2nd murderer executed in U.S. in 2005

946th murderer executed in U.S. since 1976

1st murderer executed in California in 2005

11th murderer executed in California since 1976

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder-Execution) |

Birth |

(Race/Sex/Age at Murder) |

Murder |

Murder |

to Murderer |

Sentence |

||||

| |

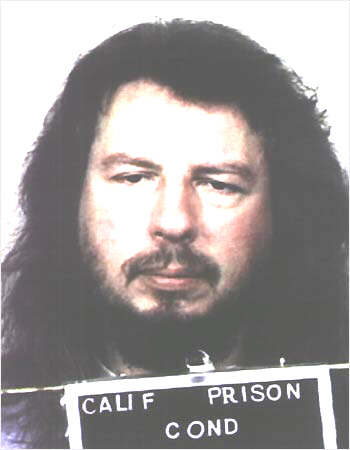

Donald Jay Beardslee W / M / 37 - 61 |

Patty Geddling W / F / 23 Stacey Benjamin W / F / 19 |

Cut Throat with Knife |

Summary:

In 1969, Beardslee killed a 52-year-old woman he met in a St. Louis bar, stabbing her in the throat with a knife and leaving her in a bathtub to bleed to death. After serving seven years of an 18-year sentence in that killing, the former Air Force mechanic moved to California to be near his mother.

In 1981, Beardslee picked up a hitchhiker, Rickie Soria, a drug addict and prostitute. Moving in with Beardslee, Soria introduced him to her friends. One of them, 19-year-old Bill Forrester, claimed that he had been ripped off in a $185 drug deal involving 23 year old Patty Geddling and 19 year old Stacey Benjamin. Frank Rutherford, a drug dealer portrayed as the group's ringleader, devised a scheme to entice Geddling and Benjamin to Beardslee's apartment. The day before, Beardslee sent Soria to buy duct tape to tie the women's hands when they arrived.

After Rutherford accidentally wounded Geddling, Beardslee, Soria and Forrester drove her to a remote site in San Mateo County, where Beardslee shot the young mother twice in the head with a sawed-off shotgun. The next day, Beardslee, Soria and Rutherford, who had remained with Benjamin, used cocaine as they drove 100 miles to a secluded area in Lake County, north of San Francisco. After the two men unsuccessfully strangled Benjamin with a wire garrote, Beardslee slit her throat with Rutherford's knife. Before leaving the body, the two men pulled down Benjamin's pants to make it appear that she had been raped.

Police tracked down Beardslee using a phone number found at one of the crime scenes. As he had in Missouri, Beardslee quickly confessed to the crimes and was the lead witness in the trials. Rutherford, who died in prison two years ago, and Soria were given long prison terms while Forrester was acquitted.

Citations:

People v. Beardslee, 279 Cal.Rptr. 276 (Cal. Mar 25, 1991) (Direct Appeal)

Beardslee v. Woodford, 358 F.3d 560 (9th Cir. January 28, 2004) (Habeas)

Final Meal:

Beardslee refused a special final meal and was offered the same meal as other inmates of chili, macaroni, mixed vegetables, salad and cake, which he declined.

Final Words:

None.

Internet Sources:

California Department of Corrections

ATTENTION PARENTS: The following crime summary contains a graphic description of one or more murders and may not be suitable for all ages.

Beardslee, Donald (CDC #C-82702)

Date Received: 03-14-84

Date of Birth: 05-13-43

Location: San Quentin

Marital Status: Single

County of Trial: San Mateo

Offense Date: 04-25-81

Date of Sentence: 03-12-84

Victims: Patty Geddling, Stacie Benjamin

Co-Defendant: None.

Summary: Donald Beardslee was convicted of First Degree Murder in the deaths of two young women, Patty Geddling and Stacie Benjamin, on April 25, 1981, in an apparent drug-related murder. At the time of the murders, Beardslee was on parole for murder in Missouri.

For Immediate Release

December 17, 2004

Contact: (916) 445-4950

MEDIA ACCESS FOR SCHEDULED EXECUTION

The execution of Donald Beardslee, convicted of one count of first degree murder in the deaths of two women, is set by court order for January 19, 2005, at San Quentin State Prison.

Access Inquiries: Direct all requests and inquiries regarding access to San Quentin State Prison to the California Department of Corrections Communications Office in Sacramento, which is responsible for all media credentials. Requests are due by Friday, January 7, 2005. (See “Credentials.”)

Reporters: Up to 125 news media representatives may be admitted to the Media Center Building at San Quentin to attend news briefings and a news conference after the execution. To accommodate as many media firms as possible, each news media organization applying will be limited to one representative. Firms selected to send a news reporter to witness the execution will be allowed a separate representative at the media center.

Audio/Visual/Still Photographs: In anticipation that interest may exceed space, pool arrangements may be necessary for audio/visual feeds and still photographs from inside the media center. The pool will be limited to two (2) television camera operators, two (2) still photographers, and one (1) audio engineer. The Northern California Radio Television News Directors Association and the Radio Television News Association in Southern California arrange the pool.

Live Broadcasts: On-grounds parking is limited. Television and radio stations are limited to one (1) satellite or microwave vehicle.

Television Technicians: Television technicians or microwave broadcast vehicles will be permitted three (3) support personnel: engineer, camera operator, and producer.

Radio Technicians: Radio broadcast vehicles will be allowed two (2) support personnel: engineer and producer.

Credentials: For media credentials, send a written request signed by the news department manager on company letterhead with the name(s) of the proposed representatives, their dates of birth, driver’s license number and expiration date, social security number, and size of vehicle for live broadcast purposes to:

CDC Communications Office

1515 S Street, Room 113 South

P.O. Box 942883

Sacramento, CA 94283-0001

All written requests must be received no later than Friday, January 7, 2005. Media witnesses will selected from the requests received by that time. Telephone requests will NOT be accepted. Security clearances are required for each individual applying for access to San Quentin. The clearance process will begin after the application deadline. No assurances can be provided that security clearances for the requests, including personnel substitutions, received after the filing period closes January 7, 2005, will be completed in time to permit access to the prison on January 18, 2005.

Facilities: The media center has 60-amp electrical service with a limited number of outlets. There are several pay telephones. Media orders for private telephone hookups must be arranged with SBC. SBC will coordinate the actual installation with San Quentin. There is one soft drink vending machine at the media center. Media personnel should bring their own food. Only broadcast microwave and satellite vans and their support personnel providing “live feeds” will be permitted in a parking lot adjacent to the In-Service Training (IST) building.

"California Executes Confessed Murderer," by Rone Tempest. (January 19, 2005)

SAN QUENTIN — Last-minute court appeals rejected and clemency vigorously denied by the governor, Donald Beardslee was executed early this morning, 24 years after he confessed to the slayings of two Bay Area women. As about 300 opponents of the death penalty held a vigil outside the prison, Beardslee, 61, was strapped to a gurney and injected with a fatal cocktail of drugs.

In an extraordinarily detailed statement Tuesday, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger said: "Nothing in his petition or the record of his case convinces me that he did not understand the gravity of his actions or that these heinous murders were wrong." Shortly after the governor's rejection, the U.S. Supreme Court without comment denied Beardslee's application for a stay. The decisions cleared the way for Beardslee's execution at 12:01 this morning, the state's 11th execution since voters reinstated the death penalty in 1978 and the first under the Schwarzenegger administration.

Beardslee refused a special final meal and had regular prison fare of chili macaroni, salad and cake. Among those gathered to witness the execution on San Quentin's death row were four family members of Patty Geddling, 23, and Stacey Benjamin, 19, whom Beardslee admitted killing and dumping in secluded spots after a dispute over a $185 drug deal in Redwood City, Calif.

