Executed January 27, 2006 1:17 a.m. by Lethal Injection in Indiana

4th murderer executed in U.S. in 2006

1008th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in Indiana in 2006

17th murderer executed in Indiana since 1976

|

|

| Since 1976 |

Date of Execution |

State |

Method |

Murderer

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Date of

Birth |

Victim(s)

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Date of

Murder |

Method of

Murder |

Relationship

to Murderer |

Date of

Sentence |

| 1008 |

01-27-06 |

IN |

Lethal Injection |

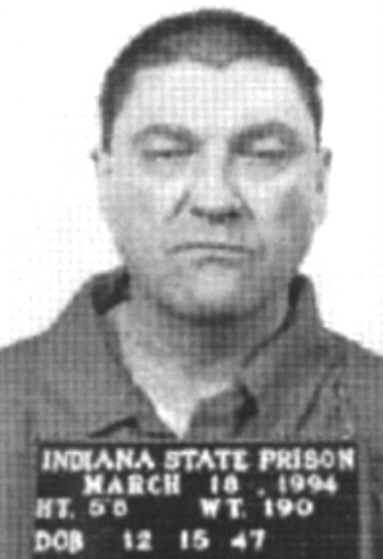

Marvin Bieghler W / M / 33 - 58 |

12-15-47 |

Tommy Miller

W / M / 21

Kimberly Miller

W / F / 19 |

12-10-81 |

Handgun |

Drug Customer

and Wife |

03-25-83 |

Summary:

Summary: Bieghler was in the business of buying and selling marijuana. Tommy Miller sold drugs for Bieghler. After one of Bieghler’s chief operatives was arrested and a large shipment seized, he suspected Miller of “snitching” on him. Bieghler and his bodyguard, Brook, drove to Miller’s trailer near Kokomo, and while his bodyguard waited outside, Bieghler went in and shot both Tommy Miller and his pregnant wife Kimberly with a .38 pistol. A dime was found near each body. He was later arrested in Florida. Brook cut a deal and was the star witness for the State at trial. While the gun was never recovered, nine .38 casings found at the scene matched those found at Bieghler’s regular target shooting range.

Final Meal:

Shrimp, mushrooms and deep-fried onions appetizers, New York strip steak, a chicken breast, baked potato, salad, and 7-Up soft drink.

Final Words:

"Let's get it over with."

Citations:

Direct Appeal:

Bieghler v. State, 481 N.E.2d 78 (Ind. July 31, 1985)

Conviction Affirmed 4-0 DP Affirmed 4-0

Pivarnik Opinion; Givan, Debruler, Prentice concur; Hunter not participating.

Bieghler v. Indiana, 106 S.Ct. 1241 (1986) (Cert. denied).

PCR:

05-25-90 PCR Petition filed; PCR denied by Special Judge Bruce Embrey 03-27-95.

Bieghler v. State, 690 N.E.2d 188 (Ind. 1997)

Affirmed 5-0; Shepard Opinion; Dickson, Sullivan, Selby, Boehm concur.

Bieghler v. Indiana, 112 S.Ct. 2971 (1992) (Cert. denied).

Habeas:

01-20-99 Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus filed in U.S. District Court, Southern District of Indiana.

Judge Larry J. McKinney

07-07-03 Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus denied.

Bieghler v. McBride, 389 F.3d 701 (7th Cir. November 18, 2004) (03-3749).

(Appeal of denial of Habeas Writ)

Affirmed 3-0; Terence T. Evans Opinion; Michael S. Kanne, Ilana Diamond Rovner concur.

For Defendant: Brent Westerfield, Linda Meier Youngcourt, Huron

For State: Stephen R. Creason, Deputy Attorney General (Carter)

Bieghler v. McBride, 126 S.Ct. 430 (October 11, 2005) (Cert. denied)

Internet Sources:

Clark County Prosecuting Attorney

BIEGHLER, MARVIN (ON DEATH ROW SINCE 03-25-83)

DOB: 12-15-1947

DOC#: 13153

White Male

Court: Originally venued to Wabash County; By agreement, returned to Howard County

Trial Judge: Howard County Superior Court Judge Dennis H. Parry

Prosecutor: Richard L. Russell, Charles J. Myers

Defense Attorneys: Charles Scruggs, John C. Wood

Date of Murder: December 10, 1981

Victim(s): Tommy Miller W/M/21 (Drug Customer of Bieghler); Kimberly Miller W/F/19 (Drug Customer's Wife)

Method of Murder: shooting with .38 handgun

Trial: Information/PC for Murder filed (03-30-82); Amended Information for Death Penalty filed (04-12-82); Motion for Speedy Trial (11-29-82); Voir Dire (02-02-83, 02-03-83, 02-04-83, 02-07-83, 02-08-83, 02-09-83, 02-10-83, 02-11-83, 02-12-83 ); Jury Trial (02-14-83, 02-15-83, 02-16-83, 02-17-83, 02-21-83, 02-22-83, 02-23-83, 02-24-83, 02-25-83, 02-28-83); Deliberations 13 hours, 10 minutes; Verdict (03-01-83); DP Trial (03-03-83); Deliberations 11 hours, 55 minutes; Verdict (03-03-83); Court Sentencing (03-25-83).

Conviction: Murder, Murder, Burglary (B Felony)

Sentencing: March 25, 1983 (Death Sentence; no sentence entered for Burglary)

Aggravating Circumstances: b (1) Burglary; b (3); 2 murders

Mitigating Circumstances: None.

Kokomo Tribune

"Bieghler put to death; Indiana man executed for 1981 slayings," by Mike Fletcher. (January 26, 2006 09:08pm)

An admitted drug dealer was put to death early Friday for the 1981 slayings of a man and his pregnant wife inside their home, about an hour after the U.S. Supreme Court cleared the way for his execution.

Marvin Bieghler, 58, was pronounced dead at 2:17 a.m. EST after a lethal injection, state Department of Correction spokeswoman Java Ahmed said. Like a man on Florida's death row, he had challenged the method of execution.

Bieghler's final words were "Let's get it over with," she said.

- - - -

MICHIGAN CITY — A federal appeals court issued a stay of execution Thursday night for Marvin Bieghler just hours before he was to be put to death.

The state attorney general’s office immediately asked the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn the stay so the execution could proceed early today. The situation was ongoing at the Tribune’s press time.

The legal move came after the Supreme Court had turned down Bieghler’s appeal to block his execution for the December 1981 slayings of Tommy and Kimberly Miller, a Russiaville couple.

Kimberly’s brother, John Wright, was anxious to hear Bieghler’s last words.

“This is long overdue,” Wright of Greentown said Wednesday. “I’m looking for closure.”

In 1983, Bieghler was convicted of two counts of murder in an execution-style shooting. He has been on death row in Michigan City for 23 years.

Bieghler had exhausted all of his appeals and was denied clemency Thursday by Gov. Mitch Daniels. His attorneys, Lorinda Youngcourt and Brent Westerfield, continued to fight for his life late into the night Thursday.

Bieghler, like Florida inmate Clarence Hill, challenged the lethal injection process as unconstitutional. Hill contends the three chemicals used in Florida’s method of execution — the same as those used in Indiana — cause pain, making the execution cruel and unusual punishment.

Bieghler was to be injected with sodium pentothal, pancurium bromide and potassium chloride.

Bieghler claimed he was innocent, but told parole board members last Friday, “If I can’t get out, then let’s get it done.”

After hearing from Bieghler and the victims’ families, the parole board unanimously voted Monday to deny clemency.

Kimberly’s family says Bieghler’s execution is long overdue.

“We always had faith in the system,” said Wright.

Wright, who was not expected to attend the execution, testified at Monday’s parole board hearing that he hoped the board would uphold the death penalty.

“Monday was enough for me,” Wright said of reliving what happened to his sister.

“It was like I was the last voice for my sister. We were pretty close. She came over and cut my hair the day before she was murdered.

“It’s a shame. It’s been 20 or more years and it seems like yesterday,” he said. “I’m just hoping this puts closure to it, and I can start breathing better. I’m tired of reading about it and hearing about it. It’s hard to explain.”

There’s no doubt in Wright’s mind the Bieghler was the killer.

“From listening Monday to each of the parole board members, it even made it clearer,” said Wright. “Those people are extremely up on the case. It’s amazing to hear their thoughts. It gave me some assurance that the right thing is being done.”

Tommy Miller’s brother, Kenneth, said the family has had a rough time dealing with the loss.

Kenneth, his mother, Priscilla Hodges, and other family members were expected to attend today’s execution.

