at state expense once a preliminary showing has been made that the mental condition of the defendant is likely to be an issue in the case. At the hearing, the prosecution represented that it had no objection to the appointment of a psychiatric expert, and further stated that:

From the state's point of view from what we understand the evidence to be we would understand why they seek these two particular appointments, so we would urge the Court to go ahead and adopt that without requiring any further showing.

Defense counsel urges that this statement by the prosecution, and the court's acquiescence in the motion for a court appointed expert without requiring any preliminary showing on the defendant's mental condition, amounts to a waiver of the required showing on the issue. We disagree.

Justiciability is a question of the jurisdiction of the court over the matter at issue. Baird v. State, 574 P.2d 713, 716 (Utah 1978); Mountain West Farm Bureau Mut. Ins. v. Hallmark Ins., 561 P.2d 706 (Wyo.1977). It is axiomatic that a lack of jurisdiction may not be cured by means of stipulation or waiver by the parties. Bowlden v. Bowlden, 118 Idaho 84, 794 P.2d 1140 (1990); White v. Marty, 97 Idaho 85, 540 P.2d 270 (1975), overruled on other grounds (1985). Therefore, this defense argument must be rejected.

We uphold the trial court's determination that the record does not create a justiciable controversy to support a ruling on the issue of the repeal of the insanity defense. Having done so, we do not reach the constitutional issue regarding the legislative repeal of the insanity defense.

III.–IV. COMMENT BY THE PROSECUTOR AND LIMITATION ON JUROR INQUIRY

In closing argument the prosecuting attorney made the following statements:

PROSECUTING ATTORNEY: When I get paid, when you get paid is that how you describe it that you came into some money? That's the phrase you use when you inherit some money or come into some other windfall. In today's world when money changes hands legitimately there's generally a document that documents that transaction. A receipt, a check, a passbook saving's account that indicates the transfer of those funds. What did we hear from the defendant yesterday?

DEFENSE ATTORNEY: Excuse me, Your Honor—

PROSECUTING ATTORNEY: I'm sorry—

DEFENSE ATTORNEY: I'm going to object.

PROSECUTING ATTORNEY: I'm sorry, what did we hear from the defense counsel in the case-in-chief yesterday?

Defense counsel suggests that this constitutes reversible error because it referred to the defendant's failure to testify on his own behalf. We disagree.

The comment in question must be looked at in the context in which it was made. Boyde v. California, 494 U.S. 370, 110 S.Ct. 1190, 108 L.Ed.2d 316 (1990). Boyde v. California, involved a similar situation. The appellant asserted that comments made by the prosecutor immediately before the jury began sentencing deliberations unfairly influenced the jury. The Court stated:

“This is not to say that prosecutorial misrepresentations may never have a decisive effect on the jury, but only that they are not to be judged as having the same force as an instruction from the court. And the arguments of counsel, like the instructions of the court, must be judged in the context in which they are made.” (citations omitted).

Id. 110 S.Ct. at 1200.

In the present case, the prosecuting attorney made several references to the defense counsel's failure to explain the State's evidence. Each of these statements referred to the evidence presented by the defense, not about the defendant's failure to testify. So it was with the comment in question.

The trial court, in an Order Denying Motion for New Trial, found that:

The prosecutor's comment, when viewed by itself, may appear to be improper on the surface, however, when viewed in the entire context and perspective of the trial, and the context of the comment, the Court is firmly of the belief beyond a reasonable doubt that any error was harmless.

This finding was based on several facts. The prosecutor immediately corrected himself after making the statement, during voir dire each juror was told that the defendant did not have to testify and that the burden of proving the defendant's guilt beyond a reasonable doubt was on the State, and the jury was given an instruction that they could not draw any inference of guilt from the defendant's failure to testify, nor could that fact enter into their deliberations in any way. In addition, the trial court offered to reinstruct the jury on the issue of the defendant's failure to testify, but that offer was rejected by defense counsel.

We agree that, taken in context, the statement made by the prosecutor did not pertain to the defendant's failure to testify, but instead was a comment on the sufficiency of the defendant's evidence. It is entirely permissible for the prosecutor to comment on inconsistencies in the evidence presented by the defendant, United States v. Scott, 660 F.2d 1145, cert. denied, 455 U.S. 907, 102 S.Ct. 1252, 71 L.Ed.2d 445 (1982), and to draw inferences from those inconsistencies. United States v. Ellis, 595 F.2d 154, cert. denied, 444 U.S. 838, 100 S.Ct. 75, 62 L.Ed.2d 49 (3rd Cir.1979).

The defense further argues that the trial court impermissibly limited the scope of inquiry into whether the jury was influenced by the prosecutor's comment. The trial court permitted post-trial interviews of the jurors and authorized the defense to hire an investigator for that purpose. Of the fourteen jurors who heard the case, five jurors agreed to be interviewed, two refused, and seven were not contacted before the hearing. The defense requested a postponement of the hearing in order to have time to contact them, but this request was denied. The court also denied defense counsel's request to call some of the jurors as witnesses at the post conviction proceedings, or to take their depositions.