At a state clemency hearing in Sacramento on Friday, defense attorneys asked Schwarzenegger for mercy in the case, saying that Beardslee suffered from previously undetected brain damage that caused him to commit the two 1981 murders as well as the fatal stabbing of a Missouri woman in 1969 for which he served seven years in prison. Hoping that Schwarzenegger would take a cue from the late Ronald Reagan, the last California governor to grant clemency to a condemned man, the attorneys asked that Beardslee be allowed to undergo a sophisticated magnetic resonance imaging brain scan not used during his trial. In a 1967 case, Reagan commuted the death sentence of a brain-damaged convicted killer because the latest scientific test, the 16-channel encephalograph, had not been available at the time of trial. But Schwarzenegger rejected the brain damage theory, noting that Beardslee functions at a very high level, earning "A's, Bs and Cs when he attended the College of San Mateo while he was on parole for the Missouri murder." After spending the weekend reviewing the case and the sealed recommendation of the state Board of Prison Terms, Schwarzenegger denied clemency for Beardslee, just as he did last year in the only other death case he has faced since taking office.

Last February, Schwarzenegger ignored appeals from a prominent chorus of American and international voices — including some in the movie business — and rejected clemency for escaped convict Kevin Cooper. Cooper was sentenced to death for the 1983 hacking deaths of three Chino Hills family members and a neighborhood friend during his flight from prison. Cooper was later spared from execution by the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, which sent the case back to lower courts to consider new DNA tests.

Because of the relative leniency he has demonstrated in parole cases — particularly compared with his Democratic predecessor Gray Davis — Schwarzenegger's early dealings in capital cases are being watched closely by the state's prosecutors and defense lawyers. In interviews, Schwarzenegger said he believes in the death penalty as "a necessary and effective deterrent to capital crimes." However, Legal Affairs Secretary Peter Siggins said in a February interview that the governor has indicated he would grant clemency if the right case came along. "He's certainly indicated that in the right case he'd be willing to entertain" clemency, said Siggins, who added: "I can tell you the governor is a supporter of the death penalty and believes it's an appropriate form of punishment." Since taking office in November 2003, Schwarzenegger has granted three pardons and issued the first commutation of a prison term by a California governor since Jerry Brown.

California leads the nation with 640 inmates on death row, but ranks 18th in executions performed since 1976. Texas ranks first in executions with 337, and second in inmates on death row, with 455 sentenced to death. Because of the complicated appeals process, condemned California prisoners wait an average of more than 20 years between the date of sentencing and execution. In fact, most inmates on the state's death row die of natural causes. Next in line for execution after Beardslee is Blufford Hayes Jr., whose 1980 death sentence is under appeal.

In the nearly quarter-century that he waited in San Mateo County Jail and on San Quentin's death row, Beardslee is reported to have become a model prisoner. According to testimony read at Friday's clemency hearing, he even assisted corrections officials on prison security. Former San Quentin Warden Daniel Vasquez described Beardslee as a rare inmate with no discipline record. "Killing him would be a shame," Vasquez said. But Schwarzenegger was not swayed by the good behavior argument. "I expect no less," he said.

The last-minute call for mercy was also countered by emotional testimony from the families of the two Bay Area women, including Geddling's grown children. "I don't know what problem [Beardslee] has with women. He seems to like to kill them," said Tom Amundson, Benjamin's older stepbrother.

In 1969, when he was 26, Beardslee killed a 52-year-old woman he met in a St. Louis bar, stabbing her in the throat with a knife and leaving her in a bathtub to bleed to death. After serving seven years of an 18-year sentence in that killing, the former Air Force mechanic moved to California to be near his mother. While on parole, Beardslee got a job as a machinist for Hewlett-Packard, where he got consistently good job evaluations.

In 1981, Beardslee picked up a hitchhiker, Rickie Soria, a drug addict and prostitute. Moving in with Beardslee, Soria introduced him to her friends. One of them, 19-year-old Bill Forrester, claimed that he had been ripped off in a $185 drug deal involving Geddling and Benjamin. Frank Rutherford, a drug dealer portrayed as the group's ringleader, devised a scheme to entice Geddling and Benjamin to Beardslee's apartment on April 24, 1981. The day before, Beardslee sent Soria to buy duct tape to tie the women's hands when they arrived.

After Rutherford accidentally wounded Geddling, Beardslee, Soria and Forrester drove her to a remote site in San Mateo County, where Beardslee shot the young mother twice in the head with a sawed-off shotgun. The next day, Beardslee, Soria and Rutherford, who had remained with Benjamin, used cocaine as they drove the Pacifica native 100 miles to a secluded area in Lake County, north of San Francisco. After the two men failed to strangle Benjamin with a wire garrote, Beardslee slit her throat with Rutherford's knife. Before leaving the body, the two men pulled down Benjamin's pants to make it appear that she had been raped. Police tracked down Beardslee using a phone number found at one of the crime scenes. As he had in St. Louis, Beardslee quickly confessed to the crimes and was the lead witness in the trials. Rutherford, who died in prison two years ago, and Soria were given long prison terms, and Forrester was acquitted.

Tried last, Beardslee was convicted and, after extensive jury deliberations, sentenced to die in San Quentin's gas chamber. The method of execution in California was later changed to death by lethal injection.

"California executes man who killed two women over drug deal," David Kravets. (AP 2:31 a.m. January 19, 2005)

SAN QUENTIN – With relatives of his victims watching intently, Donald Beardslee was executed by lethal injection Wednesday nearly a quarter-century after murdering two women over a drug deal. Beardslee was declared dead by San Quentin State Prison officials at 12:29 a.m., becoming the first California inmate put to death since 2002 and the 11th since the state resumed executions in 1992.

Thirty government officials, relatives of victims and media members, separated by a glass partition, watched the execution. It took nearly 20 minutes for officials, wearing medical gloves with their name badges removed to conceal their identity, to get the needles into Beardslee, who was tightly strapped to what looked like a dentist's chair. He was injected with a sedative, a paralyzing agent and finally a dose of poison to stop his heart – a process that took less than 10 minutes before Beardslee drew his final breath. Beardslee, who was wearing dark blue trousers, a light blue shirt, white socks and his eyeglasses, yawned about a minute after the first injection, then puckered his lips and did not appear to make any more movements, other than some heavy breathing. Moments later, Beardslee was pronounced dead. Officials said Beardslee did not make a final statement.

Outside the prison compound, about 25 miles north of San Francisco, about 300 protesters stood vigil, decrying the execution as state-sanctioned murder. Protesters carried candles and signs that said "Don't Kill In Our Name" and "Stop State Murder." One death penalty supporter carried a sign reading "Bye Bye Beardslee." Through an attorney, Beardslee told the protesters "that he wanted known his appreciation for these people's presence," actor and anti-death penalty activist Mike Farrell said, adding that Beardslee "even sent his regards to the people who put the staples in the signs." Steven Lubliner, one of Beardslee's attorney's said killing his client "accomplishes nothing. It demeans everyone."

Beardslee remained optimistic that he would be spared for the 1981 twin killings until Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger rejected a clemency petition seeking to commute the death sentence to life without parole, and the Supreme Court rejected two last-minute appeals Tuesday. "He was very talkative, smiling ... he still had a great deal of hope," said prison spokesman Vernell Crittendon. After his appeals were exhausted, Beardslee was "somewhat changed in his demeanor."

Beardslee, 61, chose not to have any of his family members witness the execution and has not had a family visit for at least the past month, since the formal countdown to the execution began, prison officials said. The condemned man spent his final hours in a special holding cell, where he was able to watch television, read and talk to his spiritual adviser. Warden Jill Brown said he brought his personal Bible to that room. He did not request a special final meal. Beardslee's lawyers claimed he suffered from brain maladies when he killed Stacey Benjamin, 19, and Patty Geddling, 23, to avenge a soured $185 drug deal.

His two appeals before the Supreme Court included claims that the lethal injection constitutes cruel-and-unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment, and that jurors were unfairly influenced when they rendered the death verdict. The court denied his appeals without comment.