Kenneth has only one question for Bieghler.

“I would like to know why. Why did you do it, Marvin?”

The murders

Kenneth Miller discovered the Millers’ bodies at Dec. 11, 1981, in their Russiaville mobile home. Kimberly was five to eight weeks pregnant. The Millers’ then 2-year-old son witnessed their deaths.

Bieghler, an admitted marijuana supplier and dealer in Howard County, was ordered to die by Judge Dennis Parry after jurors convicted him of two counts of murder and recommended the death penalty. According to court documents, Bieghler shot the couple because he was convinced Tommy Miller told police about his drug operation.

He also contended Tommy Miller owed him a drug debt.

Tommy Miller was shot in the chest six times. His wife, who was four to eight weeks pregnant, was shot three times in the chest.

Bieghler dropped a dime on each of the dead bodies, according to court records.

By doing so, authorities said Bieghler was sending a message to other possible informants that snitches die and won’t be tolerated. Authorities said Tommy Miller was not a police informant.

Indianapolis Star

"Indiana inmate executed just minutes after court ruling," by Tom Coyne. (AP January 27, 2006)

MICHIGAN CITY, IND. -- An Indiana inmate was executed early Friday for the 1981 slayings of a Howard County couple, with the lethal injection starting about an hour after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a lower court's order allowing him a new appeal.

The Supreme Court announced its 6-3 decision less than a half hour before the scheduled time of Marvin Bieghler's execution. The late court action caused a delay of about 30 minutes in carrying out the execution.

Bieghler was pronounced dead at 1:17 a.m. CST, after the injection process started about 12:30 a.m., state Department of Correction spokeswoman Java Ahmed said.

His final words were "Let's get it over with," Ahmed said.

The Supreme Court's ruling overturned a federal appeals court decision Thursday night that granted Bieghler, 58, a chance to challenge the legality of lethal injection even though the Supreme Court had rejected a similar appeal just hours earlier.

Gov. Mitch Daniels on Thursday had turned down a clemency request.

Bieghler, an admitted drug dealer, was convicted in the deaths of Tommy Miller, 20, and his pregnant wife, Kimberly Jane Miller, 19, whose bodies were found in their mobile home near Russiaville, about 10 miles west of Kokomo.

Bieghler, like Florida inmate Clarence Hill, challenged lethal injection as unconstitutional. Hill contends the three chemicals used in Florida's method of execution _ the same as those used in Indiana _ cause pain, making his execution cruel and unusual punishment.

The Supreme Court said Wednesday it would hear arguments in Hill's case, with the justices to decide whether a federal appeals court was wrong to prevent Hill from challenging the lethal injection method.

Bieghler's case differed from Hill's because he was allowed to contest the Indiana execution method and lost.

The Supreme Court has never found a specific form of execution to be cruel and unusual, and the Florida case does not give the court that opportunity. The justices could, however, spell out what options are available to inmates with last-minute challenges to the way they will be put to death.

Bieghler's attorney, Brent Westerfeld, told justices in a motion Thursday that a "grave injustice may arise" if Bieghler was executed while Hill's case is pending because there is a chance that Hill will win the right to pursue his claim against lethal injection and eventually win.

The state attorney general's office argued that Bieghler's appeal was a delay tactic and that Indiana's chemical injection method of execution, used since 1996, was constitutional.

The state argued that the Constitution does not guarantee a pain-free execution.

"Indeed, electrocution is a constitutionally permissible form of execution which is undoubtedly more painful than lethal injection," the brief said.

Justices John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer voted to grant the stay, court spokesman Ed Turner said.

About 25 people protested Thursday night against the death penalty outside the prison.

On Monday, the Indiana Parole Board voted unanimously against recommending clemency for Bieghler, and Daniels issued a brief statement Thursday saying he had reviewed Bieghler's petition and rejected it.

Tommy Miller, one of Bieghler's victims, had been shot six times and his wife, who was four weeks pregnant, was shot three times. Bieghler told the parole board last week that he did not kill the couple and wanted Daniels to commute his death sentence to time served.

Bieghler was the sixth Indiana inmate to be executed since Daniels took office just over a year ago. He commuted the death sentence of another inmate to life in prison last year.

Fort Wayne News Sentinel

"Indiana death row actions." (Associated Press Posted on Fri, Jan. 27, 2006)

Six Indiana death row inmates have been executed since Gov. Mitch Daniels took office in January 2005. Last year's five executions were the most since the state re-instituted the death penalty in 1977. Daniels blocked the execution of another condemned inmate:

Executed:

_ Donald Ray Wallace, March 10, 2005, for the 1980 slayings of Patrick and Theresa Gilligan of Evansville and their two children.

_ Bill J. Benefiel, April 21, 2005, for the 1987 torture-slaying of 18-year-old Dolores Wells of Terre Haute.

_ Gregory Scott Johnson, May 25, 2005, for the 1985 beating death of 82-year-old Ruby Hutslar of Anderson during a burglary of her home. Johnson had sought a reprieve from Daniels in order to donate his liver to his sister.

_ Kevin A. Conner, July 27, 2005, for the 1988 murders of three Indianapolis men following an argument.

_ Alan L. Matheney, Sept. 28, 2005, for killing his ex-wife, Lisa Bianco, outside her Mishawaka home in 1989 while he was free from prison on an eight-hour pass.

_ Marvin E. Bieghler, Jan. 27, 2006, for the 1981 shooting deaths of Tommy Miller and his pregnant wife, Kimberly Jane Miller, at their Russiaville home.

Commuted to life in prison:

_ Arthur P. Baird II, convicted for 1985 murders of his wife, who was seven months pregnant, and his parents in Montgomery County, granted clemency by Daniels on Aug. 29, 2005.

Fort Wayne News Sentinel

"Indiana inmate executed quickly after court ruling," by Tom Coyne. (AP Posted on Fri, Jan. 27, 2006)

MICHIGAN CITY, Ind. - Marvin Bieghler's reprieve from death was brief.

The admitted drug dealer who denied killing a Howard County couple 25 years ago died of a lethal injection early Friday, less than 90 minutes after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a lower court's order allowing him a new appeal.

The Supreme Court announced its 6-3 decision less than a half hour before the scheduled time of Marvin Bieghler's execution. The late court action caused Bieghler's execution to delayed about 30 minutes.

Bieghler, 58, who sought the appeal even though he had said he wanted to die if he couldn't gain his release from prison, had a brief final comment: "Let's get it over with."

The Marine Corps veteran who saw significant combat during the Vietnam War also issued a written statement released by the prison. But he did direct the phrase "semper fi" - the Marine Corps motto meaning "always faithful" in Latin - to those he called his "brother warriors."

The brief statement concluded: "I believe in God, country, corps. Death before dishonor. To my son, grandkids and stepkids, you will always have a piece of my heart. Semper fi, Marv."

The Supreme Court's ruling overturned a federal appeals court decision Thursday night that granted Bieghler a chance to challenge the legality of lethal injection even though the Supreme Court had rejected a similar appeal just hours earlier.

Gov. Mitch Daniels on Thursday had turned down a clemency request.

Bieghler was convicted in the deaths of Tommy Miller, 20, and his pregnant wife, Kimberly Jane Miller, 19, whose bodies were found in their mobile home near Russiaville, about 10 miles west of Kokomo.

Tommy Miller's mother, Priscilla Hodges of Kokomo, traveled to the prison but did not witness the execution. Indiana law allows only those invited by the person to be executed to witness the execution. She said she was there to show support her family.

"I still miss my kids. Kim was like my daughter," she said.

She said afterward she felt some sense of relief at the execution but that it did not bring her any closure.

"I still miss my kids. Kim was like my daughter," she said.

Hodges said she hopes Bieghler made peace with God before he died and she hopes he is with God. She still thinks he deserved to die.

"I believe in the death penalty and, yes, I believe Marvin deserved to die," she said. "Because I believe he killed my children."

Bieghler, like Florida inmate Clarence Hill, challenged lethal injection as unconstitutional. Hill contends the three chemicals used in Florida's method of execution - the same as those used in Indiana - cause pain, making his execution cruel and unusual punishment.

The Supreme Court said Wednesday it would hear arguments in Hill's case, with the justices to decide whether a federal appeals court was wrong to prevent Hill from challenging the lethal injection method.

Bieghler's case differed from Hill's because he was allowed to contest the Indiana execution method and lost.

The Supreme Court has never found a specific form of execution to be cruel and unusual, and the Florida case does not give the court that opportunity. The justices could, however, spell out what options are available to inmates with last-minute challenges to the way they will be put to death.

Bieghler's attorney, Brent Westerfeld, told justices in a motion Thursday that a "grave injustice may arise" if Bieghler was executed while Hill's case is pending because there is a chance that Hill will win the right to pursue his claim against lethal injection and eventually win.

P>The state attorney general's office argued that Bieghler's appeal was a delay tactic and that Indiana's chemical injection method of execution, used since 1996, was constitutional.

The state argued that the Constitution does not guarantee a pain-free execution.

"Indeed, electrocution is a constitutionally permissible form of execution which is undoubtedly more painful than lethal injection," the brief said.

Justices John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer voted to grant the stay, court spokesman Ed Turner said.

About 25 people protested Thursday night against the death penalty outside the prison.

WISH-TV

"Death Row Inmate: Let's Get It Over With." (January 27, 2006)

Overnight, the US Supreme Court lifted a stay of execution for Marvin Bieghler, giving the state the go-ahead to put him to death.

Bieghler was convicted in the 1981 deaths of a young Russiaville couple, 20-year-old Tommy Miller and his pregnant wife 19-year-old Kimberly Jane Miller.

Bieghler was executed early Friday morning at 2:17 Indianapolis time at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City. He served 23 years for the crimes and ultimately paid with his own life.

Tommy Miller's family, including his mother, was at the prison during the execution.

"Yes, I believe in the death penalty, and yes, I believe Marvin deserved to die because I believe he killed my children," said Priscilla Hodges.

Bieghler's last words were, "Let's get it over with." This was the first execution of 2006 at the Indiana State Prison.

Before the execution was to take place, a Federal Appeals Court had blocked it. Bieghler's attorney had asked that the execution be delayed until after the US Supreme Court had ruled in a case involving a Florida death row inmate who says lethal injection is cruel and unusual punishment. The state attorney general's office told the court the appeal was just a stall tactic.

ProDeathPenalty.Com

On December 10. 1981, Kenny Miller went to visit his 21-year-old brother, Tommy, who lived with his pregnant 19-year-old wife, Kimberly, in a trailer near Kokomo, Indiana. When he arrived, he discovered a gruesome scene: Tommy and Kimberly had been shot to death, Tommy with six bullets and Kimberly with three. Marvin Bieghler was eventually tried, convicted, and sentenced to death for the two murders in 1983.

The federal appeals court referred to the facts of the crime as senseless. Bieghler was a major drug supplier in Kokomo. He obtained his drugs in Florida and had others, including Tommy Miller, distribute them in the Kokomo area. Several witnesses, including a Bieghler bodyguard, testified that prior to the murders, someone within Bieghler’s drug-dealing operation gave information to the police which led to the arrest of a distributor and the confiscation of some dope. An incensed Bieghler declared repeatedly that when he found out who blew the whistle, he would “blow away” the informant.

Eventually, Bieghler began to suspect that Tommy Miller was the snitch: he told associates that he was going to get him. A major portion of the State’s case rested on the testimony of the bodyguard, who was not prosecuted for his role in the events. According to that testimony, Bieghler and the bodyguard spent the day of the murders drinking beer and getting high on marijuana. During the evening, Bieghler spoke of getting Tommy Miller. Around 10:30 or 11:00 p.m. they left a tavern and drove to Tommy’s trailer. Bieghler got out of the car and went inside carrying an automatic pistol. The bodyguard followed and saw Bieghler pointing the weapon into a room. Bieghler and Brook then ran back to the car and drove away. Later that night, a distraught Bieghler tearfully announced that he was leaving for Florida. Tommy’s and Kimberly’s bullet-ridden bodies were discovered the next morning. Police learned that nine shell casings found at the murder scene matched casings from a remote rural location where Bieghler fired his pistol during target practice. At trial, an expert testified that the two sets of casings were fired from the same gun.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

Do Not Execute Marvin Bieghler!

Marvin Bieghler - January 27, 2006 - Indiana

Marvin Bieghler, a white man, faces execution for the 1981 shooting deaths of Tommy Miller, 20, and his pregnant wife, Kimberly Jane Miller, 19 in Howard County, Indiana. Bieghler, an alleged drug dealer, reportedly believed that Tommy Miller had been the informant who provided police the information that led to the arrest of Bieghler’s supplier, thereby putting Bieghler out of business. Bieghler had said that if discovered he would “blow [the informant] away.”

Bieghler was convicted notwithstanding the contradictory testimony of key witnesses regarding events on the night of the murder. The testimony of Harold K. Brook, Bieghler’s partner and bodyguard, who claims to have been present at the time of the murder, indicated that the murders had to have taken place before 11 p.m. Yet, according to the testimony of Fay Nava, Tommy Miller’s mother, as well as the couple’s landlord and a neighbor, the Millers were alive after 11 p.m. Despite the conflict in testimony, the Indiana Supreme Court denied Bieghler’s appeals. The Court maintained that the discrepancies between the testimonies did not amount to insufficient evidence. It also should be noted that Brook testified against Bieghler after reaching a beneficial deal with the prosecution. Robert Nutt Jr., another of Bieghler’s main distributors, also made a deal with the prosecution to avoid criminal charges in exchange for his testimony against Bieghler.

Bieghler always has maintained his innocence. Moreover, Brooks and Nutt had just as much motive to kill the Millers as Bieghler did. While Brooks and Nutt had incentive to lie about Bieghler’s whereabouts and the time of the murder, there is no reason for the mother of Tommy Miller to say she saw her son after the alleged time of the crime if she did not. Unfortunately, Brooks and Nutt turned State’s witnesses first.

Please write Gov. Mitch Daniels requesting that he stop the execution of Marvin Bieghler!

WTHR-TV

"Execution set, execution stayed, stay lifted, Bieghler executed."

Michigan City, January 27 - An Indiana inmate was executed early Friday for the 1981 slayings of a Howard County couple, with the lethal injection starting about an hour after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a lower court's order allowing him a new appeal.

The Supreme Court announced its 6-3 decision less than a half hour before the scheduled time of Marvin Bieghler's execution. The late court action caused a delay of about 30 minutes in carrying out the execution.

Bieghler was pronounced dead at 1:17 a.m. CST, after the injection process started about 12:30 a.m., state Department of Correction spokeswoman Java Ahmed said.

His final words were "Let's get it over with," Ahmed said.

The Supreme Court's ruling overturned a federal appeals court decision Thursday night that granted Bieghler, 58, a chance to challenge the legality of lethal injection even though the Supreme Court had rejected a similar appeal just hours earlier.

Gov. Mitch Daniels on Thursday had turned down a clemency request.

Bieghler, an admitted drug dealer, was convicted in the deaths of Tommy Miller, 20, and his pregnant wife, Kimberly Jane Miller, 19, whose bodies were found in their mobile home near Russiaville, about 10 miles west of Kokomo.

Bieghler, like Florida inmate Clarence Hill, challenged lethal injection as unconstitutional. Hill contends the three chemicals used in Florida's method of execution - the same as those used in Indiana - cause pain, making his execution cruel and unusual punishment.

The Supreme Court said Wednesday it would hear arguments in Hill's case, with the justices to decide whether a federal appeals court was wrong to prevent Hill from challenging the lethal injection method.

Bieghler's case differed from Hill's because he was allowed to contest the Indiana execution method and lost.

The Supreme Court has never found a specific form of execution to be cruel and unusual, and the Florida case does not give the court that opportunity. The justices could, however, spell out what options are available to inmates with last-minute challenges to the way they will be put to death.

Bieghler's attorney, Brent Westerfeld, told justices in a motion Thursday that a "grave injustice may arise" if Bieghler was executed while Hill's case is pending because there is a chance that Hill will win the right to pursue his claim against lethal injection and eventually win.

The state attorney general's office argued that Bieghler's appeal was a delay tactic and that Indiana's chemical injection method of execution, used since 1996, was constitutional.

The state argued that the Constitution does not guarantee a pain-free execution.

"Indeed, electrocution is a constitutionally permissible form of execution which is undoubtedly more painful than lethal injection," the brief said.

Justices John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer voted to grant the stay, court spokesman Ed Turner said.

About 25 people protested Thursday night against the death penalty outside the prison.

On Monday, the Indiana Parole Board voted unanimously against recommending clemency for Bieghler, and Daniels issued a brief statement Thursday saying he had reviewed Bieghler's petition and rejected it.

Tommy Miller, one of Bieghler's victims, had been shot six times and his wife, who was four weeks pregnant, was shot three times. Bieghler told the parole board last week that he did not kill the couple and wanted Daniels to commute his death sentence to time served.