Prosecutors have said Beardslee was not a passive, unwitting dupe when he committed the murders, as his lawyers claimed. They claimed Beardslee helped with the murder plot and sent his roommate to get duct tape to bind the victims before they even arrived at his apartment. "We are not dealing here with a man who is so generally affected by his impairment that he cannot tell the difference between right and wrong," Schwarzenegger said. The governor also brushed aside a claim that Beardslee should be spared because he was the only one of the three people convicted in the murders who received a death sentence. The governor noted that Beardslee was the only one on parole at the time for another murder.

Beardslee, a machinist, served seven years in Missouri for murdering a woman whom he met at a St. Louis bar and killed the same evening. The governor later rejected a request for a 120-day delay of the execution sought by defense lawyers who wanted the time to reopen the case before a federal court.

The last execution in California came on Jan. 29, 2002, when Stephen Wayne Anderson was put to death for shooting an 81-year-old woman in 1980. He was convicted of breaking into the woman's home, shooting her in the face and then fixing himself a dish of noodles in her kitchen. A year ago, 2˝ months after he took office, Schwarzenegger denied clemency to Kevin Cooper, convicted in the hacking deaths of four people in 1983. Cooper later won a stay of execution from a federal appeals court.

Associated Press Writer Kim Curtis contributed to this report.

"A witness's account of Beardslee's execution," by Kevin Fagan. (Wednesday, January 19, 2005)

Donald Beardslee's execution at San Quentin Prison Wednesday morning was a struggle for dignity.

The five guards who labored 16 minutes to insert the lethal injection needles into his arms struggled for composure, their lips tightening as they undoubtedly realized this was taking twice as long as usual. The 30 witnesses gathered in the observation room to watch through the thick glass of the apple-green death chamber struggled to keep their cool as the minutes dragged on, shifting uncomfortably on their feet, crossing and uncrossing their arms. Nervous coughs were the only sounds breaking the tension. And there, being put to death before all of us, the 61-year-old Beardslee seemed to struggle -- ever so slightly.

Once, as the triple-murderer was being led into the death chamber at 11:58 p.m. Tuesday by five prison guards, a look of concern or possibly worry flickered across his face. It was quickly replaced by a flatness of expression -- and when he was strapped by his ankles, chest and arms to the hospital-style gurney, he closed his eyes and lay so still he seemed asleep. He never moved while the prison guards hunted for the right openings in his flesh from midnight to 12:16 a.m. Wednesday. But after the intravenous lines were finally taped to each arm and he was left alone to await the poisons that would end his life, he let his emotions leak one more time.

Beardslee's chest heaved two quick sighs at 12:18 a.m. -- the same minute unseen hands from behind the death chamber walls began to send chemicals through the plastic tubes toward his body -- as if to say, "OK, let's get on with it." Beardslee's eyelids then fluttered open a brief moment, and two minutes later he yawned and smacked his lips twice. But from then on, the execution went just as it has for the previous nine lethal injections since 1996: His face turned from red to a deep, grayish blue, the breathing gradually stopped, and he didn't seem to twitch a muscle. At 12:29 it was over. That was one minute shorter than it took in 2002 for the last man put to death at San Quentin by lethal injection, Stephen Wayne Anderson -- but about double the execution time for most of the others. For those of us who watched, meanwhile, the minutes crawled by with no way to tell when they would end.

There were 17 other witnesses -- in addition to the 13 of us from the press -- in the stuffy, sterile-smelling observation room Wednesday, and from one end of the room to the other the tension seemed to build like a dark cloud. Nobody said a word; they werenâ't allowed to. But their actions betrayed them. Along the far wall from us, a woman in a red coat kept her arms folded tightly to her chest, uncrossing them just once when she clasped her hands before her face, as if in prayer. Next to her, a woman in frizzy black hair bit her lip, folded her arms too, and then unfolded them to clench her hands tightly at her waist. Halfway through the execution she fiercely pressed a knuckle into her mouth. At the end, after a prison guard announced that Beardslee had died and we from the media were being led out, the woman in frizzy black hair suddenly doubled over, fists at her mouth, gasping.

It was all done in near-utter silence, broken only occasionally by a nervous cough -- and one strange anomaly, one minute before Beardslee was pronounced dead. That's when Daily Journal reporter Michelle Durand fainted a little to my right from a combination of the stuffy heat and hunger. "That's the last time I forget to eat again after breakfast," she said sheepishly outside after she'd recovered and was gamely heading off to file her story. The whole affair, Durand's fainting notwhithstanding, was typical for the five San Quentin executions I have now witnessed -- the only exceptions being the gassing of David Mason in 1993, when reporters were allowed to call out what they saw as he convulsed in the chair, and the prison's first lethal injection in 1996. During that execution, the mothers of some of the 14 boys "Freeway Killer" William Bonin had raped and murdered sighed heavily, chests heaving, as they watched their sons' killer die.

This time, the death toll of the murderer before us was far smaller than Bonin's. But that, of course, did not mean the pain was any less for those touched by his evil. Beardslee throttled and slashed 19-year Stacey Benjamin and shotgunned her friend, 23-year-old Patty Geddling, in 1981 after they were lured to his Redwood City apartment in a beef over a drug debt. Twenty-four years later, the anger was stronger than ever for Benjaminâ's brother, T.Tom Amundsen -- and the rage radiated as he sat at the railing of the death chamber Wednesday. Amundsen, a Marine gunnery sergeant who tells of killing enemy soldiers in the Vietnam War, was stiff as a board while he watched his sister's killer breathe his last. He kept his eyes focused, laserlike, on the dying man -- and only once did he turn his head, for a quick nod to the media witnesses as they walked out the door. "I saw what I wanted to see. I'm glad," he told me shortly after the execution. "He was awful. He deserved to die."

Lying there on the gurney in his short-sleeved blue shirt and blue cotton pants, Beardslee didn't look like a killer. But then, they never do. Decades of near-solitary confinement in prison softens men like Beardslee, turning their complexions pasty from too much time inside and giving them a decorum they lacked when they went behind bars. Back when Beardslee was caught by police, he had a wild lion's mane of black hair, a thick beard, and eyes that stared into the camera for his jail mugshot with scary rage. The man I saw Wednesday had neatly cropped black hair, slicked back and turning gray at the temples, and a groomed gray mustache. Under his silver, wire-framed glasses, he looked more like a schoolteacher than a monster who killed two women, plus another woman before them, in Missouri.

Maybe that is reading too much into a cosmetic appearance. But the final moments of a man's life are telling, no matter how or where they come. And in a San Quentin lethal injection, there isn't much to go on -- just those few moments of watching guards struggle to insert needles, victim's survivors struggle to keep their emotions from erupting, and the killer himself try to stay composed as he dies in a very public way. By that measure, regardless of whether they approved or disapproved of the death penalty, Donald Beardslee and the people who came to view his final moments Wednesday managed to pull off their grim little event in the best way they could hope for: With dignity.

"Murderer Beardslee executed by lethal injection at San Quentin after governor, high court deny final appeals," Bob Egelko, Peter Fimrite, Kevin Fagan. (Wednesday, January 19, 2005)

Condemned murderer Donald Beardslee, who killed two young Peninsula women in 1981 while on parole from an earlier murder conviction, was executed by lethal injection early today at San Quentin State Prison.

Beardslee spent the last hours before his execution talking with his spiritual adviser and members of his legal team. He skipped the traditional last meal and only drank grapefruit juice before his death. No members of Beardslee's family were present for the execution, and the sole person who attended on his behalf was his attorney, Jeannie Sternberg.

Beardslee, of Redwood City, was convicted of the shotgun killing of Patty Geddling, 23, and the throat-slashing murder of Stacey Benjamin, 19. Prosecutors said the women were killed in revenge for a $185 drug debt claimed by another man.

T. Tom Amundsen, Stacey Benjamin's brother, and two of her cousins, Mark and Bobby Brooke, were present for Beardslee's death. None of Geddling's family members attended. Mary Geddling, who is married to Patty Geddling's son, Ivan, said: "I'm not going to stay up and watch it. .. . It's very hard on all of us." Corrections Department spokeswoman Terry Thornton said Beardslee had not had a visit from relatives in a month, although his brother and sister appeared before a state board last week to argue for clemency.