Bieghler was the sixth Indiana inmate to be executed since Daniels took office just over a year ago. He commuted the death sentence of another inmate to life in prison last year.

WISH-TV

"Condemned inmate appeals for clemency; In petition to Daniels, lawyer says man set to die at midnight for '81 murders is innocent," by Will Higgins. (January 26, 2006)

Marvin Bieghler has exhausted his legal options, and now only the governor can save him.

Bieghler is scheduled to be executed by lethal injection at midnight today at the Indiana State Prison in

Michigan City. He was sentenced to death in 1983 for the 1981 murders of Tommy Miller, 21, and his pregnant wife, 19-year-old Kimberly Jane Miller. The victims were found shot execution-style in their trailer near Russiaville in rural Howard County.

Bieghler, an admitted marijuana dealer, had suspected Tommy Miller told police about his drug operations. Police have said Tommy Miller was not an informant.

In a 23-page clemency petition, Bieghler's lawyer, Brent Westerfeld, insisted Bieghler is innocent and that the only evidence against him is circumstantial. "I know Marvin didn't do it," Westerfeld said.

Bieghler, 58, proclaimed his innocence to the Parole Board last week and said he wanted Gov. Mitch Daniels to commute his sentence to time served. He said that if he didn't get his freedom, he wanted to die.

Bieghler also said he was convicted based on the testimony of others who cut deals to avoid prison sentences.

In the year he has been in office, Daniels has fielded three clemency petitions. He granted one for Arthur Baird II, convicted in the 1985 killings of his parents and pregnant wife but found to be severely mentally ill. Baird is now serving a life sentence without parole.

Since 1977, when the death penalty was reinstated, Indiana has executed 16 people, including five last year. Only in 1939 were there more.

Executions, nationally and in Indiana, began increasing in 1996 after passage of the federal Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act. The law makes it harder for prisoners on Death Row to appeal state Supreme Court rulings in federal court.

Since 1996, Indiana has had 13 executions, compared with just three in the previous 10 years. Nationally, the pace has accelerated, though not as markedly.

But "it's not that Indiana loves the death penalty," said Monica Foster, an attorney who often handles death penalty cases. She said last year's spike resulted from a number of bottlenecked cases coincidentally settling.

She said there also had been a number of death sentence reversals during appeals. There have been five reversals just since June 2004.

At this point, there are 25 men on Indiana's Death Row. One woman, Debra Brown, is sentenced to die in Indiana but is being kept in a prison in Ohio.

Bieghler ordered what is now referred to as a condemned prisoner's "special meal" for his last big meal Wednesday night: shrimp, mushrooms and deep-fried onions appetizers; a New York strip steak and a chicken breast; baked potato; salad; and to drink, 7-Up.

LaPorte Harold Argus

"Bieghler executed; Admitted drug dealer dies after the U.S. Supreme Court overturns appeal," by Dawn shackelford. (January 27, 2006)

MICHIGAN CITY — Marvin Bieghler was executed early this morning, but not before the highest court in the nation weighed in on the decision.

Bieghler, 58, the admitted drug dealer who denied killing a Russiaville man and his pregnant wife 25 years ago, died by lethal injection less than 90 minutes after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a lower court's order allowing him a new appeal.

The Supreme Court announced its 6-3 decision less than a half hour before the scheduled time of Bieghler's execution. The late court action delayed the execution for about 30 minutes.

Bieghler, who sought the last-ditch appeal even though he had said he wanted to die if he couldn't gain his release from prison, had a brief final comment: "Let's get it over with."

The Marine Corps veteran who saw significant combat during the Vietnam War also issued a written statement released by the prison. He directed the phrase "semper fi" — the Marine Corps motto meaning "always faithful" in Latin — to those he called his "brother warriors."

The brief statement concluded: "I believe in God, country, corps. Death before dishonor. To my son, grandkids and stepkids, you will always have a piece of my heart. Semper fi, Marv."

Indiana State Prison spokesman Barry Nothstine told The Herald-Argus around 8 p.m. Thursday that the prison had received word that a federal appeals court had issued a stay of execution. Nothstine said the state attorney general’s office had immediately asked the Supreme Court to overturn the ruling.

“Until we get word from the attorney general’s office, then we have to remain active,” Nothstine explained around 10 p.m. to a crowd of protesters and media correspondents. “I’ve been here 19 years, but this is unusual.”

At 11:45 p.m., 15 minutes before Bieghler was scheduled to die, prison officials received word that the Supreme Court had overturned the lower court’s stay of execution.

In the appeal, Bieghler challenged the lethal injection process as unconstitutional, stating that the three chemicals used cause pain, making the execution cruel and unusual punishment.

The state attorney general’s office said in a brief to the Supreme Court that Bieghler’s appeal was only a delay tactic, arguing that the Constitution doesn’t guarantee a pain-free execution.

“Indeed, electrocution is a constitutionally permissible form of execution which is undoubtedly more painful than lethal injection,” the brief said.

Bieghler died at 1:17 a.m., maintaining his innocence as he had throughout his 23 years of appeals.

Indianapolis Star

"Board recommends against clemency for condemned inmate ," by Ken Kusmer. (Associated Press Writer January 23, 2006 7:32 PM)

INDIANAPOLIS -- The Indiana Parole Board voted unanimously Monday to recommend against clemency for Marvin Bieghler, the self-professed "King Kong of Kokomo" sentenced to death for the execution-style slayings of a Howard County couple in 1981.

Barring a last-minute reprieve from Gov. Mitch Daniels or the courts, Bieghler, 58, is scheduled to die by lethal injection at the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City early Friday.

Bieghler, an admitted marijuana dealer, was convicted of killing Tommy Miller, 20, and Kimberly Jane Miller, 19, whose bodies were found Dec. 11, 1981, in their mobile home near Russiaville. Tommy Miller had been shot six times and his pregnant wife three times.

Authorities contended he killed the couple because he believed Tommy Miller had told police about his operation moving marijuana from Florida to the Kokomo area and also felt Miller owed him a drug debt.

"By his own testimony, Mr. Bieghler stated he was the 'King Kong of Kokomo' in the drug business," Valerie Parker, vice chairwoman of the Parole Board, said, reading her letter to Daniels recommending against clemency.

Board Chairman Raymond Rizzo acknowledged Bieghler was convicted largely on circumstantial evidence, as the condemned prisoner's attorney had argued during the clemency hearing earlier in the day.

"What we have is a convicted double killer, scheduled for execution in less than 96 hours, who also lacks evidence proving his innocence, woven deeply into a sordid saga of marijuana by the bale, money by the cooler-full, guns of every type, and a seemingly endless parade of felons, all of whom seem eager to drop a dime on each other," Rizzo said.

Bieghler had dropped a dime on each of the victims' bodies, according to court records, to send a message to that he would not tolerate informants. Authorities have said Miller was not an informant.

Bieghler told the Parole Board Friday that he was innocent and wanted Daniels to commute his sentence to time served, but that if not granted his freedom, he wanted to die.

"If I can't get out, then let's get at it," he said. "I'm not in here begging for my life. I'm not going to do life without parole for something I didn't do."

Bieghler's attorney, Brent Westerfeld, asked the board to recommend clemency as it had in the case of another death row inmate, Darnell Williams, in 2004. Former Gov. Joe Kernan commuted Williams' sentence to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Others implicated in Bieghler's drug operation cut deals with prosecutors in exchange for the testimony that wound up convicting his client, Westerfeld said.

"The evidence against Marvin was never strong," Westerfeld said. "Police pressured (one witness) to get a story. They made a deal to get a story."

Kimberly Jane Miller's brother, John Wright of Greentown, choked back tears as he testified during Monday's hearing.

"Our family pleads with this board and Gov. Daniels to go through with and uphold this death penalty," Wright said.

The Parole Board also heard the reading of a letter from Tommy Miller's mother, Priscilla Hodges, in which she lamented losing the opportunity to be a grandmother to the slain couple's unborn child.

"This entire family has been victimized by what Marvin Bieghler did for over 20 years," Hodges wrote.

The Parole Board has recommended clemency in a capital case just once since the death penalty was reinstated in Indiana in 1977. Board members unanimously recommended clemency for Williams in 2004, saying his case had too many unresolved questions.

Daniels commuted the death sentence of Arthur Baird II to life without parole last August. Baird's lawyers argued that he was mentally ill, but the state Parole Board voted 3-1 to recommend that the execution be carried out.

It was not clear when Daniels would decide whether to grant clemency to Bieghler. Daniels spokeswoman Jane Jankowski said the governor had received a briefing on the case and was reviewing the information.

Five people have been executed since Daniels took office in January 2005.

Michigan City News Dispatch

"Bieghler has last clemency hearing," by Jason Miller. (January 21, 2006)

During a clemency hearing at the Indiana State Prison on Friday, Marvin Bieghler blamed police, his former bodyguard and his number-one drug distributor for the double murder for which he was sentenced to death in 1983.

The tales of court corruption, dirty police and lying associates the 58-year-old relayed, though, might not make a difference to the Indiana Parole Board.

“We have no ability to investigate. That's not our role,” Parole Board Chairman Raymond Rizzo said Friday. “Our role is the question of clemency. We take everything into consideration, but the ultimate decision is the governor's.”

Bieghler, convicted of killing Tommy Miller and Miller's pregnant wife, Kim, in a Kokomo home in the early 1980s, asked the parole board at his final clemency hearing Friday to set him free.

He's scheduled to be executed in the early morning Jan. 27.

Bieghler asked for a new trial or a release from prison Friday, saying he couldn't spend the rest of his life in prison for a crime he says he didn't commit.

“I'm not here begging you people for my life,” Bieghler said. “Life without parole for something I didn't do ... I'd rather die.

“I'd rather you just put me on that gurney. If I can't get out and go fishing and hunting, the courts can kiss my Marine Corps ass.”

Bieghler was convicted of killing the couple in retribution for what police said was Bieghler's contention that Tommy Miller had turned Bieghler in to police.

Bieghler - who was a middle-man for a Florida-based marijuana business - spent nearly three hours Friday refuting the claim, telling the board his marijuana distributor paid Bieghler's then bodyguard and partner - Harold “Tommy” Brook - to kill the pair.

He claimed the distributor blamed Tommy Miller for “snitching,” leading to the distributor's arrest.

Bieghler said he never dealt with any drug customers except the distributor and added the distributor and Tommy Miller “had a beef” for years.

Bieghler also claimed prosecutors suppressed evidence and that police were involved in drug dealing. He said he possesses information that will prove his innocence.

“I didn't kill those kids,” he said. “I can't get anyone to believe me. I've got proof, but the court said it's irrelevant. It's not irrelevant to me.”

Bieghler sat before the parole board in a red, prison-issue jumpsuit, continually rubbing a raised piece of cloth on his thigh between his thumb and forefinger.

The chain on the shackles that bound his ankles just above the top of his white, New Balance sneakers noisily dropped onto the floor each time he'd raise his legs to stretch.

His attorney, Lorinda Youngcourt, sat next to Bieghler, smiling or turning her head at nearly every word he spoke.

At times Bieghler laughed, as did board members, who jovially commented about the life of a drug dealer and of a former soldier. Bieghler served a combat tour in Vietnam and blamed, in part, that service on his turn toward drugs.

He told members he was a heavy marijuana smoker and had done other drugs in the past.

At the end of Friday's hearing, Bieghler said his 23 years of appeals were likely done.

“If I can't get out, let's just get at it,” he said. “I told the truth. That's all I can do.”

Bieghler v. State, 481 N.E.2d 78 (Ind. July 31, 1985) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was found guilty in the Superior Court, Howard County, Dennis Perry, J., of two counts of intentional murder and one count of burglary. Defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, Pivarnik, J., held that: (1) evidence was sufficient to allow jury to reasonably determine that defendant intentionally killed both victims; (2) evidence was sufficient to prove breaking and entering and to support conviction for burglary; (3) lack of requirement that jury enter written findings to justify death recommendation did not preclude finding that jury had sufficient reason to so recommend and did not prevent Supreme Court from adequately reviewing imposition of death penalty; (4) two jurors who were opposed to death penalty and stated unequivocally that they could not vote for death penalty under any circumstances, were properly excused for cause; (5) coroner was not qualified to give opinion on time of death; (6) arguments as to propriety of certain rulings of trial court concerning admission of certain testimony and physical evidence had been waived; (7) prosecutor did not make any improper remarks during final argument; (8) videotape available to all counsel informed defense counsel as to all items of physical evidence at scene of crime; (9) capital punishment scheme is not unconstitutional; (10) trial court did not commit reversible error by refusing defendant's request for second voir dire of jury after verdicts and before sentencing; (11) defense counsel was not ineffective; and (12) imposition of death penalty was appropriate.

Affirmed; remanded.

PIVARNIK, Justice.

Defendant-Appellant Marvin Bieghler was found guilty by a jury in Howard Superior Court of two counts of intentional murder and one count of burglary. The jury moreover recommended that the death sentence be imposed on both counts of murder. The trial judge found that the jury had properly and lawfully found the death sentence appropriate and accepted the jury's recommendation. The trial judge then imposed the death sentence on Appellant Bieghler. The trial judge did not sentence Bieghler on the burglary conviction.

The facts adduced during Appellant's trial show that at approximately 10:30 a.m. on December 11, 1981, Kenny Miller went to the trailer near Kokomo occupied by his brother, twenty-one year old Tommy Miller, and sister-in-law, nineteen year old Kimberly Miller, and found both of them dead. Kimberly, pregnant with child, was lying in the doorway to their bedroom and Tommy was lying dead at the end of the bed. The evidence also showed that Tommy Miller sold drugs for Appellant and Appellant admitted he was in the business of buying drugs in Florida and selling them in the Kokomo area. One of Appellant's constant companions was his bodyguard, Harold "Scotty" Brook. Brook testified, as did others, that someone had informed the police and caused the arrest of one of Appellant's chief operatives thereby causing the confiscation of a large amount of his marijuana. The expression in the drug culture for informing or "snitching" on an operation is "dropping a dime." Appellant had many times made the statement that if he ever discovered who "dropped a dime" on him, he would "blow him away." It developed that Tommy Miller became suspect as the one who had informed and Appellant many times stated to Brook and other people that he was going to get Miller. Appellant was known to carry an automatic pistol described as a "super .38." On the evening of December 10, 1981, Brook testified that he and Appellant smoked marijuana and drank alcoholic beverages. During this evening, Appellant spoke of getting Tommy Miller. Finally, at around 11:00 p.m., Appellant said, "Let's go," and he and Brook went out to Appellant's automobile. Appellant drove to the neighborhood of Miller's trailer where Brook said he tried to stop Appellant but could not hold him back. Appellant went to the trailer, opened the door and walked to the bedroom door with his pistol in his hand. Brook's testimony equivocated as to whether or not he heard any shots at this time. At one time, he told the police he did hear shots but at another time, and on the witness stand, he said he did not hear any shots. It is not clear whether Brook says none were fired or just that he didn't hear them. Notwithstanding, Brook said that the gun in Appellant's hand was leveled at something in the room and he saw the baby's face with an expression which suggested the baby was crying but he did not hear any cries. Appellant then came out of the room smiling and rushed from the trailer. Appellant later was distraught and crying and said he had to leave town immediately. He very shortly left for Florida.

Eighteen issues are alleged and presented for our review in this direct appeal as follows:

1. insufficiency of the evidence;

2. failure of Indiana's capital punishment scheme to require written findings by the jury;

3. improper jury selection;

4. denial of Appellant's motion for an increased number of peremptory jury challenges;

5. exclusion of the coroner's testimony as to time of death;

6. improper evidentiary rulings;

7. prosecutorial misconduct;

8. improper cross-examination of Appellant;

9. granting of a motion in limine concerning testimony of witness Brook;

10. failure to bring Appellant to trial within 120 days of his extradition;

11. improper discovery by State;

12. improper vesting of power in the prosecutor to elect who should receive the death penalty;

13. improper guidelines for the sentencing trial judge;

14. no meaningful and sufficient appellate review afforded one receiving the death penalty;

15. improper scheme by which death penalties can be initiated by information rather than indictment;

16. denial of Appellant's motion to re-voir dire the jury between the guilt and penalty phases of his trial;

17. modification of Appellant's tendered instruction No. 30 and trial court's refusal to give certain other instructions tendered by Appellant; and

18. incompetency of counsel.