Beardslee declined to order a last meal and, at 7:42 p.m., refused the dinner provided to other prisoners of chili macaroni, mixed vegetables and green salad, said Todd Slosek, another spokesman for the Corrections Department. Slosek said Beardslee "seemed to be in good spirits." "He has been laughing and joking around with his legal team and his spiritual adviser," Slosek said. Around 6 p.m., prison officials escorted him to the death-watch cell in the prison, where he passed the evening with his spiritual adviser Margaret Harrell. His mood became more somber after the transfer. "He has gotten a little apprehensive, as anyone would who is facing death, " Slosek said.

Beardslee's fate was sealed Tuesday afternoon when Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger denied clemency and the U.S. Supreme Court denied review of his last two appeals -- one challenging the jury instructions at Beardslee's trial, the other claiming flaws in California's procedures for lethal injection. Later, Schwarzenegger rejected a defense lawyer's request to delay the execution for 120 days so that courts could further examine the lethal injection procedures after a federal appeals panel expressed qualms last week.

In asking Schwarzenegger to commute the sentence to life without parole, Beardslee's lawyers said a new report by a prominent neuropsychologist concluded that the 61-year-old inmate had been brain-damaged since birth. The report said the condition was worsened by two head injuries he suffered as a young man that left him unable to make independent judgments under stress.

But Schwarzenegger said Beardslee's apparent mental impairment did not prevent him from helping to plan the killings, acting purposefully during the crimes and trying to cover them up. The governor cited evidence that Beardslee told an accomplice to buy tape to bind the victims, helped to wipe down a van to remove fingerprints and, along with another man, pulled down one victim's pants to make the crime look like a sexual assault. "These actions show Beardslee's consciousness of guilt and the nature and consequences of the murders he committed,'' Schwarzenegger wrote. "There is no question in my mind that at the time Beardslee committed the murders he knew what he was doing -- and he knew it was wrong.''

Schwarzenegger also said Beardslee's record as a model prisoner for 20 years and the fact that he was the only participant in the crimes to be sentenced to death did not justify clemency. Beardslee was the only defendant with a previous murder conviction and the only one "who administered the coup de grace to each of the murdered women,'' Schwarzenegger said.

Ten prisoners have been put to death since the state resumed executions in 1992 after a 25-year hiatus. The last was in January 2002, when Stephen Wayne Anderson was executed for murdering a San Bernardino County woman during a 1980 burglary. California has 639 condemned prisoners, more than any other state. Beardslee confessed to each of his three murders, all committed against women he barely knew.

A native of St. Louis, he had no violent crimes on his record until he killed Laura Griffin, 54, in her apartment in December 1969, the same night the two met at a St. Louis-area bar. She was stabbed, choked and drowned in a bathtub. Beardslee, who described the killing to authorities as senseless and without motive, pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was sentenced to 18 years in prison. He was paroled in 1977 to the Bay Area, where his mother lived, and settled in Redwood City. He was still on parole, and working as a machinist at Hewlett-Packard, when he murdered Geddling and Benjamin in April 1981.

Witnesses said the two women were lured to Beardslee's apartment by Rickie Soria, a young woman who shared the apartment, in a scheme by a drug dealer named Frank Rutherford to take revenge for an unpaid $185 drug debt claimed by an associate, Bill Forrester. Rutherford shot Geddling in the shoulder. Beardslee was part of a group that then left with Geddling on the pretext of taking her to a hospital. They drove to a remote area near Pescadero where, according to prosecution testimony, Forrester shot Geddling twice, then gave the gun to Beardslee, who fired the fatal shots.

Beardslee and Soria returned to Redwood City, where Rutherford was holding Benjamin captive, and drove with her to Lake County. There, Rutherford tried to strangle Benjamin with a wire, Beardslee joined in, and then Beardslee got a knife and slit her throat. Linked to the crimes by a phone number on a piece of paper found near Geddling's corpse, Beardslee admitted his role to police, led them to Benjamin's body and testified against the other defendants. Rutherford was convicted of Benjamin's murder and sentenced to life in prison. He died in prison two years ago. Soria, who was on the scene of both murders, pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and is still in prison. Forrester, who denied shooting Geddling, was acquitted.

Beardslee was sentenced to death for Geddling's murder and to life without parole for Benjamin's murder. His appeals challenged the prosecution's use of the Missouri murder -- in which police may have questioned him illegally -- to argue for the death penalty; questioned the competence of one of his Redwood City trial lawyers, who read Bon Appetit magazine during part of Beardslee's testimony; and claimed his death sentence was disproportionate to the punishment of others who allegedly orchestrated Geddling's and Benjamin's murders. Over two decades, each claim was rejected by state and federal courts.

His final appeal of his death sentence, denied Tuesday, argued that penalty-phase jurors were prejudiced when the judge told them that Beardslee had been convicted of killing the two women to eliminate them as witnesses. The witness-killing charges eventually were overturned, but courts ruled that they did not influence the death verdict. In the other appeal rejected by the Supreme Court, Beardslee's attorneys argued that the state's procedures for lethal injection constitute cruel and unusual punishment and violate the condemned man's freedom of speech. If administered improperly, they argued, the chemicals could cause an agonizing death, and Beardslee would be unable to cry out because one of the drugs causes paralysis.

After the early-afternoon court rejection, one of Beardslee's lawyers asked Schwarzenegger for a 120-day reprieve to allow the courts to reach a final resolution on whether the state takes adequate safeguards in administering lethal injections. The attorney, Steven Lubliner, noted that the federal appeals court that refused to block the execution last week said it was nonetheless troubled by reports of possible problems in past executions and by the state's refusal to explain the need for the paralyzing chemical. But at 4 p.m., Schwarzenegger denied the reprieve.

San Quentin executions

Donald Beardslee, 61, became the 11th person to die in the San Quentin death chamber since executions resumed in 1992. The others:

April 21, 1992: Robert Alton Harris, 39.

Aug. 24, 1993: David Edwin Mason, 36.

Feb. 23, 1996: William George Bonin, 49.

May 3, 1996: Keith Daniel Williams, 48.

July 14, 1998: Thomas Martin Thompson, 43.

Feb. 9, 1999: Jaturun "Jay" Siripongs, 43.

May 4, 1999: Manuel Babbitt, 50.

March 15, 2000: Darrell "Young Elk" Rich, 45.

March 27, 2001: Robert Lee Massie, 59.

Jan. 29, 2002: Stephen Wayne Anderson, 48.

"Double Murderer Beardslee Executed in California." (Associated Press Wednesday, January 19, 2005)

SAN QUENTIN, Calif. — Prison officials executed a three-time murderer early Wednesday, making him the 11th inmate put to death in California since capital punishment was reinstated in 1977. Donald Beardslee, 61, was executed by injection for killing two women in 1981 while on parole for a third slaying. Officials said Beardslee did not make a final statement.

The execution came only hours after Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger rejected a clemency petition seeking to commute the death sentence to life without parole, and the Supreme Court rejected two last-minute appeals.

Beardslee's lawyers claimed he suffered from brain maladies when he killed Stacey Benjamin, 19, and Patty Geddling, 23, to avenge a soured $185 drug deal. His appeals before the Supreme Court included claims that lethal injection constitutes cruel-and-unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment (search), and that jurors were unfairly influenced when they rendered the death verdict. The court denied his appeals without comment.

The governor also rejected a request for a 120-day delay of the execution sought by defense lawyers who wanted the time to reopen the case before a federal court. "Nothing in his petition or the record of his case convinces me that he did not understand the gravity of his actions or that these heinous murders were wrong," Schwarzenegger said in a statement. "I do not believe the evidence presented warrants the exercise of clemency in this case."