I

Appellant first claims that the State's evidence was insufficient to convict him in that the State failed to prove that the alleged crimes occurred during the period of time specified in the State's response to his notice of alibi. The State's response indicated that it intended to prove Appellant committed the alleged crimes between 10:30 p.m. and 1:00 a.m. during the night of December 10-11, 1981. Appellant's argument is based on the fact that there apparently is a conflict of evidence regarding the time these crimes occurred. In a sufficiency question, of course, this Court will not reweigh the evidence nor judge the credibility of witnesses. We consider only that evidence most favorable to the State together with all reasonable inferences to be drawn therefrom. If there is substantial evidence of probative value to support the conclusion of the trier of fact, even though there is some conflict in that testimony, the verdict will not be overturned. Fielden v. State, (1982) Ind., 437 N.E.2d 986. This is because the resolution of conflicts in the evidence is within the province of the jury.

Brook testified that he spent the evening with Appellant, leaving a tavern around 11:00 p.m. He stated that after Appellant murdered the Millers, they picked up Appellant's girlfriend, Thelma McVety, from her work by 11:15 p.m. McVety said she left her work area at a few minutes after 11:00 p.m. expecting to be immediately picked up by Appellant. There was testimony from McVety and a co-worker that McVety became upset because Appellant was late. McVety testified that she was picked up by Appellant between 11:15 and 11:20 p.m. Fay Nova, Tommy Miller's mother, testified that she talked to Miller at about 11:20 p.m. Appellant's argument is that considering the testimony of Nova and McVety, Tommy Miller would still have been alive after the time that Brook said he and Appellant were at the trailer. Therefore, Appellant's argument follows, Brook's testimony that Appellant murdered the Millers shortly after 11:00 p.m. cannot be believed. An examination of all of the testimony of these witnesses, however, shows that none of them testified with any particular accuracy. Instead, each spoke generally of the time sequences involved but did not indicate that they looked at a watch or compared the time with that of some other incident which would exactly fix the time of each event. Whatever the case, the variance of time suggested by the testimonies of all of these witnesses amounts to no more than fifteen or twenty minutes. The jury could reasonably find that none of the witnesses was testifying about an exact minute and thereby could have resolved all of their testimony in that manner. This alleged conflict therefore does not amount to insufficiency of the evidence warranting reversal but rather amounts to a minor conflict in the evidence that we will not disturb on appeal.

Appellant further claims insufficiency of the evidence with regard to the only eyewitness, Scotty Brook. Appellant first attacks Brook's testimony as lacking credibility due to his character and his testimony that he was drinking alcohol and ingesting marijuana on the night in question. Questions about the character or sobriety of a witness, of course, go to the weight of that witness' testimony and not to its admissibility. Only when certain testimony is inherently improbable or coerced, equivocal, wholly uncorroborated, or of incredible dubiosity, will the appellate court impinge on the jury's prerogative of decision. Rodgers v. State, (1981) Ind., 422 N.E.2d 1211. No such inherent improbability appears in Brook's testimony.

Appellant also claims that Brook's testimony does no more than show that Appellant was present at the victims' trailer and had an opportunity to commit these crimes. He cites us to Glover v. State, (1970) 253 Ind. 536, 255 N.E.2d 657 [Justices Givan and Arterburn dissenting] and Manlove v. State, (1968) 250 Ind. 70, 232 N.E.2d 874, reh. denied 250 Ind. 70, 235 N.E.2d 62. In Manlove, the defendant and the deceased were seen together in public leaving a tavern and the deceased subsequently was found dead in a canal about twelve hours later. There was no evidence that the defendant was near the canal or at the scene of the crime during the time of its commission and the evidence therefore was found insufficient. In Glover, the evidence showed only that the defendant was in the general area of the crime: on a public street near a crowded tavern and on a natural route to the parking lot. Some scuffle had been witnessed between the defendant and the deceased earlier but no one put him at the actual scene of the crime. The court accordingly found no evidence from which a reasonable jury could infer that the defendant stabbed the victim and therefore reversed the conviction. In this case, however, Brook testified that he accompanied Appellant to the trailer with Appellant stating his intent to kill Miller. When the bodies were found the next morning at 10:30, some rigor mortis had set in indicating the victims had been dead for some time although the pathologist, Dr. Pless, said it was impossible to determine the exact time of death. Brook testified that Appellant had with him at the crime scene his super .38 caliber pistol. Shell casings found at the scene were of the super .38 variety as were the slugs found in the bodies of the victims and in the woodwork of the room. Brook's only equivocation was that he did not hear any shots. He did not explain whether he meant no shots were fired or whether he just didn't hear them. His description of the scene indicated that Appellant fired his pistol but Brook said he could not recall hearing sounds, including the baby crying. A dime was found near the body of each victim which was considered significant since Appellant was known to talk about someone "dropping a dime" on him. Appellant told Brook and many others that he intended to "blow [Miller] away" and also told Brook when they headed toward the trailer that he was going to do it then. His subsequent actions in being distraught and in immediately leaving the area further confirmed this. Brook's testimony therefore did more than simply place Appellant at or near the scene of the crime. Accordingly, we find sufficient evidence from which the jury could reasonably determine that Appellant intentionally killed both of the Millers.

Appellant further claims that there was not sufficient evidence to find him guilty of burglary. Ind.Code § 35-43-2-1 (Burns 1985) dictates that to prove a burglary requires the showing of a breaking and entering of the building or structure of another person with intent to commit a felony therein. The evidence above clearly establishes that Appellant entered the Millers' trailer with an intent to kill the Millers. There need not be a showing of actual fracturing or of some physical damage to an entryway in order for there to be an illegal entry. Brook testified that Appellant put his hand in his jacket pocket and gripped the doorknob through his jacket so as not to leave fingerprints. He then simply turned the knob and opened the door, indicating that the door was not locked. This was sufficient to prove a breaking and entering.

* * *

Having disposed of all of the issues raised by Appellant we now review the propriety of the death penalty in Appellant's case pursuant to our responsibility to do so. An examination of the record of this cause clearly supports the conclusion of the trial court that the imposition of the death penalty was appropriate considering the nature of the offense and the character of the defendant. The trial judge made very detailed findings and demonstrated his reasons for coming to the judgment he did. Appellant was upset when he concluded that Miller had informed on him causing him to lose a great deal of his drug supplies and placing him in jeopardy because he was not able to pay the considerable debts he owed to his Florida suppliers. Appellant openly expressed an intent to "blow [Miller] away" and obtained the weapon to do so. The facts amply demonstrated beyond a reasonable doubt that Appellant killed both the Millers in their bedroom with that weapon. The trial court found that the Millers were murdered in execution style since each was shot while standing and then again while lying on the floor of their bedroom; whether either was conscious or unconscious, we shall never know. They were shot several times and the angle of trajectory indicates the person who did the shooting was standing directly above each victim. This is not a case of a shooting involving a burglar who was surprised while burglarizing a home. The facts established that Appellant entered the house trailer in the manner of a classical burglary but with a state of mind bent upon liquidating the occupants. The trial court then found that the State had proved beyond a reasonable doubt the aggravating circumstances and carefully reviewed all potential mitigating circumstances finding that the mitigating circumstances did not in any way affect the conclusions mandated by the aggravating circumstances. The trial court found the jury recommendation to be proper and lawful and accepted that recommendation and imposed the death penalty. The trial court fully complied with the proper procedures mandated in the statute and case law on this subject and we find that the imposition of death recommended by the jury and imposed by the trial court was not arbitrarily or capriciously arrived at and is reasonable and appropriate considering the nature of this offense and the character of this offender.

We affirm the trial court in its judgment including its imposition of the death penalty. This cause is remanded to the trial court for the sole purpose of setting a date for the death sentence to be carried out.

GIVAN, C.J., and DeBRULER and PRENTICE, JJ., concur.

HUNTER, J., not participating.

Bieghler v. State, 690 N.E.2d 188 (Ind. 1997) (PCR)

After his murder convictions and sentence of death were affirmed, 481 N.E.2d 78, defendant petitioned for postconviction relief. The Howard Superior Court, Bruce C. Embrey, Special Judge, denied relief, and defendant appealed. The Supreme Court, Shepard, C.J., held that: (1) defendant did not receive ineffective assistance on direct appeal or at trial; (2) instructions on accomplice testimony and reasonable doubt were proper; and (3) reading of Bible by juror during sequestration did not deprive defendant of fair trial.

Affirmed.

SHEPARD, Chief Justice.

Marvin Bieghler appeals the denial of post-conviction relief concerning his 1983 conviction and death sentence for the murders of Tommy Miller and his pregnant wife, Kimberly. Bieghler raised eighteen claims in his direct appeal, and this Court affirmed in all respects. Bieghler v. State, 481 N.E.2d 78 (Ind.1985).