Prosecutors brushed aside defense arguments that Beardslee was an unwitting dupe during the killings, claiming he helped with the murder plot and sent his roommate to get duct tape to bind the victims before they even arrived at his apartment. "We are not dealing here with a man who is so generally affected by his impairment that he cannot tell the difference between right and wrong," Schwarzenegger said. The governor also dismissed the contention that Beardslee should be spared because he was the only one of the three people convicted in the murders who received a death sentence. The governor noted that Beardslee was the only one on parole at the time for another murder.

Beardslee, a machinist, served seven years in Missouri for murdering a woman whom he met at a St. Louis bar and killed the same evening. After being released, he killed Benjamin and Geddling.

Beardslee chose not to have any of his family members witness the execution and hadn't had a family visit for at least the past month. He turned down a last meal, only drinking some grapefruit juice. Outside the prison compound, about 25 miles north of San Francisco, some 300 protesters stood vigil. Protesters carried candles and signs that said "Don't Kill In Our Name" and "Stop State Murder." One death penalty supporter carried a sign reading "Bye Bye Beardslee." Activists opposed to capital punishment also staged a small demonstration outside the U.S. Embassy in Austria to protest Austrian-born Schwarzenegger's decision. About a half-dozen protesters stood in the snow holding signs that read, "Schwarzenegger Terminates in Real Life," "Death PenaltyState Murder" and "No to the Death Penalty."

The previous execution in California was that of Stephen Anderson in 2002, who murdered an elderly woman in 1980. More than 600 men are on the state's death row. No California governor has granted clemency to a condemned murderer since then-Gov. Ronald Reagan spared the life of a severely brain-damaged killer in 1967.

"California Executes First Inmate in Three Years," by Adam Tanner. (Wed Jan 19, 2005 04:25 AM ET)

SAN QUENTIN, Calif. (Reuters) - California prison officials put three-time murderer Donald Beardslee to death on Wednesday, in the first execution in the state in three years.

Hours after Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger rejected a clemency appeal and cited Beardslee's "grisly and senseless killings," the warden at San Quentin State Prison north of San Francisco gave the midnight order to proceed. Five guards strapped a passive Beardslee to a table to administer lethal injections of three different chemicals, including potassium chloride, which causes cardiac arrest. The guards, working in a small room with five windows built as a gas chamber, took about 15 minutes to insert intravenous tubes into each arm. Once the drugs started flowing Beardslee let out a big yawn, blinked his eyes several times and moved his head before his breathing stopped shortly thereafter.

He spent his last day with his legal team and a female spiritual advisor, prisoner officials said, and did not prepare a final statement. He carried his personal bible to a waiting area before entering the death chamber. Earlier, Beardslee, 61, declined the state's offer of a special last meal of his choice, a prison official said. So he was offered the same meal as other inmates of chili, macaroni, mixed vegetables, salad and cake -- which he declined. He did ask for grapefruit juice however, a prison spokesman said.

After several minutes in which Beardslee was motionless, a note was passed through a hole in the death chamber and the prisoner was pronounced dead at 12:29 a.m. PST (3:29 a.m. EST) on Wednesday, executed for killing two women in 1981.

Four relatives of the victims attended the rare California execution but none of Beardslee's family were present.

Beardslee's attorneys had argued he was duped by accomplices and was suffering from mental illness aggravated by brain injuries when he shot Stacey Benjamin, 19, and choked and slashed the throat of Patty Geddling, 23, in California. The Air Force veteran, who was out on parole at the time for a 1969 murder of a young woman in Missouri, confessed to both killings and was sentenced to death in 1984.

"The state and federal courts have affirmed his conviction and death sentence, and nothing in his petition or the record of his case convinces me that he did not understand the gravity of his actions or that these heinous murders were wrong," Schwarzenegger said in a statement on Tuesday. Beardslee's attorneys had asked the governor to commute his sentence to life in prison without parole. In a detailed five-page response, Schwarzenegger detailed the brutality of Beardslee's three killings, and rejected the argument that the killer was mentally impaired. "We are not dealing here with a man who is so generally affected by his impairment that he cannot tell the difference between right and wrong," Schwarzenegger said.

Also on Tuesday, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Beardslee's request for a stay of execution, turning down his appeal without any comment or recorded dissent.

California, the nation's most populous state, has the largest death row population in the United States and perhaps the world, but it rarely administers the ultimate punishment. Lengthy appeals typically last two decades before an inmate is executed. Beardslee was the 11th inmate executed since California restored the death penalty in 1978. He was one of 640 people on California's death row, the largest in the nation. Texas is second with 455.

Donald Beardslee, 61, was sentenced be put to death by injection on January 19, 2005 at San Quentin State Prison for the 1981 slayings of two women. More than two dozen public officials, members of the victims' families and members of the media were scheduled to witness the execution. Beardslee's appellate challenges before the U.S. Supreme Court were claims that the lethal injection is cruel and unusual punishment and that jurors were unfairly influenced when they rendered a death verdict. In his clemency petition, Beardslee's lawyers claimed he suffered from brain maladies when he killed Stacey Benjamin, 19, and Patty Geddling, 23. The two were lured to his Redwood City apartment to avenge a soured $185 drug deal. At a hearing Friday on Beardslee's request, Former San Quentin Warden Daniel Vasquez called for clemency, saying Beardslee had been a model inmate during his 21 years on death row and contributed to the safety of guards and other prisoners. But Tom Amundsen, victim Stacey Benjamin's brother, said, "Now it's time to say goodbye to Mr. Beardslee. That's what I want, that's what my family wants." Prosecutors have said that Beardslee was not an unwitting dupe when he committed the murders, as his lawyers say.

"Convicted Killer Executed in California." (AP January 19, 2005) SAN QUENTIN, Calif. — Prison officials executed a three-time murderer early Wednesday, making him the 11th inmate put to death in California since capital punishment was reinstated in 1977. Donald Beardslee, 61, was executed by injection for killing two women in 1981 while on parole for a third slaying. Officials said Beardslee did not make a final statement.

The execution came only hours after Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger rejected a clemency petition seeking to commute the death sentence to life without parole, and the Supreme Court rejected two last-minute appeals. Beardslee's lawyers claimed he suffered from brain maladies when he killed Stacey Benjamin, 19, and Patty Geddling, 23, to avenge a soured $185 drug deal. His appeals before the Supreme Court included claims that lethal injection constitutes cruel-and-unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment, and that jurors were unfairly influenced when they rendered the death verdict. The court denied his appeals without comment.

The governor also rejected a request for a 120-day delay of the execution sought by defense lawyers who wanted the time to reopen the case before a federal court. "Nothing in his petition or the record of his case convinces me that he did not understand the gravity of his actions or that these heinous murders were wrong," Schwarzenegger said in a statement. "I do not believe the evidence presented warrants the exercise of clemency in this case."

Prosecutors brushed aside defense arguments that Beardslee was an unwitting dupe during the killings, claiming he helped with the murder plot and sent his roommate to get duct tape to bind the victims before they even arrived at his apartment. "We are not dealing here with a man who is so generally affected by his impairment that he cannot tell the difference between right and wrong," Schwarzenegger said. The governor also dismissed the contention that Beardslee should be spared because he was the only one of the three people convicted in the murders who received a death sentence. The governor noted that Beardslee was the only one on parole at the time for another murder.

Beardslee, a machinist, served seven years in Missouri for murdering a woman whom he met at a St. Louis bar and killed the same evening. After being released, he killed Benjamin and Geddling.

Beardslee chose not to have any of his family members witness the execution and hadn't had a family visit for at least the past month. He turned down a last meal, only drinking some grapefruit juice. Outside the prison compound, about 25 miles north of San Francisco, some 300 protesters stood vigil. Protesters carried candles and signs that said "Don't Kill In Our Name" and "Stop State Murder." One death penalty supporter carried a sign reading "Bye Bye Beardslee." Activists opposed to capital punishment also staged a small demonstration outside the U.S. Embassy in Austria to protest Austrian-born Schwarzenegger's decision. About a half-dozen protesters stood in the snow holding signs that read, "Schwarzenegger Terminates in Real Life," "Death PenaltyState Murder" and "No to the Death Penalty."

The previous execution in California was that of Stephen Anderson in 2002, who murdered an elderly woman in 1980. More than 600 men are on the state's death row. No California governor has granted clemency to a condemned murderer since then-Gov. Ronald Reagan spared the life of a severely brain-damaged killer in 1967.

Associated Press writers Kim Curtis in San Quentin and William J. Kole in Vienna, Austria, contributed to this report.

National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

California - Donald Beardsley - January 19, 2005

The state of California is scheduled to execute Donald Beardslee Jan.19 for the 1981 murder of Patty Geddling and Stacy Benjamin in San Mateo County. Beardslee is so severely mentally impaired that one hemisphere of his brain is virtually inert; he was condemned for peripheral involvement in a crime for which the principal instigators received lesser sentences.

At the time of sentencing, the jury was unaware of the extent to which Beardlsee's actions were influenced by brain damage at birth and subsequent head trauma. Dr. Ruben Gur, Director of Neuropsychology and the Brain Behavior Laboratory in the Department of Psychiatry at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, recently assessed Beardslee. He concluded that Beardslee suffers from severe brain damage that has particularly affected the right hemisphere of his brain leaving it "virtually non-functioning." Dr. Gur determined Beardslee is "unable to correctly process and contextualize information", and "the impairment produced confusion and paranoia under most unfamiliar circumstances." He found that Beardslee struggled to moderate appropriate responses to "fight/flight" impulses, often causing bouts of confusion and panic.

This mental condition also left Beardslee with a restricted emotional range, causing him to appear indifferent and aloof at trial. Unaware of his condition, the jury misinterpreted his emotional disconnect as an indication that Beardslee was a cold and calculating killer.

The trial court refused jury requests to provide information about the punishments imposed on his co-defendants, leaving jurors unable to weigh the relative culpability of the various participants. Beardslee had a far lesser role in the crimes when compared to his co-defendants. There is no evidence that his participation was pre-meditated and he fully co-operated with law enforcement, immediately informing on the instigators.

In twenty years in the structured environment of prison, he has had no disciplinary violations and has been praised by San Quentin staff belying prosecution warnings that he would pose a continued threat to guards and inmates if not executed. He is said to be an asset to the prison community.

If the execution is carried out, Beardslee will be the 11th person put to death in California since the state resumed executions in 1992, and the first since Jan. 2002. Please contact Gov. Schwarzenegger immediately asking him to grant Mr. Beardslee clemency.

People v. Beardslee, 279 Cal.Rptr. 276 (Cal. Mar 25, 1991)

Defendant was convicted in the Superior Court, San Mateo County, No. C-10632, Robert D. Miller, J., of two first-degree murders, and was sentenced to death by a different jury. On automatic appeal, the Supreme Court, Arabian, J., held that: (1) defendant was not deprived of the defense that he did not intend to kill the victims because he honestly but mistakenly believed they were dead when he inflicted the fatal blows; (2) the instructions on principals, including aiders and abettors, were sufficient; (3) the court properly empaneled a second jury for the penalty phase pursuant to the pretrial stipulated arrangement to select separate juries for guilt and penalty phases; and (4) defendant's statements to California officials that he had earlier committed a murder in Missouri were admissible, despite defendant's earlier illegal confession to Missouri officials. Set aside in part, and affirmed in part. Mosk and Broussard, JJ., issued concurring and dissenting opinions.

ARABIAN, Associate Justice.

Defendant Donald Jay Beardslee was charged under the 1978 death penalty law with the first degree murders of Paula (Patty) Geddling and Stacy Benjamin under two special circumstances. A jury found defendant guilty of committing both murders with premeditation and deliberation (Pen.Code, §§ 187, 189; all section references are to that code unless otherwise indicated) and further determined that each murder was committed under two special circumstances: concurrent conviction of multiple murders (§ 190.2, subd. (a)(3)) and intentional killing for the purpose of preventing the victim from testifying as a witness to a separate crime (§ 190.2, subd. (a)(10)). Defendant also was found to have personally used a firearm in the murder of Patty Geddling (§§ 1203.06, subd. (a)(1), 12022.5) and a knife in the murder of Stacy Benjamin (§ 12022, subd. (b)).

A penalty trial was then held before a different jury, which determined that defendant should suffer the death penalty for the murder of Patty Geddling and life imprisonment without possibility of parole for the murder of Stacy Benjamin. (See §§ 190.3, 190.4, subd. (a).) The trial court denied defendant's motions to strike the special circumstances and to modify the penalty, and entered a judgment of death. (§ 190.4, subd. (e).) Defendant's appeal is automatic. (§ 1239, subd. (b).) We conclude that one of the multiple-murder and both witness-killing special circumstances must be set aside, and that the judgment otherwise be affirmed.

GUILT PHASE EVIDENCE

Patty Geddling, age 23, and Stacy Benjamin, age 19, were murdered at separate locations on April 25, 1981. At the time of their deaths, they were living together as close friends. Stacy sold drugs and had a reputation for "ripping people off." Patty on occasion also sold drugs.

Defendant, age 37, was then living in his studio apartment in Redwood City with Ricki Soria, whom he had met two months earlier while she was hitchhiking. Defendant wanted to help Soria stop using drugs and to separate her from Ed Geddling (Patty's estranged husband) and Frank Rutherford, who were drug dealers. Rutherford had a reputation for carrying guns and collecting drug debts, and had bragged that he would never go to jail because he or his brothers would take care of any witnesses. He was prosecuted separately for the present killings, and defendant's transcribed testimony at Rutherford's preliminary hearing comprised a principal part of the prosecution's guilt phase evidence against defendant.

On April 23, Soria told defendant that Stacy had cheated William Forrester in a drug deal. The next afternoon, defendant agreed with Soria and Rutherford to help Forrester get back at Stacy and Patty that evening in defendant's apartment. Forrester came to the apartment, and defendant picked up Rutherford, who had a shotgun. The four discussed plans for trapping victims. Rutherford cut a wire and twisted the ends around shotgun shells. At defendant's request, Soria went out and bought tape for gagging the victims. It was agreed that when the victims arrived, Soria would sit on the sofa, defendant would open the door, and Rutherford and Forrester would hide. Defendant testified he expected Rutherford and Forrester to "rough [the victims] up a little bit," tie and gag them, take their money and drugs, and leave.

The victims arrived around 6:30 p.m. As defendant opened the door and they approached Soria, defendant heard the shotgun fire. He then saw that Rutherford was holding the gun and that Patty was wounded in the left shoulder. Defendant took her into the bathroom and tried to stop her bleeding. Both victims' hands and feet were tied. Rutherford told Patty they would take her to the hospital, and repeated this statement in Stacy's presence while winking at defendant. Between 9 and 10 p.m., defendant and Forrester left and brought back Rutherford's car.

After a discussion with Rutherford about taking the victims somewhere in their own van, defendant believed the victims would be killed. But when Rutherford handed him some shotgun shells, defendant said, "I'm not going to do this." Forrester said, "Well, I guess I'm going to do it." Patty was loaded into the victims' van, which was driven away by Forrester with defendant as a passenger. Soria followed in defendant's car. Rutherford stayed behind with Stacy. Forrester drove south on Highway 1 and on to Bean Hollow Road, where they stopped. Patty got out of the van and began pleading for her life. Defendant loaded the gun for Forrester, who shot Patty twice. Defendant reloaded and also fired at her twice.

Leaving Patty's dead body in a ditch beside the road, they departed, Soria and Forrester in the van and defendant in his own car. When the van ran out of gas, the three wiped off their fingerprints and abandoned it. Defendant and Soria then dropped off Forrester and returned to defendant's apartment. While there, they received a telephone call from Rutherford, asking them to join him at the nearby apartment of his girlfriend, Dixie Davis. Arriving at Davis's apartment between 3 and 3:30 a.m., they found Stacy watching television. Out of Stacy's hearing, defendant told Rutherford that Forrester had "chickened out" and defendant had to finish the job. Rutherford said defendant should have killed Forrester; defendant replied that Soria had refused to give him more shells for that purpose. Then, in Stacy's presence, defendant and Rutherford had a conversation implying that Patty was in the hospital.