On post-conviction, Bieghler raises a collection of claims under the rubric of seven arguments:

I. Ineffective assistance of appellate counsel in his direct appeal;

II. Ineffective assistance of counsel at trial;

III. Improper instruction on accomplice testimony;

IV. Error in the jury instructions;

V. Improper jury selection and jury misconduct;

VI. Cumulative error during the penalty phase, rendering his death sentence unreliable; and

VII. Constitutionality of capital sentencing statute.

We affirm the post-conviction court.

Facts

Tommy and Kimberly Miller were found dead in the bedroom of their trailer on the morning of December 11, 1981. Tommy Miller sold marijuana supplied to him by Bieghler, who was a marijuana "wholesaler" in the greater Kokomo area. The couple had been shot with nine rounds from an automatic .38 calibre pistol at point-blank range. A dime was found near each body.

Harold "Scotty" Brook was Bieghler's partner in his marijuana business, accompanying Bieghler on numerous occasions to Florida where Bieghler received large quantities of the drug for transportation back to Kokomo. Brook and others testified that someone had "dropped a dime" on one of Bieghler's main distributors (i.e., informed the police on him) resulting in the distributor's arrest and the confiscation of a large amount of marijuana "fronted" to him by Bieghler. This loss effectively put Bieghler out of business. The witnesses testified that Bieghler repeatedly declared he would "blow away" whoever had "dropped a dime" on his distributor. According to Brook, after Tommy Miller became the suspected "snitch," Bieghler stated on many occasions that he would get Miller.

Brook, who cut a beneficial deal with the prosecutor on unrelated charges in exchange for his testimony, testified that he and Bieghler spent the afternoon and evening of December 10, 1981, drinking beer and smoking marijuana. They eventually wound up at a bar in Galveston, Indiana, a small town in the southeast corner of Cass county. At around 10:30 p.m. Brook, Bieghler, and Brook's brother Bobby John left the bar and traveled to the Millers' trailer, which was located in a rural part of southwestern Howard county near Russiaville. Bieghler parked down the road from the trailer, walked across a field and entered. Brook was following. Upon entering the darkened trailer, Brook saw Bieghler, standing, pointing his "super .38" into one of the rooms. Brook claims he did not hear anything while in the trailer, neither gunshots nor the cry of the Millers' small child who Brook saw standing up in his nearby crib with a crying expression on his face.

Bieghler ran out of the trailer and back to the car with Brook in tow. The group proceeded to Kokomo where they picked up Bieghler's girlfriend, Thelma McVety, from work at around 11:10--11:15 p.m. After dropping McVety off at her house, Brook, his brother, and Bieghler went to the Dolphin Tavern in Kokomo, arriving at 11:30 p.m. Brook and Bieghler then went back to McVety's, where Bieghler tearfully told her that he had to go to Florida, and then left for Florida alone.

Bieghler's "super .38" was never introduced at trial, but nine shell casings found at the murder scene matched casings found at a remote rural location where Bieghler fired his gun for target practice. An expert testified that the two sets of casings were fired from the same gun, which had to have been one of only three types of automatic .38 calibre pistols, one of which was the "super .38."

Bieghler's trial counsel vigorously argued that Bieghler could not have committed the crimes during the time Brook testified the pair went to the Millers' trailer. He called several witnesses who testified about the extremely hazardous, icy road conditions around the Miller trailer that night which would have prevented a round trip from Galveston, to the trailer, and then to McVety's workplace in forty-five minutes. He also called several witnesses who said they spoke with Tommy Miller on the phone that evening after 11 p.m. Nevertheless, the jury found Bieghler guilty of two counts of murder and one of burglary, and recommended the death penalty. The trial judge sentenced Bieghler to death for the murders, but did not sentence him for the burglary.

* * *

Trial Counsel's Performance. Specifically, Bieghler claims that although appellate counsel raised this issue and discussed seven separate instances in support of it, appellate counsel did not argue some of them well, and there were other examples appellate counsel should have raised and argued.

For example, Bieghler says Scruggs should have objected to testimony concerning Bieghler's character and prior bad acts. Appellate counsel did allude to two types of "prior bad act" evidence elicited by the prosecutor to which trial counsel failed to object: evidence about Bieghler's drug-dealing business, and evidence of Bieghler's drug-using lifestyle. While appellate counsel forcefully argued that the prosecution's impermissible use of this evidence throughout the entire trial significantly prejudiced Bieghler, he did not provide examples from or citation to the record in support of this claim. (See P.C.R. at 4618, Br. at 58-59, 102-105.) The State's brief, in addressing this allegation, focussed on the prosecution's admission of evidence pertaining to Bieghler's drug-dealing business and correctly argued that such information was admissible as pertaining to motive, and trial counsel was thus not ineffective for failing to object to its admission or argue for its limitation.

The other line of prosecutorial questions on Bieghler's drug- using lifestyle was not addressed by the State as part of its IAC rebuttal. Likewise, our opinion only addresses this claim of ineffectiveness in terms of evidence admitted to show Bieghler's drug-dealing business and related activities, and does not mention the admission of evidence about Bieghler's drug-using lifestyle and habits. See Bieghler, 481 N.E.2d at 97.

The prosecution questioned a number of witnesses about their personal experience with taking different types of drugs, the effects the different drugs had on them, with taking drugs with Bieghler, and the observed effects drugs had on him, (Nutt, see T.R. at 2354, 2356, 2358-60, 2387; Brook, see T.R. at 2679-85, 2729-2731). After laying this foundation regarding Bieghler's drug habit and the effects that the drugs normally had on Bieghler prior to December 10, 1981, the prosecutor asked Scotty Brook about the events of December 10th. Much of this inquiry centered around when, what type, and how many drugs the two consumed that entire day. (See T.R. at 2371, 2733-37.) The prosecution's questioning of Bieghler followed much the same pattern. (See T.R. at 3052, 3083-86.)

This testimony was elicited in an attempt to establish Bieghler's probable state of mind on the night of the murder, as exemplified by its use in the State's closing argument. For instance, Bieghler admitted smoking marijuana and drinking around fifteen beers the afternoon of the murders, (T.R. at 3020- 3024), and the prosecutor argued, "Bobby Nutt said that he'd seen Marvin Bieghler mix alcohol and marijuana and he said when he did that Marvin Bieghler was wild-like and obnoxious," (T.R. at 3132-33). Addressing the defense argument that Bieghler could not have driven fast on the slick, icy roads, the prosecutor argued,

They were drunk. They were high all day. They were drinking all night. They were taking pills. They were intoxicated.... How many times have you been driving down the highway on an icy road and have some idiot whiz by you like you were standing still? Ice doesn't stop everybody from driving fast. It stops people that have any sense about them from driving fast. Think it would stop a drunk? An intoxicated high person? Total disregard for everything, I would say, the state of his mind that night, the Defendant.

(T.R. at 3152-53.)

Finally, as to what might have finally pushed Bieghler into committing the murders, the State argued,

Do you remember what Scotty Brook said right before they left the Tavern, Dusty's? He said something that went like this, "I'm tired of hearing about it. If you're going to do something, do it, or quit talking about it." This is at a time when this man's got fifteen plus beers, he's high on marijuana, he's taking speed and some other pills we don't know about. I suggest he was mad, said, "All right. I'll show you. I can do it. Let's get in the car. Come on." And in a rage he drove out there and did it.

(T.R. at 3218.) Bieghler's drug use and the effect it potentially had on him the night of the murders was central to understanding his state of mind at that time and explaining some of his alleged actions. Thus, the evidence was relevant, and its relevance was not outweighed by the potential unfair prejudice it engendered against Bieghler. In fact, both the State and the defense found this evidence useful. Much of Bieghler's testimony about his personal drug use was elicited by his trial counsel. (See T.R. at 3003- 04, 3021, 3024.) Then, in his closing argument, defense counsel argued that Bieghler could not have committed the murders because of his intoxicated state:

Scotty says that they left on the county road and drove straight across 22 at sixty miles per hour and the evidence is there was ice everywhere. Marvin's had fifteen to seventeen beers.... How do you explain the fact that they drove from Galveston to Dusty's Tavern to the scene of this crime in twenty minutes in the intoxicated condition that the defendant was in without crashing, when Scott Pitcher crashed at twenty miles an hour. Same roads.

(T.R. at 3181, 3183.) He also argued that Bieghler's intoxicated state would have impaired his shooting ability: "Nine shots were fired and every one of them found their mark. In a dark trailer? By someone as drunk as he's supposed to have been?" (T.R. at 3189.) Thus, both sides saw the relevance of this evidence as it pertained to their versions of the case. Given this, and trial counsel's strategy of complete candor, it was not unreasonable for trial counsel to let it come in, and appellate counsel should not be faulted for failing to cite this evidence in support of his ineffectiveness claim.

On the other hand, we see a colorable argument regarding some of the State's questioning of Bieghler, of his girlfriend's daughter, Theresa McVety, and the State's use of this evidence in its closing argument. The evidence suggested that Bieghler was pretty casual about marijuana use by teenagers, including Theresa's.

By its own admission, the State was trying to show Bieghler's disregard for the law as it pertained to kids and marijuana, an issue with no relevance to proving whether he murdered the Millers. The State was clearly attempting to use Bieghler's prior bad acts to paint him as an immoral miscreant exceedingly different from the jurors, a pariah that should be eliminated from the jurors' community for being "unworthy of membership [in] the human race,"

* * *

Thorough post-conviction review of the proceedings leading to Marvin Bieghler's conviction and sentence reveals no constitutional error by the trial court or in the performance of counsel either at trial or in his direct appeal. In addition, no reversible error has been found in the proceedings of the post-conviction court. The conviction and sentence of death are affirmed.

DICKSON, SULLIVAN, SELBY and BOEHM, JJ., concur.

Bieghler v. McBride, 389 F.3d 701 (7th Cir. November 18, 2004) (Habeas)

Background: Following affirmance of his murder conviction and death sentence on direct appeal, 481 N.E.2d 78, and denial of state postconviction relief, 690 N.E.2d 188, petitioner sought writ of habeas corpus. The United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, Larry J. McKinney, J., denied relief, and petitioner appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals, Terence T. Evans, Circuit Judge, held that:

(1) prosecutor did not impermissibly comment on defendant's post-arrest silence in violation of due process, and

(2) state appellate court did not unreasonably apply federal law in rejecting ineffective assistance of counsel claims.

Affirmed.

TERENCE T. EVANS, Circuit Judge.

Twenty-three years ago, Kenny Miller went to visit his 21-year-old brother, Tommy, who lived with his pregnant 19-year-old wife, Kimberly, in a trailer near Kokomo, Indiana. When he arrived, he discovered a gruesome scene: Tommy and Kimberly had been shot to death, Tommy with six bullets and Kimberly with three. Marvin Bieghler was eventually tried, convicted, and sentenced to death for the two murders in 1983. His convictions and death sentence were upheld by the Indiana Supreme Court, both on direct appeal 2 years later, Bieghler v. Indiana, 481 N.E.2d 78 (Ind.1985), and 12 years after that on appeal from the denial of a petition for postconviction relief, Bieghler v. Indiana, 690 N.E.2d 188 (Ind.1997). Bieghler moved to federal court in 1998 and is here today appealing the district court's denial of his petition for a writ of habeas corpus brought pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2254.

First, the senseless facts as determined by the state courts, which we accept as true on this collateral review. Bieghler was a major drug supplier in Kokomo. He obtained his drugs in Florida and had others, including Tommy Miller, distribute them in the Kokomo area. Several witnesses, including a Bieghler bodyguard named Harold “Scotty” Brook, testified that prior to the murders, someone within Bieghler's drug-dealing operation gave information to the police which led to the arrest of a distributor and the confiscation of some dope. An incensed Bieghler declared repeatedly that when he found out who blew the whistle, he would “blow away” the informant. Eventually, Bieghler began to suspect that Tommy Miller was the snitch: he told associates that he was going to get him.

A major portion of the State's case rested on the testimony of Brook, who was not prosecuted for his role in the events. According to that testimony, Bieghler and Brook spent the day of the murders drinking beer and getting high on marijuana. During the evening, Bieghler spoke of getting Tommy Miller. Around 10:30 or 11:00 p.m. they left a tavern and drove to Tommy's trailer. Bieghler got out of the car and went inside carrying an automatic pistol. Brook followed and saw Bieghler pointing the weapon into a room. Bieghler and Brook then ran back to the car and drove away. Later that night, a distraught Bieghler tearfully announced that he was leaving for Florida. Tommy's and Kimberly's bullet-ridden bodies were discovered the next morning. Police learned that nine shell casings found at the murder scene matched casings from a remote rural location where Bieghler fired his pistol during target practice. At trial, an expert testified that the two sets of casings were fired from the same gun.

Bieghler contends that the prosecution violated his due process rights by exploiting, at trial, his failure to talk to the police after his arrest. He also claims that he was denied effective assistance of counsel. Because Bieghler's petition was filed after April 24, 1996, the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA) governs our analysis. Under the AEDPA, a federal court may not grant a writ unless a final state court decision in the case was “contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States,”28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(1), or was “based on an unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the evidence presented in the State court proceeding,” id. § 2254(d)(2). A state court decision is “contrary to” established Supreme Court precedent when the state court reaches a legal conclusion opposite to that of the Court or decides a case differently than the Court despite “materially indistinguishable facts.” Williams v. Taylor, 529 U.S. 362, 413, 120 S.Ct. 1495, 146 L.Ed.2d 389 (2000). An “unreasonable application” of Supreme Court precedent occurs when the state court identified the correct rule of law but applied it unreasonably to the facts. Id.

According to Bieghler, the prosecution, during its cross-examination of him and again during closing argument, exploited the fact that, after being advised of his Miranda rights, he elected to remain silent and not give arresting officers the version of the night's events he related on the witness stand. If so, this was a constitutionally impermissible tactic under Doyle v. Ohio, 426 U.S. 610, 96 S.Ct. 2240, 49 L.Ed.2d 91 (1976). As applicable here, Doyle holds that the prosecution violates a defendant's due process rights when it uses post-arrest silence to impeach an exculpatory story told at trial. See United States v. Shue, 766 F.2d 1122 (7th Cir.1985). This is so because it is fundamentally unfair to assure a defendant, with Miranda warnings, that his silence will not be used against him, and then turn around and do exactly that.

Bieghler cites several references by the prosecutor to his post-arrest, post- Miranda-warning silence. His trial counsel, however, did not object to these references and therefore forfeited subsequent challenges to them. E.g., United States v. Jacques, 345 F.3d 960, 962 (7th Cir.2003). Ordinarily, when a claimed error is forfeited, we only analyze whether the trial court plainly erred by allowing the prosecutor's comments. Id. But here we evaluate Bieghler's claim “without the screen of the plain error standard” because the State has not argued that it applies. United States v. Cotnam, 88 F.3d 487, 498 n. 12 (7th Cir.1996) (internal quotations omitted); United States v. Leichtnam, 948 F.2d 370, 375 (7th Cir.1991).

At trial, Bieghler took the stand and denied complicity in the murders. He testified about being at other places with other people when the Millers were killed. On this appeal, he complains about several questions put to him by the state's attorney during cross-examination. The prosecutor asked: “[P]rior to the beginning of this trial, did you ever tell the story that you've told today to anyone besides your attorneys?”, “Were you ever given any opportunity to tell the story to anyone?”, and “Did you give it?” In response to the last question, Bieghler answered, “No, I exercised my Miranda rights.” The prosecutor then asked three questions concerning Bieghler's understanding of his Miranda rights before moving on to another subject. It is the State's contention that no reference was made to Bieghler's silence. He was merely fairly cross-examined, says the State, about his direct testimony for the purpose of testing his credibility as a witness.

In an argument that's a little hard to follow, Bieghler contends that this snippet from the prosecutor's closing remarks to the jury ran afoul of the rule announced in Doyle:

Kenny Cockrell's the one that took the Fifth. Kenny Cockrell's the one that wouldn't answer when I asked if he was doing something to Bobby Nutt because a deal went bad. He took the Fifth. Didn't want to be discriminated against. I'm growing to hate that train. As a matter of fact, that train came by during my examination of the Defendant. I don't know, maybe it was my imagination, maybe I wanted to see it, but did you see him, about right before the train came by started to get, his voice was a little different about the time when he left Dusty's? You can talk about that. Maybe I only saw it because I wanted to.

A little later, Bieghler sees error in this statement from the prosecutor's closing argument:

The Defendant denies that he was there. And even though it's not testimony, looking through it in the opening statement, [Defense Counsel] Mr. Scruggs said that he, the Defendant went there that night to Bobby Nutt's. Now the only person that's important to me is, I was looking, I was listening, waiting to hear so that I would know what the Defendant was going to say. You know, I didn't hear him until he sat up here, and you heard him just like I did. He had everything I had but I could never talk to him. I couldn't use prior inconsistent statements to impeach him because I didn't have any. He never said anything ····