About 5 a.m., defendant, Rutherford, Soria, and Stacy left in defendant's car. They stopped at a service station where Stacy collected money she was owed for drugs, stopped in Pacifica where Soria obtained cocaine, and made two more stops to consume the cocaine before crossing the Golden Gate Bridge. They stopped to see Rutherford's brother in Sebastopol, where defendant heard Rutherford obtain advice from the brother on where to "drop off" Stacy. Defendant understood this to refer to killing Stacy and leaving her body somewhere.

They headed north on Highway 101 and turned onto a winding side road. Defendant was driving. Rutherford told Stacy they were going to Lakeport to obtain drugs. They stopped at a turnout. Stacy was upset, but Rutherford coaxed her out of the car, and all four walked up the hill. Soria and Rutherford went back to the car, and Stacy asked if defendant was supposed to strangle her then. He said, "No." When Soria returned with Rutherford, she told defendant in a low voice that Rutherford had "fixed up" the wire. Defendant and Soria walked further, where they could not see Rutherford and Stacy. Defendant heard some commotion, however, and Soria urged him to go help Rutherford.

Defendant found Rutherford sitting on Stacy, strangling her with his left hand. A broken wire lay under her neck. Rutherford called Stacy a "die hard bitch." Defendant saw Stacy give him a pleading look, and he punched her in the left temple, attempting unsuccessfully to knock her out. Defendant then held one end of a wire wrapped around Stacy's throat while Rutherford pulled on the other end. Rutherford took both ends of the wire, pulled it tight, and twisted it. The two men dragged Stacy to a more secluded area. Defendant asked for Rutherford's knife and used it to slit Stacy's throat twice. After she was dead, defendant, at Rutherford's suggestion, pulled down her pants to make it appear that she had been assaulted sexually. Late that afternoon, Rutherford, Soria, and defendant returned to the Davis apartment.

Early that morning, Patty's body was found by joggers. A shoe repair claim ticket, recovered from her clothing, bore defendant's telephone number. Accordingly, Detective Sergeant Robert Morse of the San Mateo County Sheriff's Office called on defendant, who agreed to come to the sheriff's office to give a statement. Morse began the interview by talking about the difference between a witness and a suspect, and then asked defendant if he were involved in the case. Defendant replied: "Well, Frank [Rutherford] shot her but I guess I'm involved because I shot her in the head twice myself. I was afraid." Defendant was advised of his Miranda rights and gave a detailed, taped statement about both killings. From defendant's directions, officers found Stacy's body near the Hopland Grade Road in Lake County, as well as numerous items of physical evidence at scattered locations in San Mateo County. A transcription of defendant's statement, as well as the tape itself, became a prosecution exhibit at the trial.

Defendant testified in his own behalf. His trial testimony, his prior testimony at the Rutherford preliminary hearing, and his taped statement were essentially consistent, except for differences in his versions of the fatal blows. At trial and in prior testimony at the preliminary hearing, defendant said that after Forrester fired twice at Patty, defendant felt her pulse and decided she was dead. Nonetheless, he retrieved the gun from Forrester and fired twice in the direction of her head but did not think he hit her. He did this out of fear that Rutherford would have him killed if he were only a witness and not a participant in Patty's death. In his taped statement, however, defendant said he thought Patty was still alive after the shots by Forrester, and shot directly at her to keep her from suffering.

The condition of Patty's remains seemed more consistent with the taped statement. When her body was found, about one-third of her head was missing. According to the doctor who performed an autopsy, there were multiple shotgun wounds. One, in her left shoulder, preceded the others by several hours. A wound in her chest and another in her back, which occurred about the same time, would not have been immediately fatal; she could have survived for several minutes. The head wound, however, was inflicted by a shot or shots fired at extremely close range and caused instant death.

Similarly, defendant testified at trial and at the preliminary hearing that when he slit Stacy's throat, he concluded she was already dead because there was only one exhalation of breath, and the blood from her jugular vein dribbled out rather than spurting. He conceded he had helped Rutherford pull the wire around her throat, but he considered himself only a "minor" participant in her death. In his taped statement, however, he said that when he asked Rutherford for the knife, Stacy was still alive and trying to gasp, and that when he slit her throat he was trying to "make it quick."

The pathologist who examined Stacy's body testified that the knife wound cut her left jugular vein and exposed her air passage but did not cut the carotid artery. From the presence of blood in her lungs, he concluded that she must have been still alive when her throat was cut. He said the blood loss was relatively slow, "not the kind of blood loss you get from an artery."

Defendant testified as follows: He agreed at the outset to help Rutherford because he did not want to stand up to him. He felt shaky about Rutherford's bringing the shotgun to his apartment, but thought it would only be used as a scare tactic. He suggested Soria procure the tape for gagging the victims because he wanted to minimize any noise emanating from the apartment. But later in the evening, after Rutherford had used the shotgun on Patty, defendant became involved in the plans to dispose of the women out of fear for his life. He participated in both killings because he was afraid that Rutherford would have him killed if he were only a witness rather than a participant.

* * * *

X. ADMISSIBILITY OF THE MISSOURI HOMICIDE

A. The Facts

As previously stated, the prosecution introduced, at the penalty phase, (1) evidence that Laura Griffin was the victim of a homicide in Missouri in December 1969 and (2) defendant's admissions at the Rutherford preliminary hearing that he had killed Griffin. This evidence was admitted to show an aggravating factor, "criminal activity by the defendant which involved the use or attempted use of force or violence." The prosecution introduced no evidence of any criminal proceedings against defendant for killing Griffin. The evidence of defendant's guilty plea to the second degree murder of Griffin, and of his imprisonment in Missouri and subsequent parole to California in 1977, was brought before the jury by the defense in response to the prosecution's evidence.

Before the penalty phase commenced, defendant sought unsuccessfully to prevent the jury from hearing any of the foregoing evidence. After return of the verdicts of guilt, he moved to exclude all references to the Missouri homicide, on the ground that his prior admissions, which were the only evidence relied on by the prosecution to connect him to that crime, resulted directly from violations of his constitutional rights. The following facts were presented through exhibits, testimony, and a stipulation at the hearing of the motion on October 26 and 28, 1983.

After being charged in Missouri with the murder of Griffin, defendant moved to suppress all his statements to the police as involuntary and illegally obtained, and all physical evidence obtained as a result of those statements. At the hearing on the motion in November 1970, the Missouri arresting officer testified that defendant had been surrendered by his counsel, who told the officer he did not want defendant to give the police any statements. The officer testified that after placing defendant in a psychiatric hospital, the officer visited defendant and questioned him about another crime, but did not talk to him or take any statement from him about the Griffin homicide. The officer said he learned of certain physical evidence in a trash can from defendant's friend, Sandy Columbo, before his visit to defendant. Defendant testified that soon after being placed in the hospital, he was interrogated by the officer about the killing of Griffin and gave the officer specific details about the crime and about physical evidence that might be found in a trash can near his house. The officer did not advise him of his right to counsel, and told him that his statements could not be used against him in court. Defendant told the officer he had divulged the details of the crime to Columbo, who had accompanied defendant and the police when he was taken to the hospital. He had told Columbo about the physical evidence in the trash can.

On November 19, 1970, the Missouri trial court denied defendant's motions to suppress. On December 8, defendant pleaded guilty to second degree murder and was sentenced to 19 years' imprisonment with credit for the nearly one year he had spent awaiting trial.

After defendant's confession to, and arrest for, the present murders in April 1981, his then counsel, Douglas Gray, made an agreement with the prosecutor, at defendant's instigation, that defendant would give a further statement and would testify at the trials of his codefendants, not in exchange for any reduction in penalty, but for assurances that best efforts would be made to ensure his physical safety in custody (since he would be viewed as a "snitch") and that his trial would follow those of the codefendants. Under informal questioning by the prosecutor in Gray's presence in January 1982--which was preceded by an admonition and waiver of the Miranda rights--defendant volunteered that he had told Rutherford about his conviction for murder in Missouri. Under questioning, he described how he had committed that crime. At the Rutherford preliminary hearing in January and February 1982, defendant testified to still further details of Griffin's murder. His last testimony in a codefendant's case was at the trial of Forrester in April 1982.

In late September 1982, investigators from the San Mateo County Sheriff's office went to Missouri to obtain further evidence of the murder of Griffin in 1969. They interviewed a number of witnesses including Sandy Columbo and the officer who had arrested defendant. The investigators reported that the arresting officer stated as follows: Upon surrendering defendant to the police, defendant's attorney, Donald Clooney, told the police not to talk to defendant. After Clooney left, the officer "conducted an interview" with defendant, who confessed to the murder and described physical evidence connecting him to the victim, and where such evidence could be found. Based on these statements, the officer obtained this evidence from a garbage can behind defendant's apartment. The officer said that during a suppression hearing in court, he "lied on the witness stand" about where and how he had obtained the evidence. Columbo had also told him where certain items of evidence had been found, and the officer testified that seizure of the evidence had been based on her statements.

One of the California investigators testified at the California suppression hearing that the arresting officer did not "specifically" say how he had lied at the Missouri hearing. Later, he testified the officer "told us that the attorney [for defendant] had told him not to speak with his client, question him. He waited for the attorney to leave and did so anyway." The investigator believed the officer also "somehow" lied on the witness stand regarding the recovery of the physical evidence implicating defendant. He did not "interrogate" the officer regarding the nature of the lies but instead "accepted his statement without specific context."

Upon receiving the investigators' report in October 1982, the prosecutor promptly delivered a copy of it to defendant's counsel, Gray. On December 1, 1982, the prosecutor held a lengthy telephone conversation with the Missouri officer. This time, the officer suggested that the incriminating conversation consisted of defendant "just volunteering" the information. The officer said that before he spoke with defendant, the Missouri police had no evidence linking defendant to the Griffin murder. The crucial physical evidence was obtained from a trash can in which defendant told the officer he had burned Griffin's purse. Laboratory tests of burned marks in the bottom of the can revealed Griffin's bank number. Columbo was present when defendant made his self-incriminating statements. Thereafter, the officer questioned Columbo, who said that defendant had told her what she heard him disclose directly. Thus, the evidence that the police planned to use to link defendant to the Griffin murder consisted of the physical evidence from the trash can and his admissions to Columbo. The prosecutor's detailed report of this conversation was promptly delivered to defendant's counsel.

In September 1983, counsel applied for a certificate for the attendance of out-of-state witnesses (§ 1334.3), with which the defense sought to subpoena two Missouri officers, including the one who had arrested and questioned defendant, as well as Columbo and Clooney, to testify at defendant's penalty trial in California. Counsel's declaration in support of the application stated that the witnesses were necessary to establish that defendant's confession to the Missouri police of the Griffin murder, and the physical evidence connecting defendant with that crime, were obtained as the result of an illegal interrogation. In opposition to the application, the California prosecutor declared to the Missouri court that he did not intend to introduce any evidence that defendant was convicted of the Missouri crime, or any statements made by defendant to Missouri officers, or any physical evidence obtained after the Missouri police learned that defendant was involved. He said he intended to introduce only testimony describing the scene of Griffin's death and the wounds disclosed by the autopsy, together with defendant's admissions of the crime to California sheriff's detectives and at the Rutherford preliminary hearing. The Missouri court denied the application, ruling that none of the requested witnesses' proposed testimony was necessary or material to defendant's trial.

Attached as exhibits to defendant's California motion to exclude all evidence of the Missouri crime were (1) transcripts of the Missouri proceedings in 1970 concerning defendant's unsuccessful motion to suppress evidence and his subsequent guilty plea, (2) excerpts from defendant's statements to California sheriff's detectives and his testimony at the Rutherford preliminary hearing, all in January 1982, in which defendant admitted killing Griffin, and (3) the reports of the California sheriff's investigation in Missouri in September 1982 and the prosecutor's follow-up telephone conversation in December 1982, which revealed the admissions of the Missouri officer of his perjury in the 1970 suppression proceeding. At the two-day hearing in October 1983, it was stipulated that these exhibits could be received as correct copies of what they purported to be and could be considered as evidence of the truth of their contents. It was further stipulated that (1) defendant's confession to the Missouri officer of the homicide of Griffin was obtained in violation of the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the United States Constitution, (2) the physical evidence of that crime (other than the body and the crime scene) was obtained as the direct unattenuated result of the unlawfully obtained confession, and (3) at the time of defendant's admissions of the Missouri murder in January 1982, neither defendant nor his attorney was aware of the grounds for vacating his Missouri conviction that were subsequently discovered by California investigators in September 1982 and by the prosecutor in December 1982. Attorney Gray, who was still representing defendant in early 1982, testified that if he had known then of the perjury of the Missouri officer in the 1970 suppression proceeding, he would have done whatever he could to prevent defendant from giving any further statements to the police or the prosecution, or from testifying in the proceedings against any of his codefendants. Gray also testified, however, that defendant "indicated really almost enthusiasm for assisting the prosecution." The prosecutor testified he believed the Missouri officer had committed perjury. In argument, he "concede[d] it's perjury." The motion to exclude all evidence of the Missouri homicide was then denied.

B. Discussion

Since defendant was not allowed to call as witnesses in the California hearing any of the Missouri officials, and the Missouri officer has admitted he lied on the witness stand, the record is not precise regarding what occurred in that state. The only evidence we have about the nature of the officer's lies is his conversations with the California authorities, who did not ask probing questions. Defendant does not and cannot complain of this circumstance because the prosecution stipulated to the crucial facts. The important facts for our analysis regarding the events in Missouri are that defendant's confession was obtained in violation of his Fifth and Sixth Amendment rights, that the physical evidence implicating defendant in the Griffin murder was obtained as the direct unattenuated result of the unlawfully obtained confession, and that the officer committed perjury at the suppression hearing.

The prosecution here did not seek to present evidence of the Missouri confession or of any of the incriminating physical evidence. Rather, it proved the corpus delicti of the murder--which is clearly not tainted by the illegal conduct--and defendant's 1982 statements in California admitting the murder. Thus, the sole issue before us is whether the California statements were rendered inadmissible because of the misconduct in Missouri. We conclude they were not.

* * * *

The excess multiple-murder special circumstance and both witness-killing special circumstances are set aside, and the judgment is otherwise affirmed.

Beardslee v. Woodford, 358 F.3d 560 (9th Cir. January 28, 2004)

Background: Following affirmance of his state-court conviction for murder with special circumstances and death sentence, 53 Cal.3d 68, 279 Cal.Rptr. 276, 806 P.2d 1311, petitioner sought federal habeas relief. The United States District Court for the Northern District of California, Saundra B. Armstrong, J., denied petition, and petitioner appealed.

Holdings: The Court of Appeals, Thomas, Circuit Judge, held that:

(1) although level of investigation conducted by petitioner's prior counsel fell below constitutionally acceptable standards, prior counsel's failure to investigate potential mitigation strategies did not actually prejudice petitioner;

(2) court's errors in failing to specifically address jury's question concerning instructions at petitioner's trial, and telling jury that "there is and can be no explanation of the instructions," in violation of petitioner's due process rights to fair trial were harmless;

(3) court's failure to instruct jury on lesser-included, non-capital offense of manslaughter at petitioner's trial pursuant to defense theory of imperfect duress did not leave jury with all-or-nothing choice in violation of due process;

(4) evidence that none of petitioner's codefendants had received death penalty was not relevant at sentencing phase; and

(5) prosecutor impermissibly penalized petitioner for his refusal to testify by calling attention to petitioner's failure to express remorse, but such error did not warrant federal habeas relief.

Affirmed.